Portrait of the US military base

in Cuba

CHAPTER 1

FRONTIER ZONE

By Yisell Rodríguez Milán

I am in Caimanera. Behind me, on one side of the long, semi-deserted highway is the biggest salt mine from Cuba and a “Restricted Access” sign that announces the entry to the town closest to the U.S. military base that the world calls Gitmo. Here they simply call it “The Base.”

“Your pass, please,” an official tells me at the entrance to the community, and I hold out the paper that states my date of arrival and exit, who I am and whom I am coming to see.

My friend’s husband is waiting for me. If he weren’t there I wouldn’t be able to enter. That’s what they tell me, although I already knew. Who doesn’t? In Guantanamo they teach you from childhood that in Caimanera no one gets in without a pass, that someone always has to meet you (unless you work there), and that it is a special area, so special that its inhabitants earn 30% extra on top of their salary, and receive extra benefits from butchers and warehouses. All this is explained by the danger, the proximity, the foreign militarization of a small fragment of the land.

I inspect the two main streets. One is called Correo (Post), where the seat of the Government and the media are, along with some self-employed individuals and a small central park. The other street is Carretera (Road). Going straight down it you can arrive at the edge of the sea, from where it’s possible to see, skirting the coast, the wreckage of some wooden houses, built on stilts and covered with sheets of zinc. They say that this is how they used to build houses in the South of the United States.

A friend once told me that living a few kilometres from the Base was as normal as living in Guantánamo city: “but you always fear the unexpected.” “You can see the 4th of July fireworks,” he said to me, “and you occasionally hear the sounds of the military training.”

A neighbour explained how the town works. The locals travel to the more isolated communities in dinghies and a small catamaran, while they go to the provincial capital on bus or train. She also, very kindly, shows me the way to the main museum where – she says – they will explain it all to me much more clearly.

Ofelia García Campusano, the museum director, talks to me about prostitution, which seems to be another historical trauma for Caimanera… after the Base. Until the middle of the 20th century, she said, in the southern part of the city there was a tolerated Red Light District, a neighbourhood full of bars and brothels like the “Cachalotte Bar.”

“The girls left the countryside and came to Caimanera to look for work. The men did the same because there were over 2,000 businesses of all kinds here, related to the port and the Base, but the women always had worse luck and ended up in the brothels. Once used, they couldn’t go back to their homes.”

This permissive zone was the first one that had a “health office” (a type of medical clinic), asphalt streets, and access to drinkable water. It even had Guidelines on practicing prostitution, a copy of which – Ofelia confirms – is held in the municipal archives.

“Caimanera became Cuba’s biggest brothel, and around 3,000 women of Guantanamo married American officials and sailors,” explains José Sánchez Guerra, the Historian of Guantanamo City, who claims that the business from traders and brothel owners linked to the Base reached 23 million dollars annually in the 1950s.

They say that from Boquerón, a community located to the side of the entry to the large bay that belongs to the “Martyrs of the Border” People’s Council, you can see everything more clearly… including the building’s infrastructure, the airports and the bay.

The town seems too quiet to me and claustrophobic, despite the squalls. In the queue for the bus I talk to a woman. I ask if she remembers the Chanel 8 programs, broadcast in English for the Marines, and she tells me “Yes, but you can’t pick up the signal for it anymore.” Sometimes you can still tune into a radio broadcast in English.

I arrive home. I turn on the computer to download the photos from the trip and I open the document where I saved the transcription of a debate hosted by Temas magazine in Havana, focusing on the Naval Base. The moderator argues that the Guantanamo Bay is 10 times bigger than the bay in Santiago de Cuba, 15 times bigger than Mariel and 24 times bigger than the Havana Bay. The surface area is comparable to that of Manhattan, and I, at this distance, can only think of the size of the bite that the Americans took out of us.

BALSEROS

1994 marked a new chapter in the Guantánamo story as a mass exodus of Cubans attempted to emigrate to the United States. Tens of thousands of Cuban rafters made the perilous voyage across the Florida Straits, often travelling aboard homemade rafts improvised out of truck inner tubes and wood. Many also chose to make it to the base, by both land and sea.

After a number of weeks and with the objecting of averting mass immigration to the United States, President Bill Clinton ordered the US coast guard to intercept all rafters at sea and transport them to Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. Over 30 000 Cubans were held at the high security naval base. The rafters concentration camps were a precursor to the infamous Guantánamo Bay prison camps we know today.

SOURCE:

Fragment of the documentary Balseros (Rafters) (2002) by Carles Bosch and Josep Maria Domènech i Graells / Courtesy of producers

In December 1994 the first group of elderly people, children and pregnant women left from the naval base heading to the United States. Throughout 1995 almost everyone who had been held at base was able to reach the United States.

Many Cubans, both inside and outside the island, have stories to tell about emigration and Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. If you have a story to tell, please get in touch!

