1910 definitely had a very long tail. Literally, many people’s hair stood on end when, in the spring, Halley’s Comet began to circle the Earth with its stalking trail, like a dragon’s tail. It’s no coincidence that the star — documented for millennia — has transcended as the most iconic of its kind in all eras; after all, it was the first whose reappearance was predicted and the first to be photographed by a spacecraft. But the aforementioned year brought with it a mass hysteria of memorable proportions — similar to Orwell’s War of the Worlds — which we remember as an example of what happens when ignorance and superstition are capable of altering the course of history.

According to scientific studies, the first reference to this celestial body dates back to a record by Chinese astronomers in 240 BC, although there is speculation that a “fireball” sighted in Greece between 467 and 466 BC could have been the famous traveler. The Bayeux Tapestry, a medieval work from the mid-11th century that chronicles the Norman conquest of England, is said to include a representation of Halley’s Comet in its embroidery. It is also thought that its transit in 1301 may have inspired the Star of Bethlehem that floats in the painting The Adoration of the Magi, painted by the Italian Giotto around 1305.

For a long time, ignorant inhabitants of the past considered comets to be intergalactic pirates or black heralds that portended wars, deaths or cataclysms. Of course, the comet in question did not escape the stigma, not even when the English astronomer and mathematician Edmond Halley (1656-1742) — who gave it his identity card and named it after him — proved that it was not a punishment from the gods or anything supernatural, but a space object moving normally in its orbit.

In 1705, Isaac Newton’s favorite student, drawing precisely on his teacher’s treatise on gravitation and planetary motion, noticed similarities in the reports of three bright comets that crossed the skies in 1531, 1607 and 1682. In a bold prediction, Halley suggested that, rather than three, it was the same comet that came and went on a periodic basis every 75 or 76 years. Based on this deduction, he predicted the comet would return in 1758 and, although he didn’t live long enough to see his dazzling prognosis appear in the firmament, he was right.

Mark Twain, whose life was incredibly framed by the star, was right too. In 1909, the famous U.S. writer declared: “I came into the world with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It comes again next year and I hope to go out with it.” On April 21, 1910, as Halley’s comet passed with its whitish plume across the night sky, Mark Twain died of a heart attack.

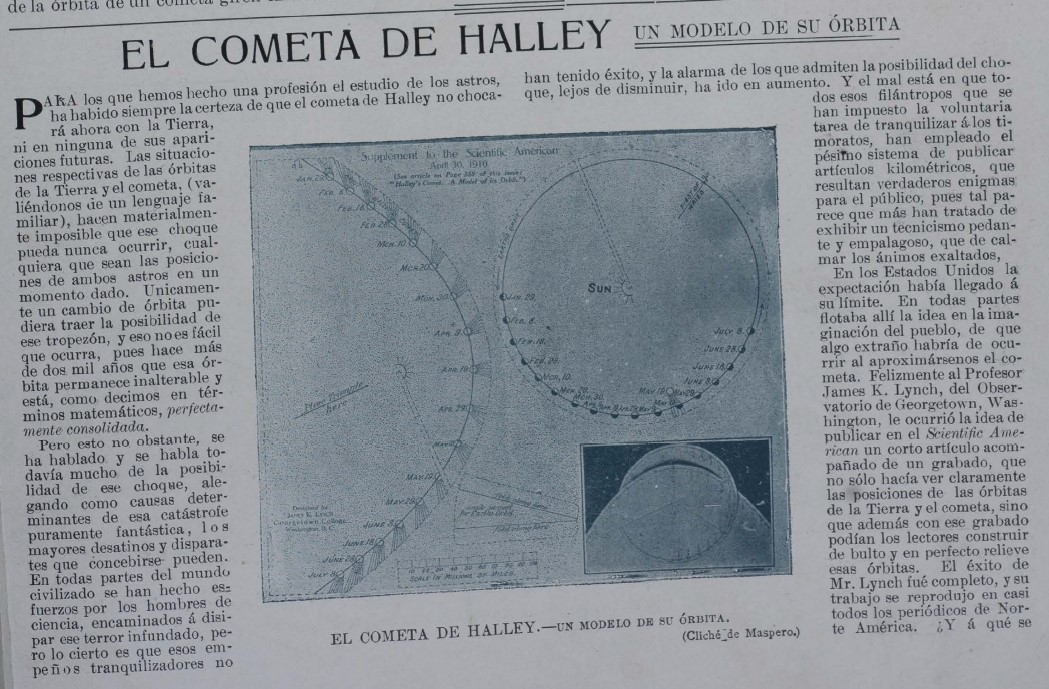

At the beginning of the 20th century, science had advanced by leaps and bounds, and astronomers, equipped with better telescopes and means to scrutinize the solar system, had done everything humanly possible to demystify comets and demonstrate that the famous comet was simply what they all are: a rocky nucleus covered in ice and dust that flies through the cosmos in an elliptical orbit, following a predictable and disjointed rhythm. This helped banish fear and superstition from the collective psyche. Or so it was believed, until 1910, when the fireball arrived, suddenly breaking the monotony of Earth, and the press launched a catastrophic prophecy.

