A group of Latin American journalists, convened by Inquire First, a non-profit journalism organization based in San Diego, California, recently spent a week touring the border between the United States and Mexico. Photojournalist Kaloian Santos Cabrera, from OnCuba, was part of the group. The series “The border of the American dream” attempts to capture several of the intense experiences lived during those days in mid-July. Here is the first installment.

With 3,185 kilometers in length, the territorial border between Mexico and the United States is witness to a rich cultural and economic interaction, but also to complex challenges. It covers urban and inhospitable areas, from Brownsville, Texas, and Matamoros, Tamaulipas, on the Gulf of Mexico, to San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Baja California, on the Pacific.

The dividing line between the two countries was established more than a century ago with a line on a map. In 1845, during the U.S. expansion, Texas was annexed and, after winning the war with Mexico, the United States kept more than 55% of Mexican territory. The border was relocated to the Rio Grande (or Bravo), and included other natural barriers, such as mountains. Since then, the region has become a crucial geopolitical zone, a nerve center of the migration conflict.

Today there are 56 border ports along the border, of which 20 are land crossings and 36 are bridges that facilitate the transit of people and goods. Legal access points are vital to trade, tourism and the daily lives of the roughly 12 million people who live in sixty cities on both sides of the border, which runs through six Mexican states and four U.S. states.

The entire area is characterized by movement from north to south and vice versa, when people work or study on one side and live on the other. But some cross only to the north and not through the checkpoints, but rather as far away from them as possible: the thousands of migrants who try this every year in search of a better life.

Fleeing their countries of origin due to violence, poverty, the ravages of nature caused by climate change, political crises, or lack of opportunities, migrants from Latin America, the Caribbean, and even Africans, Asians and people from the Middle East undertake a journey full of dangers, guided mostly by human trafficking groups who sell them the expensive promise of taking them to their dream destination.

The journey can last weeks or months and involves walking long distances and crossing several countries in South and Central America aboard the most diverse and precarious means of transportation.

There are no guarantees. Anything can happen along the way. Some threats are natural, such as crossing the intricate Darién jungle in Panama, full of geographical features, intense humidity, and wild animals; others are social, such as extortion, threats, kidnapping and rape, by gangs or paramilitaries as well as by local authorities.

When finally reaching the southern border of the United States — those who make it — the ordeal will not be over yet. More extreme weather and complex, diverse and hostile geography lie ahead. From a river with apparently calm waters that can be turbulent, to rugged places where summer temperatures are around 40°C and in winter they can drop below 0°C.

However, the last great obstacle to overcome is the Border Patrol, attached to the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and in charge, as its name indicates, of patrolling the United States territory along the border. So far in 2024, more than a million people from more than 80 countries have been apprehended.

The Border Patrol divides the border into nine sectors, each with multiple stations, totaling 71. From west to east, the San Diego sector covers 97 kilometers of land border and 183 kilometers of coastline, with 8 stations, and of course, includes San Diego, the sixth most populous city in the United States. The El Centro sector covers 113 kilometers of land border with 4 stations. Yuma covers 203 kilometers, with 3 stations monitoring dunes and military reservations.

The Tucson sector spans 418 kilometers with 8 stations, covering Tucson itself, Phoenix and Nogales. El Paso covers 431 kilometers, of which 142 follow the Rio Grande. The sector has 11 stations in New Mexico and Texas. Big Bend, with 821 kilometers of land border, is the largest sector and has 10 stations.

The Del Rio sector covers 338 kilometers and 9 stations, being the most agricultural area with numerous farms and ranches. Laredo, with 275 kilometers and 9 stations, includes the city of Dallas and several rivers that flow into the Rio Grande. Finally, the Rio Grande Valley sector, the most traveled by Central Americans, covers 508 kilometers between the river border and the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, with 9 stations in cities such as Brownsville, Rio Grande City, Corpus Christi and Kingsville.

The “wall”

The most media-covered aspect of the border is usually its physical barrier, the so-called “wall” that Donald Trump promised to contain illegal migratory flows. In reality, it has always been a heterogeneous structure that today covers a third of the border (about 1,130 kilometers), along very different ecosystems that therefore require different security approaches.