CHAPTER 2

LA BASE

WELCOME TO PARADISE!

By Ed Augustin

The Big Mac’s always been my favourite. I like the way they’re all the same – the squishy bun, the tasteless gherkins, and the familiar shape of the burger. Wherever you are in the world, you can bet your bottom dollar that your Big Mac will be reassuringly, comfortingly the same. And that’s just as well when you’re in one of the world’s most infamous places: Guantanamo Bay.

McDonald’s isn’t the first thing one might associate with Cuba. The golden arches conjure up images of globalised capitalism and the spread of the American way of life; everything the Cuban revolution has defined itself against. Yet on the South Eastern tip of the island, along an arid road lined with cacti, lies Cuba’s only McDonald’s.

It’s 8:00am on Friday morning a few hundred metres from Camp 5 at the tail end of the shoot. A bit early for a burger, I know, but the Big Mac’s always been my go-to.

A friendly woman from the Naval Base’s Public Relations Unit is filling me in about how US ships first arrived in Guantánamo Bay over one hundred years ago. Around us a dozen or so Joint Task Force military personnel are tucking into more conventional breakfast-fare: bagels, crispy apple pies and Egg McMuffins.

Perhaps some were catching a bite to eat after a night shift guarding the prisoners. Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, identified by the 9/11 Commission Report as the “principal architect of the 9/11 attacks”, is one of the “high value detainees” held on site.

While gulping down the last of their coffee, perhaps other personnel were mentally preparing themselves for a morning session of force-feeding the prisoners. Most of the prisoners languishing in GTMO have never been put on trial or even been charged. This indefinite imprisonment has fuelled a wave of hunger strikes. During my visit, the majority of the complex’s 166 inmates were refusing to eat. With so much tension in the air, GTMO’s could-be-anywhere McDonald’s provides a welcome sense of normality.

McDonald’s is one of the many idiosyncrasies that GTMO throws up at visitors. The base, which is home to around 6000 US servicemen and women, has its own schools, churches, cinemas and even an American football field. With the prisoners and the watchtowers tucked safely away behind the hills, some neighbourhoods here resemble a 1950s U.S. suburb.

For Simon Johnston, the bases former public works officer, “It’s like an Eisenhower-era town: You can leave your door unlocked, no one uses bike locks, and you even have the Communist enemy to stare down.”

On my first day at the base I was invited to Camp 6 for a guided tour and an interview with some prison guards. While waiting to be frisked, I read a slogan under the GTMO logo: “Honor Bound to Defend Freedom”. I soon found out that this is Guantánamo Bay’s official motto!

Before arriving at Guantánamo Bay, ‘freedom’ wouldn’t have been the first word to come to mind. For 15 years now, the prison has been a weight on America’s moral conscience; a blemish that grates with the country’s self-image. Americans don’t like to think that their country kidnaps innocent civilians, tortures, or embraces lawlessness. Yet the Bush Administration chose to imprison those they suspected of terrorism in Guantánamo Bay precisely because the US constitution – and the legal protections it affords – does not apply there.

Most of the personnel I spoke to at the base, however, seemed to take the freedom theme seriously. In Camp 3 I was introduced to a group of medics who proudly demonstrated how “enteral feeding” (a.k.a. force-feeding) is carried out on “non-compliant detainees”. When I asked a nurse there how force-feeding squares with GTMO’s motto, he didn’t miss a beat: “Like it or not, our mission is to safeguard these detainees, keep them alive, keep them medically healthy, and that’s helping the global War on Terror… So, yes, we are honor bound to defend freedom. And we do that every day.”

SOURCE:

http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2014/12/09/here-is-the-cia-torture-report

The freedom leitmotif repeats itself in bizarre ways throughout the 45-square-mile base. Just outside the hotel I was staying stands a sign welcoming visitors with the word “Liberty”. It’s bold blue letters ensnared in barbed wire and – cherry on the icing – an iguana firing a machine gun perched on top!

A final quirk that many visitors come across at the base is the gift shop. Presumably intended for family and friends visiting loved ones posted at the base, rather than for prisoners to buy a memento on their way out.

I couldn’t resist going in. Guantanamo teddy bears, mugs and baseball caps lined the shelves. I bought a t-shirt reading “GTMO: Welcome to Paradise!”

It’s hard to find much reference to Cuba amongst the trinkets on offer. Like Big Macs, GTMO tourist paraphernalia has a habit of feeling tub-thumpingly American. Perhaps the historian Jonathan Hansen, author of the book Guantánamo: An American History, is right when he writes “in many ways, Guantánamo Bay remains more quintessentially American than America itself: a distillation of the idealism and arrogance that has characterized U.S. national identity and foreign policy from the very beginning”.

