“I was born in a broken country,” says Greta Reyna (Havana, 1991). “Much of what is beautiful within it is broken, disguised as conformity and inventiveness.

“Almost all my work is born from broken objects, those that have lost their original function, those that have been abandoned due to the lack of capacity for renewal. I am interested in that happy encounter that is established between the beauty of these forms and their broken nature.

“Each gesture of collecting these broken objects is linked to a ritual practice inherited from my maternal grandfather, and to my personal experience as a social being in a context in which, due to precariousness and material needs, recycling and reuse are part of everyday survival.

“Chance, mixed with an almost unconscious search for these objects and events, transforms everyday procedures into a staging of installations, paintings, environments and stop motions that end up giving them a “useful” life within the art world. Everything I do becomes an optimistic search for the conciliation of the human being with his environment.”

She, an ISA graduate, with a master’s degree in graphic design and multimedia, has set out to repair the world. If not everything, at least her emotional world, made of the friction and mediations between human beings, but also of tiny forgotten objects that were useful or beautiful, that accompanied us for a stretch of our life, and that are discarded. Greta reacts against expiration, calculated or not; she believes that things have more than one life.

And that’s what she goes for, collecting, classifying, rearranging the fragments with aesthetic intention: saving. She believes in the healing power of art and in the role of the artist as a social motivator.

She has her workshop in a quiet house in El Vedado, with walls that preserve the wallpaper from the 1950s. There she exhibits part of the work; and she accumulates her “findings.” I suppose that when the artist is not there, those little beings come to life and get up to their usual old tricks. I also suppose that this pugnacious energy is what she will later give to her work.

You quote your maternal grandfather in a text and relate it to the practice of collecting broken objects.

Shortly after my grandfather’s death, I took an old glass bottle that we had at home, raised it to the roof with a funnel, and left it there for days, waiting for it to fill with rain. I recorded a phrase: “Yesterday the sky cried just like I did.” It still has the water from fourteen years ago.

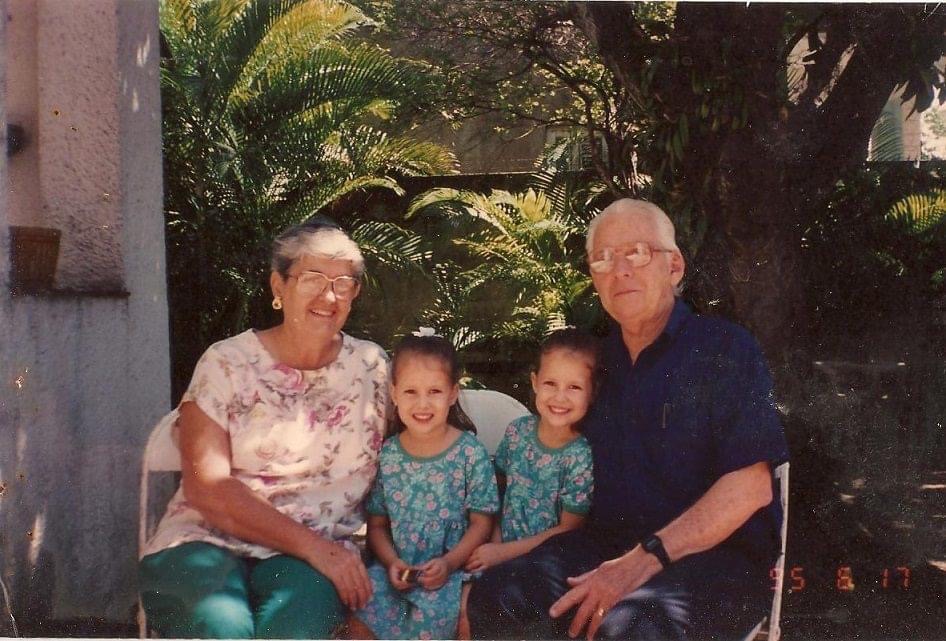

On Christmas 1995 my grandfather hung a pantyhose from the hall lamp; inside he put a box lined with wrapping paper, which contained other boxes inside. The last one contained a plastic doll that my aunt, pregnant at the time, had always liked. He bought it for my unborn cousin. It was quite an event!

