This is a story on wheels. Although the most famous Cuban automobile Grand Prix may be that of 1958, marked by the “movie-like” kidnapping of the star Argentine driver Juan Manuel Fangio and a tragic accident that ended with forty spectators flying to pieces in the air, the first international automobile competition held on the island took place many years before.

This “Cuban race” of the world circuit took place on February 12, 1905, shortly after the affiliation of the Automobile Club of Havana to the International Association of Automobile Racing, and as a corollary of the passion for motor racing that had been fueling Havana society. It was quite an event, with a large influx of tourists, reporters and foreign photographers, and thousands of curious people along the route.

It is worth remembering that, since December 1898, before the stupefied eyes of passers-by, the first car powered by internal combustion had appeared on the dusty avenues of the capital: a French Parisienne that sounded like a cough was slower than a bicycle and rattled like a collapsible cardboard box. Six months later, the second vehicle arrived — also from France — an eight-horsepower Rochet Schneider owned by the well-known pharmacist Ernesto Sarrá. Owning a car was then a thing for the rich. However now that I think about it, they still cost a fortune and remain a pipe dream for many people.

Cuba, a pioneer in so many innovations and technology, began in the new century to change the reins of the horse for the luxury of the steering wheel.

A product of Cuban nature, those first cars would be recorded in the annals as “fotingos” (jalopies), a nickname given to them by popular speech when they “Cubanized” the slogan of the Ford Motor Company when it launched its brand new “T” model. It turns out that despite the novelty of the three pedals (clutch, brake, and accelerator), the car of the famous American company did not have a starter motor, so you had to push it to start it. The advertising, which indicated in English: Foot in and go, could be translated as a simple “step on it and start it”; but Cubans, with the spark and lexical laziness always lit, ended up putting their linguistic stamp on it, thus the “fotingo.”.

“There were soon magazines, clubs, and associations in Cuba linked to the automobile. And early, very early, car races began. In 1903, Dámaso Lainez, owner of the first service center that existed in Cuba — it was located on Egido Street — called for the first one on the Puente de La Lisa–Guanajay stretch. This race had a peculiarity: the competitors had their respective wives as co-pilots. The winner was Dámaso Lainez, the organizer of the contest,” Ciro Bianchi wrote in his article “Automóviles en Cuba.”

Looking even further back in the rearview mirror of the subject: the first official automobile race that is remembered in the world took place on July 22, 1894, and is known as the Paris–Rouen Horseless Carriage Race. It was organized by the French newspaper Le Petit Journal and was carried out with 21 cars that traveled 126 kilometers to demonstrate before hundreds of eyes the advantages of the modern means of transportation, whose production was just beginning.

Obviously, those first races were not, by any means, like the current ones.