With the Cuban-US relationship in flux, and Raul Castro’s team ushering in big economic changes, perhaps the Golden Arches will adorn some unsuspecting street in Havana before too long. But for now Guantánamo Bay remains home to Communist Cuba’s one and only McDonalds.

US VIEWS ON GUANTÁNAMO: A PROBLEM OF PEDAGOGY?

By Bonnie A. Lucero

Mere months before the tragic attacks on the Twin Towers in September 2001, I was sitting in my ninth grade history class, hearing for the very first time about Cuba. My teacher recounted the triumphant story of the Spanish-American War of 1898, calling it as many North American today still do, a “Splendid Little War.”

I learned that the United States invaded the Caribbean island to liberate Cubans from Spanish tyranny, selflessly driving the flag of freedom deep into its soil. Our discussion of this transformative moment in the histories of the United States and Cuba did not so much as allude to one of the most powerful legacies of that military intervention: the imposition in 1901 of the sovereignty-limiting Platt Amendment upon the Cuban Constitution.

FUENTE:

Platt Amendment http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=55

While the Platt Amendment brought the United States’ military occupation (1899-1902)—the first of several to come—to an end, it also imposed a set of other limitations on Cuban sovereignty, including the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and an indefinite lease over territory in the eastern Cuban province of Guantánamo that would become, in 1903, the coaling station and naval base. How could we have missed such a significant piece of this story, and what political consequences does this pedagogical sleight of hand have for North American understandings of Cuba today?

It is my contention that the patriotic narratives we feed North American children in public schools constitute a major factor in shaping US sentiment regarding Guantánamo.

Recent opinion polls find that most US citizens oppose closing Guantánamo Bay. For example, in November 2009 when US president Barack Obama declared his intention to close the prison, just 39% of people polled approved of this decision. In contrast, 70% of people surveyed approved when Obama outlined a policy to keep the prison open in February 2012, according to one Pew Research Center Study. In 2013, a Huffington Post survey found that 54% of North Americans thought that the prison should remain in operation. A Gallup poll found that as recently as 2015, two-thirds of North Americans believe their government should keep the Guantánamo open, despite the recent declassification of Senate Select Committee on Intelligence reportrevealing the exploitation of the legal limbo of Guantánamo to perpetrate torture against detainees during the presidency of George W. Bush.

.

What is so interesting about these polls is that they show only minimal divergence in views of Guantánamo between Democrats and Republicans, despite their vehement opposition on so many other salient issues. Although Republicans are more adamant in their support for the persistence of the naval base, Democrats also support it in their majority.

One potential commonality between Democrats and Republicans is history curriculum. Despite historical research since the 1960s gradually exposing the limitations of romantic narratives of the Spanish-American War, much of the curriculum on this topic continues to focus on stories of North American heroism and benevolence toward Cuba.

For example, Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills for Social Studies requires high school students to “explain why significant events, policies, and individuals such as the Spanish-American War, U.S. expansionism, Henry Cabot Lodge, Alfred Thayer Mahan, Theodore Roosevelt, Sanford B. Dole, and missionaries moved the United States into the position of a world power” (emphasis mine).

Ultimately, what that curriculum standard is asking teachers to do is to frame the Spanish-American war not as a major moment in US imperialism, but rather in terms of the projection of American greatness.

Another aspect of the curriculum demands that Texas high school students “evaluate American expansionism, including acquisitions such as Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico” (my emphasis). By characterizing the forced annexation of these territories as “expansionism” rather than “imperialism,” this pedagogical standard pre-empts perspectives that critique this moment as potentially detrimental to the peoples of these colonies. Moreover, the omission of Cuba from the list of annexed territories silences a large corpus of debates and writings by prominent US citizens who desired to make permanent US control over Cuba. Texas social studies standards make no reference to the Platt Amendment or to Guantánamo. Nor is Texas alone; because of the size and influence of the state, Texas social studies standards tend to be enmeshed in history textbooks used across the country.

.

Caricatura: Osval

It should come as no surprise that US citizens who have received the kind of history education described above would opposed the closure of Guantánamo. Teaching the future citizens of the United States that their country “freed” the Cuban people by extension teaches them that the Cuban people have incurred some sort of “debt of gratitude.” Framing the invasion and annexation of foreign lands in terms of US greatness and world prominence instills in students the flawed idea that the violation of national sovereignty and the flagrant disregard for the will of the people are but minor causalities in the making of the greatest country on earth.

Rather than seeing Guantánamo as a legacy of the very imperialism most North Americans swear we never perpetrated, this curriculum teaches students—who will soon come of age as voters—that we are entitled to lease Cuban land indefinitely as payment for historic debts and as a tribute to North American global preeminence. If we taught North American school children to critically examine, rather than tacitly accept, these patriotic narratives of US history, then we might have more hope of challenging some of the persisting legacies of US imperialism.

