Not 24 hours passed after Dani Hernández was appointed head of the Fernando Alonso National School of Ballet for him to kindly agreed tp a telephone conversation with OnCuba. It’s flattering to know that this is a scoop and his first contact with the press.

The data is not fatuous. He gives signs of a collaborative spirit, a clear and diligent character and a tremendous desire to communicate his intentions at the head of the strategic reserves of the National Ballet of Cuba (BNC) and other groups that perform classical dance.

With these virtues, and others assumed but less ostensible in a telephone conversation, Hernández (Remedios 1989), must face a mission worthy of the circumstances.

Always challenging because they are difficult, he will have to move between changeable realities and will have to guarantee, despite or thanks to it, the medium and long-term renewal of the most mythical and universal of the island’s cultural institutions.

The times when two characters of the 20th century: the dance diva, Alicia Alonso, and the leader of the Revolution, Fidel Castro, spoke on an equal footing and resolved problems by telephone or in person are long gone.

Founded by the legendary dancer and choreographer in 1948, the company is the only functioning entity that is a protected asset at the highest level, having been declared heritage of the Cuban nation in 2018.

Royalty and the jet set of conspicuous societies and Cuban or Latin American workers and farmers who have never known the refrigerated awe of a theater have been captivated by the vibrant choreographies and talent of Cuban dancers throughout decades.

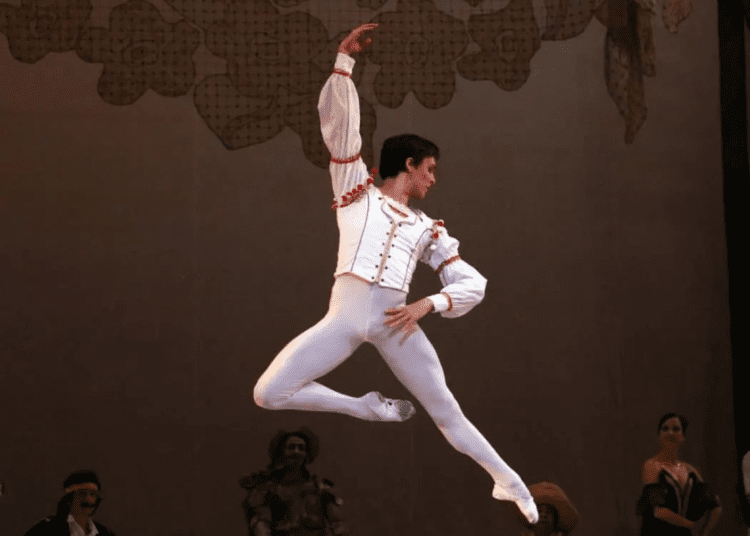

In the profuse list of such memberships, the name of Dani Hernández stands out, the first solo dancer of the BNC and acclaimed by the specialized magazine Dance Europa as the seventeenth best dancer in the world in a group of one hundred selected in the 2010-2011 season.

Trained by maestros who defined the making and profound scope of the Cuban academy, such as Fernando Alonso, Ramona de Saá and Mirta Hermida, Hernández stands as a “great reference for the Cuban school of ballet,” given its “technical and stylistic rigor, as well as his experience as a teacher.”

In 22 minutes of conversation, the brand-new director of the highest Cuban ballet academy, one of the leading institutions of the dance tradition of the island and Latin America, puts his cards on the table.

A key man for a key future

First of all, congratulations on your appointment. An enormous responsibility, right? You have the future of ballet in this country in your hands. How do you assimilate this change in your life?

As you say, it is a great responsibility that I am assuming at this moment, because it is not only the future of all the generations of dancers who will be trained after my appointment, but also about the future of ballet in Cuba, about the future of the Cuban school of ballet and that is something that I assume with the greatest commitment. Until now I have always defended the Cuban school of ballet as a dancer and as a Cuban; but from this position as director I also assume it as a teacher, as a continuation of the legacy of the great maestro Fernando Alonso.

