Two years ago, just after the 27th Alicia Alonso Havana International Ballet Festival and with the Josefina Méndez International Honorary Dance Award in his hands, I asked Joaquín de Luz (Madrid, 1976) if the Cuban audience would see him again. His answer was emphatic: “Sure. I don’t know how yet, but I’m sure I will. I’m in contact with Viengsay Valdés to do some collaboration.”

I remembered that promise as the curtains closed on the 28th Festival on November 10, after the choreographic gift that the Spanish dancer gave us. The world premiere of Gitanerías was the icing on the cake of the event. With the music of Ernesto Lecuona as the guiding thread, it brought together on stage De Luz with Viengsay Valdés and the pianists Marcos Madrigal and Aldo López-Gavilán. The Cuban audience witnessed, once again, the genius and sensitivity of its author, one of this century’s most prestigious international dance figures.

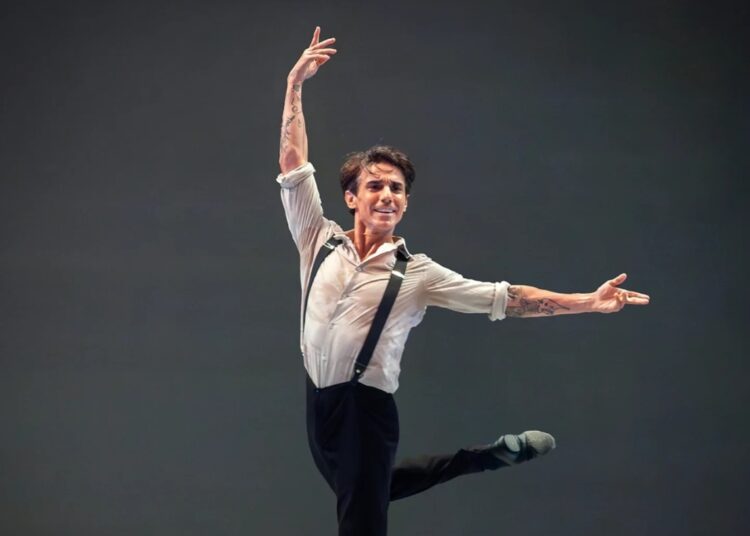

At 48 years of age and having just finished his period as artistic director of the National Dance Company (CND) of Spain, Joaquín returned to the event in Havana with the same enthusiasm with which, on previous occasions, he has performed for the Cuban audience. He knows the way back, with his eyes closed.

Joaquín’s bond with the Cuban audience has a pleasant aftertaste. In memory remain his Cinco variaciones sobre un tema — a solo created by David Fernández for De Luz himself — or the pas de deux from Giselle, which he danced with the Russian María Kochetkova in 2018 and which was the prelude to that powerful tandem to take on the complete ballet in the choreographic version by Alicia Alonso, in 2022.

From that year, the previous Festival, his interpretation of Albrecht still moves. But he also gave us Eterno, together with the dancer Sara Calero, a fandango for two hands — or four feet — dedicated to the genius of Picasso.

To the delight of the audience that had just emerged from a pandemic, Joaquín de Luz arrived with his entire troop from the National Dance Company (CND) and allowed us to see his facet as a leader, both on and off the stage — with the documentary Hasta el Alba, by Horacio Alcalá, we saw part of the creative processes of the group under the artistic direction of De Luz. The CND with its version, signed by the Swede Johan Inger, of the classic Carmen, “topped off” that celebration. A true revelation for Cubans.

With all these experiences still fresh in memory, the enthusiasm for the presence in Cuba of Joaquín de Luz, among other international figures, was undisguisable. In addition, this time a special confluence occurred within the walls of the headquarters of the National Ballet of Cuba, the host company of the Festival: Julio Bocca, Marcelo Gomes, José Manuel Carreño and De Luz, who once formed part of a particularly luminous moment of male dance at the American Ballet Theatre (ABT), met again.

At the ABT, De Luz shone notably. He would later become a leading figure of the New York City Ballet — between both companies, a toil of two decades —, stages where the legend that is today this performer was forged, winner of the Benois de la Danse Prize (2009) as best male dancer and the National Dance Prize of Spain (2016).

