Bacardí knew little, if anything, about beer. He did know about the “secret formulas” for producing that spirituous prodigy called rum. But that didn’t stop the stubborn Enrique Schueg, then president of the eponymous corporation, from his feverish idea: to expand into the world of beer. The audacity to embark on new ventures is in the DNA of this long-established Santiago de Cuba family and drives them day after day to enhance their wealth and legacy.

Thus, in 1927, the Bacardí company burst onto the national market with a superior offer, Hatuey light beer, labeled in tribute to the hero of the indigenous resistance, whose martyrdom became an inspiration for Cuban nationalism. “He who invented Hatuey beer was a wise man,” Plato himself would have thought if he had had the chance to down one of those bottles.

The brand-new industry was built in the humble neighborhood of San Pedrito, on the premises of the former Santiago Brewing Company, founded years earlier by engineer Eduardo J. Chibás (father of the orthodox politician) and purchased by the Bacardí Rum Company S.A. around 1920.

In the following years, Bacardí renovated the factory by investing in new tanks, drilling a well to improve the water supply, installing an ice plant, and hiring a German-born master brewer from the United States to supervise the brewery. Quality was the key to success.

Like the effervescent foam of that golden liquid, the Hatuey beer business quickly grew promisingly. Once again, in deciding to diversify their production, the Bacardís had acted with wisdom and futuristic vision.

By 1947, all the breweries in Cuba combined produced 81.4 million liters that year, a quantity lower than the growing demand of the drinking clientele — and also influenced by the consumption of U.S. tourists — so it was necessary to import 428,000 24-bottle cases.

Faced with this growing thirst, old Schueg — considered the true genius of the family company — sensed that the time had come to open a branch on the outskirts of Havana. It was the second brewery to carry the Hatuey brand; a third, the Central Brewery, was established in 1953 in Manacas, then the province of Las Villas.

With this manufacturing trio, Hatuey became a heavyweight in beer production and monopolized half of the supply of this popular beverage, at a time when the quality of Cuban beer was so high that foreign counterparts failed to penetrate the domestic market, despite their attempts.

No one could compete in price and quality with local beers. This national brewing tradition, born way back in 1888 with La Tropical by the Spaniard Martínez Ybor, has stagnated in recent decades due to a lack of financing.

An emerging industry

18 kilometers from the city center, a picturesque farm located in El Cotorro was chosen as the location for the Modelo Brewery, primarily for having underground springs connected to the Santa María del Rosario spa. These waters were considered miraculous ever since a legend spread in the social imagination that their baths had cured the Count of Casa Bayona of gout, back in the distant year of 1727.

Although most of the few references that can be found on the subject on the internet and social media inaccurately repeat that its opening occurred between 1946 and 1947, it was actually inaugurated on the morning of July 22, 1948.

These were the “authentic” days when Prío sought to dethrone Grau San Martín from the presidential chair and the streets were ruled by Meyer Lansky-style gangsterism, while a new season of detective Chan Li Po was broadcast on the CMQ circuit.

Perhaps the origin of such inaccuracy regarding the founding date is due to the fact that the commercial entity was organized on June 24, 1946, according to Guillermo Jiménez in Las empresas de Cuba. 1958.

The first shareholders came from the parent company, with its president, José “Pepín” Bosch — Schueg’s son-in-law — and its vice presidents, Jorge Schueg Bacardí and Joaquín Bacardí Fernández-Fontecha, who had graduated as a chemical engineer from Harvard and completed a master’s degree in Copenhagen. As a pioneer in this type of fermentation within the family, he ended up being known as “The Brewer.” The manager was engineer Carlos Hevia, the same man who had been president for 72 hours in 1934 and an old friend of Pepín Bosch.

The truth is that even at the beginning of 1948, the Modelo was still nothing more than a bulk among scaffolding. Under the headline “Una industria que nace,” the January 25 issue of Bohemia magazine noted: “A few meters from the Central Highway, the new factory’s modern five-story structure rises. According to what we were told, it should have been in production several months ago, but due to a imbalance in the supply markets for machinery and construction materials, its completion has encountered numerous obstacles, almost all of which have now been overcome. The entrepreneurs expect the product to be in the hands of consumers within three or four months.” The investment, the report stated, was around half a million pesos.