Tradition and modernity

What has the director of the National Ballet, prima ballerina Viengsay Valdés, asked you to do at the head of the School? She is carrying out a very interesting agenda, managing balances between tradition and modernity. Is that spirit of renewal going to reach the National School of Ballet under your command?

Of course! It is something that Cuban ballet now needs, it is part of the same dialectic that our founders, Fernando, Alicia and Alberto Alonso, understood, that ballet should develop in step with the times.

Today dance is seen from another perspective, another view, other ways of doing and other ways of interpreting, and for the Cuban school of ballet to continue to endure and maintain itself at a global level, we have to look at these new trends and forms of dancing that the world has.

Would it imply that the School will open up to experimental methods of dance pedagogy, for example?

Regarding pedagogy, we have a good basic structure, regulated with its methodology and study plans. It does not mean that we always have to adapt, improve and develop these study plans to take our methodology to other levels.

The thing is that everything is flowing incessantly, especially the arts, the sciences….

It is a fact that the way of doing, of dancing, of interpreting from ten or twenty years ago is not the same as today. These new ways of doing things and these new dancing trends, in which the choreographers are experienced, make the School in some way rethink its methodology; it is not to change, but to adjust and incorporate, based on the academic prism that the School has, which in principle is Cubanness, the identity that defines Cuban dancers.

Identities

Now that you mention it, how do you compare the Cuban school of ballet in relation to other similar ones in the world? For example, the Russian or the Danish.… What traits would define the profile of the Cuban school?

The main element that defines all schools is the essence of their culture; the essence of the country, of that place where it is developed. We are not exempt from such a relationship. It was precisely this that distinguished the Cuban dancers when they appeared at the Varna competition, and Arnold Haskell, the English critic, defined that moment in the 1960s as the Cuban miracle.

It was something that no one imagined would happen, since there were these other five well-defined schools [Italian, Russian, English, Danish and French schools]. And the fact that the Cuban school of ballet appeared and provided that defining distinctive element of a new way of doing, interpreting, and approaching dance, makes us stand out from the others, makes Cuban dancers even sought-after in all parts of the world, where they are appreciated for their elegance, projection and for one of our main characteristics, which is dancing as a couple, for that internal force that both the male and female dancer imposes on the way of doing any work.

Obstacle race

The School is not in a bubble, so unfortunately it is facing a country that suffers many difficulties of all kinds. How will you deal with these difficulties on a daily basis at the National School of Ballet?

Well, I think that if there is something very important, it is that the School has the full support of the highest leadership of this country. Obviously, we are not exempt from the country’s difficulties, but we do have the human capital and the willingness to help, collaborate and contribute to the development of ballet in Cuba, since it is national culture’s flagship.

And when it comes to battling, it’s about contributing together. I have the support of the teachers, the parents, the students, I have the support of the same people who for so many years have continued to push the School forward, and that is very important. Above all, there is unity of purpose, that all workers feel identified and there is a sense of belonging to this building, for what ballet represents in Cuba and the weight and prestige of the Cuban school worldwide.

Iron hand or silk glove

How do you see yourself as a director? Will you have an iron hand or will you put a silk glove on that iron hand? Because the ballet career is extremely demanding, extremely hard, if you want, of course, to achieve admirable results. You yourself, until not long ago, were a student at the School. How will you handle this dialectical game between institution and students?

If anything is going to help in my projection, in my School project, it is precisely the fact of having gone through it, of having had excellent teachers, excellent pedagogues who trained me. All of this means that my vision starts from that perspective, from the perspective of discipline, of dedication. It is certainly a career of great sacrifice, which is very demanding, from the teacher as a trainer and demands from the student as a dancer.

You are facing teenage students.…

These are complicated ages. It’s a reality. At this time, the School has two levels, elementary and middle, within the same building and they are difficult ages, but the pedagogy that is used, that way that the teachers have of teaching, makes the student understand and contribute to things working the right way.

I don’t think you have to have a hard hand or a soft hand. Mutual respect and discipline (something fundamental in the study and development of ballet) is the key to the result of what I want to project as a director. And I hope the results will be seen soon; it is something that Cuban ballet is crying out for right now.

