“I traveled to Havana several times in late 1979 and early 1980. Without an immigration agreement since 1973, the Cuban government was concerned about the hijackings of planes and ships, and the assaults on embassies. Fidel has warned it, before the crisis broke out. I shared his concern. Mariel could have been avoided.”

This is how Peter Tarnoff, Special Assistant to the two Secretaries of State that the Jimmy Carter administration (1977-1981) had, told me. More than two decades had passed since then, but his interest in Cuban things was still alive, and I wondered what was going on here, as we made plans to teach U.S.-Cuban relations in a course we would both give.

The years of rapprochement

Just as Obama’s turnaround on December 17, 2014 cannot be understood without the background and context in which it took place, neither can the Carter administration’s rapprochement with Cuba be explained as a bolt of lightning in a clear sky. Doing so requires going beyond declassified documents, to examine the real theater of politics, where the intentions and wills of the characters, as in Greek tragedies, have to sail with opposite winds.

Between 1970 and 1974, Chile, Peru, Jamaica, Trinidad-Tobago, Barbados, Guyana, Argentina, Panama and Venezuela were reestablishing diplomatic and commercial relations with Cuba. In 1975 Colombia would do it; and the Organization of American States (OAS), without U.S. resistance, would leave each state free to normalize relations with the island. The total hemispheric isolation maintained for six years, with the sole exception of Mexico and Canada, crumbled.

This attitude towards Cuba made it clear that if the United States proposed a renewed policy towards the region, a change in relations with the island was essential.

The select committee that had toured the region in 1974, and that sponsored the Linowitz Report, would ratify it: Cuba and the sovereignty of the Panama Canal were the test-cases to measure a new U.S. policy, according to what the governments themselves said.

Within the framework of the so-called “new dialogue” for Latin America, promoted by Henry Kissinger, certain secret talks had begun with Cuba in 1974. President Ford would authorize U.S. subsidiaries in South America to trade with the island. In the diplomatic field, progress was made along a path that seemed to lead to rapprochement.

Since 1971, initiatives to end the embargo and normalize relations had been presented in the United States Congress itself. Senators like Fulbright, Kennedy, Javitts, McGovern, and Pell, and representatives like Solarz and Whalen, had traveled as congressional ambassadors to Havana.

At the same time, and despite the signing of an agreement on plane hijacking in 1973, piracy and terrorism intensified. The swine fever virus would devastate the Cuban livestock population in 1971. A wave of attacks against embassies and fishing boats would be at their height in 1974. For its part, Congress had rejected, in 1975, the resolution to lift the blockade proposed by Representative Bingham.

The virulence of the opposition to a change in policy towards Cuba was still alive.

When, in December 1975, Cuban troops crossed the Atlantic to defend the recently launched MPLA government in Angola against the South African invasion from the south and the Zaire attack from the north, the U.S. reaction was to freeze the dialogue with Cuba. Even so, in the first months of 1976, Fidel Castro would declare that “we would be willing to maintain normal relations with the United States on the basis of mutual respect and sovereign equality, without renouncing a single one of our principles, and without ceasing to fight so that in the international sphere the norms of peaceful coexistence are applied.”

For the Organization of African Unity (OAU), and for figures who would play a prominent role in the diplomacy of the next Carter administration, such as Andrew Young, that military collaboration was a factor of stability and peace in sub-Saharan Africa.

In the last year of the Ford-Kissinger administration, acts of terrorism would pick up again, reaching their climax with the attack on the Cubana Airlines plane in Barbados. Cuba would denounce the agreement on plane hijackings, alleging that the United States was responsible for the sabotage carried out by terrorists residing in its territory and historically linked to the CIA. It is not by chance that these operations were felt in countries that had reestablished relations with the island in recent years.

Although Angola and terrorism slowed down the dialogue, the factors in favor remained. In addition to the attempt to renew its relationship with Latin America, the post-trauma of the U.S. defeat in Southeast Asia prompted the search for a renewed political projection. Those were the years of the Vietnam syndrome and détente with the USSR. This climate favored Jimmy Carter winning the 1976 elections.

In the first year of the new administration, two diplomatic offices with the range of interest sections were agreed upon in Havana and Washington and an agreement on fishing and maritime limits was signed, still in force. For the first time Cuba and the United States collaborated in the prevention of terrorism. The prohibition to visit the island printed in U.S. passports disappeared, the application of the blockade regulations was reduced, the spending of dollars was allowed and certain food sales were authorized. Although the plot of economic restrictions was maintained, groups of businesspeople visited the island, reaching more than two hundred corporations interested in exploring the possibilities of bilateral trade.

