Javier Sotomayor told us to meet for a talk at his bar 2.45, located a few meters from the centrally located Havana 5th Avenue, in Miramar. He arrives at the place running and somewhat late, he carries in his right hand two hangers with impeccably ironed shirts. He will wear them in the interviews that he has scheduled for the afternoon of April 3.

His image commands respect, no matter how many times you’ve seen him before. At 56, he maintains the slender and elegant figure that walked on the world’s tracks, jumping higher than anyone else just with the momentum of his feet. However, Sotomayor is very jovial, very approachable; someone who has not opted to hide behind fame or an important figure.

In his bar the bars are deserted due to a temporary closure for about a month. Almost all the lights are off, but the man from Matanzas moves with the agility and rhythm of the best dancer, dodging seats and tables until he reaches a brightly lit set full of cameras that a Puerto Rican journalist has set up to record a talk with him. There, as if in the center of the universe and with the recurring 2.45 in the background, he sits down to tell the story of his life for the umpteenth time.

From a distance, I hear them ask him why he didn’t jump more than 2.45 meters in his career. It’s one of the doubts that most plague sports fans and specialists. Sotomayor responds, to our surprise, that he probably didn’t go beyond the mythical mark because he stalled.

If we look at it with a cold eye, maybe he is right. He could not continue improving his records and became “paralyzed” in a world record that will be 31 years old in three months. Of all the possible ways to get stuck, this would be my favorite. But that’s how a man who had competitive ambition as his premise and who adapted to challenging and moving human limits thinks.

But was it the hunger for success that led him to be superior to the rest when it comes to high jump? Already sitting face to face, Sotomayor confesses to me that, honestly, the key to his success lay in taking advantage of his virtues, exploiting them to the maximum, to the point of making his deficiencies disappear.

“In the high jump, we have been using the same technique for quite some time, the Fosbury Flop, in honor of the American Dick Fosbury, who won the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico and introduced there the way of jumping that we all know today. But everyone has different styles of that technique. For example, from my time, I can identify who was jumping just by seeing the silhouette in a photograph, because each one had very specific positions.

“From a technical point of view, in theory I was not the best, in practice I was. Looking back, I think I should have worked on some deficiencies, such as the push-up over the bar. To correct that, I pushed myself with my hip and tried to go higher; but it was not optimal. I did focus on exploiting strength, power and speed, which were my greatest virtues, along with psychological and mental preparation,” explains Sotomayor with the patience of a teacher who seeks to capture the attention of his students.

From his response, a dialogue that is as long as it’s hurried is triggered, in which he travels from Havana to Salamanca, passing through San Juan, Barcelona, Atlanta, Sydney, Winnipeg, London, Tenerife or any other destination that saw him float over the rod 2.40 meters from the ground, as if it was the easiest thing to do.

Monologue

“I was afraid of heights, yes, it’s true; but then it went away. Otherwise, I would never have jumped so high. When I started in the sport as a child, I was not able to stand on a bridge and look down; or in a tall building. In my beginnings in Limonar, I stopped before any attempt. Well, they even kicked me out of the special area where I trained there, behind the Antonio Maceo school.

“I did my first jump in an elimination to qualify for the provincial pioneer championship that was going to take place in Varadero. I think that’s what motivated me to jump. In that event I took second place, I reached 1.44 meters at the age of 10 and they recruited me for the EIDE (the extinct Sports Initiation Schools). There they put you in one modality or another depending on the aptitudes they saw in you. In my case, I was skinny and tall and they sent me to a jumping coach, even though I had to do combined events. I immediately realized that they wanted me to specialize in high jump and then I wanted to leave school.

“But my family, especially my grandfather, talked to me, they told me that the coaches are the ones who know and they more or less convinced me; although I continued jumping almost out of obligation, because it was part of the pioneer pentathlon. What happened is that without trying so hard, without having that passion for jumping, I saw that I was winning the competitions in my category with some ease. At 14 I already reached 2 meters and if I hadn’t been afraid, I would surely have jumped a little more.

“What I liked were races and hurdles, although they were not practiced in those junior categories. I also liked the distance race and the triple jump better. At 13 or 14 I enjoyed that much more than the high jump.