My work methodology has a lot to do with the way he created and installed, each object or action had a story behind it. The same thing happens to me; I find objects and build scenes, some more intentional, and others arising by chance. I owe to him much of my sensoriality towards objects in a space.

It’s the reason I always mention him, it’s the way I keep him alive.

Can you refer to the procedure for creating your videos? Do they have the generic name of “Alma”?

Stop motions emerge from a moment of external inactivity, such as COVID-19. I needed to create, do something that would keep my creativity awake. I decided to give soul (hence the title of the series) to those many objects that I have saved.

Carrying out this type of work requires a lot of patience and order, something that I am very good at, and that I enjoy.

In this series of random micro stories, in which I do not create a prior script, I choose the objects that I think have something to tell, and I begin to recreate tiny scenes inside closets, sinks, corners and spots.

Do you do them entirely or do you get help from other professionals?

I do everything alone, from the execution of movements, to photography, editing and music. For the design of the soundtrack, I have had the collaboration of Adonis Ferro.

What can you express through videos that you can’t achieve with installations and two-dimensional works?

The installation and two-dimensional work have something in common with the video work: the refunctionality of the object and its subjectivity. Neither of the two ways of doing things pretends to have a direct discourse, I am interested in the holistic nature of the dissimilar interpretations. In that sense, each one has its own nature, without singling out one over the other. Let’s say the movement is the most notable difference. Only within stop motion can the broken objects I use interact in motion.

