They call him Cuba, because his name is Adrián Cuba (Havana, 1965), and he is a very unique artist, who does not discriminate when creating, surfaces or supports. Since visually the world seems insipid to him, he tries to wash its face and decorate it with figures and colors. If he sees a coffee pot, he immediately wants to decorate it. The walls, whether of a hotel or a children’s hospital, incite him and challenge him. He travels through the streets of his city by car, on foot, and… in dreams that are going to be filled with meticulous brush strokes. His thing is to paint, which he assumes as fate (something that is going to happen inexorably), as a mission, and as a destiny.

He has a degree in Design and has also ventured into ceramics and set design for television. His works have been exhibited, in personal and collective exhibitions, in Cuba, Spain, France, Panama, Italy, Mexico, and the United States. His ceramic or painted murals are located in institutions in several provinces of the island.

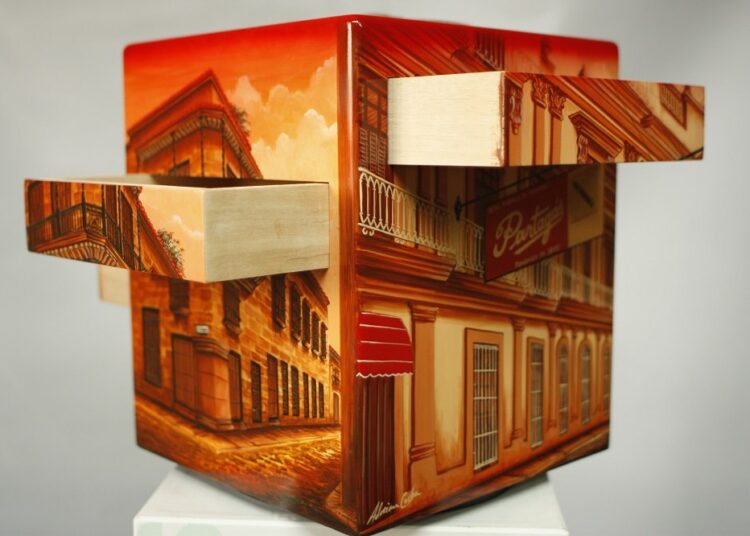

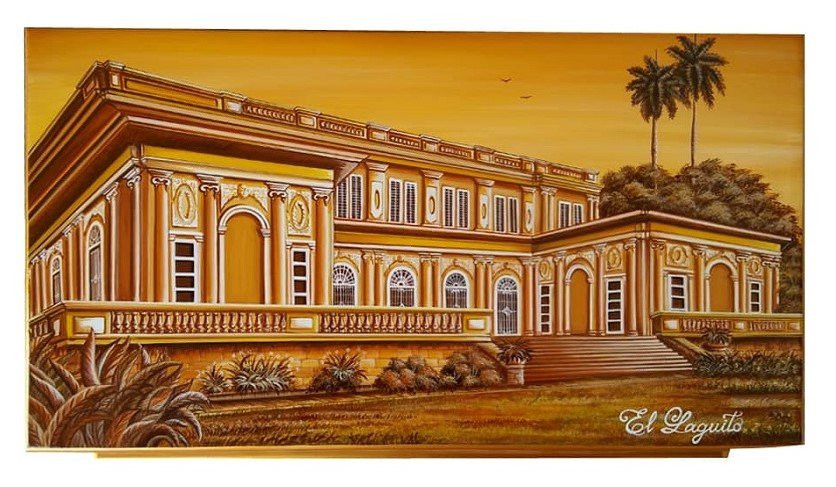

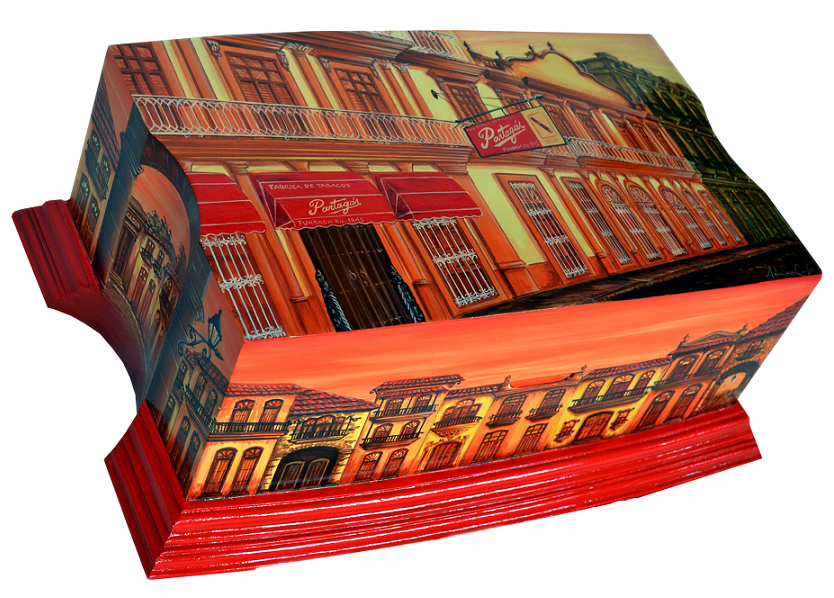

Since 2010 he has decorated humidors, an activity for which he is mostly known. Since then, more than 45 pieces have left his workshop and can be found in a dozen countries.

He tells us:

“Several years before thinking about painting humidors, I started smoking cigars, in honor of my grandfather, a great fan of cigars. He had friends with whom he shared conversatios and smoke, and there was always that smell that reminded me so much of the old man. Time passed and, as an artist, I am invited to a smokers club, El Balcón del Habano. A monthly pairing was made there with different brands of tobacco and rum. I made many friends in that environment; some, the greatest experts on the subject. And I started studying that fascinating world.”