The different prototypes are part of a long history in which both parties have tried to sell to the U.S. public and the world that they can forcibly stop border crossings simply by “closing the border,” as if this were possible.

In some areas, the fence is composed of solid concrete blocks and iron bars. In others, the prototype is reinforced with double or triple fences, which increases the complexity of the crossing. However, in some remote or difficult-to-access areas, the barrier is replaced by long stretches of barbed wire, iron crisscrossing structures, and concertina wire mesh, which act as less forceful but effective deterrents.

The first border fences to contain immigration from the south began to be installed during the administrations of Democrats Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, after decades of building fences to stop the passage of animals. The trigger was a significant migratory flow that was unleashed in the 1940s and 1950s.

But it was not until 1965, under Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, that a limit was imposed on the number of people who could immigrate to the United States from countries in the Western Hemisphere such as Mexico. The change in regulation directed greater attention to the border.

In the following decades, the physical barrier grew or was modified under different administrations, both Democrat and Republican. Up until the 1990s, when xenophobia and public debate on illegal immigration increased in the United States, prompting both parties to move towards physical border security.

In 1993 and 1994, Clinton launched three separate border operations: Operation Hold the Line in Texas, Operation Safeguard in Arizona, and Operation Gatekeeper in Southern California.

Clinton established a “get tough policy at our borders,” expressed in the anti-illegal immigration program Operation Gatekeeper. He used surplus military landing mats for the fences to build a supposedly impassable wall. While these barriers were being erected, NAFTA opened the border to material goods.

Since then, each successor, up to President Biden, built a part of the wall.

In 2016, Donald Trump had as one of the main points of his campaign the promise to build “a wall” along the southern border of the United States. In his speeches he repeated that he would build the wall and would make Mexico pay for it. However, it was a promise impossible to keep for economic, technological, topographical and even biological reasons.

Before Trump was elected president in 2017, there were already several types of fences covering a total of just over 1,000 kilometers, in the states of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. Although at the end of his term he boasted of having built 800 km of wall, in reality, what he did was repair and reinforce a large part of the existing structures that were in poor condition. Less than 100 km were built during his term.

The most recent prototype consists of a giant iron fence, with between 5-and-9-meter-high masts on a concrete base.

Not only is it an imposing iron and concrete fence, but it is also equipped with an advanced security system in critical areas. It includes up to three containment barriers, high-intensity lighting, motion detectors, electronic sensors, and night vision equipment, all connected to the Border Patrol. Surveillance is constant, with all-terrain vehicles and helicopters patrolling day and night.

From a distance, the fence that marks the border in the desert near El Paso, Texas, stands like a giant scar on the arid landscape. Up close, it reveals a scene of desolation and flight: fragments of cloth from what was once a shirt, a torn shoe, broken and scattered toys…traces of those who passed through here and the conditions in which they did so.

In the territory near the border, tragedies occur daily. Reports of falls by migrants trying to climb are common. Some are seriously injured; others die. They often get caught between the wires from above, which increases the risk of fatal accidents.

For those who live in border cities and towns, this strange wall has been part of the landscape for three decades, and its presence has marked them as individuals and as a community, on both sides of the border.

Natural obstacles

The complex topography and its fauna, together with many other factors, such as high construction costs or the presence of private property in certain sectors, make it practically impossible to erect these structures in the remaining 2,000 kilometers of the border. Instead, barbed wire barricades known as concertinas are used. The rest of the border barriers are natural: mountains, rivers…

A part of the fence ends at the foot of Monte Cristo Rey — a natural border that divides the U.S. state of New Mexico from Chihuahua, in Mexican lands. Every year thousands of pilgrims climb its slopes, recreating the Via Crucis. The mountain, with almost 40 square kilometers and 1,400 meters above sea level, is also used as a route by human trafficking gangs. But passing through Monte Cristo Rey is an extremely difficult and painful feat, not in vain it evokes the path that Jesus took to the cross.