According to Alamar Associates executive Kirby Jones’ list, these included mining and chemical-energy companies such as Amax and Engelhardt; aerospace transportation, such as Boeing and McDonnell-Douglas; linked to the agro-industrial sector, such as Caterpillar and International Harvester; electronic equipment and computers, such as General Electric, RCA, Xerox and HoneyWell; food, such as Coca-Cola and Uncle Ben’s Food; entertainment, such as CBS Records and the New York Yankees; and financial institutions, such as Prudential Insurance:, Security Pacific, First National Bank of Chicago and American Express. Some of them had been nationalized in 1960 but were interested in exploring new businesses with a post-blockade Cuba.

Despite the normalization plan towards Cuba with which Carter began his term, the adverse factors did not disappear. In the first hundred days of the new administration, the invasion of the Zairian province of Shaba by a group of Katangese rebels gave rise to a premonitory incident, which would determine an incessant series of contingencies — never fully clarified — that contributed to once and a while clouding relations.

Since mid-1978, together with a second incident — also insubstantial — about Shaba, some surprising “Cuban MiG 23” would appear, with a “strategic reach” capacity, which served to justify the decision to resume military intelligence flights over the island.

Despite the negative trends, the forces driving the dialogue continued to advance. This year an agreement was signed on the coast guard — which included the prevention of drug trafficking and terrorism — and high-level diplomatic meetings were held.

Cuba made the unilateral decision to release 3,000 prisoners (some convicted since the years of the Escambray war), as well as to allow visits by the Cuban community, within the framework of a dialogue initiated with a broad sector of emigrants, in November 1978.

Fidel Castro would declare, on January 1, 1979: “Cuba is not opposed to normal commercial and even diplomatic relations with the United States. We sincerely believe in the need for peace and coexistence between different social regimes.”

On the Cuban side, the main obstacle in relations with the United States was the blockade. For the United States, in that second year of the Carter administration (1978), it was neither the Cuban alliance with the USSR nor the guerrillas in Latin America (Colombia, Nicaragua, Guatemala), but military collaboration in Africa. That year, the sending of Cuban troops to Ethiopia to repel the Somali attack on the Ogaden territory revived concern.

In 1979 new problems would appear. These took the appearance of Soviet submarines in Cienfuegos and of a “Soviet combat brigade” near Havana, where the 6th Summit of Non-Aligned Countries was about to open.

Despite the fact that none of the incidents yielded anything concrete (the “Soviet brigade” had been here since 1962), Carter issued Directive 52, which increased surveillance of Cuba, established the Caribbean Joint Task Force in Key West, increased military maneuvers in the region and increased the number of forces at the Guantánamo naval base.

At this point, however, it was not the presence of Soviet military advisers on the island or Cuban troops in Africa that set the course for U.S. concerns in the hemisphere directly related to Directive 52. It was about events taking place in the Caribbean Basin, in two countries much smaller than Cuba: Nicaragua and Grenada.

President Carter had identified a new “contentious issue” surrounding Nicaragua as early as February 1979, when the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) had not yet overthrown Anastasio Somoza, but the scenario of a plausible “Cuban intervention” was emerging. Barely a month later, in March, the New Jewel movement, led by Maurice Bishop, had overthrown the Gairy regime on the island of Grenada.

These specific events had the virtue of turning on that old light bulb, which nobody remembered: “other Cubas” in the backyard of the United States.

Fidel Castro would state: “We do not follow a deliberate policy of confrontation with the United States. We do not even refuse to talk and we are not against an effort to improve relations if that in some way helps to create a climate of peace in this hemisphere or in the international arena.”

However, as would happen so often — before and since — the factors that usually determine U.S. policy, regardless of what was happening in Cuba or elsewhere, had unleashed their own dynamics.

Mariel would be the last episode of that collision course already underway. More than a cause, it was a consequence of the chain of adverse factors that would put an end to the rapprochement between the United States and Cuba. Back then there was no economic crisis like today; but migratory pressure, encouraged by the very policy of dialogue with emigration initiated by Cuba in 1978.

In his speech on Women’s Day, March 8, Fidel stated that the United States “encourages illegal departures from the country, the hijacking of boats, little less than receiving as heroes those who hijack a boat…. We have asked them, we have demanded that they take action and discourage such activities….” Forty-three days later, the port of Mariel was opened.

For three weeks, President Carter welcomed the Marielitos with “open arms and hearts,” in his own words. That crisis, once again, would get out of the hands of the U.S. government and would be used by the Republicans to dress their table at the juncture of the election year. The last months of the Democratic administration passed under a strong anti-Cuban campaign regarding Central America.

Despite everything, Carter let the Cuban government know that if he won the elections, he would persist in his goal of dialogue and normalization.

Extensive examination of the Ford and Carter years makes it possible to appreciate that the decisive factors in the erosion of dialogue were not bilateral (they have almost never been). Despite the Vietnam syndrome, the détente with the USSR and the rethinking of the policy towards Latin America, Cuba remained a “domestic” issue in the United States.