* Bonnie A. Lucero, american professor of History in Texas-Rio Grande Valley University

CHAPTER 3

US MILITARY EXPANSION

A MILITARIZED WORLD

By Eliades Acosta

In 1890, few could have imagined that at a desk in the Newport Naval College, Rhode Island, a brilliant strategist named Alfred Thayer Mahan was redesigning the power dynamics of the world, with the aid of treaties about the Roman Empire, the French Revolution and the British Empire.

Mahan’s interest in unearthing the keys to Europe’s naval power and far reaching empires was seen by his contemporaries as nothing more than the innocent hobby of a U.S. historian, slightly obsessed with the issue. But then everybody understood that something miraculous had occurred at that desk after his masterpiece “The influence of sea power upon history,1660-1783” was published; a text which was to become the handbook of Theodore Roosevelt, deputy secretary of the U.S. Navy and future President, who together with the rest of the U.S. government, wished to rob the crumbling Spanish empire of its last possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific.

Mahan’s strategic and geopolitical theories were not the work of an over-productive imagination, or creative genius, but the cold analysis of a man who knew that in New York’s enormous steel industry and Chicago’s processing plants, in the growth of new colonies, the development of the railways, communications and westward expansion toward the Pacific, and in particular in the hands of the powerful northern bankers, a world with expansionist ambitions as great as those of Cesar’s Rome was being born, which in order to achieve would require overseas territories, trade routes, raw materials and markets like that of the British empire.

For Mahan’s prophecies – based on thorough historical research – to become true, U.S. presidents would have to guarantee five conditions: guarantee prosperous foreign trade; create an effective merchant shipping system; deploy strong naval units across the globe, able to protect trade routes and national interests; control colonial or semi-colonial territories able to supply cheap labor, raw materials and markets; and lastly establish a network of naval, fuel and military bases able to support the entire system, with the potential to provide speedy and adequate responses to any challenge or threat.