I have to recognize the work that teacher Ramona de Saá, the dear Cheri, as we all know her, has done for so many years; the work that all the teachers of the first training generations have done and have continued, that even today many are joining in the mission of improving and perfecting, makes me feel accompanied and safe in any step I want to take.

The Maestro

Remembering the maestro Fernando Alonso, an inspiration for anyone due to his perseverance and discipline, he was a model for you.… Is it true that he called you “prince”?

I owe my career to maestro Fernando Alonso. It’s a reality. All the knowledge I have, all the way of doing things, of dancing, of understanding, I owe to him.

In my second year of study here (because I am from Remedios and in Villa Clara I studied my five years of elementary level) at the ENA, where I joined at the intermediate level, I had the joy of working directly with the father of ballet in Cuba and that too makes me feel committed to the pedagogical work, to the seed that perhaps at that time I did not understand, or perhaps I did not know how it would germinate, and I believe that the result is today.

On many occasions, although it was not written down, people who were close to the maestro heard him say several times that yes, I was his last prince.

Behind or in front of the desk?

The question may be mine as well as that of your many ballet fans or lovers and also of readers who are looking at this change in your life. Being still a young dancer, full of abilities, will this new and great responsibility mean the end of your career on stage?

As you say, it is a responsibility that requires a lot of time and dedication, because it is a complex task. It is not only the artistic part, it is also the administrative part, the teaching part. It is the work not only in Havana, here at the National School of Ballet, but the methodological and pedagogical work in all the art schools in which ballet is taught.

Of course, the National School governs the entire teaching process.…

That’s right, it governs both inside and outside of Cuba and that involves hard work that will take me a lot of time as director; but I don’t plan to give up my career immediately. Quite the opposite. I have a faculty of teachers, with a team of collaborators around me who are supporting me and offering the possibility of continuing with my dancing career.

The director of the national company, Viengsay Valdés, also advocates for this; because in some way, being a first dancer, I am a reference, not only for my colleagues in the company, but I am a reference for the students I am going to train. And that is necessary, it is necessary that they continue to see me active on stage.

I feel healthy and capable of tackling both tasks. I have the support of many people, my family, which is unconditional and fundamental support, because they know the sacrifice and what those hours away from home entail; those hours when I have to spend a lot of time in the classrooms; dedicate myself not only to the School, but also time to myself, as a dancer, so as not to lose my training and continue to be at the level of a first dancer and remain among the leading figures of the National Ballet of Cuba.

Of all of them, a bullfighter

You have done the Albrecht, from Giselle, the solo from The Death of the Swan, the Basilio, from Don Quixote, in short…. What is your favorite role of those played throughout your career?

All dancers say that we like all the roles and it is a reality, because each role has something special. Apart from the distinctive touch that the dancer gives it — which is typical of his personality, his way of being and performing —, there are some roles that always come out as favorites.

In my case, Carmen’s Escamillo is the favorite. It is a reality that I admit. If I were given a choice among all the roles I would like to play at some point, I would always choose Escamillo.

Why?

Because of the characteristics that he has, because he was a character that I had to work on a lot, because of my condition as a dancer, because of my biotype. I was always characterized as a danseur noble, that dancer who only plays princes, and when I had the opportunity, the great challenge of assuming that character forced me to study and work hard to find its essence; not only in what I wanted to project, but in all those generations of great Escamillos that have passed through the history of Cuban ballet; especially that of Jorge Esquivel, one of my main references in male dance.

I dedicated myself to individual study to understand what a bullfighter is like in a bullring, and how I could acquire and assimilate all that knowledge to project it on stage. Many other characters have emerged from there.

I am becoming more and more interested in the artistic part, in the histrionic part within the company. Not only do I play the roles of lead dancer, but I have begun to investigate and experiment within the character roles, which are very, very complex; without being the main character, they carry a great weight within the work and a deeper characterization and study. And yes, Escamillo, from Carmen: he is that iconic role that I would always like to play.

