Many years later, in front of the cameras, Jacqueline Arenal Farré was to remember that distant afternoon when Pablo Milanés introduced her to his friend Gabriel García Márquez. After decades, the actress has been chosen to be part of the cast of the film adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude, one of the most ambitious productions in the history of Latin America.

Jacqueline, with whom I speak by phone regarding her participation in this Netflix production, cannot and does not want to hide the emotion she feels at having given life to one of the characters that populate the mythical Macondo. It is not just another role in her successful career. It is a connection with the literary universe of the Colombian Nobel Prize winner and a personal tribute to the legacy of García Márquez.

The tone of her voice betrays euphoria. Although I cannot see her, I can imagine the expression on her face: a mixture of pride and enthusiasm that, without a doubt, lights up her gaze. A look that has conquered both the Cuban public and international audiences, whether from the theater, television, or the big screen.

Jaqueline Arenal gives life to Leonor, the wife of Don Apolinar Moscote, who arrives in Macondo as the mayor of the conservative government, although his authority is more symbolic than effective. In the novel, her character does not have a name and is described as “a well-preserved woman, with grief-stricken eyes and gestures.”

However, in the adaptation for the series, she is called Leonor, as part of the creative licenses that characterize this production.

The Moscote couple has seven daughters; among them is Remedios, a sweet and charming girl who, at 9 years old, awakens the love of Aureliano Buendía, who asks for her hand in matrimony. The wedding is postponed until she reaches puberty when she becomes a beloved figure within the Buendía family. However, her tragic death, pregnant with twins and not having turned 15, plunges the house into rigorous mourning, symbolized by a daguerreotype of her that Aureliano’s cousin Úrsula always keeps illuminated.

Leonor Moscote is a complex character who embodies both vulnerability and strength amid an oppressive environment. Although she may initially seem like a conventional aristocratic wife, her story reveals the tensions between the social, family, and personal expectations that surround her. Despite the impositions she faces, Leonor shows flashes of resilience and humanity and leaves a significant mark on both the Buendía family and the Macondo universe.

The first part of the series will be available on Netflix on December 11. But before its global launch in Colombia, the streaming platform will screen the first two chapters in a few screenings at the Havana Film Festival. The series has had similar screenings in major cities such as Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Madrid, Barcelona, Paris, London, Brussels, Warsaw, and Los Angeles, reflecting the global impact of the adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Amid these events, the conversation with Jacqueline arises. She speaks from her home in Havana, while I listen attentively from Buenos Aires. Her answers to my questions transform distance into an illusion, as if we shared the same space, in the best style of the magic realism that brings us together.

Your life seems to be woven by invisible threads, where literature and cinema intertwine. Your first big leading role came when you were still studying acting at the ISA, in the film adaptation of Explosion in a Cathedral (1993), under the direction of Humberto Solás. Then you gave life to Sofía. Thirty years later, with a consolidated career, you come to this ambitious series…, an adaptation of a classic of Spanish literature and curiously also with an evocation of a hundred years.

For One Hundred Years of Solitude, an intense and multitudinous casting was done. At first, my only concentration was on preparing to get a place in the series. Then, when I was selected and began to study the script and record, I felt that it was like closing a perfect cycle in my life. I began my career with a Caribbean period piece, Explosion in a Cathedral, and now I close it with One Hundred Years of Solitude, which is an essential and deeply close reference for me, not only for me but for so many people in Latin America and the world.

Beyond your relationship with Colombia — where you are not a foreigner —, as a Cuban there is a particular connection with magic realism, which in Cuba is part of our identity in a very particular way. That Cuba-Macondo marks us deeply from the moment we are born.

(Laughs) You’re right: we have grown up in our own Macondo. It is a very living reference. For younger Colombians, who are faced with telling this story, it may be necessary to go back in time. But for us Cubans, that magic reality is something that is still present.

I remember talking with other actors, especially with the very young actresses who played my daughters, explaining to them how to understand the depth of what happens in the novel, because what happens there has a direct connection with our daily history.

Do you remember your first approach to One Hundred Years of Solitude?

Of course! And I have a very nice anecdote. Before studying acting, I trained in classical ballet. In the last few years, at the Ballet School, we met with several Latin American students. I was 16 or 17 years old. One of them, Colombian, was my boyfriend at the time. He gave me One Hundred Years of Solitude. It was the first time I read it, and I was fascinated. I still have that copy, a beautiful edition with a leather cover.

How did you meet Gabo in person?

I had the pleasure of meeting and talking at length with him, at Pablo Milanés’s house. He was always very cordial and kind. One night, we even danced salsa at the Tropicana cabaret. When I met him, I ran to tell my father [the writer Humberto Arenal]. It was a huge emotion. That possibility of being close to the man and seeing his greatness was really moving.