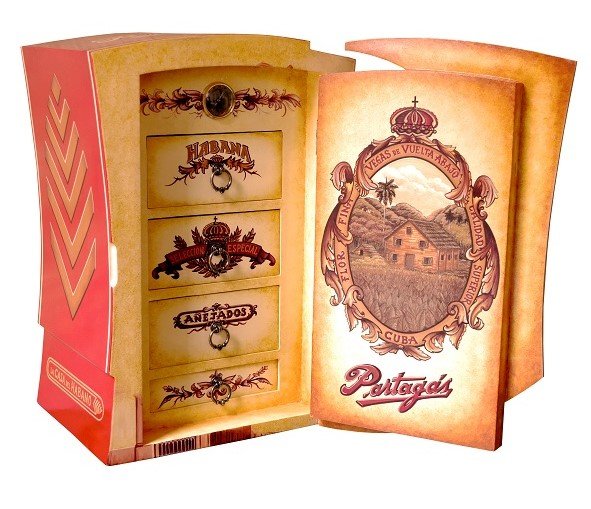

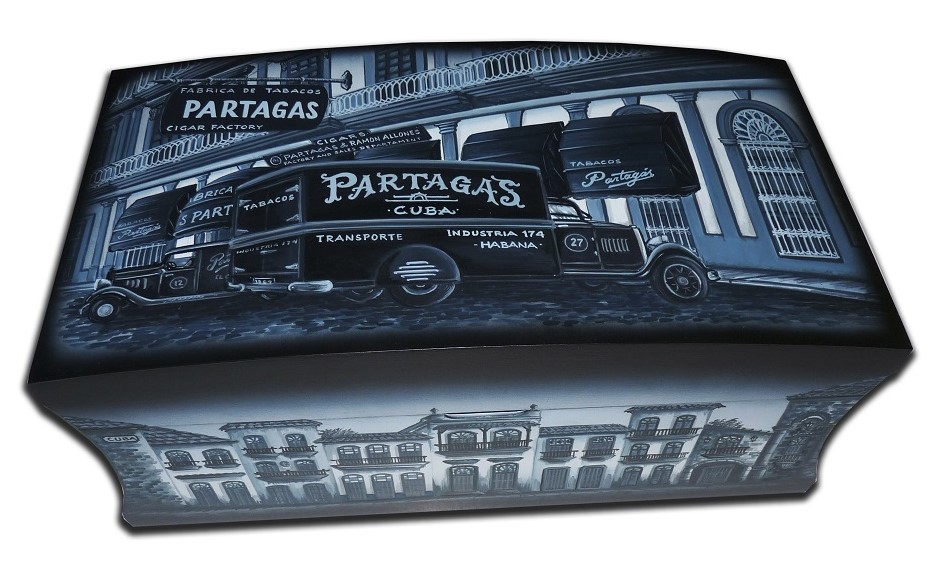

“I was interested — and still am — in the art behind the cigar. And I was captivated. Thus, I began to decorate some little boxes to give to those new friends, until one day Ángel Miranda, director of the Sikerei project, stumbled upon one. He told me: ‘I love it. Could you paint me a humidor?’ I accepted, but I didn’t know that he wanted to exhibit it at the Partagás Festival, for which there were only four days left. They were feverish and happy days in which I literally did not sleep. I delivered on time, the piece was exhibited, and it sold immediately.

“That’s how the challenge was born. A challenge, yes, because those who acquire this furniture are, in general, cultured, sensitive people, who want a beautiful object that does not fail to fulfill the function for which it was created: optimally preserving cigars. A humidor is not a painting, it is a three-dimensional piece of furniture that must be turned into a work of art. Historically, they were always sober and elegant wooden furniture, with different shapes and even inlays. Already being intervened by an artist, there is a big risk, and that is that in the end, it is a decorative piece of furniture, that expresses status, a pride, and inside treasures the most precious thing of its owner, the cigars. The danger is that the artist tries to impose what is characteristic of his work on the piece of furniture when what is desirable and wonderful is to surrender to the humidor, connect with it, know what it is going to represent, and honor the content it will contain. He must express in some way the pleasure of tasting a good cigar. The humidor is as important as the tobacco leaf drying house in the field; therefore, turning this object into a support for art means harmoniously concatenating its five faces, and even the interior. Not easy.”

“A painted humidor does not represent, in itself, the artist’s work, but rather the artist’s feeling towards the cigar, the spirit that emanates from each cigar with its aroma. It is respect and pride for the tradition of the many smokers who have been, and the affection and admiration for those old lithography artists who adorned the brands of the best tobacco in the world.