Indeed, by the summer of that year, the capital’s press — such as Bohemia itself and the Diario de la Marina — announced with great fanfare that the ribbon-cutting of the factory’s inauguration had been carried out in a solemn and lucid ceremony attended by the honorable President of the Republic, prominent figures, members of the commercial and industrial sectors, and a good representation of Havana society.

Modelo Brewery S.A. was an industrial colossus dedicated to the production of beer and malt drinks, combining the most modern architectural and industrial elements of the time. Designed by architect Enrique Luis Varela, the majestic building combined beauty and functionality, with adaptations designed to manage the conditions of Cuba’s tropical climate.

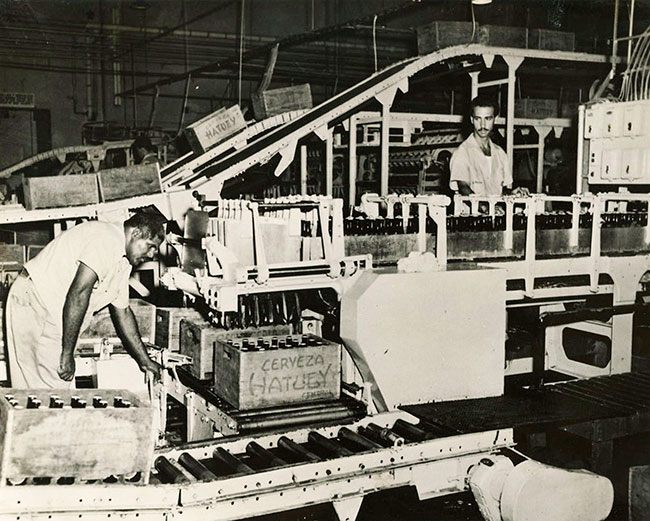

The four-story circular water storage tank, the enormous barley tanks, the comfortable cellars, and the monstrous machine with intricate gears where bottling took place with astonishing automation were striking.

As if that weren’t enough, the factory boasted a state-of-the-art wastewater treatment plant and attractive gardens. Royal palm trees abounded within its boundaries, and the largest Cuban flag in the country hung on the façade of the main building.

Beyond the cutting-edge technology and exclusive raw materials, the scientists and workers, organized in a tiered system, were required to adhere to strict control and innovation measures during the production process to ensure high quality standards. They wore custom-made uniforms, with different colors corresponding to the different work areas, and earned salaries considered high for the time, in addition to receiving other specific benefits.

True to its name, it was really a model brewery. It was undoubtedly one of the symbols of the country’s industrial development during the 20th century. Its main challenge was ensuring that the Hatuey brewery in El Cotorro, which was intended to meet demand in the western provinces, was “identical” in aroma, flavor, and color to the original from Santiago de Cuba. It is said that no one could notice the differences.

The old man and the brand

You could ask Hemingway. A hardened drinker of Constante’s daiquiris at El Floridita, Papa became the Bacardí Company’s best publicist. In his novels and writings, where he recreates his experiences on the island, mentions of the company’s products appear:

“I’ll give you the belly of a big fish,” the old man said. “Have you done this for us more than once?”

“I think so.”

“Then I’ll have to give you more than the belly. You’re very considerate.”

“He sent two beers.”

“I like canned beer better.”

“I know. But this one comes in bottles. Hatuey Beer. And I’ll return the bottles later.”

“That’s very kind of you,” the old man said. “Shall we eat?”

This passage can be read in The Old Man and the Sea, which earned the U.S. writer the Nobel Prize in Literature (1954). Precisely to make the most Cuban of Hemingway’s books accessible to everyone, in its March 15, 1953, issue, Bohemia magazine published the first Spanish version — translated by Lino Novás Calvo — of the famous novel.