“Yes, I was passionate about sports and I think that is fundamental. Since I was 10 I kept writings and notebooks with notes, step by step, of my first results in Varadero, in Colón, when I didn’t even come to Havana to compete. I had clippings from LPV magazines, I would buy two or three to keep the things that interested me and I didn’t miss any televised events. I didn’t like jumping because I was afraid of heights, but I was a fan of everything else.

“I would tell the kids now that the most important thing is to feel passion for the sport. There are people who have started in one discipline and ended up in another: Alberto Juantorena was in basketball and then went to athletics; (Omar) Linares, despite being from a baseball family, started in athletics. But I don’t think there are a majority of those who have come to excel in high performance without having a passion for sports.

“I have passed that on to my son Jaxier, who enjoys what he does. I think he is on the right track. He is pressured because people make a lot of comparisons with me. The DNA is there, he has my blood; but that doesn’t mean he’s going to be a world record holder. What more would I want! Now, if he continues jumping the way he is, if he continues to improve physically and mentally, I think he can compete at the highest level and reach the Olympic Games. It’s a more real possibility than the record, although you never know what is going to happen.”

Havana-Salamanca-San Juan-Salamanca: 40 years of record

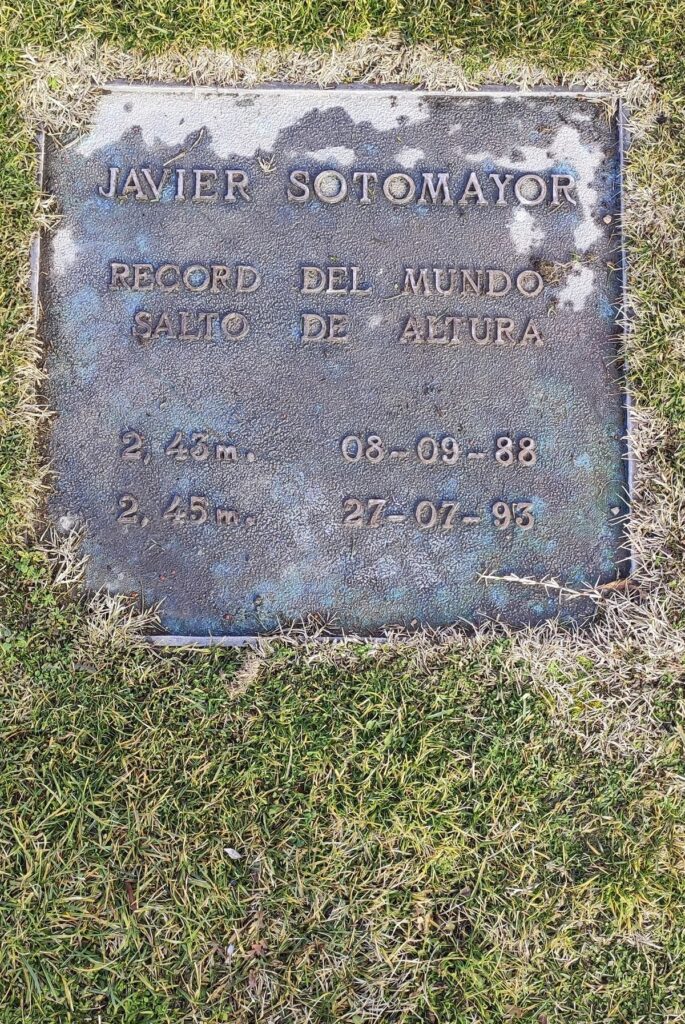

In the Helmántico tracks there is a plaque embedded in the ground. Besieged by grass, chastised by the sun and bathed by the scarce rains that fall each year in Salamanca, Spain, the piece of iron seems condemned to be eternally taking root in the earth, at least as long as the stadium named after Javier Sotomayor exists.

The plaque bears the name of the man from Matanzas and the reference to the two world records he achieved in that setting: 2.43 meters on September 8, 1988 and 2.45 meters on July 27, 1993. Sotomayor has a very special feeling for that venue and believes that his presence there was a play of destiny; although he does not hide that his Salamanca marks fell due to a somewhat fortuitous matter.

