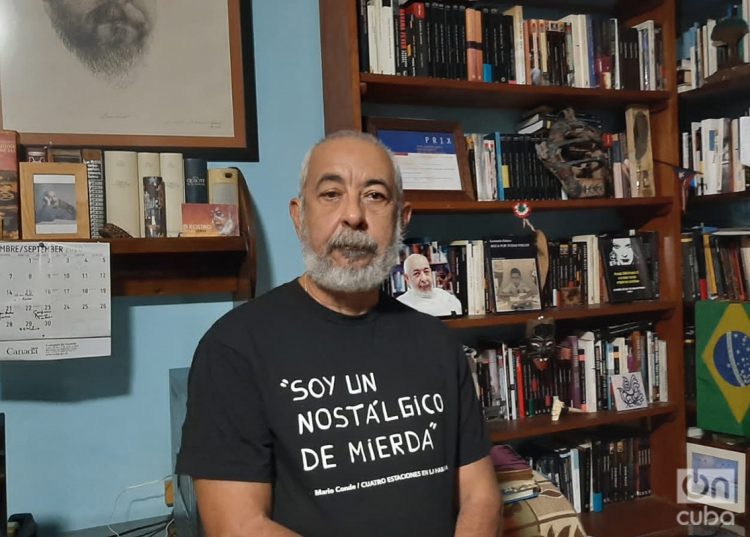

Leonardo Padura, the most published, most read, most translated and most controversial Cuban writer today, is ending this fateful 2020 at full speed. International honors, great reviews from critics and the public, intense virtual days at book fairs, conferences and seminars have kept him busy. At this point in “the championship” he exhibits a joyous fatigue, that of one who happily fulfills a destiny: writing fiction, novels, creating specular realities that delve into our intricate national being and that, whether they want to or not, reveals it.

We went to his house in Mantilla for the Christmas hug. I share our talk with the readers of OnCuba.

How have you coped with 2020?

I think this has been a rare, complicated and revealing year for almost all of us. Many things have been uncovered in the face of a phenomenon such as an epidemic that kills, and that caused us very visceral fears, because it showed us how weak we are. A single ugly, fatty molecule put humanity in check, and in the process has brought out some of the best and worst attitudes in human beings, as is often the case in critical times.

In my case, it canceled the many work trips abroad that I usually make, and the number of visits that I usually receive here in Cuba, but without reducing the intensity of work. On the contrary. So, in addition to writing, I have had a very intense schedule of presentations, conferences, interviews, always digitally, and I have attended more book fairs and literary meetings than ever. On the creative side, meanwhile, it was a good time for the final version of Como polvo en el viento (Like Dust in the Wind) and, amid all that promotional work for its release, write the first and the most difficult 50 pages of a new novel.

The use of various vaccines for immunization against SARS-CoV-2 has begun to spread in several countries. Do you think the so-called “new normal” is around one, two months away? How do you see the fight against this virus in Cuba?

I hope that the new vaccinated normal comes soon, because the fatigue syndrome is even overcoming those fears I was talking about before. It turns out that we are going to close the year with more daily cases of infections in almost the entire world, with confinements that will return, with more people that will die, with more businesses that will go bankrupt, with more disaster…. Cuba is not going to get rid of that panorama either, because it was necessary to open the borders and, through them, let in more infections.

Economically, I don’t know what the ratio of profits to losses will be, but that was what was decided, after months of work against the pandemic that achieved its control as far as it was controllable. I hope that some vaccine appears here, one of the Soberanas, the Chinese, the Russian, whatever, and I am one of those who is willing to be vaccinated. Even against rabies.

For the reasons we know, Como polvo en el viento, your latest published novel, has not had the usual promotional tours. Has this affected the reception and sale of the work? What feedback have you received from the public and critics?

The novel came out in late August in Spain, and a few weeks later in Latin America. I had scheduled tours of Spain, then Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, and to close the year at the International Book Fair (FIL) in Guadalajara, Mexico. Although I could not be in person in any of those places, I was in virtually all of them, but also in Colombia, at the FIL in Lima and the “Hay Festival” in Arequipa….

I don’t know to what extent the fact of not being physically influenced sales levels, but the novel has been among the top ten books sold in Spain, Argentina, Mexico and Colombia, that is, in the most important publishing centers of the language and in all those countries I have done different promotional activities. So the public’s response has been very favorable, and also that of the critics, who have said very flattering things about the novel, with readings that are very attuned to what I proposed with it, since it has not only been read as a novel about the diaspora and distance, but also as a story of loyalty and roots. Anyway, it seems that the novel has worked well for many readers in many countries, even since it’s a long story and with a complicated structure.