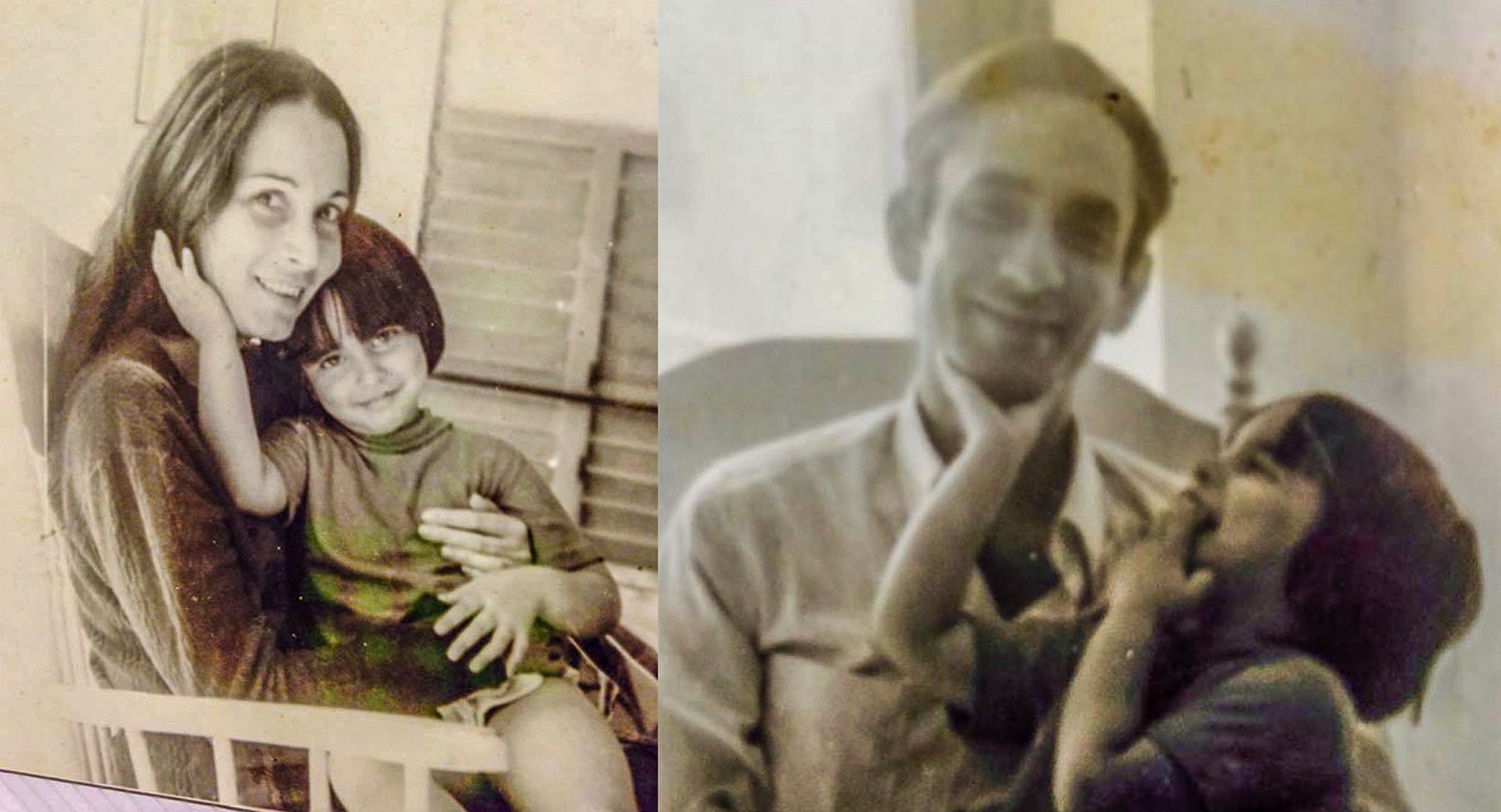

It is impossible to ignore your roots. On the one hand, your mother, the actress Marta Farré, who left a mark on the stage, and on the other, your father, the writer and playwright Humberto Arenal, winner of the National Prize for Literature. With that legacy, it seems almost natural that your artistic path was forged between literature, stages, and cameras. Could it be said that, between the Jacqueline of the Explosion in a Cathedral and that of One Hundred Years of Solitude, there is also a bit of the legacy of your family roots?

It is very much so! The fact that I was able to approach that world intellectually and emotionally, so early in my life, has a lot to do, for example, with the reading habit that my parents instilled in me. Television was slow to arrive in my house. While it was already common in Cuba for many families to have a television, even in black and white, in mine there was none. I grew up in a home full of books; my world was books. Even when I was very young, I felt that my parents insisted too much on me reading. Over time, I thanked them for it, because today, as then, practically nothing fulfills me more than immersing myself in the reading of a good book. That is still a marvel, a magical moment.

And it is curious because I remember that to play my role of Sofia in Explosion in a Cathedral, I relied deeply on the universe I had imagined when reading García Márquez’s novel years before. Incredibly, I felt that this literary world served as a close reference for me.