“When they talk to me about Salamanca my mind is transported to those times, the year 88, the year 93, the two world records. However, I can’t say that it has anything different from other places. In fact, if we had gone to the Seoul Olympics, perhaps the first record would have fallen there, and if it had not rained in London in 93, my jump of 2.45 would have been in London and not in Salamanca,” Sotomayor says shortly after observing a photo of the plaque in the Helmántico tracks.

And indeed, his still-current world record was achieved in the Spanish city just four days after jumping 2.40 in London, in a wet competition, his fiercest rival. “I couldn’t stand it, it was the worst in the world with a wet track,” he revealed to me once more than ten years ago.

In 1988, for his part, he decided to go to the event in Salamanca, which was held nine days before the opening of the Seoul Olympic Games, in which Cuba did not participate as part of the boycott with North Korea. If the Cuban delegation had gone to the Asian city, Sotomayor would have reserved himself for that event.

Either way, it’s irrefutable that his dominion completely transcends a city. The clearest proof is that he jumped 2.40 or more in Bogotá, Havana, London, Toronto, Seville, Budapest or San Juan, in Puerto Rico, where in 1989 he established his second world record (2.44). That record, however, goes somewhat unnoticed between his first record and the current one, perhaps because it occurred in a half-empty stadium after 9 pm on Puerto Rican soil.

“We were looking for that record at the end of a day at the Central American and Caribbean Athletics Championships. Almost the entire audience had left because the competition was decided and there wasn’t much else, but we tried and it worked. The craziest thing about that day was that the people from the delegation ran to congratulate me and pick me up and almost knocked the rod over. If that had happened, the record would not have been valid,” says Sotomayor, who will celebrate a total of 40 years as the world record holder in 2024.

In case the numbers do not add up for the reader, we are taking as a reference the first world record of the “Prince of Heights” still in force, which he achieved in the cadet category on May 19, 1984. That day, in Havana, he defied logic and jumped 2.33 meters at 16 years and 219 days old. Today no teenager comes close to that mark.

“Absolutely, that cadet record is harder to break than 2.45. Today, 2.33 is not reached in many senior competitions and the records of the world’s leading jumpers range between 2.36 and 2.38. In other words, there is no debate.”

The relay

Since May 4, 2018, no jumper in the world has managed to overcome a rod located 2.40 meters from the ground. That day, at the Suhaim bin Hamad Stadium in Doha, the Qatari Mutaz Essa Barshim was the last to achieve it and closed a chapter of several years in which he dominated the specialty with outstanding and stable records.

To give you an idea, of the 58 jumps above 2.40 that appear in the World Athletics books, 34 are distributed between Javier Sotomayor (21) and Barshim (13). Those closest to them are the Ukrainian Bohdan Bondarenko and the Swede Patrik Sjöberg with 7 and 4 marks at that height, respectively.

But those seem like distant times. The high-jump panorama has changed noticeably from 2019 to date, a period in which it has not even reached 2.39. “Bondarenko is no longer jumping and Barshim is still competing, but I can’t say that he is going to achieve great marks again. Everything is possible; it’s true that in this discipline there are very few jumpers who make their best records when they are 33 or 34 years old. There have been, but they are few.

“Among the rest, I think the Italian (Gianmarco) Tamberi has had very good results. His greatest virtue is that he responds when it’s necessary to rise to the challenge, but I can’t tell you that he is going to jump 2.46 either. It’s the same with (JuVaughn) Harrison or the Korean (Sanghyeok Woo), who can master the height between 2.35 and 2.40, but not go further.”

Cuba does not escape stagnation, although the phenomenon on the island dates back much longer and is influenced by different factors, just as Sotomayor explains: “If you don’t have an adequate mat you run the risk of leaving with a major injury.”

The places in Cuba that have mats are in very bad condition. Jumping 1.50 and landing in a small space is not the same as jumping 2 meters or 2.20 and landing in that same small space because there are no larger mats or in better condition.