“Domestic” did not mean then, as now, the Cuban-American right in Miami, but rather the electoral struggle between Democrats and Republicans, present in Cuba policy since 1960.

In this reading, Cuban policy in Africa was deciphered as a Soviet move on the board of that continent, the same as the revolutions in Nicaragua and Grenada, the rise of the national liberation struggle in El Salvador and Guatemala, so that the “Cuban threat” would return to the Latin American agenda of the United States. The way was prepared for a new cycle of hostility centered on the Central American wars, which would take over the 1980s.

An open epilogue

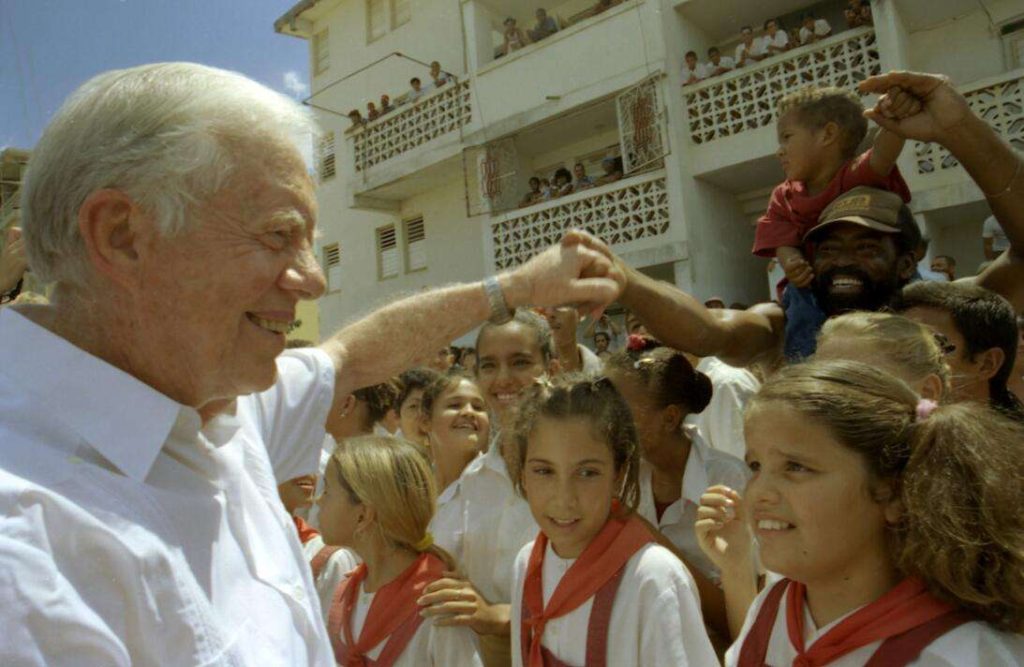

Twenty years later, I met Bob Pastor in Havana, in charge of Latin America at the Carter administration’s National Security Council. We talked for a couple of hours about Cuban things, which I later heard covered in Carter’s speech on May 14, 2002, at the University of Havana, during the first visit by a former U.S. president to Cuba.

Listening to him in the Aula Magna was Fidel Castro. His words were broadcast live, on radio and television, throughout the country. The following day, they were reproduced in their entirety in Granma.

Carter advocated a peaceful and harmonious coexistence, demanded the lifting of the blockade and the ban on travel to the island. In addition, the advance in human rights was a main flag of his foreign policy in his years in the White House, and he recognized that in the United States they were not “perfect.”

He defended the idea of a Cuba integrated into Latin America, reincorporated into the OAS, a participant in the Summits of the Americas; a Cuba in which there could be disagreement with the government, Cubans could travel freely, an exchange between Cubans from inside and outside would be fostered. He asked that the precepts of the Constitution that consecrate democracy and freedom be applied, so that Cuba could once again join “the community of democracies.” He claimed that the United States should take the initiative. And that for the majority of Americans, including himself, economic and political changes should be decided only by the Cubans.

In 2002 the Bush administration was not very in agreement with that visit to Havana. Rather, he took advantage of it to invent that Cuba was producing weapons of mass destruction, making use of its biotechnological facilities. Carter limited himself to responding that none of the information shared with him by U.S. security agencies prior to his trip included that “Cuban threat.”

The reader will guess what points of that speech in the Aula Magna Pastor and I had debated, including the question of the main actors in a domestic political change, the reinsertion in Latin America and the Caribbean, and in the international system.

Rereading the speech now, I find, however, that things have changed a lot more on the side of Carter’s and Pastor’s wishes than many thought then or think now. What has moved the least is the part of those wishes about U.S. policy.

The hope that those ideas can prevail is enough to recognize their merits, as well as to learn that agreeing to our disagreements is a step on that path.