It makes sense. Carpentier introduces the concept of “the marvelous reality,” which precedes García Márquez’s “magic realism” and becomes a key influence for the writers of the boom. How complex can the preparation of an actress be to play a character from literature, and more so from a famous book?

It is a very complex process, not only for the actors, but also for the directors, screenwriters, and everyone involved in adapting a novel to film. Each one has his or her own image of places, characters, and situations, shaped by their readings and their personal interpretation of the book.

In One Hundred Years…, excellent work was done. The written dialogues, for example, are very few. Cinematographically, this implies that the description of the era, the characters and the conflicts had to be much more detailed. There was also the challenge of how these characters would speak. These, although wonderfully described in the book, do not have a specific way of speaking, which leaves room for interpretation.

Did they ask you anything specific in terms of the work on the accent for your character?

The work on the accent was a fundamental aspect of the construction of the character. Most of the actors were from the coast or had a certain closeness to that Colombian accent, which facilitated the process. However, a joint effort was made so that we all achieved a coherent way of speaking, appropriate to the region, considering the diversity of accents that exist in the Caribbean. The objective was to approach an accent closer to the Samario, typical of Santa Marta.

To do this, we had the invaluable support of a team of accent coaches who accompanied us during rehearsals. While we were studying our characters, we could consult them constantly. In addition, they were present on the recording set to correct any detail in real-time.

It was not simply a matter of personally interpreting how a coastal person from Santa Marta or Cartagena might speak, but of ensuring that the entire cast maintained uniformity in the accent. Added to this was the challenge of reflecting, through pronunciation and intonation, the social differences between the characters, which also influence their way of speaking.

One of the most tense and controversial passages in One Hundred Years of Solitude has Leonor Moscote as its protagonist, when Aureliano Buendía, an adult, goes to the Moscote house to ask for the hand of Remedios, a girl of just 9 years old. How did you approach the interpretation of your character in such a controversial passage?

My character is a deeply traditional woman, consistent with the culture of her time. In that context, what she did was part of normal behavior, even seen as an act that ensured her daughter’s future. However, this perspective contradicts the vision we have today, a vision that I fully identify with as a mother.

It was essential to understand the motivations of the time and those of each character. Leonor is a woman who raises her daughters as best she can, an intelligent woman who is aware of everything her husband is up to, but who, despite that, does not have a powerful voice in front of him. She is deeply immersed in her role, masterfully representing what may seem minor: the woman who is dedicated to raising her daughters and, ultimately, providing them with the most important tools for life.

In this sense, her role takes on enormous importance. However, I myself experienced contradictions, especially when justifying her support for her daughter’s marriage when she is so young. Although Remedios makes the decision, Leonor supports her, since, in her time, it was a common practice. In addition, this act also brings a bit of peace and is influenced by the political events of the moment. [We must not forget that José Arcadio Buendía and Don Apolinar Moscote have an antagonistic relationship, marked by both political and personal differences.]

It has been said that the town of Macondo, built in real size for the series, is impressive, something rarely seen in this type of production. What were your impressions? What feelings did being there awaken in you?

I have never experienced something like this in my life. This is a dream come true, because generally, due to production problems or any other factor, an entire town is never built in real size, with its houses, the church, the natural plants… just to film.

They took us to see the town a week before starting to shoot. When we arrived and saw that, Marlyeda Soto — who plays Úrsula Iguarán as an adult — and I burst into tears. Despite our careers and all our experience, it was so exciting that we couldn’t believe it. It was an absolutely impressive moment.

I must emphasize that all of this was possible thanks to the professional rigor with which work was carried out. Each department, whether it was the technicians, the art department, the costume department, the photography department, or the direction department, did an impressive job. The directors [Argentinean Álex García López directed episodes 1, 2, 3, 7, and 8, and Colombian Laura Mora was in charge of episodes 4, 5, and 6], when they were directing, you realized that they had not only studied the novel but that they knew the story and the context in detail.

I confess that being in that setting, in Macondo, represented a fundamental part of our inspiration to work. Even when we saw on the monitor the scenes that we had finished recording, the emotion came not only from what was shown on the screen but from what surrounded us. I have enormous faith in the series.

***

The “García Márquez angel” seems to have always been present in Jacqueline Arenal’s life. With the arrival of the series to Havana, its natural audience, the actress feels honored. The presentation of the first two chapters at the Film Festival has a special meaning. Gabriel García Márquez always maintained a close relationship with Latin American cinema and a deep friendship with Cuba and its people.

“I would have very much liked for my parents to be alive and to be able to enter the movie theater hand in hand with them to see the premiere of One Hundred Years…in Havana,” Jacqueline confesses almost as she says goodbye. While she says it, I cannot help but, as at the beginning of our conversation, imagine another act of magic realism: Pablo Milanés and Gabriel García Márquez appearing together from some corner, entering the movie theater to take a seat among the audience, smiling, applauding when they see Jacqueline, a Cuban, in the heart of Macondo. In the end, the unreal seems as possible as the everyday, especially when the Macondo universe comes to life on the screen and in the souls of those who inhabit it and carry it with them.