“This issue of material conditions has hit the jump, but it has benefited threefold, for example. Many people do not know that great Cuban triple jumpers, when they were schoolchildren, jumped high and very well. Some like Jordan Díaz or Yoandri Betanzos jumped more than 2 meters when they were very young, but not having the conditions they ran the risk of getting serious injuries and went triple.

“Something similar happens in the pole vault. We take bamboo poles to teach the children how to make entrances, but if when they grow up you don’t have the pole it’s impossible for there to be progression. In the end, you realize that with our conditions we can only reach a certain level, a certain height, but not beyond. The reality is that we have fallen a little behind.”

The Olympic route: Barcelona-Atlanta-Sydney

On January 14, 1988, Cuba announced that it would not participate in the Seoul Olympic Games. Manuel González Guerra, president of the Cuban Olympic Committee, alleged security problems for the island’s athletes and demanded that North Korea be considered co-host of the summer event along with the South Korean city.

These ideas were expressed in a letter that Fidel Castro sent to Juan Antonio Samaranch, president of the Olympic Committee, in which he said: “Moral principles are more important than the emotions of the Olympic Games and the gold medals that could be obtained. Even our primary school children understand that bullets, tear gas and massive repression of the people would not be the most healthy and honorable conditions for the Olympic Games.”

Although Cuba left a small window open to reverse the decision if the scenario changed, that never happened. In sports and regardless of any political controversy, the position of the Cuban government affected an entire generation of athletes who did not have the opportunity to compete at the highest level when they were at the zenith of their careers. Many of them had also missed the 1984 Los Angeles Games due to the island’s support for the boycott of the Soviet Union, which did return in Seoul along with the bloc of Eastern European countries.

Javier Sotomayor is one of those who could have participated in both Los Angeles and Seoul and won medals in both events, but his Olympic debut was delayed much more than he would have wanted.

Do you remember how you found out that Cuba would not participate in the Seoul Games?

I don’t remember exactly how. I know we were in Europe and were waiting for the final decision; in fact, we got to have the Olympic sportswear. I don’t remember who told me or how they told me, but it wasn’t good to hear that.

What went through your mind at that moment?

Imagine, I wasn’t going to participate just to participate. At first it was a shock and I was forever left wondering what would have happened if I had competed there.

Would you have been Olympic champion in 1988?

I think I had a chance of being a medalist in both 1984 and 1988, but much more so in the latter. It was one of those years when I was doing well. I won the Grand Prix circuit, what today is the Diamond League. I was in incredible shape around the time of the Olympics. I cannot categorically say that I would have won, but the statistics of the time reflect that I had a real chance of being an Olympic champion.

Likewise, in 1984 I jumped 2.33, the cadet world record, and that was the height that the silver medalist achieved in Los Angeles, and the bronze was 2.31. In other words, skipping what I had already done, I could have been on the podium there too. I have two Olympic medals and maybe there could have been two more in my display case.

You were Olympic champion in Barcelona, a final in which four other men jumped the same as you. How do you remember that competition?

It wasn’t my best season, I think I maxed out at 2.36 a couple of times, because I had come out of an injury and was adapting to my new coach. More than anything, I played with the intention of winning, although I faced the competition with a lot of tension, perhaps the tensest of all. The night before I remember being awake and looking at the clock at 1, 2, 3…. The last time I looked was at 4 in the morning. At that moment I turned off the alarm clock and told myself that I was going to wake up at whatever time, without having breakfast or anything. That way I was able to sleep and rest well, and luckily the competition was late.

But it was very tense, because of what an Olympics represents, because of the fact of not having gone to the previous two, because of the desire to be Olympic champion, because eyes are also on me as champion and world record holder….

To make matters worse, I started with a zero at 2.24, which I later jumped 2.31 and 2.34 on the first attempt and the rest of the rivals had fouls at those heights, and that put me at an advantage. There I got motivated, I went to 2.37, I failed twice and asked for 2.39 because I wanted to make an Olympic record, but I was already alone and it was impossible to concentrate. It came to my mind: “I’m already an Olympic champion.”

In big events, the intention is to win, no matter the mark. If the competition requires you to set a record to win, then it’s done, but it’s not usual. In Barcelona I don’t think I was going to jump much more than 2.34 because it wasn’t my season, but it wasn’t the season or day of any of my rivals either.