The track of emotions

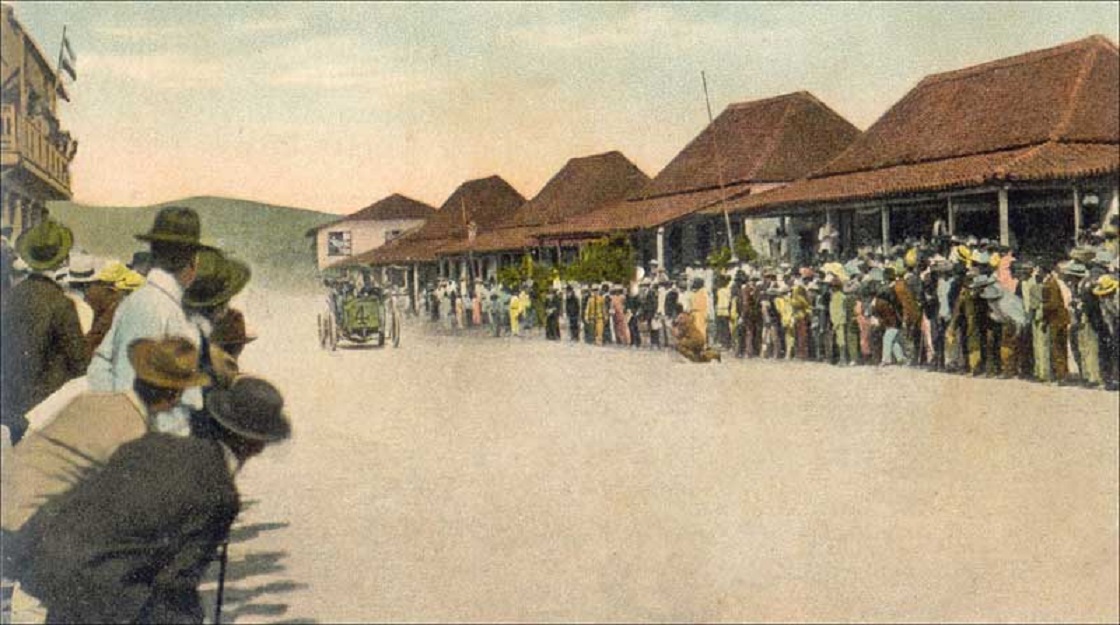

On February 12, 1905, the atmosphere was completely lively, like a town on a fair day. From the early hours of the morning, the public began to move in carriages, buses, and cars along the Marianao road towards the outskirts of Havana. The venue for the competition was set on the picturesque stretch from Arroyo Arenas (current municipality of La Lisa) to the town of San Cristóbal (then jurisdiction of Pinar del Río, today Artemisa), which would serve as an intermediate goal. It was a 158-kilometer route, including the round trip.

For the occasion, a traffic circle and a box were built at the entrance to Arroyo Arenas to accommodate President Estrada Palma, who was attending the event. But neither the overwhelming joy nor the colorful landscape could hide the potholes in the road, which threatened to endanger traffic safety. “It is a pity that the joys of the expedition were eclipsed, in some stretches, by the poor condition of the road. Many potholes and a lot of dust,” described Enrique Fontanills in a chronicle published the next day by the Diario de la Marina.

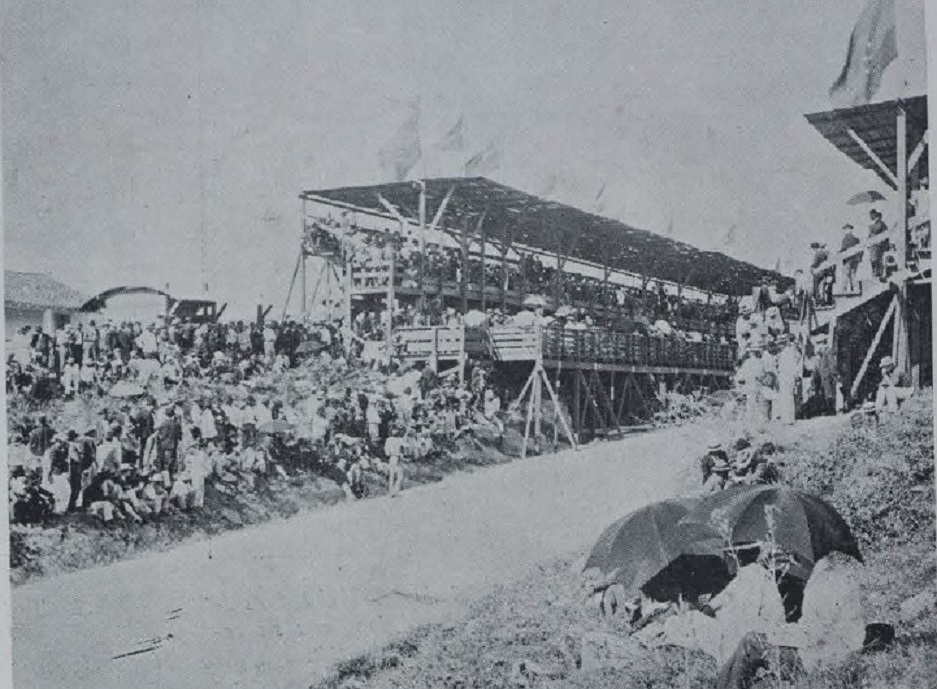

This was not the only botched job that the chronicler noticed: “Over a large area there were wide stands, in the sun and shade, built of wood, without any paint, no decorations, like improvised booths for a one-day party. Those who directed the work had forgotten how easily they could decorate everything with a few hundred palm trees…. Thus, under the sun, protected only by a light parasol, the Havana ladies had to resign themselves to watching the spectacle. There were no other adornments in that place than the flags of various nations waving high above. If there was not enough time to paint, a few hours would have been enough, with a little goodwill, to decorate. That was everyone’s complaint.” We can see that certain problems go back a long way.