Babelia, in Spain, has named Como polvo en el viento among the 50 most significant titles of all genres, published this year.

Look at that. I didn’t know that.

In Cuba, almost simultaneously with its official launch in Barcelona, on August 25, the novel began to circulate, in pirated electronic edition, although not for profit, on social networks.

Well, “not for profit.” Some people offered it for sale, even advertising in Revolico. The fact is that a copy of the editorial PDF left Colombia and started circulating, and then the copy of the official digital format joined it. That is something that today is almost normal, although it is still painful for writers, who live off their rights. But in the case of Cuba, I say it sincerely, it has been a satisfaction, because I don’t know when Cubans will be able to read copies of the novel that, I hope, will be published by some publishing house here.

The previous novel, La transparencia del tiempo, which is from 2018, has not yet come out; maybe it will be printed next year. But those pirated copies have circulated profusely in Cuba, and many people have told me something about the novel, and hence my satisfaction. It is a book that interests me very much that Cubans can read, given the difficulties, delays and obstacles of our publishing system, which in the end will print three or four thousand copies of the work. Keep in mind that in Spain it came out with a first edition of 23,000, and there are already five editions (more than 40,000 copies). I am comforted that my compatriots who live on the island have been able to read the book and identify with the story, or stories, that I narrate in it.

Is it true that before undertaking any major narrative project, you read for the umpteenth time Conversation in the Cathedral, the famous novel by Vargas Llosa?

It’s true. And I do it because that specific novel mobilizes me, provokes me, challenges me. So far it hasn’t stopped doing that. Its structure, its characters, its narrative strategies are overwhelming, and the book becomes something of a goal that I always aspire to. Whether I get near it or not is something else, the important thing is the incitement.

You recently received the Carlos Fuentes medal, one of the most important distinctions granted by Mexico, during the Guadalajara International Book Fair, this year held virtually. Is the author of Terra Nostra a writer you particularly admire?

Yes and no. Among the authors of that platoon in which Carlos Fuentes appears (I can’t say it’s a generation, nor a group, so platoon) there are others who are more related to me. There is the case of Vargas Llosa, which we already talked about. There is also Carpentier, about whom I have written two books and several essays, which has given me a problematic view of History; or Cabrera Infante, with his Havana geography and, above all, with his use of the literary Havanan, to which I am indebted. I add Rulfo, from whom I learned a lot in restraint, in the need to “write with the ax.” Of Carlos Fuentes I admire, above all, his first works, especially three: La región más transparente, La muerte de Artemio Cruz and the short story “Aura.” I think that’s the best of Fuentes, although the one from Terra Nostra or Cristóbal Nonato is also an impressive storyteller.

In any case, receiving the medal that honors him and that honors me has been a great joy. If you know the list of authors who have won it before, you will know why.

Herta Müller, Jonathan Franzen, Nélida Piñón, Paul Auster, Salman Rushide, among others.

I regret that our country’s cultural authorities and the press, insisting on their policy towards me, have not disclosed that a Cuban writer is (with the award) among that list of illustrious people. I have the impression that Cuban literature should care about this recognition. I don’t know how long there will be people in Cuba who decide what we should or can read, see and know.

Name the five writers who decided unequivocally your inclination for the practice of literature.

I’ve already mentioned some, all Ibero-American authors. Five others are very easy to mention: Hemingway, Salinger, Truman Capote, Sartre and Camus. Without forgetting the revelation that Vázquez Montalbán and his novels of the character Pepe Carvalho were at the time.

On August 15, 2019, you visited former President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva in the Curitiba prison. That fact was controversial for both extremes of the Cuban political spectrum. In statements given to the press on that occasion, you pointed out that “it is a universal right of man to have freedom of political opinion, as long as these actions, ideas, attitudes don’t generate manifestations of hatred, xenophobia, discrimination or persecution of other people.” As far as I know, among all the official national bodies only Cubadebate echoed the event: it reproduced a note that appeared in El Público, in Spain. Why do you think you were so harshly criticized then?