“I enjoy the decoration of each humidor. When I finish it, I sit down with it and smoke a cigar, accompanied by a good añejo. In silence we say goodbye. I know that it will go far away, but I also know that its owner will take good care of it and that it will pass from generation to generation of smokers.”

The humidors

I have not been able to find the exact information. It escapes me when the first of these beautiful pieces of furniture was created. I suppose it must have been due to some artisan in a European country, because there, due to the dry climate, the tobacco quickly loses its properties.

Humidors or humidifiers — which can be called all of these things — are commonly made of mahogany, ocum, or cedar. They are usually equipped with a hygrometer — to measure the degree of humidity inside — and a thermometer. Its function is to prevent the cigars from drying out (which is why distilled water is usually supplied to the rechargeable humidification system), to preserve it from insect attack and to preserve its aroma.

For optimal storage of tobacco inside humidors, humidity should range, according to experts, between 65 and 72%, and the temperature should not be below 16 or above 18 degrees Celsius. Under such conditions, it is stated that tobacco can maintain its qualities indefinitely, but other experts on the subject set the storage limit at five years.

In Cuba, two international events are held every year that focus on promoting the best tobacco in the world. These are the Habano Festival, which in 2024 will take place from February 23 to March 2, and the Friends of Partagás Festival, which traditionally occurs in November.

In both, premium humidors illuminated by Adrián Cuba are usually displayed; they can also be found, along with those decorated by other figures of national art, such as Roberto González and Zaida del Río, in Sikerei Art Gallery, Galiano 191, Havana, headquarters of the Ángel Miranda project, who provides these artists with such furniture, useful as well as beautiful.