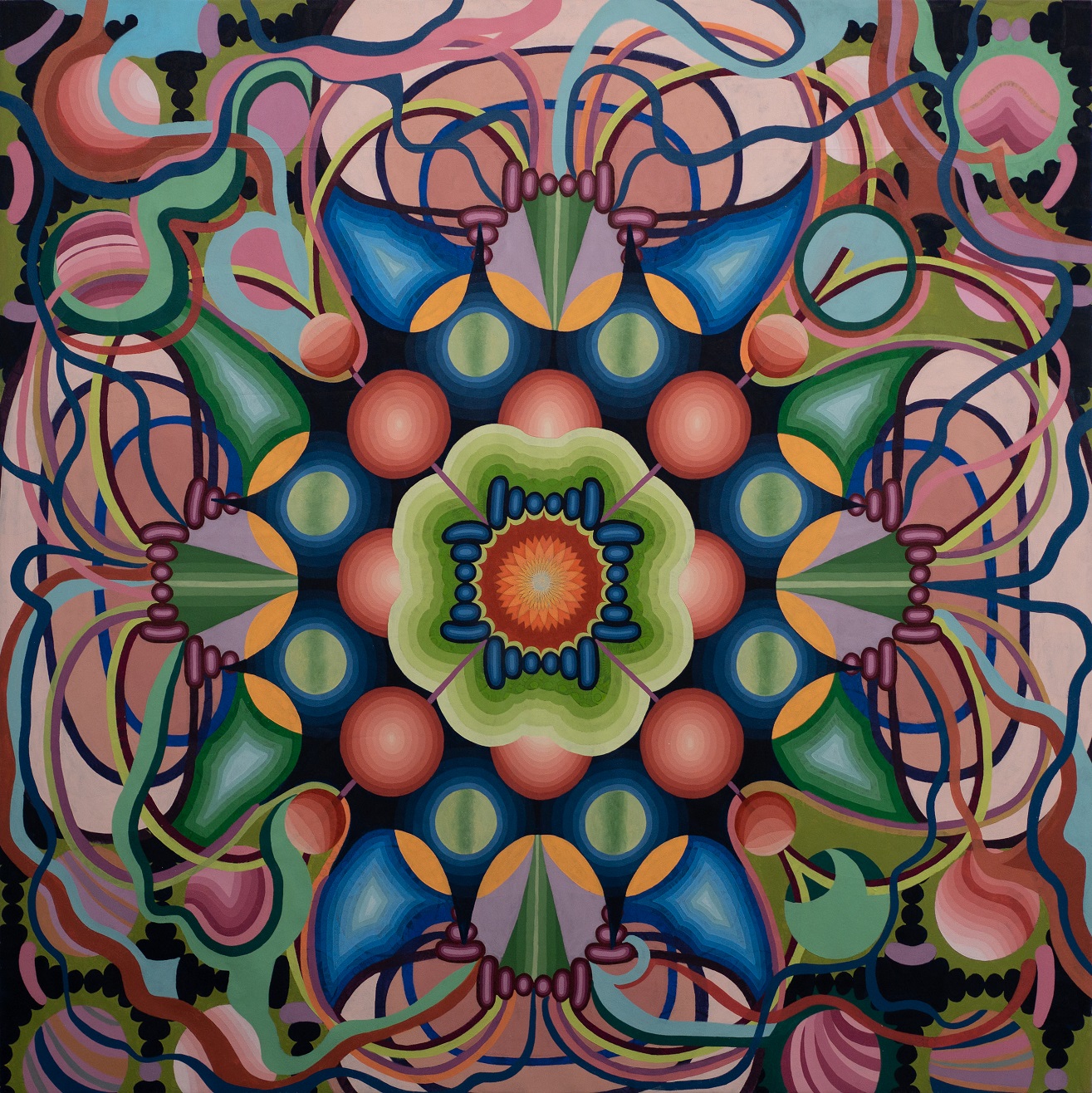

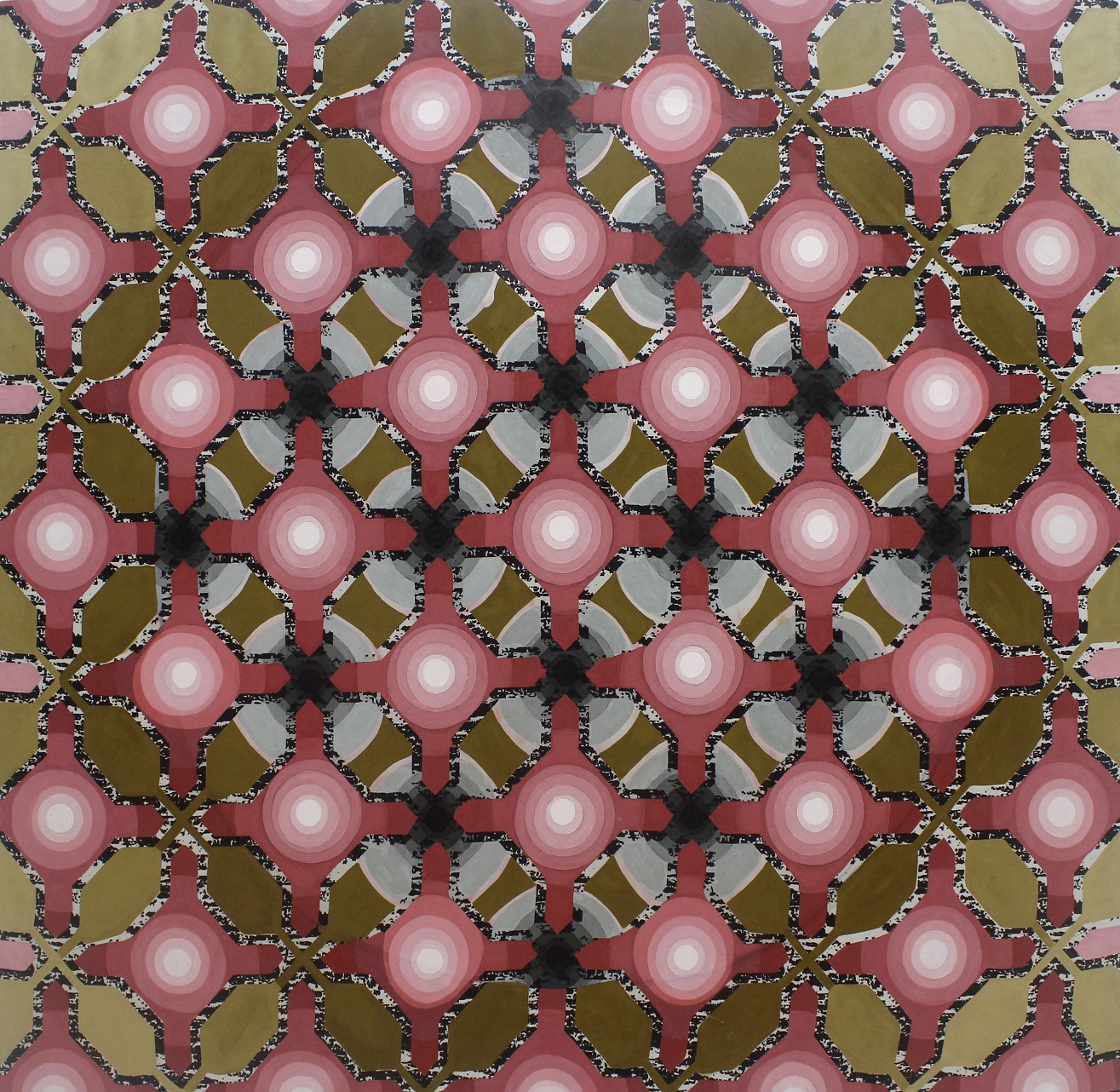

How much abstraction is there in your work?

I consider myself an artist who works, for the time being, within abstraction in its broadest sense. Many times, when I try to draw something of the natural, I end up doodling. When I think about the conception of my pieces, I never imagine the figure. I turn the objects that allude to certain everyday symbols into abstractions; even stop motion, which are the ones that could come closest to figuration, have an abstract base.

Do you intend to create an intellectual or emotional bond with the viewer?

I try to provoke in the other a reflection on how we are consuming objects, and in what way we assume domestic spaces.

Are the series of drawings Interior roto (1 to 6) sketches for possible installations or “surveys” of existing places?

Both things: possible installations, environments and surveys of real and/or imaginary spaces. In fact, “Interior roto #2” arose while I was drawing the sketch of how one of my pieces would later be installed.

You say that you were born in “a broken country…disguised as conformity.” Can you elaborate on that statement?

I was born in a broken, but beautiful country. In my opinion, Cuba is one of those magical places that captivates you, not only because of its light or nature, but also because of its vitality, despite the complex circumstances we are going through. Human quality and that capacity for reinvention makes us Cubans very resilient.

In your statement you talk about “an optimistic search.” Do you believe in the transformative power of art, in its role in the process of growth of human beings and, therefore, of society? Don’t you ever doubt those qualities? Don’t you get discouraged sometimes?

I believe in the power that artists have to develop actions that lead a change in society. I know stories of people who, thanks to this, have been saved from marginality; others have to find that space of freedom in which they can express themselves. I believe that art heals. Some of my pieces, like “Diario del dolor,” or the most recent, “Objeto roto #53,” helped me concentrate my strength and return to my center.