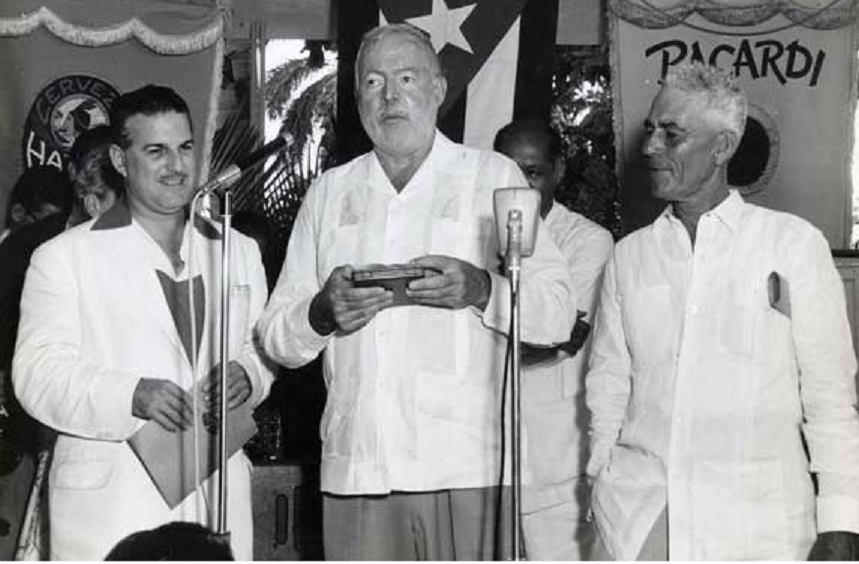

For one reason or another, the Bacardi Company wanted to reciprocate with a “empathetic tribute.” To that end, on August 13, 1956, it hosted a luncheon for the writer and his wife, Mary Welsh, at the Modelo Brewery; coincidentally, located not far from Finca Vigía.

It is said that Hemingway — who had previously refused to attend similar celebrations, even at high-class clubs — accepted the invitation because they allowed him to bring his fishermen friends. These, all weathered by salt and hard work under the sun, joined him at the head table.

Held in the gardens, the banquet was described in great detail by Guillermo Cabrera Infante in “El viejo y la marca,” a chronicle published in September 1956 in issue number 5 of Ciclón, the magazine founded by José Rodríguez Feo after his dispute with Orígenes and Lezama.

“Hemingway looked like one of those monuments next to which everyone takes their picture. This time, the monument was moving. Wearing a white guayabera shirt, graying, his face beaten by time, he appeared prematurely aged and with a kind of tiredness in his gaze,” Cabrera Infante describes in his story.

The menu consisted of roast pork, tamales, boiled yuca, rice with red beans, and a well-stocked bar. Needless to say, rum, cocktails, malt drinks, and cold beers flowed like overflowing rivers to the beat of cha-chas and guarachas played by a trio on an improvised platform.

Fernando Campoamor, a journalist specializing in covering the social scene, acted as master of ceremonies and gave the floor to the guest of honor. Holding the medal in his hands, the awardee read a simple note in his particular Spanish: “I am very grateful and moved by this undeserved tribute. I have always understood that writers should write, not speak. Therefore, I now wish to donate the medal I received for the Nobel Prize in Literature to Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre, patron saint of this country I love so much.” He presented the award to Campoamor, who thanked him on behalf of the Cuban people.

What the wind left us

Like a sugar factory in a sugar mill town, the brewery governed the life of the town. Many locals would wake up to the brewery’s whistle at seven in the morning, or children would know it was bath time when the siren sounded again around five in the afternoon. It is even said that the town used its water wells, and that the production process was explained as a model in secondary schools. It also had an amateur baseball team.

It was, of course, a formidable source of community employment. To give you an idea, in July 1949, the first anniversary of the factory, 210 workers and employees — not including sales agents, vendors, distributors, and carters — were employed there, enjoying average wages of between 7.65 and 10.27 pesos a day. This, a Bohemia reporter affirmed, allowed them to live fairly comfortably. Furthermore, at Christmas, Epiphany, or other commemorative dates, the workers’ families could enjoy banquets and celebrations in the gardens or the large picnic area, fostering a close relationship between the factory and the home.

The workforce would increase in the following years as production capacity multiplied. By the mid-1950s, the Modelo was producing an incredible 10 million bottles of beer through its mechanized lines, according to an advertorial by Mario Kuchilán in Bohemia on July 23.

On October 14, 1960, it was nationalized and renamed after Guido Pérez, a distinguished patriot from El Cotorro who had worked at the factory and was one of the local leaders of the 26th of July Movement during the April 9, 1958 strike, for which he was assassinated.

Over the decades, the industrial complex deteriorated. The Modelo Brewery was back in the news last Friday, April 11, when a powerful fire broke out in an old icehouse that burned for twenty hours before being extinguished, further ruining the facility. Of its young years, old traditions and heritage values, nothing remains but nostalgia, shadows and ashes.