In addition to what was reported by the Diario de la Marina, the best note of that day appears in the magazine El Fígaro, which dedicated two issues (February 12 and 19) to a careful graphic and informative coverage of what it described as a “success” [sic]. The atmosphere before the race was captured in the edition of the 12th itself:

“Motor racing is in the news today. The clatter of automobile carriages can be heard everywhere as they prepare to take their lucky owners to the San Cristobal highway to witness the interesting races that will take place today, Sunday. For this reason, Havana has become auto-mobilized; and some in the rich and extravagant automobile, others in the lavish mail coach, or in the serious and graceful vis-a-vis, and many in the democratic family car and even in the popular penny-pinching car, look for a way to go to the obscure town of Arroyo Arenas, where the races will begin. There they will find the elegant and splendid traffic circle that the Association of International Automobile Races has built and from where the great world will be able to watch the races, that is, from there they will see the cars start and then wait… to see them come. To fill the interval there will be bicycle races.”

Of ships and helmsmen

I am not deceiving you when I point out that some of the most accredited sportsmen of the moment came with their respective cars, also among the most powerful of the time. Among the drivers, in fact, were world champions. On the eve of the race, the cars were kept in the Havana Garage, located on Zulueta Street and owned by Mr. Germán López.

The following vehicles were registered for the starting line:

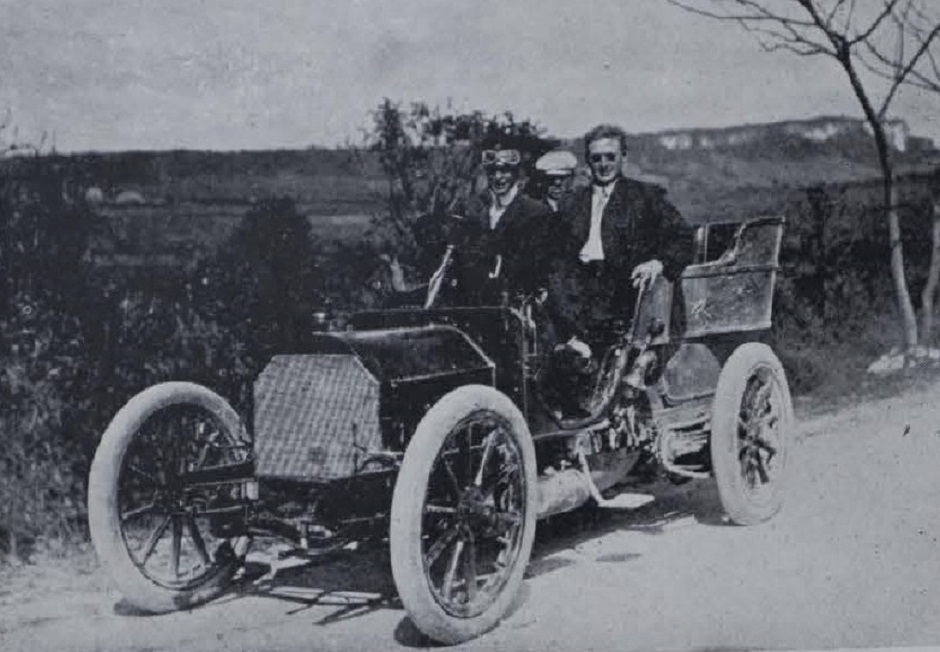

– Renault of Mr. J.S. Miller, from New York. 60 horsepower. Dark blue. Although it is not the largest and most powerful, it stands out for its history of triumphs and lightness. Two years earlier, owned by Mr. William Gould Brokaw, it was the first car to arrive in Bordeaux in the eventful Paris-Madrid race (1903). This will be driven the first part of the route by its owner Mr. Miller and the other half by Joe Tracy, a famous American racing driver of Irish origin.

