In an analysis of the current situation in Cuba, economist Julio Carranza warns that the island faces at least three crises. “A macroeconomic one, a growth one, and one of the economic model,” he said.

The doctor in Economic Sciences and former regional advisor to UNESCO explained, in an interview with OnCuba, that the nation also faces problems associated with infrastructure, the demographic situation, and electricity generation, among others.

He also considered that the international panorama is not entirely favorable. “We do not have large international alliances, as in the past. There are many friendly countries, good relations with many states, but alliances that imply, for example, a significant preferential economic treatment, beyond how important the relationship with Venezuela has been, do not exist at this time.”

The conditions that have accompanied the economic reality of the island in the last 60 years also remain. “Cuba is a small country, with very limited natural resources, located in a very complicated geopolitical area, close to the United States, a great power with a very hostile policy,” he said.

“When there is a situation as complicated as the one Cuba has, which is due to historical factors of a diverse nature and is expressed in an economic and social crisis, the way to overcome it strategically is by making a fundamental transformation of the model of operation of the economy and society,” Carranza reflected.

In his opinion, the horizon of this reform must be socialist. However, he warned that it is necessary to define what socialism means in Cuban conditions. “The rigid schemes of historical socialism are not adequate to respond to this problem,” he said.

The heart of the reform

Julio Carranza insists that the debate between the different social actors is key to transforming the economic reality.

“Economics is a social science and it is because it does not study relationships between things, but between people. Therefore, this discussion about the economy has to be more open, participatory, better understood by people, especially in a time of crisis and necessary changes,” he said.

The expert believes the so-called socialist state enterprise and agricultural production should be “the heart of the comprehensive reform.”

“We have a system of enterprises that, with a few exceptions, is essentially inefficient and that is where most of the economy is. Enterprises have to be the object of a transformation, not so that they stop being state-owned, but so that they stop being inefficient. To do that, they have to be integrated more autonomously with the market,” he said.

He affirmed that it is necessary to generate competitiveness and move from a bureaucratic and administrative planning of resource allocation to a more financial and indicative one. “To remain tied to the planning methods of the old socialist European countries would be a foolishness that could be very costly,” he said.

Meanwhile, Carranza explained his opposition to the term used to refer to state-owned enterprises on the island. “I prefer to call them public. In a country like Cuba, when it is said that this is the socialist state enterprise, it means that the others are capitalist, which places the private sector in an anti-system logic that generates prejudices,” he said.

“What is socialist or capitalist is the system that integrates them, how markets are regulated, in which social wealth is redistributed, how there is popular participation and people’s power is maintained through democratic institutions,” he said.

On the other hand, the economist, referring to agriculture, commented that this sector has many limitations, which have been tried to be solved with a list of measures. “But, what is needed is a transformation of the concept of how food is produced in Cuba,” he asserted.

In his opinion, this change would include a discussion on the role of the private sector in agriculture.

“The majority of food is being produced by the private sector; however, it is full of limitations. From the collection structures, which by definition are not bad, but do not work well, to the access they have to production conditions, including land,” he said.

Carranza also criticized the imbalance in Cuba’s investments and their impact on the sector.

“The investment policy, by all accounts, does not seem to respond to the country’s fundamental priorities because there is more than 30% concentration of investment in the real estate-hotel sector and less than 3% in agriculture. It is also insufficient in other fundamental sectors such as health and education,” he commented.

This means, according to the economist, that the scarce national resources are being invested in tourism, when this sector is not now in a position to repay that investment. Meanwhile, agricultural production needs capital.

* A Flourish chart

Cuba is not growing

“One of the most critical problems in the Cuban economy is that it has lost its capacity for growth, that is, its potential to generate production and increase the supply of products and services,” Carranza said.

In fact, the island’s economy contracted by 1.9% in 2023. The economist identified some of its causes. Among these, the sanctions of the United States government.

“Without a doubt, the blockade (embargo) is criminal; however, modifying it is not in the hands of the Cuban government. Therefore, this problem must be overcome despite the blockade,” he said.

Another cause is the “blow” that the sugar industry received, which was “the backbone of the Cuban economy for centuries.”