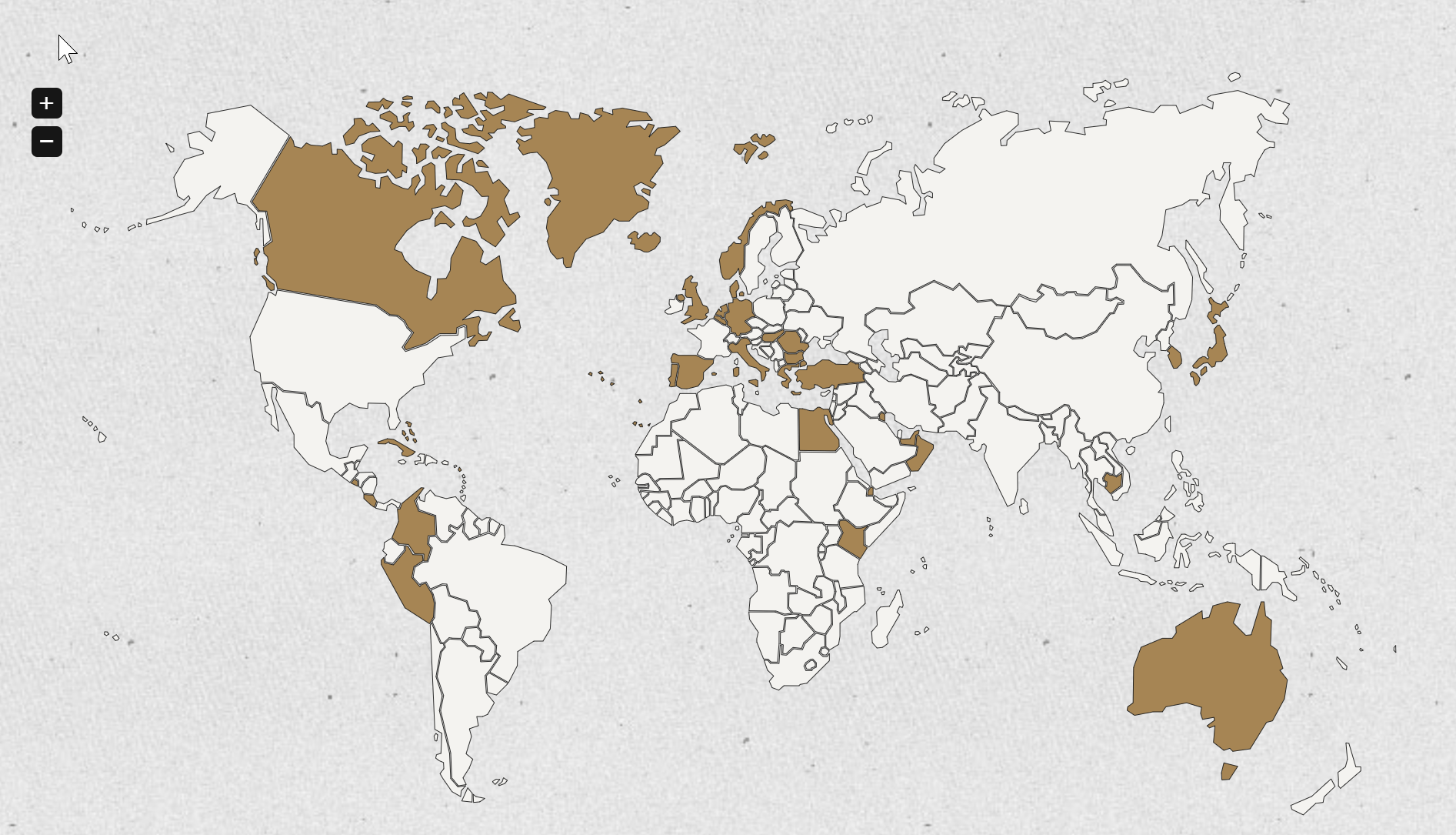

The limits of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s expansionist vision have been far exceeded. Today U.S. global power reaches dizzying extremes. A tally of all U.S. military bases around the world, reveals the most extraordinary map.

Using the language consistent with the age of political correctness in which we currently live, the U.S. government typically attempts to disguise this shocking reality, stating that its bases serve to ensure civilized coexistence between nations, guarantee the sovereignty of the peoples and act as response centers to deal with emergency situations in fragile nations such as Haiti, Pakistan and all the African countries.

The United States has the presence, be it in military bases or infrastructure in several countries. Here are some examples issued by the US government, although alternative sources estimate many more, including facilities throughout Latin America.

SOURCES:

[1] Military Installations (2016, Marzo 1) obtenido de: http://www.militaryinstallations.dod.mil

[2] Military Installations (2016, Marzo 1) obtenido de: http://www.acq.osd.mil

We live in a world of global military powers, none of which however, come close to the strength and size of the U.S.

According to the chaos theory, the flap of a butterfly’s wing can cause a tsunami on the other side of the world. Alfred Thayer Mahan’s visionary work goes some way to supporting this idea, given that for every page in his book, successive U.S. governments have opened two military bases on foreign soil.

Because of Homer, Helen of Troy has gone down in history as “the face that launched a thousand ships…”

A careless naval officer like Mahan, famous for causing various maritime mishaps, drew a chillingly accurate map of imperial power which today has reached all four corners of the globe.

And is still growing…

*Eliades Acosta, Cuban philosopher and essayist.

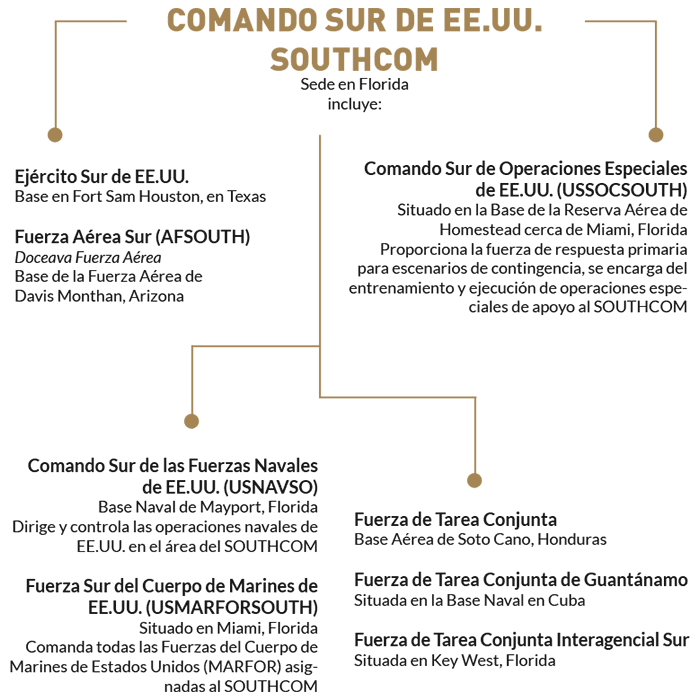

US MILITARY BASES IN LATIN AMERICA

By Francisco Domínguez

Notwithstanding Latin America’s progressive transformation of the last decade and a half, U.S. military might, continues to overshadow the region. The U.S. has about 47 military installations throughout the region, most of which cluster around the Caribbean, Central America, and especially the North West of South America, with Colombia and Panama ‘hosting’ 10 and 12 respectively.

To this must be added the recently re-established US Fourth Fleet, charged with patrolling the Caribbean, the South Atlantic, and all South America’s Pacific coast up to Guatemala in Central America, in a quadrant of 11,200 km from North to South and 4,800 km from East to West that encircles Latin America, leaving only Mexico out.

