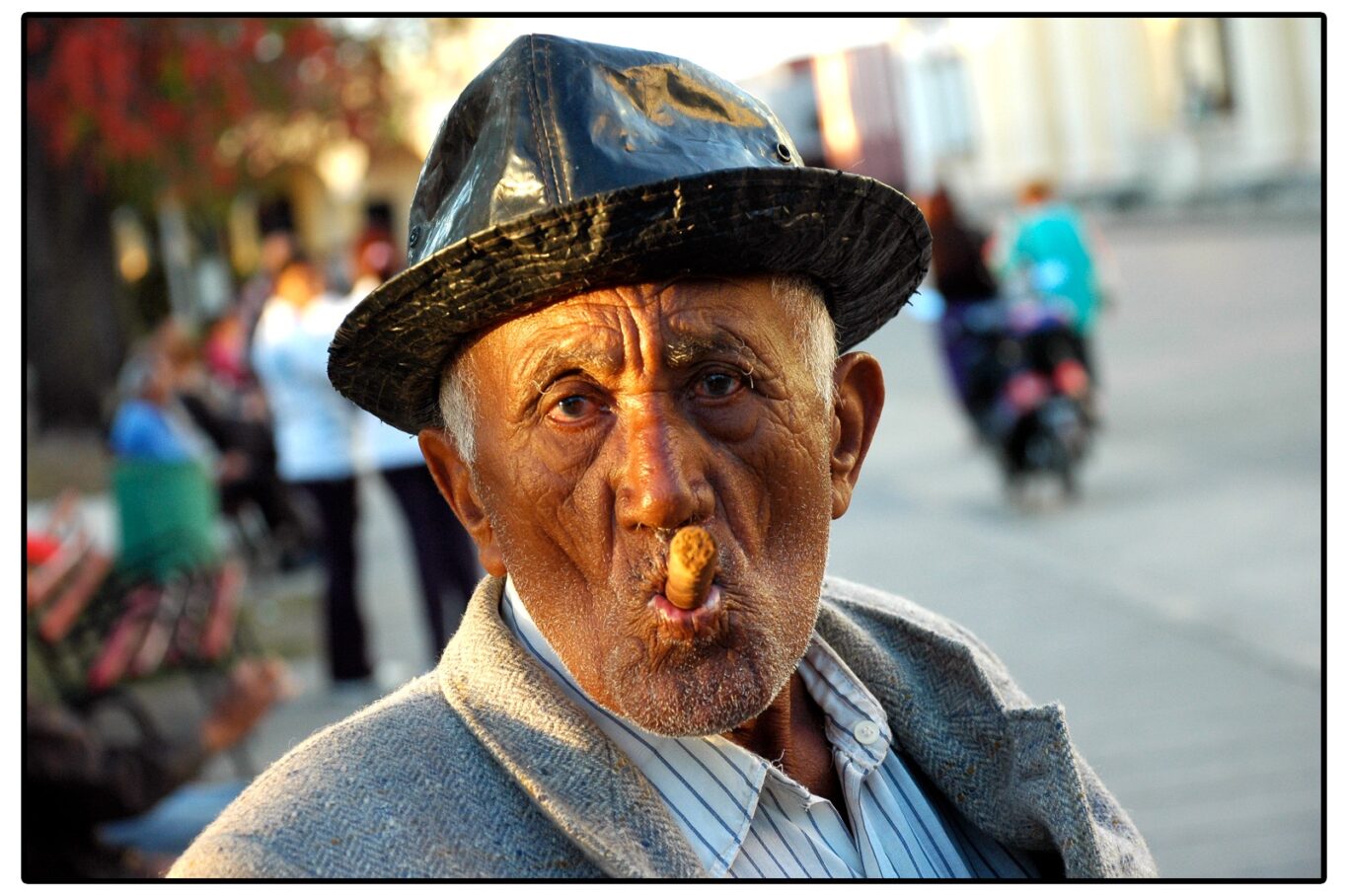

The liver did not kill him…

But the lung, where the cancer grew, they say, because of having smoked without rest.

And the truth is that I can barely remember him without a cigarette…

Even in the hospital, dying, he begged to be lit a cigarette.