I’m going to mention five pieces. The idea is that you tell us the genesis of each one, both conceptually and factually. These are: “Objeto roto # 4,” “Paisaje para Hélio Oiticica,” “El salón de espejos,” “Amantes” and “La torre.”

“Paisaje para Hélio Oiticica” was a piece that I made in the third year of ISA for the project of professor Julia Portela. Hélio Oiticica was one of the artists who influenced me the most during my career. I decided to create a landscape that included abstract elements that evoke events in nature, such as the night, the land, the sea…, interpreted based on pure color pigments contained in containers.

“Objeto roto #4” is one of the first paintings I made. I had a lot of respect for painting, and that inhibited me. The painting is possessive, it wants you all to itself, that you dedicate all your time to it. I avoided it so much that I decided to study engraving.

One day, Adonis Ferro, while looking at one of my drawings from the Interiores rotos series, told me: “You are going to be a painter at some point.”

Shortly after, I decided to face the challenge. With a few small format canvases and some of my broken objects as inspiration, I started painting.

The broken object in that piece was my grandmother’s baccarat vase, like many other objects that are hanging around in my collection until the day I get inspired and give them some aesthetic use.

“El salón de espejos” was my fifth stop motion. After a few weeks practicing the technique, I found a game of checkers performed by Inuit. It also had some small broken mirrors and other decorations. I gathered these elements and decided to start recreating a micro story that presents a ritual in which the Inuit, through a candle and a secret, end up invoking various figurines. I was never clear for what purpose; it just came about that way.

I made “Amantes” in my studio, in front of the wall paper printed with roses, from the 1950s. The protagonists are a horse and a sheep who are linked in a story that talks about accepting the other even when they seem to be broken. I think that we are imperfect beings and that beauty lies in that imperfection.