SOURCE:

http://www.resdal.org/ultimos-documentos/usa-command-strategy.pdf

Thus the whole of Latin America, from top to bottom, is tightly encircled by a ring of land, sea and air military deployment by the most powerful military machine in humanity’s history, despite the fact that recently Ecuador, Venezuela and Bolivia have brought U.S. military presence and facilities to an end in their territories, and that Brazil has not had any U.S. military base or facility of any kind for some time, every country in Latina America find themselves individually heavily surrounded by US military.

This formidable military architecture that encircles Latin America has been built and developed by the U.S. over decades and throughout the Cold War period, even though U.S. military interventions in the region well precede the East-West Cold War conflict since they go back to the 19th century. Furthermore, all US military installations in Latin America (air, naval, sea bases, etc.) have the acquiescent or enthusiastic support of local governments, with one exception: the US Guantanamo Naval Base in Cuba.

Obtained by U.S. coercion against the first independent government in Cuba in 1903. The then U.S. government forced Cubans to sign the treaty allowing the U.S. base in perpetuity, stipulating that only if all parties signatories to the treaty agree to terminate it, the lease would come to an end. The U.S. has refused to go despite the fact that the government of Cuba since 1959 utterly wishes U.S. unwanted military presence on Cuban soil to go.

Apart from the economic blockade and US-sponsored regional isolation of Cuba (expulsion from the OAS and such like), U.S. hostility to the Cuban Revolution has always had a military dimension, suffice to mention the Bay of Pigs U.S. military invasion of Cuba in April 1961, and the October 1962 missile crisis that brought the world to near a nuclear war, caused primarily, by the planning of a second, bigger, US military invasion against Cuba.

‘Regime change’ necessitated the Guantanamo Naval Base as a key military beachhead in the event of any U.S. military action against the Cuban government and its people. President Obama’s policy of openness towards Cuba, despite its pitfalls and shortcomings, make the U.S. holding onto the base an anachronism, but particularly make U.S.-Cuba rapprochement, a most welcome development, not only non credible but also an obstacle in the way of such positive developments for both countries and the region as whole. It is not the only obstacle, but one that will certainly signal a real change of U.S. policy from “regime change” to respectful and constructive engagement. The peoples of Cuba and the United States fully deserve it.

*Francisco Dominguez, Head of the Latin American Studies Research Group at Middlesex University, United Kingdom

CHAPTER 4

GUANTANAMO AND 17D

WE NEED TO TALK ABOUT GUANTÁNAMO

By Javier Ortiz

The simultaneous appearance of Raul Castro and Barack Obama on television on December 17 2014 heralded an unexpected, almost unthinkable announcement: Cuba and the United States, after a year and a half of secret negotiations, were ready to close one of the final chapters of the Cold War, or were at least making a serious attempt at rapprochement.

What followed were newspaper news headlines across the globe, hours of coverage dedicated to analysis and reactions. The whole of Cuba, and part of the United States, jumped for joy.

But on December 18, the following day, many Cubans raised the national flag to half-mast, just as they have done for decades, although there is no law requiring them to do so.

In the context of the much sought-after normalization of relations between two countries, what will be the fate of Gitmo? Will Cuba’s claim, that part of its territory be returned, be respected? Will the United States renegotiate the presence of a base that has been on Cuban soil for over one hundred years?

Josefina Vidal, head of the Cuban negotiating team, has related how every year the Cuban government receives checks for the rent of the 117 square kilometer area in Guantánamo. She notes that none of the $4,085 checks received since 1959 have been cashed, but are stored in the Ministry of Foreign Relations’ archives as “historical documents”; a quarter of a million dollars filled away as bibliographic records.

President Barack Obama’s recent declarations only focus on closing the Guantánamo’s prison, just as he promised during his first presidential campaign. But this dodges the issue of whether the territory should be returned to Cuba.

The controversial presidential candidate Donald Trump refers only to the cost of the base, estimated at over 400 million dollars per year and has said, “Maybe in our deal with Cuba, we get them to take it over and reimburse us, because we’re probably paying rent. We’re going to keep it open, but we’re going to get the cost down, because that’s ridiculous.”

Ted Cruz, who recently abandoned the race for the U.S. presidency, responded to Obama’s declaration with: “Don’t shut down Guantánamo – expand it.” Whilst another Republican hopeful, Marco Rubio, has sponsored a law preventing the President from transferring the territory of the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base to Cuba and from making any other modification without authorization from Congress.

Following Obama’s latest speech about Guantánamo on February 22 2016, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry told the press that he’s not aware of any plan to return the territory of the Guantánamo Naval Base to Cuba. “I’d be personally opposed to that”, he said.