Only a bit. Just for a bit.

And Fernández? Roberto Fernández Retamar

A few days ago I remembered, precisely when a neighbor passed by shouting that the cigarettes had arrived at the grocery, “And Fernández?” the heartbreaking poem that Roberto Fernández Retamar dedicated to his father.

It is contradictory that, in a country where there is an explicit interest in reducing the incidence of smoking, cigarettes and tobacco continue to be included among the products sold on the ration book.

According to the 2022 Demographic Yearbook, there are more than 8.7 million people over 20 years of age in the country, who have the right to buy 4 packs of cigarettes per month.

In this way, more than 35 million packs would be marketed at very low prices, which is equivalent to more than 700 million cigarettes every month. This is without counting what is sold freely in the increasingly extensive network of bars, cafes, kiosks and shops of all kinds.

It is worth asking then: is everything necessary being done to stop the nicotinic epidemic in Cuba?

Smoke-free generation

According to the latest WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 71% of the world’s population lives in countries where one of the six measures considered essential to limit the effects of this pandemic has been taken. However, some governments are taking even bolder decisions to prevent its escalation.

An example of this is the Tobacco and Vapes Bill, recently approved by the House of Commons of the English Parliament with the aim of creating “a smoke-free generation and tackling the problem of vaporizers,” according to a publication from the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Specifically, the law will criminalize the sale of tobacco products or their derivatives (which include cigarettes, nicotine-based substances, etc.) “to any person born after January 1, 2009,” according to an article published in Expansión.

The law has a peculiarity: while it is in force, each year the legal age allowed for the purchase of these products will be increased by one year. The goal is to avoid replacing one generation of smokers with another, giving young people “the freedom to live longer, healthier and more productive lives,” according to the law.

Scheduled to come into force on April 1 of next year, the law has a peculiarity: it will not penalize tobacco itself nor will it prevent anyone who can buy it today from doing so in the future, since according to Victoria Atkin, UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, the authorities are not seeking to “demonize people who smoke.” They seek to protect new generations from the harmful habit and help addicts quit smoking, doubling public funds dedicated to this.

Another issue included in the law is related to vaporizers (vapes), which are commonly known in our country as electronic cigarettes. According to an article published on the American Cancer Society website, these devices include a battery for ignition, a heat source that converts the liquid contained in the cartridge into “an aerosol of tiny particles.” This can be based on nicotine dissolved in oil and other products, such as Synthetic Cannabinoids, which we referred to in a recent work. Finally, they include a mouthpiece or opening to inhale the aerosol.

Vaping is becoming a serious problem in several European countries, which has even reached schools. According to the Expansión article, these products are sold at very low prices and share shelves with sweets and candy. To make this macabre sales strategy more effective, their labels contain cartoon characters and flavors are added to the nicotine-based compounds. Hence, the new law will also regulate everything related to flavors, packaging and the way in which vapes are displayed in stores, to prevent children from becoming addicted to nicotine in this way.

Some analysts believe that this law is inspired by a similar one that was approved in New Zealand, but was repealed practically before becoming effective, when the government of that country changed this year.

A pandemic among pandemics

The interest of the British in putting an end to smoking is, without a doubt, laudable, especially when the figures generated by this pandemic are known. According to the WHO, more than 8 million people die every year in the world from diseases related to smoking. Keep in mind that, according to the UN, the death toll from COVID-19 between 2020 and 2021 “only” would reach 14.9 million. This represents about 7.5 million deaths per year, 500,000 fewer than those who die from tobacco.

Additionally, the majority of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, such as Cuba. And the fact is that 8 out of 10 of the 1.3 billion tobacco consumers live in these countries, where the impact of this pandemic on morbidity and mortality is usually higher than other geographical areas.

