Issac Delgado is a distinguished figure in Cuban popular music. He created his own group in 1991 and established a very personal stamp. He had previously been part of groups such as the Pacho Alonso Orchestra and NG La Banda.

“El Chévere de la salsa,” a nickname that also came to him in the early 1990s and which he has not been able to shake off, was part of that wave of musicians who flooded Cuba and the world with the timba boom, although his style was always distinct, especially because it leaned closer to salsa.

For many, Issac is simply the elegance that timba can also possess, that perfect blend of banter, the street, the people and exquisite taste, the cadence, the sweetness in his voice.

More than four decades of work cannot be summarized in a single interview, especially when Issac Delgado continues to constantly make headlines.

Just a few days ago, he released his new album, Mira como vengo. Just a few weeks ago, he made headlines by being the most awarded artist at Cubadisco 2025 for his tribute album to the 100th anniversary of Sonora Matancera.

Summer is here, and music lovers know that Josone awaits us, the event with which Issac has once again transformed Varadero into a major cultural center.

Talking to Issac Delgado is a multifaceted journey, which as an excuse we began with his new album, which arrives six years after his previous release, Lluvia y fuego, in 2019, although that doesn’t mean the artist has been inactive — quite the opposite.

Issac lives with his feet on the ground, observing and absorbing his surroundings, reality and, of course, being a part of it. The title of his new album is a call to attention, and that’s where I wanted to start.

How is Issac Delgado coming?

Issac comes with new music, with new insights from how we worked on this new album, which was truly a challenge because we recorded, as always, between several waters. We made part of the album here in Cuba with musicians who don’t usually record with me, who are musicians from the orchestra, and the work they’ve done is excellent; and with Alain Pérez again, after many years of working together as well. I wanted this project to be very intimate and include part of my family. I’m very happy about what’s happening.

“Mira como vengo” is a song that’s been in your repertoire for over a decade. Wasn’t it a risky move to revisit it to present something new?

That song is co-written with Manuel González “Manolín,” and we had written it to be performed with representatives of urban music, with an urban style. We were already thinking about that and didn’t know it would have such a strong boom in Cuba.

So I said, well, this is a song we can do in my normal style, more salsa, more danceable, and we’re super happy because people already had the idea or the melody itself, and when they see it in this style, we realize that the music is one and that it can take us to different environments depending on what we want to convey to the public.

The timing of the album’s release wasn’t perhaps the most propitious. Why did you choose that date?

The day we put the album on the platform, I was simultaneously with many exponents of this same music; Alain (Pérez), Pedrito Martínez, and not only on our part, but other colleagues in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic have also released albums, and I think it was the best thing. It’s been super interesting because we’re alive, this music is alive.

I think this album gives me the opportunity to return to a faster pace of for young people and all the people who have followed me all these years. I think it’s recapturing a path in this same form of musical expression that I’ve had throughout my career.

The release of this album on social media was accompanied by a message announcing a more personal production. What’s special about this album in that sense?

I feel super happy because all the songs relate to me. I always try to find authors who have something to do with me, and who generally write songs thinking of me. I had my own pieces that were specifically for a rumba album, which was a little easier for dancers. We started composing for that in the middle of the pandemic. I also started experimenting with my children, with some elements we wanted to add, specifically because of my usual sound, which is a mix of timba, salsa, and Afro-Cuban music.

We also wanted to pay tribute to Havana. I’ve sung a lot about the city of Havana, since my beginnings with Pacho’s orchestra, and Alina Torres gave me the song dedicated to San Cristóbal, which is the final track on this album. So all the songs have a meaning, and the album in general because it was made at a very specific time in my life.

What happened?

I had a major family problem, and I completely stopped. The family, everything and the album came to a standstill. Today, we’re celebrating life with this album. Celebrating all the beautiful things that have happened to us in the last eight months.

Why so much time between one album and another?