– De Dietrich owned by O.F. Thomas, of New York. 80 horsepower and four-cylinder engine. Sky blue. Coming from the factory in Luneville, France, it is another powerful car with an enviable record in tournaments, including winning the 50- and 100-mile world races at Ormond-Daytona Beach, Florida. It will be driven by its owner Mr. Thomas and his chauffeur H.W. Fletcher, who will be accompanied by Monsieur Francois Chartier, foreman of the De Dietrich & Cie workshops, who came expressly to Cuba for that purpose. A priori it is one of the favorites to win. Marked with the number 41.

– Mercedes owned by Louis Marx, of Havana. 40 horsepower. Driven by its chauffeur Joseph Birk, who has demanded 5,000 pesos insurance. Navy blue. Number 4.

– Mercedes owned by Mr. Enrique Conill, from Havana. 60 horsepower. Driven by Ernesto Carricaburu, a newcomer in races of this type, and with the mechanic Ramón Martínez as co-pilot. Navy blue. Number 5.

– De Dietrich owned by Mr. Ramón Mendoza, from Havana. 35 horsepower. Driven by Mr. Johns. Number 8.

– Mercedes owned by Mr. Edward Rusell Thomas, from New York. Manufactured in Constanza, Germany, with its 90 horsepower and four-cylinder vertical engine, it is on paper the most powerful vehicle among those present. It has just won the short- and long-distance speed races on the Ormond circuit weeks before. On board will be its owner Mr. Thomas, his mechanic H.A. Robinson, and the professional driver Edward Hawley. Number 6.

In addition, two White steam cars belonging to Mr. Roland H. White and Mr. Augustine Post were presented, as well as a luxurious 45-horsepower Columbia owned by Mr. Miller, intended for low-speed races.

At the starting line

“The Arroyo Arenas traffic circle was packed with a huge audience. It was a splendid day. The sun gave brilliant tints to the spectacle and a strong spring breeze detracted from the heat of the Tropics,” El Fígaro did not skimp on details on February 19, when sketching a watercolor of the development of the competition a week later.