According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), tobacco is “the only legal consumer product that kills up to half of its users when used exactly according to the manufacturer’s instructions.” Because? Because, according to the same source, companies spend an exorbitant figure of 8 billion dollars a year on marketing, which brings them enormous profits. Meanwhile, in terms of lost productivity and health expenses alone, the global cost of smoking is estimated at 1.4 trillion dollars, which represents almost 2% of the world’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

If we talk from a medical point of view, the life expectancy of smokers is on average 10 years less than that of non-smokers. But even these are not exempt from dangers, because exposure to others’ tobacco smoke causes, according to the WHO, 1.2 million deaths a year. Furthermore, nearly 1 in 2 children in the world breathe air contaminated by tobacco smoke and 65,000 children die as a result of this. The above represents half of the 110,000 deaths caused in children in 2019 by another terrible pandemic, HIV/AIDS.

The path of Bhutan

One might think that the solution is to completely ban the cigarette trade. This is what Bhutan did, a tiny kingdom of 700,000 inhabitants located in the Himalayan Mountain range, neighboring Nepal, India and China, where since 2005 a law was approved that sought to create a smoke-free nation.

However, by 2011 the measure had been very ineffective. And, instead of reducing consumption, it created a thriving black market, coming from India.

In an effort to stop this phenomenon, that year more than 50 people had been imprisoned for violating the severe customs regulations, which only allowed importing 200 cigarettes, as long as the bearer kept the receipt with the date of purchase.

One of the cases that attracted the most attention was that of a Buddhist monk who, for failing to keep the document and importing 74 packets of chewing tobacco, was imprisoned and sentenced to three years. The above caused an angry reaction on social networks in the Asian country, according to a DW report.

Regulatory policies, are they effective?

A milestone in the global fight against the tobacco pandemic was the adoption by more than 160 countries, including Cuba, in 2005, of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). This was the first international public health treaty sponsored by the WHO and containing guidelines for the implementation of tobacco control measures.

Among the key provisions of this document are the obligation to raise taxes on tobacco products (Art. 6) by the signatory states, who must also protect against exposure to others’ smoke in workplaces, closed public places and public transportation (Art. 8).

The agreement includes mandatory health warnings on packaging, which should cover at least 30% of the surface and, ideally, 50% (Art. 11). Finally, the advertising, promotion and sponsorship of tobacco products is prohibited, in accordance with article 13 of the regulation.

In addition to the FCTC-WHO, according to an article on legislation for the prevention and control of smoking in Cuba, there is a plan of WHO measures called MPOWER-WHO, which seeks to: monitor tobacco consumption (Monitor); protect people from tobacco smoke (Protect); offer help to addicts (Offer); inform and warn about the dangers of this addiction (Warn); prohibit tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (Enforce); and increase the price and taxes on tobacco (Raise).

These treaties and plans have had a great impact in various countries, including Ireland, Norway, Italy and Spain, where tobacco consumption in bars and restaurants is prohibited.

In our region, restrictions apply in countries such as Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Uruguay. In the latter, smoking is prohibited in closed public or private spaces, and fines for non-compliance range from a thousand dollars to the definitive closure of the establishments, according to the aforementioned publication.