“Cuba went from producing more than 8 million tons of sugar in 1970 to less than a tenth of that figure today. The reduction has been significant; therefore, the fundamental factor of articulation of the Cuban economy in internal terms and its connection with the outside world received a very strong blow without having a substitute,” he explained.

He also commented on another of the difficulties that the island faces in promoting economic growth: the foreign debt.

“Cuba has a debt that constantly forces it to seek ways of renegotiating and subjects it to international claims, both bilateral and multilateral. This closes off access to credit. We must find ways to solve the problem. I agree with some economists who have proposed paying a part with national assets, under novel formulas and financial engineering,” he said.

In addition to this reality, the nation has a long-standing problem: the inconvertibility of the Cuban peso.

“It was expected that with the Monetary Reorganization, a single currency and exchange rate would be established; however, today we have more currencies and more exchange rates than ever before,” said Carranza, who described this program, which began in 2021, as the most delicate mistake that has been made in recent years.

“The Monetary Reorganization, without having created preconditions for the growth of the supply of products and services, abruptly multiplied by 24 a significant part of the costs of state-owned enterprises, with which the increase in prices was immediate. An attempt was made to solve this with the increase in salaries and pensions, but, in the absence of a productive response, what occurred was a greater inflationary process, present until today,” he explained.

Getting out of the zone of turbulence

Before undertaking comprehensive changes in the Cuban economy, Carranza points out that some issues that define the success of the process must be resolved.

“When an economy is under macroeconomic imbalances, it is like when an airplane is passing through a zone of turbulence. The first thing is to get out of there in order to then be able to get back on track. The entire process of change is conditioned by the restoration of these balances, which give economic actors and consumers a space for functioning in a more normal and stable way, and not with the great tensions of today, which are expressed not only in difficulties in the food sector but also in healthcare, fundamental services, such as electricity, water, infrastructure, banking, and others,” he explained.

Antonio Romero: “In Cuba, dogmas prevail over economic rationality”

One of the expressions of these macroeconomic imbalances is inflation, which, the expert warns, has the potential to generate social tensions.

“Inflation means a process of depriving people of their resources, especially the most vulnerable groups, who in Cuba are the vast majority today,” said Carranza, who criticized the price cap measure approved by the government last July, since what actually happens is that products end up on the black market.

The economist expressed his concern that there is no public plan on how the government plans to restore macroeconomic balance.

“I heard talk of a plan until 2030. We are in 2024 and six years is a long time. Politically it cannot hold up. There must be more immediate solutions,” he pointed out.

In this sense, for Carranza, the most critical and worrying economic, social and political problem that Cuba currently has is that the most basic needs cannot be covered with salaries and pensions. “It is a problem that touches human dignity,” he emphasized.

He gave the example that the average salary is around 4,000 Cuban pesos and a carton of eggs costs 3,000. “It is a serious problem.”

“In a society of workers, like ours, what should be most valuable and recognized is people’s work. Salary is material compensation, recognition of the condition of being a worker. When the salary is not functional, what they are telling you is that your work, your condition as a worker, is useless,” he said.

Julio Carranza said that a “new, open, anti-dogmatic mentality, without paradigmatic paralysis” is required to address and resolve the island’s economic problems. “Time goes by, contradictions accumulate and can lead to very complicated social and political situations,” he said.

Time has been lost

“If the transformation of the economy had begun more deeply in the second half of the 1990s, we would have made much progress,” Carranza said.