After the success in Barcelona comes the disaster in Atlanta. Would you like to erase your 1996 Olympic memories?

No. These are things that happen to any athlete. I was coming off a good season, I hadn’t lost any competition, I even won a pre-Olympic competition right there in Atlanta. But I was suffering from a knee injury. I arrived at competitions, jumped, won and stopped. I didn’t make another attempt. Then I had to return from Atlanta, be treated at the Frank País hospital and have a small surgery on my knee.

It was minimal access, but I spent two weeks without doing any type of exercise and it was very close to the Games. Everyone who knows about sports preparation understands what it means to stop completely before a competition and then try to get back into shape.

I jumped only 2.29 in qualification. I didn’t play a good role, it wasn’t my best moment; but I’m not saying that it should be erased either because these are things that happen to any athlete, especially when one has been in the elite for a long time. Maybe someone who is four or five can be saved from a serious injury, but when you are in your twenties, something happens to you.

What experience can an athlete at your level gain after not meeting expectations?

I felt bad and, if I learned anything, it was that I shouldn’t have participated if I wasn’t at my best.

Given everything that has happened since the Pan American Games in Winnipeg and the doping accusations, how much value do you give to the Sydney Olympic subtitle?

That was another of the competitions that I experienced very tense, not only at that time, but everything that happened before. The first thing is I spent a year, or more than a year, waiting for the IAAF’s approval to participate in the Olympic Games. That permission came on August 4, 2000. In total, there were more than 12 months without jumping in any event. I went to the stadium every day to train alone, because my teammates were on tour in Europe, and without knowing if I was going to jump or not in Sydney. Preparing under those conditions, without certainty of what they were going to decide, was hard. I told myself: “If they analyze the case well, if they study all the evidence we provide, which shows that I am innocent, they will give me authorization.” Luckily that was the case and I was able to jump.

But well, it was a tense moment, especially after the competition. I had never done a drug test like that day in my life. I felt tense, maybe whoever saw me thought I was hiding something, but I was afraid that everything I had experienced in Winnipeg would be repeated.

It was a silver medal that, at first, I did not accept as a great triumph, like others achieved before. Not all athletes are as ambitious as me. Later, seeing the conditions and the way I went to those Olympic Games, I did understand that it was meritorious.

Your name appears in many of the world’s marks; however, the Olympic record has been held by the American Charles Austin (2.39) since Atlanta 1996. Do you have the feeling that this is a debt that is left to you?

I would have wanted to break the record, that’s the reality, but I don’t think it’s the main objective of the athletes in events such as the high jump or the pole vault. The dynamics of competitions are different and you outline the strategy to win, not to break a record. I did a first jump to secure a mark, in the second I tried to get a medal and in the third I tried to start playing with the gold.

In the races, the long distance, the triple or the throws, it’s more likely there will be great records in these events because the athletes achieve a real mark. The runner stops the stopwatch at a specific time, the javelin, hammer or shot put lands at a specific point and the same with long jumpers and triple jumpers. We do not. For example, when I won with 2.34 in Barcelona, you can see in the photo that I jumped much more, but what counts is where the rod is.

In these modalities one can do the best of one’s life, achieve the technically perfect jump, deploy the greatest power, get 20 centimeters off the rod, but that is not what counts.

Doping

“The International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) has confirmed the positive result for nandrolone of the Cuban athlete Javier Sotomayor, world record holder in high jump, at the Tenerife meeting on July 14, for which he will be suspended in perpetuity despite being already retired from the competition.”

This is how the newspaper AS opened a press release dated January 2002, which stated that the Cuban had tested positive in the two urine samples with levels well above the established limits. In this way, the career of the best high jumper in the history of athletics ended definitively.

What is the story behind this doping case?

It’s a positive that I never understood, because I had out-of-competition tests done before and after that event in Tenerife and nothing was detected, even though nandrolone is a substance that remains in the blood for a long time. But well, I was the only one who was tested in Tenerife, at random, and it fell on me.