“La Torre” is my eighth stop motion, made in the closet of the house. This video is the longest I have made, and the most complex, not only technically but also conceptually, since it does not have a preconceived idea and everything becomes somewhat surreal. Perhaps deep down there is a brief love story based on various rituals; among them that of the mare woman, the legs of a horse and a sword, or the image of the tower and a pearl pendant.

These five pieces speak of my efforts to rediscover, from the broken, the beautiful. They also all represent a space of peace and delight.

I am writing a book of poetry whose working title is La segunda vida de las cosas; a topic that has a lot to do with what we have been talking about. There I deal, among other issues, with the recycling of feelings. Do you think it is possible to “reuse rather than throw away” feelings?

We human beings have feelings and emotions that go through an infinite scale of values. We can all suffer negative emotions that, if we do not learn to embrace to transmute them, it will be difficult to reuse those wounds for healing. There are two tools that help us achieve this: will and discipline. These two can lead you to become resilient. Resilience could be the reuse of emotions in order to strengthen ourselves through noble and sincere actions towards ourselves.

By distinguishing the objects through an artistic operation you give them another condition. Does creating a new function for objects make you feel, to some extent, like a demiurge?

I only feel like a demiurge in my personal life, in which my work is implicit. The greatest power that artistic practice gives me is self-knowledge and understanding of others. Objects are not organic matter, so they cannot heal themselves, they need a human to regain life. In that exchange I am healing a story and at the same time I am rebuilding myself with them.

I quote César Vallejo: “The point where a man passed, he is no longer alone. It is only alone, of human solitude, the place where no man has passed.” Some of your pieces refer me to that fragment. They are those works that are born from everyday objects that have expired. Are you trying to take away their loneliness?

Many of my objects belong to oblivion, the vast majority stopped working, they are broken. Once in the art world they are given some useful life, even if it is aesthetically, but they are also reborn in the sensations of each viewer when faced with them.

Are you familiar with kintsugi, that Japanese practice of repairing objects that does not attempt to conceal the site of the fracture, but rather to highlight it, even seeking to give it greater beauty? Is your work related to the philosophy of that procedure?

My work draws on kintsugi in terms of the idea they propose. In fact, I learned about this art after starting to work with the energy of the broken. I am interested, like them, in metaphorizing with the idea of embracing the wound and transmuting it, converting trauma into something of positive learning, and through it strengthening ourselves. It’s just what we were talking about, about reusing feelings and being resilient.

Can you briefly comment on your artistic genealogy, those artists from which your poetry begins, paradigms in Cuban and international art?

In the field of visual arts, I have several references. Among the Cubans would be Tatiana Mesa, Amelia Peláez, Carmen Herrera, Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, Loló Soldevilla, Pedro de Oraá, Sandú Darié, Salvador Corratgé and Mario Carreño.

On an international level, I feel close to Adriana Minoliti, Hilma af Klint, Beatriz Milhazes, Liliana Porter, Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró, David Hockney, Gabriel Rico and Abraham Cruz Villegas.

Gabriela is also a very outstanding artist. It is said that there is a special communication between twin sisters. Do you think that condition has decided the vocation of both?

Being twins did not determine that we both studied the same thing, the determination of this was to discover art together. It was something organic, when deciding there was no opposition or suspicion on the part of one or the other; on the contrary, we enjoyed sharing it.

Do you collaborate in your respective works?

We started working together. We have always been very respectful of our decisions together and separately. We give each other feedback all the time and we are very critical of each other. This helps us rethink ideas and bring them to fruition. For both of us, both our opinion of the works is extremely important.

In the exhibition Évame ― a title that, it seems to me, speaks of a certain gender militancy ― how do you think your works dialogue? Are each your poetics perfectly delineated?

Évame is the title of a poem by the Spanish Carlos Oroza. It would be something like turn me into a woman. For me it’s more like love me or fall in love with the woman I am. We enjoy being women, and we defend everything that entails based on a space of peace.

In the exhibition the works dialogue in a harmonious way and without hierarchies. Each one, from our own universe, converges in the same way that we do: two different and, at the same time, complementary poles that love each other above any circumstance.

Is this the first two-person project you have done?

Yes, and we feel satisfied with having managed to represent what we are as artists and sisters.

Will there be more exhibitions with this tendency?

We are always willing to collaborate, we are very good at it. So we are open to more projects to carry out together.