In a recent interview with Lebanon’s Al Mayadeen, Josefina Vidal said: “In every meeting we have had with the United States we have discussed Guantanamo. We cannot say the issue is going to be solved tomorrow. In fact, the U.S. Congress, aware that this is one of our main claims, has passed legislation to impede the return of that territory to Cuba. This law was passed in late 2015, and now they are trying to pass it again as part of the budget allocation process. We are seeing how certain forces are taking positions to avoid that that territory someday returns to Cuba.”

- Raúl Castro | Presidente de Cuba

- Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez | Primer Vicepresidente de los Consejos de Estado y de Ministros

- Bruno Rodríguez Parrila | Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores de Cuba

- Josefina Vidal Ferreiro | Directora general de EE.UU. de la Cancillería cubana

- Barack Obama | Presidente de Estados Unidos de América

- Hillary Clinton | Ex Secretaria de Estado, candidata para la nominación demócrata a las elecciones presidenciales de EE.UU.

- John Kerry | Secretario de Estado de EE.UU.

- Roberta Jacobson | Subsecretaria de Estado para el Hemisferio Occidental.

But on the Cuban side, hope is not lost. The island’s government has insisted that any genuine normalization of relations between the two countries depends, among other issues, on the return to Cuba of part of its territory.

Perhaps one day in the not-too-distant-future, the excitement that December 17 generated will take place again. Perhaps on that day, television sets around the world will broadcast split-screens – one side showing US Marines lowering the Star-spangled Banner in Guantánamo; the other side showing Cuban soldiers raising their one-stared flag right to the top of the flagpole, under the burning hot sun of far-eastern Cuba.

LEGAL FACTS AND ARGUMENTS ABOUT GUANTANAMO

– Cuba considers the U.S. presence in its territory as an illegal occupation. On the basis of the principles of international law, the agreements of 1903 and 1934 were imposed on the country by force, in violation of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. International Law establishes that an agreement signed in such conditions is void ab initio.

– Cuba considers that a State’s commitment to an agreement is null if that agreement was signed under coercion or threat. The opening of Guantanamo Bay was made possible through Cuba’s forced acceptance of the Platt Amendment as a condition to terminate the American military occupation of Cuba.

– All lease agreements are temporary in nature, therefore, the perpetuity of the Guantanamo Naval Base is incompatible with that principle, as is also the signature of an agreement for an undetermined period of time -which is no different from a perpetual agreement. Leases are supposed to allow owners to recover their property at any time, or at the time agreed. All agreements must establish start and end dates. The lease agreement for the Guantanamo naval base does not establish an end date, which is a violation of the general principles of international law.

– The lease agreement of the U.S. naval base in Cuba is a perpetual agreement, without an end date, and it can only be changed if both countries agree to do so, as per the 1934 treatise.

– Another principle that Cuba considers that has been violated is the rebus sic stantibus doctrine, which establishes that a treatise becomes inapplicable when the conditions under which it was established change (independent government, the base being used for purposes that differ from the original ones, etc.).

– Obama could stop paying the $4,085-dollar lease fee, as a way to breach the agreement. The next term to do that is June 9, 2016.

– Obama could issue an executive order putting an end to the 1934 treaty. Article II, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution establishes that the executive power is vested in the President of the United States of America. Treaties are considered laws according to Article VI of the Constitution, and their execution is the responsibility of the President.

– The U.S. Constitution does not specify that the approval of the Senate is necessary to terminate an agreement.

– The U.S. President would need approval of Congress to obtain the funding needed to close the base and transfer the detainees to another location.

SOURCES:

1- Elsea, Jennifer K., y Daniel H. Else (2015) “Naval Station Guantanamo Bay: History and Legal Issues Regarding Its Lease Agreements”. Publicado el 4 de Agosto de 2015. En: https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R44137.pdf

2- Suárez Ramos, Felipa y Alina Martínez Triay (2015) “Base naval de EE.UU. en Guantánamo: Un tratado espurio” Publicado el 15 de marzo de 2015. En: http://www.trabajadores.cu/20150315/base-naval-de-ee-uu-en-guantanamo-un-tratado-espurio/

3- Micallef, Joseph V. (2016) “Could Barack Obama Give the Guantanamo Naval Base Back to Cuba?” Huffington Post. Publicado el 27 de febrero de 2016. En: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/joseph-v-micallef/could-barack-obama-give-t_b_9334352.html

THE GUANTANAMO NAVAL BASE: A FUTURE OF SCIENCE?

By Leslie Salgado Arzuaga

Barely two days before Air Force One touched down on Cuban land the prestigious academic journal Science published a proposal that looked towards the future of the Bay of Guantanamo not as a source of conflict between Washington and Havana, but rather as a bridge to help resolve the old differences between both countries.

In the article “Reboot Gitmo for U.S-Cuba Diplomacy” the researchers Joe Roman and James Kraska propose the around 120 square kilometres in the south-east of Cuba into “a marine research institution, peace park and conservation zone.’