Flammarion’s phlegm

Barely had the year begun when the newspapers came out trumpeting a story that — an editor’s treat? one might ask — delighted a credulous and timid public: between April and May, Halley’s Comet would pass, whipping its 50 million-kilometer tail so close to Earth that its vapor could graze it with a force capable of knocking it off its axis and showering it with a cascade of phosphorescence and space dust that would poison the atmosphere and boil the seas. But not even the most seasoned reporter could come up with a more dramatic explanation of the presumed lethal “tail lash” than the dissertation of the conspicuous Flammarion.

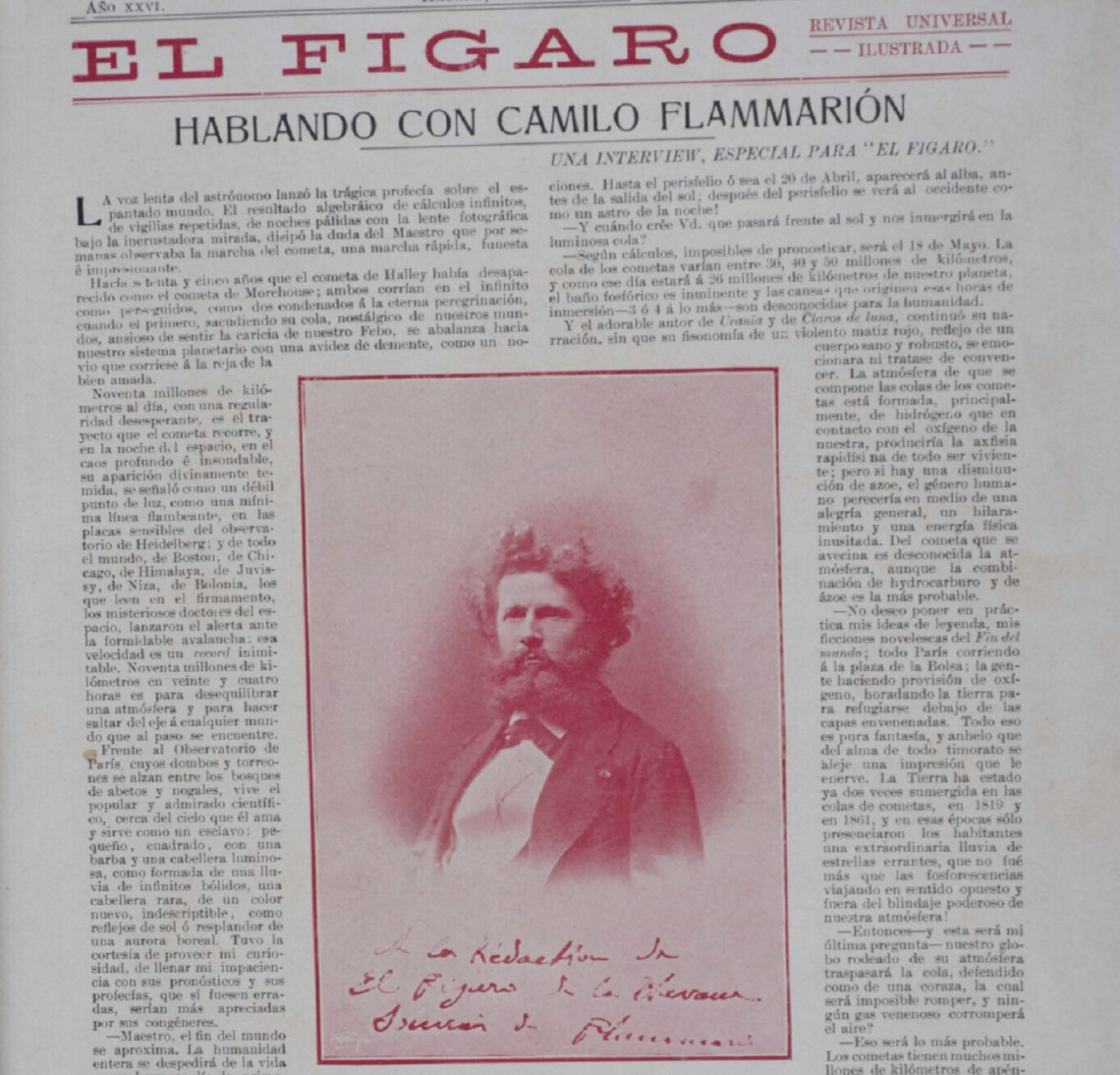

Camille Flammarion was a passionate French astronomer and intellectual of worldwide renown — the Carl Sagan of his time, he has been called. He was also a wealthy and eccentric man, a spiritualist, a science fiction writer and the owner of the magazine L’atmosphère: Météorologie Populaire. Not wanting to waste a single minute, Flammarion moved in across the street from the Paris Observatory itself, whose domes and turrets soared above the fir and walnut forest that bordered it. There he would spend weeks awake, scribbling endless calculations, searching for signs in the chaotic and cryptic firmament, probing with his lens that reflective point that was approaching in swift, impressive motion, hurtling, after its aphelian night, with the “greed of a madman” toward the arms of the sun.

At the same time, another headlong race was underway among newspapers around the world, rushing to extract statements from the doctor of the heavens. The Cuban El Figaro was no less so, landing its own page featuring the star scientist, who “lives close to heaven,” with a small, square build, a “beard of light, as if formed by a shower of infinite meteors,” and “a strange head of hair, a new, indescribable color, like reflections of the sun or the glow of the aurora borealis.” This is how Santiago de Cuba journalist Francisco García Cisneros described him in great detail in his interview with Camille Flammarion.