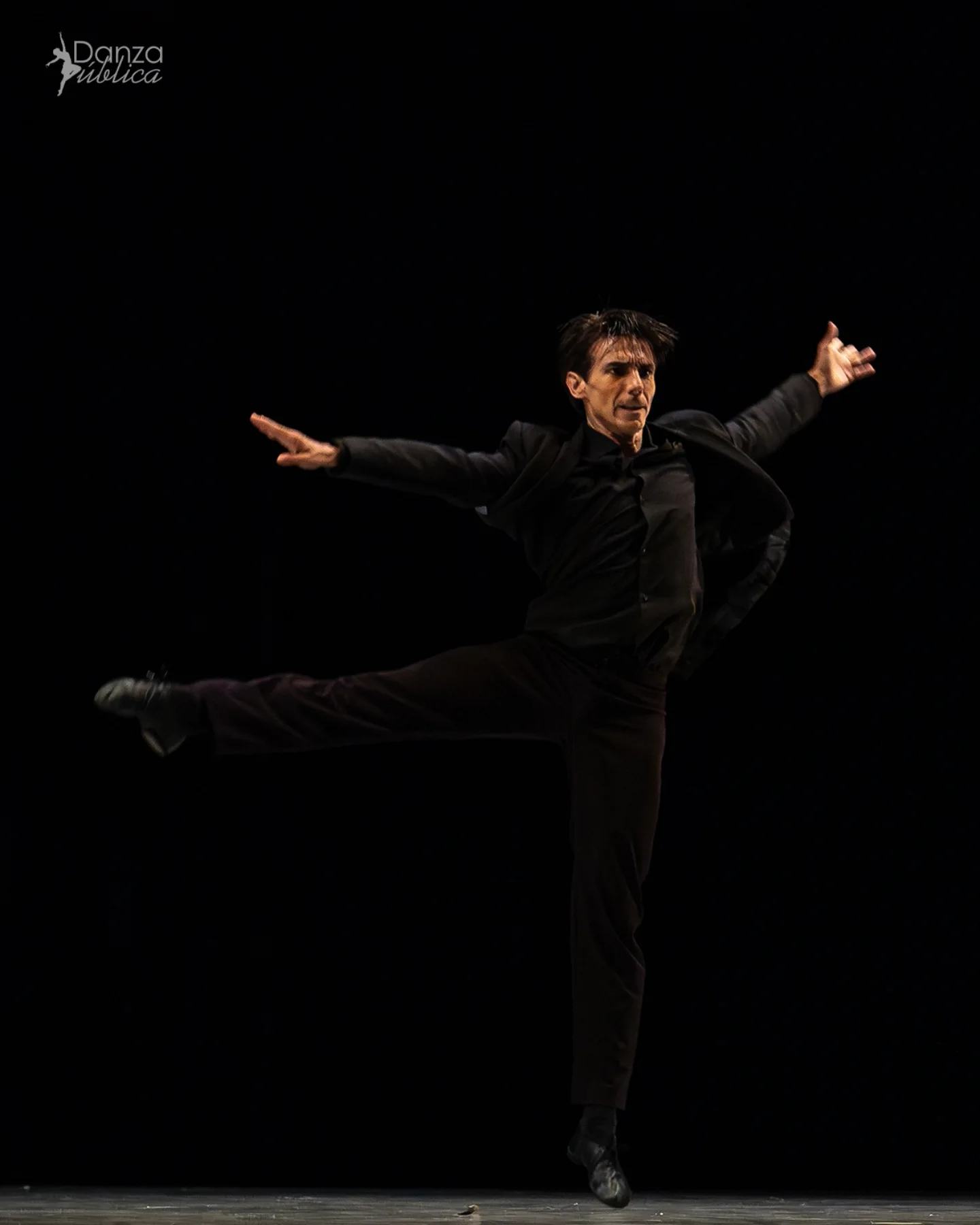

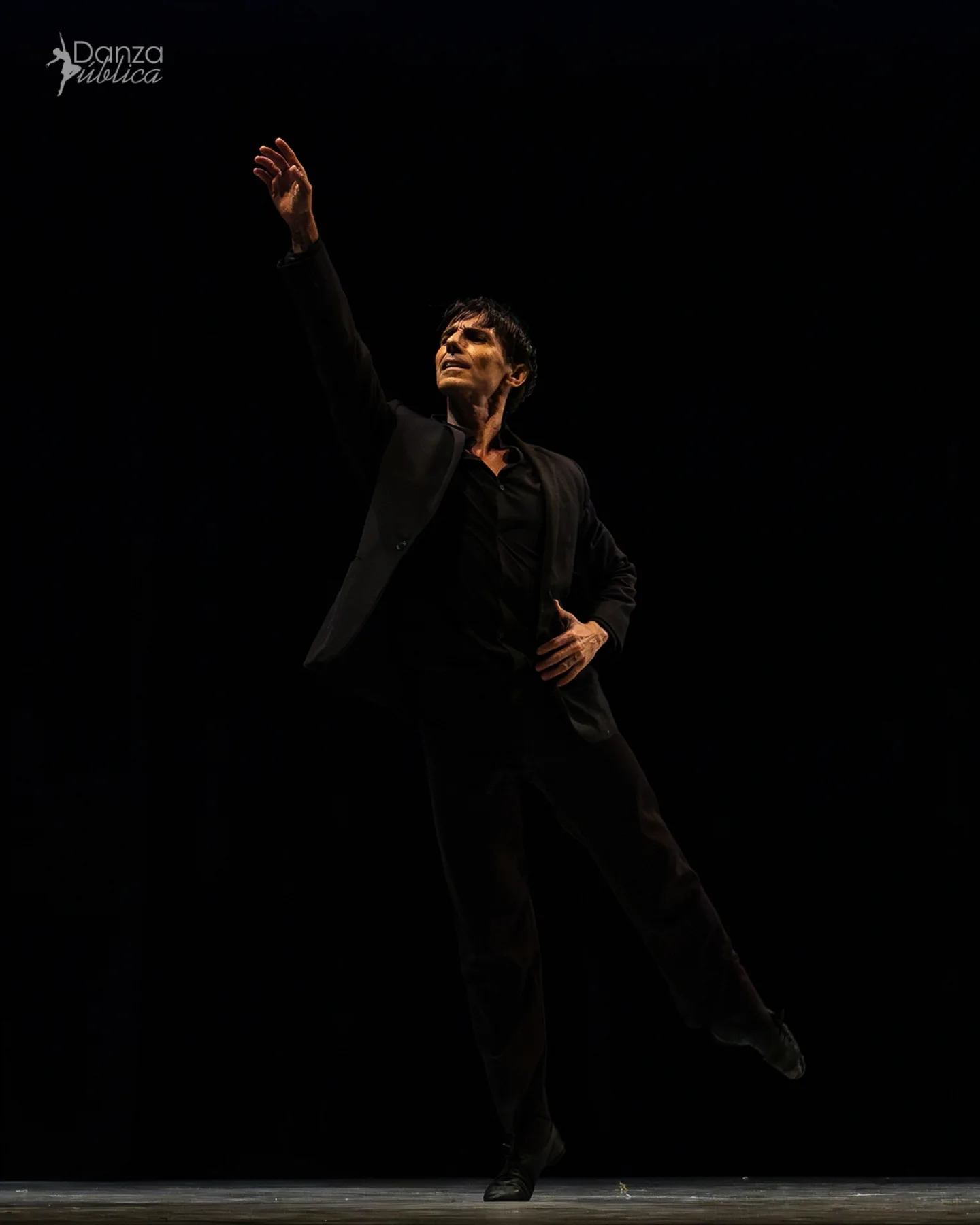

His mastery was once again evident when he appeared at this festival to dance his Farruca — named after the flamenco style originating in northern Spain —, a solo that forms part of the work A tu vera, composed by the Spaniard and Sara Calero.

He would then return to the scene in an exquisite duet with a salty flavor, a mixture of wind and sea, together with the Spanish dancer Patricia Donn, making her debut on the Havana scene. De quererte tanto was not only a piece capable of connecting with the audience, but also a declaration of intentions by its performers.

The day after that presentation, I met Joaquín de Luz when he arrived at the rehearsals in the Avellaneda Hhall of the National Theater of Cuba, where the closing gala of the 28th Festival would take place, as well as the expected closing with the world premiere of Gitanerías. Despite the rush, the setbacks imposed by Hurricane Rafael in those days through the western part of the country and the expectation that the moments before a premiere represent for an artist, there was time to talk about this new visit, dance and the future.