Smoking in Cuba

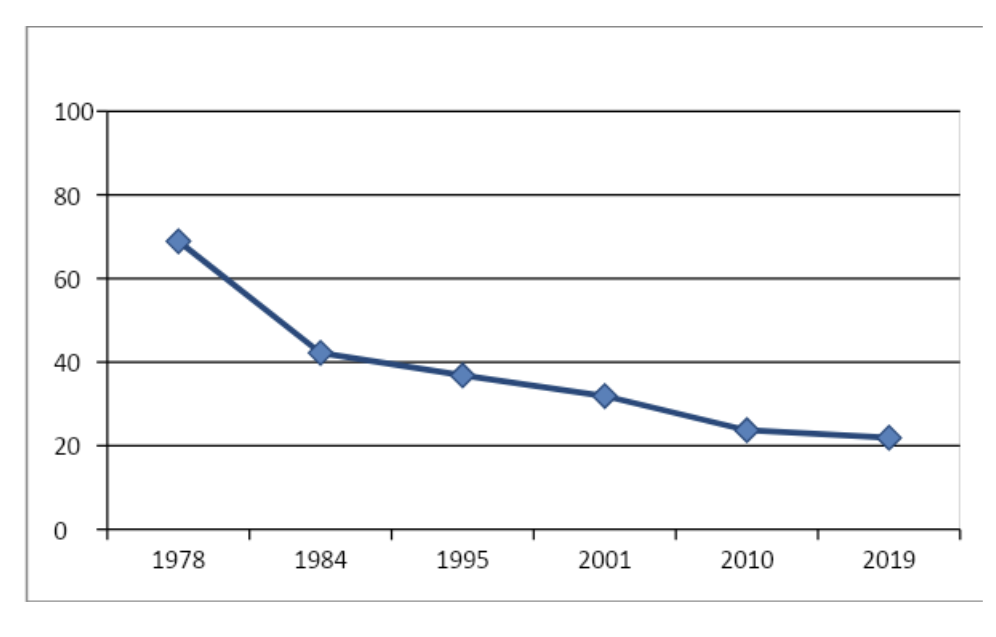

According to an article published in the Revista Cubana de Salud Pública, in the last fifty years the numbers of the tobacco epidemic in Cuba have been progressively decreasing. In 1978, the prevalence on the island was 68.9% for the population over 17 years of age. This ranked the country among the first places in the world, thus on that date a series of measures were taken.

By 1984, the prevalence of smoking had decreased to 42.2% and the per capita consumption of cigarettes annually was 2,470. Eleven years later, in 1995, 36.8% of the population smoked in Cuba, with a 48.1% prevalence among men and 26.3% among women.

In 2001, the prevalence had decreased to 31.9%, with nearly 2 million smokers. Additionally, cigarette consumption decreased to a per capita rate of 1,314.

By 2010, the prevalence of smoking on the island was 23.7% for the population over 15 years of age. Of that total, 74.8% began smoking before the age of 20, so the greatest prevention actions had to be directed toward that group.

Nine years later, the numbers had not changed significantly. According to the results of the latest smoking survey carried out on the island in 2019, 21.6% of the population was smokers, which is equivalent to more than 2 million people. The starting age of the harmful habit on the island is 17.4 years.

This shows, rather than slight progress, a stagnation with respect to what was achieved during the previous decade (Table 1). Another important fact is that 30% of Cubans are exposed to others’ smoke. In that sense there was progress compared to 2010, when the figure was 41%.

Need for a law

Although the incidence of smoking in Cuba has decreased in recent decades, there is still much to do. The island is far from nations such as Nauro or Burma, where 49.5% and 43% of the population smoke, respectively. But we are also far from showing results like those of El Salvador and Colombia, which show figures close to 8%.

In our country there are also the typical controversies of a producing nation: tobacco, in addition to being an important economic item, is a source of national pride and is strongly linked to traditions and identity.

As for legal instruments, it is not that there is an absence of them either. According to one of the articles already cited, from 1976 to 2017, 29 documents of different scope related to smoking were approved on the island. Five of them were approved by the National Assembly, two by the Executive Committee of the Council of Ministers and the rest by the Ministries of Public Health, Education and the Institute of Civil Aeronautics, among others.

However, the existence of the regulations does not guarantee their compliance. I don’t know a single person who has been fined for smoking in a public space. It is enough to get on a bus or go to any institution to see people, even officials, smoking peacefully.

Even in hospitals, the environment in which I work, and schools, I have seen people contaminating other people’s air with the smoke from their cigarettes; if someone calls them out, they respond angrily. We have reached that point, despite the multiple awareness campaigns that are launched.

All this occurs in a context where smoking causes more than 13,000 deaths a year, 36 Cubans die every day from this cause and, on average, a smoker consumes more than 15 cigarettes a day, while 45% of smokers have high dependence and starts smoking in the first five minutes of the day. All these data are undoubtedly scary and worrying.

It is evident that the country urgently needs a comprehensive anti-smoking law that regulates everything related to the monitoring, surveillance and control of this epidemic. As well as a willingness to implement it, despite how unpopular it may be.

In this way, it would be possible to combine in its single text, in an articulated and systematic way, all the measures included in the MPOWER-WHO plan, advancing those that have already been implemented and incorporating those that are missing. Furthermore, it would require joint action by all State agencies involved in this matter of vital importance to society. The lives of thousands of people are at risk.