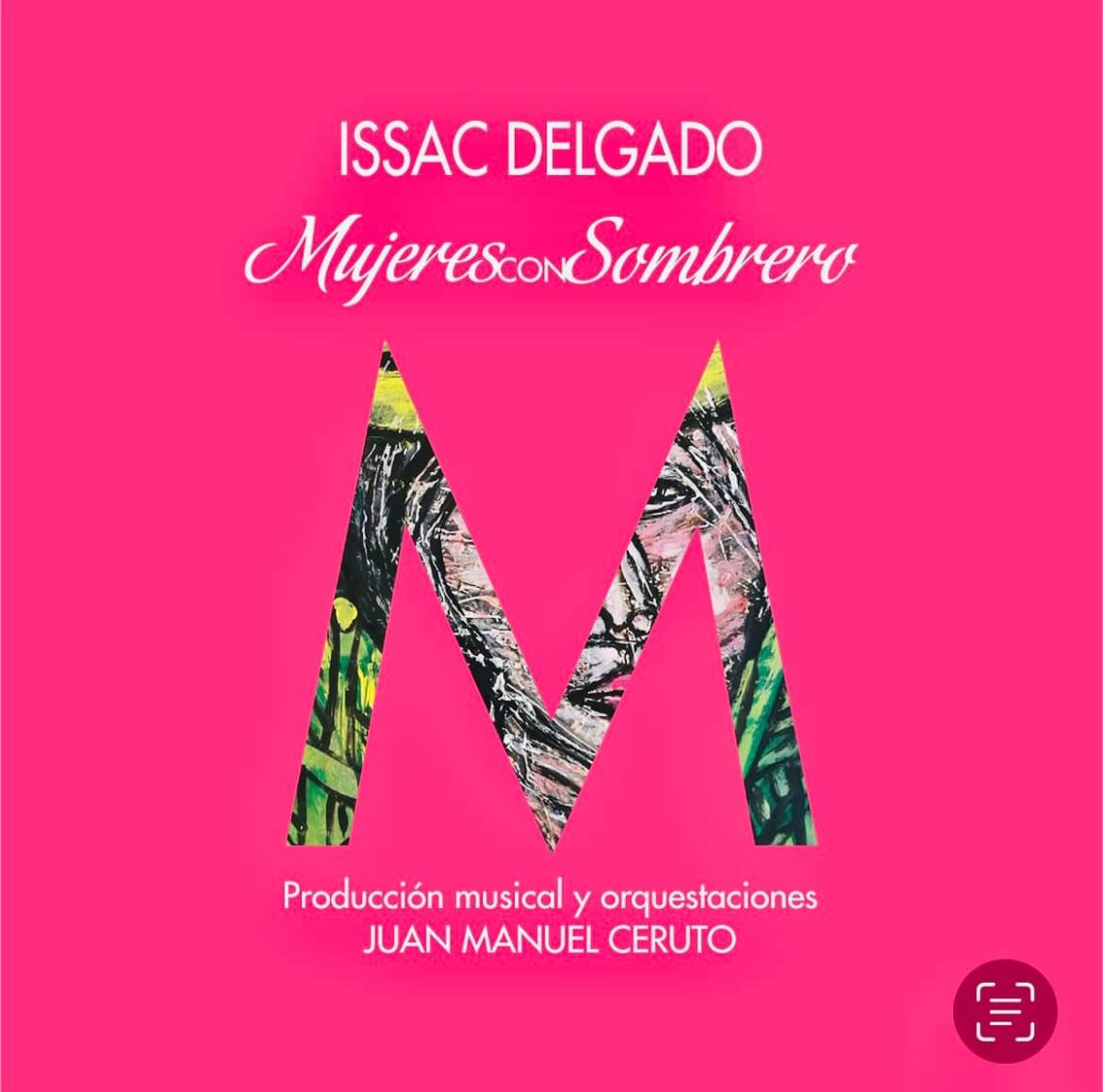

In the midst of these six years without making an album, especially one that was so danceable, we were making an album with the Aragón Orchestra, which won a Grammy Award. We made an album with Silvio Rodríguez’s music called Mujeres con Sombrero, and then we made the album for the 100th anniversary of Sonora Matancera. In between, I’d made some singles, the singles that one makes. So, it’s been six years of work.

The album for the 100th anniversary of Sonora Matancera just gave you the chance to be the most awarded artist at Cubadisco 2025…

A huge surprise. For us musicians, from anywhere in the world, the Cubadisco Fair is incredibly important, primarily because those behind it are all established musicians, with different ways of thinking and different ears. Furthermore, there’s almost always a lot of sincerity here because they know we’re very critical, so they’re awarding the music, not the person. This year they gave me the award for best producer, and it’s significant that it was for a tribute album to the 100th anniversary of a group like Sonora Matancera.

It’s a challenge to make an album like this, to achieve that sound that came from Matanzas, in that province where Arsenio Rodríguez, Celina González, Saldiguera, Virulilla, Los Muñequitos de Matanza were born — the whole complex of rumbas, of the folk music that was formed there by a student group in the 1920s, which later evolved into the sound of a “Sonora” and then flooded the world, and which hadn’t really been recognized in Cuba, as I think it should have been. That’s a music that should have been on the agenda for a long time; I didn’t discover anything. The only fear I had was not capturing reality, and I think it’s there on the album.