“Master, the end of the world is approaching. All of humanity will bid farewell to life on a beautiful spring day.”

“That’s a premature prediction. Comets are so erratic! Any whim makes them change orbit,” Flammarion responded, wrapped in the rhetoric of his reputation and the phlegmatic voice of the wise man; clarifying, of course, that it would be a magnificent spectacle and that the comet would appear much more radiant than on its previous visit.

“And when do you think it will pass in front of the sun and plunge us into its luminous tail?” the journalist insisted.

“I don’t wish to put into practice my legendary ideas, my novelistic fictions of the end of the world: people stocking up on oxygen, boring into the earth to take refuge beneath the poisoned layers. All of that is pure fantasy and I long for the soul of every timid person to be shaken free of a nerve-racking impression. The Earth has already been in the tails of comets twice, and the inhabitants only witnessed a shower of wandering stars, outside the powerful shield of our atmosphere.”

“So our globe will pass through the tail, defended as if by an impossible-to-break shell, and no poisonous gas will corrupt the air?”

“That’s most likely.”

Flammarion concluded directly and concisely, his red-tinged face showing no hint of emotion or hesitation. Extending his wide hands, he said goodbye to the Cuban reporter, “still smiling and fixing his little gray eyes on the sky, as if saying a very affectionate good morning to our next guest: Halley’s Comet.”

The cometary week

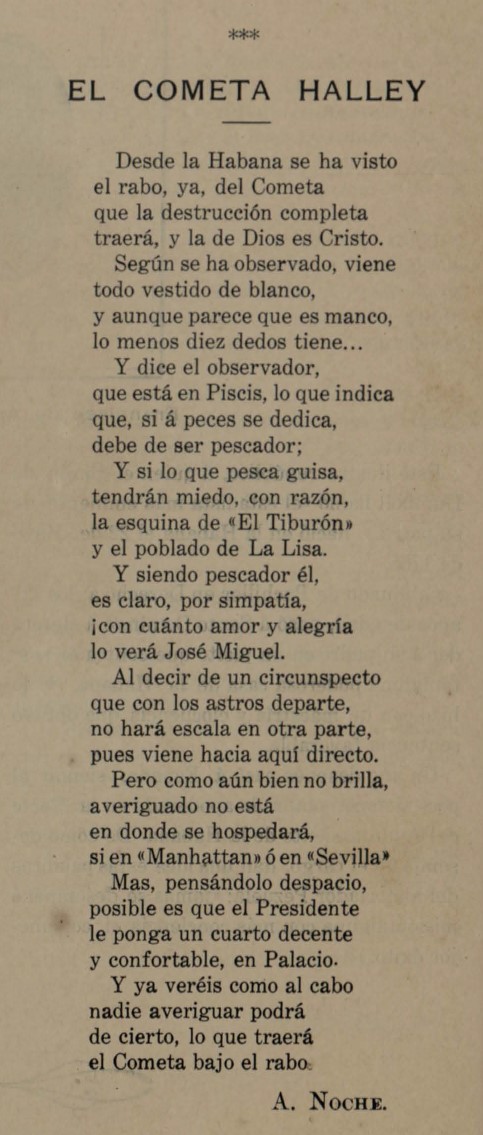

Four months later, when the star seemed to cast its ghostly silhouette over Cuban heads, many had forgotten having read Flammarion’s arguments and his call for composure in Le Figaro on January 23, 1910. Instead, giving more credence to the theories of disaster, they fell prey to horror and bewilderment.