What I said a few minutes after I left the jail, while waiting for the flight from Curitiba to Sao Paulo, is what I still maintain today, because I continue to think the same about man’s individual and social freedoms. The criticism of some and the silence of others are the usual attitudes that I receive for each one of my works, for every gesture I make and, in some way, it reflects the extremes between which the opinions of my compatriots from outside and inside move. The stick because you row and the stick because you don’t row, it was said before. Although behind many of these opinions, criticisms or even silences I think I notice other motivations, even more perverse and poorer than political leanings.

In my case, and particularly in this case, I only responded to what I consider a duty: fidelity. For years, when The Man Who Loved Dogs became a reference book in Brazil, I have met several times with President Lula at his foundation. He had read the book, he wanted to comment on it with me, and I agreed, because I have a confessed admiration and respect for the social policies of the PT during his years in government, when it favored millions of Brazilians. That’s what the statistics say, not the speeches.

The same Lula who befriended me, when he learned that I would be in Brazil, asked my editors to facilitate the visit. Of course, I accepted. I went to see a friend when he was going through difficult time, I went in a personal capacity, and I would go again if it was the case.

And if I hadn’t been able to do it, what would those who criticized me for going have said about me?

Do you consider freedom of expression, in the Cuban context, a utopia or an aspiration that could become a reality in the more or less near future?

Freedom of thought, expression and creation is a social necessity. Not having it implies a burden, a regrettable absence. In Cuba we have lived moments of intense censorship, of works and of creators; times when a single thought has been publicly imposed and unanimity has been demanded. That unanimity is utopian; no society can be unanimous, and no society should limit the right to disagreement, except those ideas that are harmful to human dignity. Today the world is living a circumstance in which the flow of information is practically unstoppable, and people read, and then think. People who read and think.

I have been the victim of censorship processes. The most visible was the film Regreso a Ítaca, “deprogrammed” from a Havana Film Festival. And others more invisible, such as—necessary redundancy—the policy of invisibility of my work, because it is banned or limited in the country’s media. Like any society, Cubans need those freedoms, which are even endorsed by the Constitution, but which certain people always try to restrict, for political or circumstantial reasons.

He who thinks differently in many of the alternatives on the social spectrum is not always the enemy. And having a more realistic vision, permissive with differences, is a necessity in a society that even lived through the well-known repressions for religious beliefs or sexual preferences. Do you remember that? There are people for whom these events never occurred in Cuba.

Since it became legally possible in 1996, I acquired the status of an independent artist. I have practiced that labor independence, even legal, from my writing. If I had not felt free, I would not have written the novels that I have written. Novels and freedom for which I pay consequences, like those censorships and silences that I told you about before. Novels like Herejes, in which I reflect on freedom of choice and thought, what the Jews called “free will,” and on the consequences that practicing that freedom can bring us, even in societies that claim to be more democratic and permissive.

Can we Cubans abstract from the historical influence that the successive governments of the United States have supposed, to create a society that satisfies us, that includes us in all the extension of the word “diversity,” beyond the status of a besieged plaza?

I wish we could stay out of the tensions that relations with the United States imply. That encompasses everything, from culture to economics, from politics to the status of the nation. That is a process with a long history and heavy consequences, which would be difficult to outline even in the space of an interview. It is a phenomenon that I have studied a lot for the novel I am writing, which has a sector of the plot that occurs in the early twentieth century, a particularly critical period of these traumatic relations. That’s why I will just tell you that Cuba has the same right as any country to settle its internal issues among Cubans. These decisions must take into account all Cubans, so that Martí’s mandate to build a homeland with all and for the good of all does not remain a slogan.

In this Christmas so atypical that it’s almost not, what would be your wishes for the Cuban people, that economically and socially, pandemic aside, has had a critical year?

I would like the internal tensions to drop and … the announced electricity tariff. The arrival of monetary unification has been like the starting signal in the money race. Those who set the goal took too long to say what that process would be like, and meanwhile the country lived in familiar economic tension, a psychological burden that was added to the heavy burden of the lack of supplies. Now that the measures are known, concern and popular discontent over some of them have not stopped growing. And I speak from what I see and hear, not from what the Cuban media publish.

It is said that things must be changed, that our society is not perfect, that the productive forces must be released, without haste, without haste! But people’s lives go fast, they don’t stop, and one year goes by, another begins, and we are still in tension. If only they would vaccinate us soon! 2021 has to be a better year, and I hope, I trust, I hope it will be for all Cubans. We greatly need it.