What was your idea when making that album?

My idea was to bring that music just as it was played. I was lucky to work on this with a young man, but a son musician at heart, Maikel Dinza, who also knew how to understand what I wanted and transcribed the music. Obviously, we added, and he also added, things of our own, because a hundred years later, the music can’t sound the same.

What’s new in making this music is that today in Mexico, Colombia, and almost all of Latin America, it still sounds like it did on the first day because they have daily Sonora Matancera programs.

The salsa movement that came later was supposedly said by many connoisseurs, students, music lovers, and salsa lovers to be the Matancerization of popular dance music throughout the Americas. So, in fact, all the hits that continued in Venezuela, Colombia, almost all the hits of those groups had an element of the Sonora Matancera repertoire, and every time I go somewhere I learn something new because what I did was enter that world, talking to some musicologists and some music lovers, who gave me information, even for the repertoire.

It was very difficult because there are so many artists and it’s a group that was transgressive, because there were eleven women singing in the Sonora Matancera. Given the machismo that exists in dance music in Latin America, that’s very important.

So I’m happy and content that we were once again presenting authentic Cuban music. From a city that represents art for us because we call it the Athens of Cuba. Sonora Matancera forever. I think we’ll continue working with that.

Before the Sonora album, Mujeres con Sombrero came out, with songs by Silvio Rodríguez, which also won several Cubadisco awards, but it didn’t get much promotion…

It’s an album which we practically didn’t promote. It’s on the platforms, and it’s an album that has a lot of meaning for me because it’s my first album sung with a symphony orchestra, with impressive arrangements by maestro Juan Manuel Ceruto, who is also another essential part of my career.

He challenged me to write Silvio’s music. Silvio’s work is immense. First, because of the lyrics, and second, because he creates songs that are very difficult to interpret and take out of their context, because he writes them for himself.

We were fortunate to have the Mozarteum, which is one of the symphony orchestras with the highest musical quality and that takes on any challenge. That was something that topped this album.

Ceruto’s arrangements, and I asked him to make an album with our seal, that is, that Cuban percussion have a prominent role, that Afro-Cuban elements would be felt, but completely symphonic. I chose the songs that I thought would work for me or that would be the best for me. We worked with top-level musicians like Gastón Joya and Rodney Barreto.

Silvio gave us his blessing, his approval to make this album. And the anecdote was interesting. I told him he had to do a song with me, and he said, ‘But look, the condition I’m setting is that we don’t make a music video.’ And I said, ‘Well, we don’t make any music videos.’

We were in the middle of the pandemic, and people didn’t want to get together too much or expose others. I have some photos of the orchestra, forty-something musicians, all wearing masks. But the experience was immense.

So, why not give it more visibility?

We wanted to wait until the whole pandemic thing was over. And we kept putting it off, then other jobs came along. The other thing is that putting together a concert is very difficult, bringing together forty-something musicians from a symphony orchestra, plus a backing track. It’s very difficult to rehearse that music. I think it’s all been a problem of connections to get us together.

But that album, I think it will remain forever, because it’s timeless. We can present that album at any time. I hope it won’t be too long before I can do justice to what we created with so much love, to such beautiful music that many people don’t know. I think I’m taking advantage of the opportunity for people to hear the album Mujeres con Sombrero, which is a tremendous gift for all those who love good music.

Perhaps without intending to, this was the period in which you most deeply immersed yourself in the work of other greats of Cuban music. What does this experience leave you with for your own work?

I think that’s what made me want to do something for my old friends.

In 2018, you created the Varadero Josone Festival, which will reach its fifth edition this year due to the pauses imposed by COVID-19. How did you manage to find the seal that would distinguish an event within the vast network of musical events in Cuba?

Josone is a festival I always had the idea of creating. You spend your work time, when you go abroad, at festivals that are very specific. In Cuba, festivals are massive, but they have like six or seven venues; all the festivals are immense. And I wanted to do something like when the Jazz Festival started, which was only at the Casa de la Cultura in Plaza, but now it’s a gigantic festival. I wanted to create a boutique festival, in the sense that it’s captivated in one place, so that everyone can find everything there.

They gave me the opportunity to enter a tourist destination like Varadero, a beach resort that always sells sun and natural beauty, to sell music and culture, to find another concept where different musical genres come together.

Since the first festival, we’ve never discriminated against any musical genre. I don’t think there is another one today, and in all the years the festival has been running, that’s so inclusive.