The date for the comet’s passage between the sun and Earth’s surface was set for the night of May 18-19, 1910. How many people were able to sleep? Curiously, the main focus — that is, the greatest fear — was not on the nucleus, but on the tail, loose and wide like white hair. The opinion had spread that, upon receiving intense solar radiation, the comet’s tail — made up of gases and frozen particles — would “expand” and, like a living being at midday, would “repel” the sun in the opposite direction, inevitably tilting toward Earth.

The Santiago de Cuba magazine El Pensil sounded the alarm on May 15:

“The problem of the encounter becomes ‘complicated.’ At what exact moment will our globe find itself behind the star in relation to the sun? This critical date will occur on May 18…and if the tail reaches a little over 23 million kilometers (the distance between the comet’s nucleus and us that day), the entire globe will find itself submerged during the afternoon in the heart of the comet’s tail.” So, even evading the nucleus did not mean escaping what El Pensil called “a terrible eventuality.”

In the run-up to the event, the state of paranoia had intensified to such an extent that, in the shadow of the comet, a thousand and one events occurred: suicide attempts, thefts, looting, pilgrimages to the Sanctuary of El Cobre, kidnappings of young girls, hasty marriages. There was no shortage of generous souls who donated their belongings to the Church, or criminals who turned themselves in at the nearest police station, in both cases to make it to the Final Judgment “in good standing.” But it didn’t stop there.

At 3:30 p.m. on the 18th, an unprecedented roar was heard that shook the city of Pinar del Río from one end to the other. The infernal echo hadn’t even died away and already thousands of Pinar del Río residents were running into the streets in a panic, trying to escape an invisible enemy. “The comet…it was the tail of the comet…! The world is ending!” they shouted. In reality, the chain explosion of several crates of dynamite had started at the Ravena Rural Guard barracks from its foundations, leaving hundreds dead and wounded. Even though the event was not influenced by the galaxy, it was an absolute catastrophe.

Having lost patience with the panorama of excessive speculation, and armed with confidence after verifying the message received from above, Jesuit Father Mariano Gutiérrez-Lanza, deputy director of the Belén Observatory, waylaid by organizing a scientific gathering to explain the results of his investigations. He denounced the avalanche of “tragic-effectual” writings disseminated by the press, contrary to what was clarified by the most serious astronomers, that had generated the lamentable and dangerous hysteria among the Cuban population. Instead, he called for “discarding all childish alarm” and admiring such a “spectacular and harmless” phenomenon.

For its part, the popular newspaper El Cubano Libre asserted in bold headlines: “No catastrophe will occur today,” “Life on Earth is guaranteed,” while in its “Notas and Noticias” section it noted:

“This article would be endless if we reflected in it everything the masses felt and thought yesterday, until midnight, on the occasion of the conjunction of Halley’s Comet with our poor Earth. More than a little more trembling than the comet, all the people who were scared to death last night will have woken up today…. When the nine o’clock bell rang, nature smiled more peacefully than ever. Not a single meteor, not the fleeting trail of a wandering star, not a single subtle dusting; nothing at all.”

And it’s trailing!

Many years later, journalist Waldemar León would leave his testimony in the magazine Bohemia on February 10, 1967:

“In 1910, I was five years old and my relatives, foreseeing the impossibility of seeing it again in 1986, woke me up in the early hours of May 17. Thus, I was able to contemplate it, when the distance separating it from Earth was relatively short, in all its splendor with its luminous tail, formed by bursts of brilliant, discontinuous light, more intense in some sections than in others. It was an unforgettable fantasy spectacle.”

The one who really knew how to turn Halley’s Comet into a show was the actor and master of humor Carlos Luis de la Tejera. How can we forget his hilarious monologue in which the CEO of a company sends a memo to a factory manager and, as the message passes through the various “levels,” it reaches “the bottom” more nebulous than a comet itself:

“The CEO is turning 76 on Friday, so everyone is free to attend the party in the dining room, with the Halley group and their comets. Everyone must go ‘naked’ and wear safety helmets, because it will rain and there will be a tremendous party in the factory yard.”

To laugh a bit and reflect on the noises of our communication.

Like one condemned to eternal pilgrimage, Halley’s Comet has already begun its cosmic journey back to Earth, after reaching aphelion, the point farthest from the sun. It is estimated that, before reaching our planet, it will cross the orbits of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and Jupiter.

Experts predict that Halley’s comet will be visible up to ten times brighter than the last time, in 1986. So we have to wait until — just in case, mark the date — June 28, 2061. This is definitely going to be a long time.