A Remedios reveler

A boy from Remedios, a town that has given brilliant figures to Cuban culture (Alejandro García Caturla, Zaida del Río, Carlos Enríquez), how do you see yourself if you look at the depths of your life, leaving your hometown, coming to Havana, the big city, and then traveling around the world, in the most dazzling theaters, being applauded by people very knowledgeable about ballet? Do you have a couple of words to encapsulate this magnificent life experience?

You tell me and my whole body vibrates! I never really imagined I would get to where I am. It is something that I am grateful for and that I must give thanks to the training and development of ballet in Cuba; to the vision that was had, that people like Commander in Chief Fidel and Alicia and Fernando had about massifying and taking culture to all corners of this island. I am a product of that great project and that idea.

I have never given up on Remedios, wherever I go I say that I’m from Remedios, that I come from a small town of red earth, north of Villa Clara; that despite studying a career that is somehow seen as elitist and perfectionist, I am still that rural guajirito, that Remedios reveler who misses his hometown, but at the same time is grateful for the great support that people have always given me, those who saw me be born, the people who have seen my career develop and yes, become a first dancer, the best in my career, and be able to study at this magnificent school, and then reach the National Ballet of Cuba, being able to travel practically the entire world, to take Cuban art and the Cuban school of ballet to all the corners where we have performed, to be a standard bearer, to be a representative of our School.., because it makes me feel honored to be from Remedios and to be Cuban.

You have really moved me with those words.… Just a small important fact. I can’t find the year of your birth anywhere on the internet. Are you hiding it?

No, not at all! (Laughs). I was born on January 2, 1989 in a very complicated period for our country, we were practically entering the Special Period; but I don’t hide that data at all. Quite the opposite. I am a very simple person, I consider myself a very simple person, very approachable in all aspects and I think that is part of the idiosyncrasy that Cubans have. Being able to be yourself without having to pretend anything; wanting to continue being part of the people, to contribute to the people, to not add things that are not necessary in life. I think that contact with everyone and being accessible to everyone has allowed me to have all the support I have today.

You haven’t become very high and mighty….

No, I don’t think so, I don’t. It is very difficult, because my family is a very humble family, which always taught me that everything you do with sacrifice, with determination, life will reward you and I believe that the result of all things is in this. They have taught me to be a simple, honest, direct person; to not hide behind false appearances.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES OF THE FIRST DANCER DANI HERNÁNDEZ, recently appointed director of the Fernando Alonso National School of Ballet.

He was born in Remedios, Villa Clara. He began his ballet studies in 1997 at the Olga Alonso Vocational Art School in Santa Clara and continued them at the National Art School. Prominent teachers and choreographers contributed to his training, including Fernando Alonso, Ramona de Sáa and Mirta Hermida.

During his school years he won the silver medal in the International Competition for Ballet Students, held in Havana in 2006.

After graduating in 2006, he joined the cast of the National Ballet of Cuba, under the artistic-technical direction of Alicia Alonso. In 2009 he was promoted to the rank of First Soloist and in 2011 to First Dancer. His repertoire includes the leading roles of the great romantic-classical tradition as well as contemporary creations by Cuban and foreign choreographers.

With the National Ballet of Cuba, he has performed in countries in America, Europe and Asia. He has been a guest artist at important galas and festivals worldwide. In 2012 he participated in the Gala for the 20th anniversary of the creation of the Alicia Alonso Dance Chair at the Complutense University of Madrid, the root of the current Alicia Alonso University Dance Institute, attached to the Rey Juan Carlos University, Spain.

In the period 2011-2014, he was proclaimed by Danza Europa magazine as one of the most outstanding dancers in the world.

In 2017 he received the title of Illustrious Son, awarded by the Assembly of People’s Power of the city of Remedios.

In 2019 he was awarded the Lorna Burdsall Prize, awarded by the Association of Performing Artists of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC), and in 2023, he received the Artistic Legacy award from the International Classical Ballet Festival of Mexico.

In 2020, he obtained a Bachelor’s Degree in Ballet from the Faculty of Dance Art, University of the Arts, Cuba (ISA).

He is considered one of the most valuable male exponents of the Cuban school of ballet.