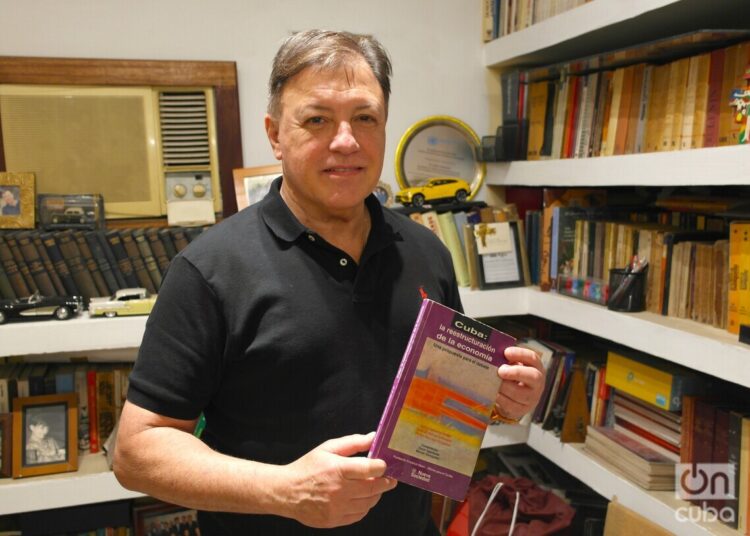

It was not for lack of proposals, because together with him, two other economists (Luis Gutiérrez and Pedro Monreal), wrote the book “Cuba: La reestructuración de la economía: Una propuesta para el debate” (Cuba: The Restructuring of the Economy: A Proposal for Debate), published by the Ciencias Sociales publishing house in 1995 and by other foreign publishing houses later.

“It was widely disseminated, but not a significant impact on the policies that were being made in the second half of the 1990s,” lamented Carranza, who, together with his colleagues, proposed ideas that the government finally approved almost 30 years later, such as opening up to the private sector.

The text focuses its thesis on what a comprehensive reform means and the steps to achieve it, after the fall of the socialist camp and the extinction of the benefits that sustained the Cuban economy until then. Changing the “exhausted” economic model.

He also reflects on the role of the market in a socialist nation.

“There is a strong idea within this proposal, which is that socialism is also a mercantile society. The difference with capitalism is that in the latter all relations are basically explained and dominated by the market, especially in its neoliberal version. And in socialism, this market must have economic regulation and there must be some activities that are outside the market, because they are essential for human beings, such as healthcare and education,” the author commented.

In response to the judgments that oppose the expansion of the market in Cuba, the economist called for understanding this system as what it really is. “It is a social relationship of objective production, which exists beyond the will of people, which has to do with the only way in which an economy with a scarcity of resources can function. And all economies have them,” he argued.

On the other hand, he insisted on the need to regulate the market, but not with “capricious or administrative” measures, but with “economic methods” such as “fiscal policy, monetary and exchange policy, investment policy, social policy, attention to workers’ rights.”

He also specified that in Cuba the private and cooperative sector must have “markets that function, with infrastructure, credits, a functioning bank, wholesale markets, the ability to make decisions and, of course, also rigorous controls, such as an adequate fiscal policy that reduces evasion and that taxes are objectively related to the activity of the enterprise.”

Oscar Fernández: “En Cuba deberían enfocarse más en el progreso y no en el control”

Carranza insisted that, although some elements would have to be adjusted, the conceptual proposal of his co-authored book remains valid. He even stated that there is now a much more favorable scenario to have this discussion, after the approval of the Conceptualization of the Economic and Social Model and the Constitution, in 2016 and 2019, respectively.

However, he assured that the island is very far from the potential for economic transformation that, from a political point of view, these documents allowed.

When questioned about the causes of this reality, Carranza explained some of them.

“The first factors are ideological, from old ways of thinking, which identify the market with capitalism. And, therefore, some fear that a greater presence of this will lead to a process of regression of the Revolution. Second, because, like any new issue, it generates fears. It is always a challenge to leave the comfort zone. This economy has been run in a certain way for several decades and there is a certain inertia, a tendency to remain under that administrative form. And third, because there are vested interests, many of them spurious,” he acknowledged.

According to the economist, these resistances are strong. “Sometimes, the top leadership of the government says things and then they are not done,” he added.

He considered that, frequently, an old-fashioned discourse is maintained that asks for the economy to grow, but the policies that are implemented do not correspond to that request.

“Of course, there will always be contradictions. They must be dealt with and resolved politically, and with an economy that works, with economic foundations. That is a great challenge. But time is not infinite. We cannot live forever dragging the problems we have, or the difficulties of people today in their daily lives,” he concluded.

Cuba is a BRICS partner. Is that helping it?