“Since there is no wall on this mountain, criminal organizations, drug cartels, coyotes and human traffickers think it is an advantage and use this route to penetrate into the United States. However, the area is very difficult to travel due to the elevations, blind spots, rocky and uneven terrain. We have rescued people with serious injuries after serious falls, or dehydration. Migrants are merchandise for criminal organizations. That is how they treat them, they are disposable,” explains Orlando Marrero-Rubio, an agent and emergency medical technician for the Border Patrol in El Paso, in a meeting with journalists at the foot of Monte Cristo Rey.

The desert is very close, another dangerous odyssey. The dry, burning heat and the threat of a variety of wildlife with coyotes (the original ones), jaguars and poisonous snakes, add to the danger of the crossing.

With temperatures that in July and August can exceed 40 degrees, migrants, after several days of walking, poor nutrition and worse hydration, are often disoriented, dehydrated and abandoned by traffickers.

“It is an area where we find people almost on the verge of death,” added Marrero-Rubio, and explained that in the current fiscal year — October 1, 2023- September 30, 2024 — 757 migrant rescues have been carried out in this area alone, where they have also found 132 corpses.

The same agent showed one of the rescue towers installed in remote and rural areas. “These towers are equipped with a big red button that, when pressed, activates the emergency system and gives us the coordinates to arrive and offer assistance,” he explained.

About a thousand kilometers from that point is the Rio Grande Valley, a vast region that spans southern Texas along the border with Mexico. This has historically been one of the most critical points in the migration crisis. Although the landscape is different from that of the desert, the danger for migrants persists.

The main border in this region is the famous Rio Grande, the fourth longest in North America. On the other side, in Mexico, it is called the Rio Bravo and is the longest tributary in the nation, from the San Juan Mountains in Colorado for 3,034 kilometers until it flows into the Gulf of Mexico. Of these, approximately 2,000 kilometers form the natural border between the United States and Mexico, from the cities of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, to the Gulf.

It is a body of water whose width and depth vary significantly along its route. It is relatively shallow and wide. Where migrants usually cross is between 1 and 2.5 meters deep and between 5 and 50 meters wide. Its waters, although they seem calm, “are treacherous,” says Border Patrol agent Andrés García, spokesman for the Border Patrol, in the middle of the jungle, a few meters from the banks of the river.

“The border is extremely dangerous. Although we have seen a slight decrease in numbers, there are still between 200 and 300 daily entries in this sector, which is still considerable. We understand that migrants make this journey out of necessity, but it is crucial to warn about the risks. The river is treacherous because it has deep currents that take you to the bottom. It has claimed countless lives. In addition, there are rattlesnakes, crocodiles and a tick that bites and causes very high fevers. These risks, added to exhaustion and extreme heat conditions, can make a migrant’s journey the last one they make.”

Mabel*, a Central American woman in her 30s, knows this very well. After being kidnapped on her way through Mexico and suffering other humiliations, she almost drowned while crossing the Bravo with her 2-year-old son.

“I never imagined that that river that seemed calm was so dangerous. The water came a little above my waist. I could walk and the other shore was close. I was carrying my son on my head. Suddenly, a current began to drag me along. The river was very strong. It was stronger than me. I was very scared. A man was coming behind me and I screamed desperately for him to help me with my son. I already thought I was not going to be saved. He took my baby and helped me get up to continue walking. When we got out of the river, the immigration patrol was very close, so I turned myself in. They took care of us, gave us food and clothes.”

Mabel remembers it and trembles. She cries while hugging the child tightly in a shelter in El Paso. There, with an electronic ankle bracelet that keeps track of her, she awaits a hearing with an immigration judge who will decide whether to approve her asylum in the United States or rule her deportation.

There are areas where it is not enough to cross the river. Other obstacles coexist: jungle terrain, wire fences and the imposing fence. For example, close to the banks of the river, a few kilometers from the international bridge that connects the cities of McAllen and Hidalgo, in Texas, with Reynosa, Tamaulipas, wildflowers are trapped between a tangle of sharp wire fences.