You are coming to the end of another Festival in Havana. How would you describe this visit?

With much affection and gratitude. This time I have had the opportunity to bring Patricia Donn (Spain) and Denys Cherevychko (Ukraine). When you bring people who have never experienced the Festival and what it feels like here, how it flows, it is very nice, because it is like hosting one of my favorite events, personally and professionally. So, opening the way for artists that I appreciate and seeing the same result, that they have a performance similar to my first time here, makes me very happy.

De quererte tanto raised many feelings in the audience. What circumstances surrounded the creation of that piece?

The idea was exactly the trip, the encounter between Spain and Cuba. It arose spontaneously; Patricia showed me the song of the same name, a guajira but sung by a Spanish flamenco woman. A music with traits from both shores. The clave sounded and I knew from the first minute that it was going to connect with the audience. The way we presented it also helped: an encounter between two temperaments, with a little conversation, a little flirtation. I think it worked very well and the audience identified a lot.

There was a lot of naturalness and harmony between Patricia and you in that piece. How was the work with her?

Well, it flowed very quickly. Whenever I go to work in a studio with someone from another field — flamenco in this case — I have doubts about how things will flow, whether there will be any bottlenecks. With her, everything was natural. I think that the confidence we have, that connection I felt from the first minute in the studio, was reflected on stage.

When you connect with a person and the audience perceives it, a solid bridge is built that goes beyond the performers. Here in Cuba, people know a lot about dance and expect certain things. But in the end, the human part is what touches us the most, the “soul.”

The audience that knows you and has enjoyed you already knows, to a certain point, what to expect from you as a performer. But, what do you expect in those moments when you are about to go on stage? What are the feelings that come to you as an artist on stage?

When you feel loved in a place, it is comfortable. All these years dancing at home (Madrid) have also been comfortable. You can dance a lot on stages around the world, but some are closer to you humanly. Here in Cuba, I feel the warmth of the audience, I feel that I am loved and that affection is mutual. I think that my conversation with this country has always been very honest. I have had that connection with the National Ballet of Cuba since they went to Madrid, to the Albéniz Theater, every summer. I went night after night to see them. Since then, the bond has been growing and evolving: the trips to Cuba, the good relationship with Cuban artists such as José Manuel Carreño, Carlos Acosta, Lorna Feijóo, among many others. They are bonds of brotherhood; I feel very identified with them. A feeling is produced immediately. I am a person who likes to socialize, not to be so serious always and not to leave aside the sense of humor. So, when I go out on this stage, I feel loved; it let me spread my wings a bit.

And what about Gitanerías?

At first we were going to do the piece with just Ernesto Lecuona’s “Gitanerías,” but it wasn’t enough for me, because that piece only has two combinations. I had previously done two pieces by Lecuona with another dancer and I suggested to Viengsay that we include “La Malagueña,” which is also very well-known and begins in a slightly more intimate key. On top of that, since we had these two “monsters” that are Marcos Madrigal and Aldo López-Gavilán, we let them shine too, and so ideas began to emerge.

The inspirations have to do with the people who migrated in the last century and escaped from the war in Spain and came here. It has a lot of bohemian and melancholy. The couple that dances has lived a love in the past and they meet in this recital. While the pianist plays, they enjoy the music, so it is at that moment of the night that the conversation begins, when you think if they are going to misinterpret the signals, if one looks in a certain way or says something that makes the other person uncomfortable. There is a lot of history there. I think that in the end what is understood is that these two people celebrate the part that brought them together, the joy, the good.

We also support ourselves with projections of old images of those people who emigrated. Lecuona means a lot to that union, that symbiosis between the Spanish and the Latino.

I had a great time with Viengsay; it’s the first time we’ve danced together and it’s been very easy. I’ve made her a little bit Spanish and she’s made me a little bit Cuban too (he smiles). She’s a great professional and I wish we’d had more time to rehearse, because we got caught in the hurricane and only had three days to prepare. A total challenge, but everything flowed very quickly.

For the piece you used “Gitanerías,” “La Malagueña” and “La Comparsa.” What do you feel about Lecuona’s music?