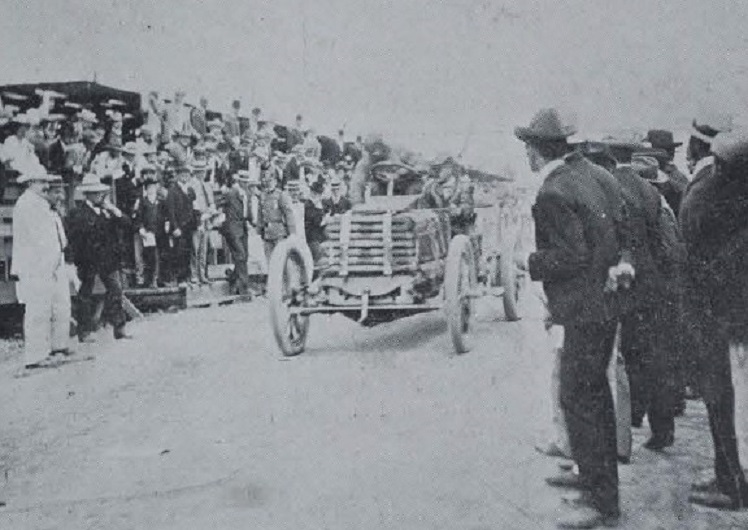

“The dismissing jury,” continues the story in El Fígaro, “gave the order to start at 12:10 sharp. The Renault was in the line of advance and at the Jury’s command it started majestically and as fast as an arrow, disappearing into the horizon a few seconds later. Fletcher’s De Dietrich followed in turn: he advanced with his car to the starting point, shook hands with his wife who was there, and smiled, happy and satisfied, to his friends, as if to say to them: ‘the victory is mine.’ Mendoza, Lainez, Berndes, and Merry, watch in hand, waited for the precise minute, and all gave the order in unison. The De Dietrich started, but after a few steps it stopped like a frightened colt, it backed up, it skidded, it thundered and deafened as if protesting the delay, several Americans approached and pushed it; Fletcher was furious, the mechanic managed to get the valves to work and it finally took off like lightning. In this setback, it lost a few minutes.… Behind the De Dietrich came Mr. Marx’s Mercedes, followed by Mr. Conill’s, driven by Carricaburu, which took off like a feather, and finally, Mr. Ramón G. de Mendoza’s De Dietrich.”

That was how it was then: they left one by one, with a few minutes difference. The list of participants had been reduced to five because unfortunately, the powerful Mercedes of the millionaire E.R. Thomas was out of action due to technical defects suffered when it crashed on the Guanajay highway during the recognition test carried out two days before. However, despite the small number of cars entered, the race was quite lively.

Faced with the setback, experts and bettors reconsidered their favorites, anticipating the other superlatively powerful machine, the 80-horsepower De Dietrich, with the best chance of winning, added to the recognized skill of its driver, Mr. Fletcher. The young Carricaburu did not think in this way. He had faith in his competitiveness and dreamed of making his debut as only the chosen ones of the sport can do. He was determined to take advantage of the slightest carelessness of his rivals and steal time from time.

Members of the organizing committee, assisted by a loudspeaker, occasionally gave an account of the details that arrived through an efficient internal telephone service that connected the different locations along the road where the cars were traveling. Thus the public in the central grandstand, who logically could not see the course of events given the distance, began to imagine in their heads the arrests of the Cuban driver. Surprisingly, and with a bit of luck, Carricaburu left Fletcher’s De Dietrich, which had a flat tire at Hoyo Colorado, on the side of the road, and also managed to overtake Marx’s Mercedes, which had started ten minutes earlier, at Las Mangas.

When Carricaburu entered San Cristóbal, he was informed that he was only two minutes behind the Renault, which was in the lead. At that point, he had no doubt that he should press the accelerator a little more and sharpen his senses to avoid accidents. However, as it would later be known, the referees who were keeping score calculated that by the time he passed the intermediate finish line, the home driver had the race in his pocket.

Checkered flag

The final decision was announced upon returning to Arroyo Arenas, where the crowd went from expectation to delirium when the Mercedes No. 5, owned by Mr. Conill, at that time president of the Association of International Automobile Races in Havana, was officially declared the winner of the rally.

Ernesto Carricaburu, who had never participated in this sport, not only managed to beat the experienced Miller-Tracy duo in their fancy Renault by a minute and a half but also stopped the clock at 1 hour, 50 minutes, 53 seconds and three-fifths of a second, a record that ended up being approved as a world speed record for 100 miles. The average speed of 87 km/h on that rugged and winding road says a lot about the skill of the man behind the wheel.

The Havana City Council was in charge of awarding the winner with the Habana Cup, a work of art created by the famous goldsmith Oscar Pagliery. The regal trophy, 32 centimeters in size, was composed of four parts saturated with silver and gold filigree. With two polished gold handles, the cup itself showed on one side the relief of a car and on the other the Morro Castle; on the pedestal, the trunk of a silver palm tree with leaves carved in green gold could be seen, next to a female figure of Havana with the city’s coat of arms in her hand; while on the base, also made of silver, a card bordered by a laurel branch read the inscription: “The City Council of Havana to the winner of the Automobile Races. — February 12, 1905.”

The extraordinary envoy and minister plenipotentiary of the United States, Herbert G. Squiers, presented another artistic cup from the Tiffany House in New York; Senator William J. Morgan also acted as the main sponsor of the tournament, in his strategy to found a platform for tourist trips to the island.

For their part, the newspaper La Lucha and the commercial houses Palais Royal, Dubic, Borbolla, El Anteojo, and La Casa de Hierro contributed other valuable pieces to reward the winners. Carricaburu was carried in arms like a sovereign of time and space, while the Municipal Band played the Bayamo Anthem from its stand.