We’ve created a festival by experimenting, giving it access to almost everyone who can be there, because it’s truly a festival for tourism, but national tourism, which people make a mistake about. Tourists are both national and international, because people who go on vacation, even if they’re in a tent, are tourists.

People have embraced the festival and come from Camagüey, Villa Clara, Matanzas itself, from all places near Havana, from everywhere. In other words, little by little, we’ve gained a following and also brought young talent to the forefront.

People go and lie on the grass and walk around. In other words, it’s a place that has a great capacity to bring together diverse audiences with different tastes. I’ve met people who went there looking for urban music and came across the Orquesta Aragón, and they’ve told me that was the best thing about the festival. I think that’s what makes this festival different.

What’s going to happen this year at Josone?

We’ll have the festival from August 25 to 31. Impressive talent has always come from outside Cuba, and this year will be no different.

This year we have a special for DJs who come to play Latin music here, and just as we always have Cuban pop, the ones who have always been there. People say, ‘But will Van Van be there again? Will Maykel Blanco be there again?’ Yes, because people want to spend time with them every year. And that’s what the dancing public has brought.

I’m now leaving for the European tour and coming back, joining the work team. Although there have been changes this year, the production itself is the same as it was with us, and they know the festival very well.

There are always changes, always problems. We face all the problems there are, with electricity, the gen set, everything. But we do it because I believe that’s what it’s all about, being able to bring people entertainment and our music, our art.

How does Issac maintain the essence while remaining innovative in his offers?

The important thing is to try to maintain one’s seal, but not stop listening to what’s happening around us. The foundation is Afro-Cuban music. The foundations are already set by all these people who have left behind a music that will last forever, completely unperishable. What we have to do now is merge it with what’s playing today. More than anything, it’s the sounds that have changed a little.

Are you referring to the impact of urban music?

When people ask me about what’s happening with urban music in Cuba, I say it’s the same guaguancó, but electronic, and with the banterings.

I think we’re going back a bit to the 1990s, when there was the Cuban timba boom. It’s happening again right now, but with new sounds, with new exponents, kids who have to be followed, you have to live alongside them.

Some of us have approached them, others have incorporated some of those kids, because there’s also a mutual respect. I like it because of my children, who have always been part of that movement, and I think that based on that I’m very clear that it’s not out of place to be able to join in or incorporate new sounds into my work. And that’s what I’ve been doing, and this album is part of that.

The changes aren’t just in the sounds, but also in the ways the music industry operates today….

Sometimes people don’t understand that when you make an album, you leave a lot of songs unfinished. If you don’t make an audiovisual, if you don’t have all the necessary elements, the journey isn’t complete, because today, without audiovisuals, it’s very difficult for everyone to understand the world because it moves so fast and is more visual than auditory.

The music that’s heard today, for the most part, is urban music in every country in the world. It’s not just the music of Cuba’s reparto rhythm, but urban music in general. They’re used to having a new video every two months. We were going at a different speed. We’ve had to adapt. I tell my children that I’m still analog, but we’re really in the digital age and you have to adapt.

Today we do the promotion, but luckily, traditional media is still the most important in all parts of the world. When you’re going to do a media tour anywhere in the world, in North America, South America, Europe, you have to use traditional media, which is print media, radio, and television.

It’s mandatory because there’s an audience that doesn’t go out to see concerts. There are millions of people who only have that reference, or not only that, but the most important reference is those media, which are also digital, not analog. For example, a television show you make immediately goes on YouTube.

Despite this urban music boom, young people are also emerging who are committed to timba and popular dance music in general. Do you have any advice for them?

You have to believe in yourself, knowing that you’re making the product because you believe in it. Music is very difficult. There’s a saying by maestro Revé that music is treacherous. But no, music really comes from effort; it only betrays you when you don’t believe in what you’re doing.

So, to all the people who are making new music, I urge them to keep working, to have faith that there’s always someone who will notice their work. And it’s about perseverance; you can’t achieve everything overnight. Years are degrees, and that’s what has given us the opportunity to remain in popular favor, especially when it comes to this music that belongs to the common people.

Why has Issac always returned and is he still in Cuba?

To be able to create what I do, I need the people here. I need to hear their bantering, that’s for the professional part. I’m lucky because I come and go making my music.

On a personal level, I buried my mother here; my whole family is here, and I need them. And because of family issues, this is where I was able to treat my daughter for her medical condition — it’s the first time I’ve said this. I don’t talk about it, but this is where I found the people who cared for her for years, and I’m incredibly happy. I’m incredibly grateful to those doctors, to other people who weren’t specifically doctors but were able to keep her well, and now I’m incredibly happy. We’re all happy.