A tremendous emotion. I’ve been wanting to do something with Lecuona for years. I would have liked to take Tarde en la siesta — created by Alberto Méndez, with music by the Cuban composer — to the company (CND). I identify a lot with Lecuona’s music, because I think I lived here in another life (he smiles) and he has the perfect harmony between the two worlds, that connection of peoples who understand each other culturally and who have blood as a link.

How was your reunion these days with Julio Bocca, José Manuel Carreño and Marcelo Gomes?

It has been very nice. When I arrived at ABT I had been seeing José Manuel for years, I admired him; Julio Bocca was also an idol for me. When I arrived at ABT — I was a kid, I was 19 years old — those people welcomed me like a little brother, it was wonderful. It was a time when they not only helped me in the studio, they stayed to watch my rehearsals, they made corrections, they helped me outside of that context as well. I feel so grateful for that and, of course, it is as if your idol suddenly appears, he helps you. The reunion has been very nice, because I had seen José and Marcelo, but not all four at the same time.

We saw you last year in various interpretative roles, leading the Compañía Nacional de Danza (CND) of Spain, a group of which you were artistic director for five years, until a few months ago. What did the CND leave in Joaquín de Luz?

A great deal of learning. I think that all experiences teach you, both the negative and the positive. It has been a difficult stage in my life. Having danced in so many places where they love dance, where they are interested, and seeing that in Spain, with the talent that there is, it doesn’t matter, and that they don’t support it so much, is very frustrating. I have had a bad time. In the end, politicians are the ones who make the decision — the CND depends on the National Institute of Performing Arts and Music, attached to the Ministry of Culture of Spain. So, it is a big exercise of restraint, of patience, of adjustment, of resilience.

I love what I do, I have always loved it and if I go somewhere, it is to contribute, but they have to let me, because if not, my nature is not to sit and be passive, without anything happening. They called me to Spain to make a change; I cannot sit and collect a public salary for nothing to happen. For them I have been a thorn in their side.

Of course, there were some very good parts of that stage. Behind closed doors, at the CND, the work has been very good and, as I say, a learning experience. That gives you tools for the next challenge; we will see what it is.

And on top of all that, is there satisfaction?

Yes, totally. The balance is positive, despite everything. What I wanted was to contribute. I hope I have done so at least a little.

What is the next step for Joaquín de Luz?

I have been given the artistic direction of Veranos de la Villa 2025, a festival that has been running for 40 editions, a classic in Madrid. It is very nice. Summer nights in Madrid are very active, the audience is very diverse, from tourists who come to visit the city to older people who cannot go to the beach, and more humble people too. It is quite a big challenge. I not only have to program dance, but also theater, cinema, music of all kinds, circus and performing arts in the street in general. There is a huge range of activities and it makes me a little dizzy, but I think that from time to time you have to allow yourself to feel it. It is good to never stay in your comfort zone. I accept the challenge. We will see.

You are a prestigious figure in the international performing arts scene. How do you see the world of dance as art and market today?

I think that society is reflected in dance. It is difficult for us to be present in that universe today, to convince someone to sit down and watch a show, much more so in the Western world, which has everything, many technologies.

We are spoiled. You open a phone and you are bombarded with information. The new generations look more for instant gratification and that presence and that gift that one can give oneself by sitting in a chair for two hours, without a phone, and letting oneself be carried away to another world, has been lost.

I want to think — I’m a romantic and a quixotic — that that mass appeal will return again. Care has been lost. Nowadays a lot of entertainment is made to be able to reach an audience, but for an artist to reach you it doesn’t take much, what is needed is to do it well. For that, the audience also needs to be committed and present.

When I was going to be a father, I asked myself, “What am I going to leave my son? What am I going to teach him?” In the end, what matters is presence, being present as people, as an audience, as artists. Life goes by so fast, while we are bombarded with information. I think we need to take a break and develop. A dancer is made over time, it is a craft. Nowadays young people think they can dance because they can imitate a jump they have seen on YouTube, and that is not the case.

We are lucky to have the presence of Joaquín de Luz.

For many years to come, rest assured. In one way or another, I hope my body continues to allow me to continue dancing and connecting with those who enjoy what we do.