The “audacious proposal,” as some media outlets have described it, seems to have been well received by scientists from both countries. Roman, a researcher from the Gund Institute for Ecological Economics from the University of Vermont commented to OnCuba that “US and Cuban colleagues with whom we have been talking are very excited at the idea of transforming Guantanamo into a research station and peace park. We have also heard from policymakers who consider it to be a ‘plausible’ idea. This is the first step to make it a reality”.

The researchers have thought of a model designed to appeal to both sides in a similar way and unite Cuba and the United States in joint management, rather than serve as a wedge between them, while helping meet the challenges of climate change, mass extinction, and declining coral reefs,’ the article points out.

But with a decades-old claim for the return of the territory that the US Guantanamo Naval Base occupies to Cuba the researchers recognise that there are no few challenges ahead. They see the creation of a scientific park as a point of transition towards the ultimate devolution of the land to Cuba.

“I think that after 100 years (of occupation), strongly rejected by Cuba, I think it is time to begin negotiations regarding the return of the Base. Given that the two countries find themselves in a deadlock about the Base’s future, I believe that a peace park and research station would be a third route that could benefit Cuba, the USA, and the whole region. It would constitute the first step towards the return of the land,” Roman points out.

Although the diplomatic dimension of the proposal has attracted the most attention, the scientific element that validates the existence of the research centre on the Base’s territory is sound.

From the New York Botanical Garden, doctor William Wayt Thomas – who studies Caribbean biodiversity, said to OnCuba that “Guantanamo, located in the East of Cuba is ideal, because the zone is full of species that do not exist in any other part of the world.”

Some studies published in September 2012 in the Bulletin of the Allyn Museum by the University of Florida prove it. The investigation documented 41 species of butterflies on the Military Base in Guantanamo, “demonstrating – advise the authors – that the area is a refuge for wildlife and a refuge for biodiversity”.

.

The new article published in Science on March 18, argues that “with a reduced US-footprint in Guantanamo, the large part of the land and sea could be returned to the native fauna.”

But with the Cuban authorities’ omnipresent claim for the return of the Base, why would Cuba accept an intermediate stage rather than the total return? The researchers believe that the existence of a centre of this kind “would give global recognition to the country’s conservation efforts” and cite the possibility that it might contribute to the training of Cuban scientists and students from the East of Cuba and their ability to access technology.

Doctor Wayt, who has visited Cuba five times, believes that “the Cuban biologists are very well prepared, they really know the island’s biodiversity, and are maximising their potential with the tools available,” but they are suffering from the scare access to the internet, as well as the lack of resources and the difficulty of organising exchanges. “I hope that these difficulties will be less severe in the future,” he said.

Roman and Kraska’s proposal shares this vision. They point out that “the move would extend a long tradition of U.S. naval support of marine scientific research and operational oceanography. More important, opening up Guantánamo would facilitate exchange, the two countries learning from each other. The peace park and research centre would enhance capacity, technological transfer, and scientific facilities for Cuban researchers.”

“With genetics laboratories, geographic information systems laboratories, videoconference rooms—even art, music, and design studios—scientists, scholars, and artists from Cuba, the United States, and around the world could gather and study,” the article predicts.

But first, with the US Congress’ approval, the prison on the Guantanamo Naval Base should close. When this happens science, as it nearly always does, will progress and realise its dreams.

Over the years, numerous scientific links between Cuba and the USA have produced results every single time that cooperation has been allowed to proceed in good faith, says Jaime Pastrana, president of the Cuban Academy of Sciences, in the article “Building a Lasting Cuba-U.S Bridge through Science”.

“Nevertheless, for the two countries’ scientific exchanges to be really productive in the long run, new efforts require a blank slate and guided by a new vision of bilateral relations,” concludes the scientist in the journal Science Diplomacy.

The new vision for the Guantanamo Naval Base proposes writing a new chapter for the beautiful Bay of Guantanamo that would probably begin like this: “This centre was a symbol of the conflict between the USA and Cuba and today is a space for the conservation of biodiversity through science…”

Credits

Dirección y producción: Marita Pérez Díaz. Diseño y animación: Guillo Moreno. Programación: Raidel Pérez Cuello. Realización audiovisual: Ismario Rodríguez Pérez.

Idea original: Hugo Cancio, Carla Gloria Colomé, Luis Alejandro Yero. Edición en inglés: Bárbara Maseda

Colaboración: Milena Recio, Tahimí Arboleya, José Jasán Nieves, Cherie Cancio, Alejandro Ulloa, Luis Miguel Cabrera, Ed Augustin, Osvaldo Gutiérrez.

Agradecimientos: Arturo López-Levy, Lázara Herrera, Loris Omedes, Francisco Domínguez, Elizabeth Pérez, Bonnie A. Lucero, Paola Cabrera.

Copyright © oncubanews.com 2016