Perhaps it would have been avoided if you retired after the Sydney Olympics, also taking into account the injuries and chronic pain you suffered. Why not end your career there?

I left the Games practically without injuries. By not having such a great intensity, I stayed healthy. That’s why I decide to continue; but the following year, when I started really grinding, my knees and ankles couldn’t take it anymore. I was about to turn 34 and was not winning, so I announced my retirement in October 2001.

Do you feel that in some way those two controversial doping accusations called into question the main achievements of your career?

There are always malicious people, but I don’t think it has influenced my legacy or the way many assess me today. When you sit down with all the evidence in hand and look at the circumstances in which the two doping cases occurred, you have to question at least a few things.

For example, in Winnipeg 1999 the doctors told me not to jump because I had a hernia, but I decided I would and obviously I was going to win, so I was aware that I would go through an anti-doping control. Consuming something prohibited was taking an absurd risk. It’s like going to rob a bank with a thousand police inside. You’d have to be the dumbest person in the world.

The thing is that when all that scandal broke out, we lacked the experience to handle the situation. First, I tested positive in test A with levels of cocaine that would not only have prevented me from competing, but would have killed me. In test B I tested negative. Everything should have ended there, but we accepted a C test that had never been done, that does not exist in anti-doping controls. That was the mistake.

But in the end we provided all the evidence that led the Olympic Committee to lift my sanction to compete in Sydney 2000.

Do you regret anything or would you change anything about your career?

There are things that could be improved. As they say, if I’m born again tomorrow maybe I’ll do things I didn’t do, or vice versa. In life you can always correct something.

The present’s jumps

He hasn’t stood in front of the bar to fly over it for many years, but Javier Sotomayor has multiplied his notoriety over time. Away from the tracks, “The Prince of Heights” has become an icon of Cuban sports and one of the most recognized figures globally. We can frequently see him as a guest of honor at events in Budapest, Tokyo or Paris, or receiving awards in Barcelona, Madrid or Miami.

“I couldn’t be more grateful for all the recognition, for the way the fans remember my marks and my victories. I like to think that they are the ones who have really kept the records and titles alive,” says Sotomayor, standing, almost ready to take off after approximately an hour of dialogue.

His influence today, like his jumping power yesterday, knows no limits, and he has taken advantage of it to serve as a leader and example for the new generations: “I feel good when I pass on my experiences to high jumpers, mainly from Cuba. Perhaps by coincidence, the best results of many of them have been with me present and I am glad that my advice has been of some use to them, although what they have achieved has not depended only on me. I have never been a full-time coach, not even of my son, who I am working with now; but I carry out that role of guiding the younger ones well.”

Although not as tense as in his days as an active athlete, he lives with much more pressure than we can imagine. He is a man who has achieved everything, but he has goals and dreams left to fulfill. One of his greatest short-term desires is to organize a new edition of the José Godoy In Memoriam Jumping Festival, in honor of his first great coach.

“It’s a competition that has been going on for several years, we only stopped due to the pandemic and now we are going for the ninth edition. This year we intend to do it indoors if I can get help from MONDO. The intention is to do it at the Ciudad Deportiva Coliseum, with a great cultural show. We want to bring together many people; among them, the best jumpers in the country in different categories. Before we have mainly had athletes from the capital, but we want many more to come from other provinces,” says Sotomayor, who also spends his days as an entrepreneur.

“It’s a complicated topic,” he says and smiles, perhaps a little nervously. “The most difficult thing is finding the time to dedicate to my business. I must also learn so that things that are happening to me do not happen to me. There are blows that teach you. To be a better entrepreneur, I think we must all prepare ourselves better to get ahead.”

Being away from his son Jaxier is another of the challenges he faces. “Unfortunately, we are not together full time, I think that is something that has slowed him down a bit. It’s not positive for a 16-year-old boy to train alone for six months or more,” says Sotomayor, who barely has time left until leaving for a new commitment.

Before leaving through the door, one last question that the photographers who accompanied me, Ricardo López and Jorge Luis Coll, wanted to ask him since 2 in the afternoon: Did Sotomayor ever jump more than 2.45? “I didn’t even try: jumping more than 2.45 is crazy.”