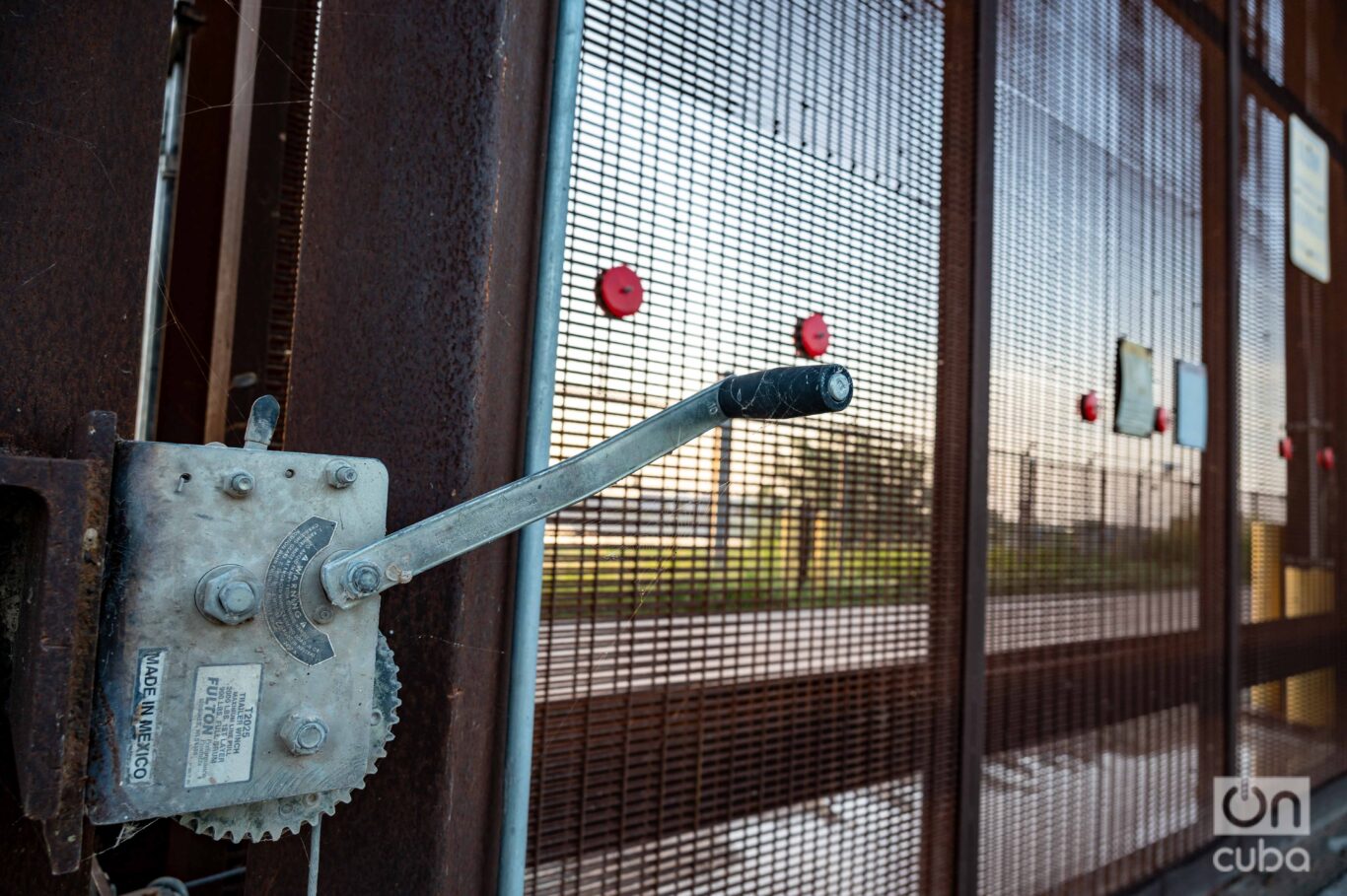

Right there, the sun rises, over U.S. territory. It could be a wonderful spectacle, but from the Mexican side, every day they receive a trapped sun: it can only be seen through the bars of one of the large doors of the imposing fence. Paradoxically, the crank that activates the opening and closing system has a sign saying “Made in Mexico.”

*For privacy reasons, the real name of the witness has been changed.

To be continued…