Red and blue, white and stars, two flags form a canopy in the Caribbean skies: those of Cuba and Puerto Rico wave as if they were “two wings of a bird.” This poetic truth, expressed by the patriot Lola Rodríguez de Tió, evokes an air of freedom; a legend forged in struggle, shared longings and the certainty of two islands that, despite the miles and political contexts that separate them, have had closely intertwined destinies.

The history that unites and distinguishes both banners — from their earliest days to their final assumptions — is as beautiful and eventful as a weather vane at the mercy of the winds.

Although it dates back much longer, the origin of the Cuban flag has been better clarified and documented. According to a story written in 1873 by Cirilo Villaverde, celebrated author of the novel Cecilia Valdés and personal secretary to General Narciso López, the latter, allied with the Cuban patriots exiled in New York in the mid-19th century, had an epiphany while looking out his bedroom window one morning: “In the distance, he could see in the sky a triangle of red clouds heralding dawn, and in its center shone the morning star of Venus, while two white clouds extended from the triangle to divide the resplendent sky into three blue stripes.”

At a meeting of conspirators, López presented his “enlightened” proposal for the flag, whose tricolor scheme bore, incidentally, a resemblance to the flags of the United States and France. It was suggested that he place “the Eye of Providence” in the center of the triangle, but the Venezuelan soldier preferred “the star of the original flag of Texas.” Underlying this choice lay the desire for the island to become a U.S. territory. Miguel Teurbe Tolón drafted the idea, and his wife and cousin Emilia Tolón embroidered it with exquisite hands.

The three blue stripes represented each of the provinces into which Cuba was divided; the white stripes represented the purity of ideals; the equilateral triangle was a Masonic motif of the Holy Trinity, and its red color alluded to blood and patriotic fervor. In May 1850, Narciso López ventured to land on Cuban soil and plant in Cárdenas the flag that would later become the national symbol (although Céspedes’s flag later emerged, today practically confined to the symbolic space of Parliament).

Clearly inspired by the Cuban flag, the Puerto Rican flag, known as “the one-star flag,” bears the same colors, except in inverted positions and with different meanings: the star represents the Commonwealth; the sides of the triangle surrounding it symbolize the integrity of the republican form of government represented by three balanced government branches: legislative, executive and judicial. The blue recalls the sky and the sea. The red stripes are associated with the blood shed by warriors, while the two white stripes reflect victory and peace.

Until its appearance, Puerto Ricans used the flag of Lares (very similar to that of the Dominican Republic, with a star in the upper left corner). Its creator and Founding Father of the Nation, Ramón Emeterio Betances — who proclaimed the republic the same year that the Cry of Yara occurred in Cuba — approved its adoption as the small island’s new representative flag.

The two flags are so similar and their shared history is so neglected that there has been no shortage of unfortunate confusion between the two. In the spring of 2016, the diplomatic thaw between Cuba and the United States not only brought President Obama to a Fast & Furious 8 film set and Carnival cruises. The amazing Spiderman also didn’t want to miss the party, leaping across the rooftops of the Villa Clara town of Remedios. However, an almost imperceptible slip by the illustrator in charge of that comic left the Marvel superhero entangled in a spider’s web, as a flag that was supposed to be Cuban, but whose colors were inverted, can be seen waving in the background of the comic.

Why are the flags of Cuba and Puerto Rico so similar? What makes them so close and, at the same time, so different? Who was behind their creation? Why is it linked to Martí and the Cuban independence cause? We find the answers in history.

The Borinquen Club

“And what shall I give to the two beloved lands, but the fire of my heart.” José Martí’s Antillean vision was a constant in his party. Suffice it to say that, as the first and essential article of his party’s foundations, he declared: “The Cuban Revolutionary Party is established to achieve, with the united efforts of all men of good will, the absolute independence of Cuba and to promote and assist that of Puerto Rico.”

Following that logic and with deep commitment, he strengthened his collaboration with Betances and Hostos, while his fiery eloquence strengthened camaraderie with the Puerto Rican diaspora in the United States. To unite efforts in the face of the impending war, Martí’s preaching motivated the organization of clubs, and thus, on February 28, 1892, the Borinquen Club was founded in New York. It provided not only significant financial support for Cuba’s emancipation struggle, but also weapons and soldiers.

The founding rally — held at 57 25W Street — was well attended. It is said that nearly 200 Puerto Ricans attended, including many Puerto Rican and Cuban women, and that Martí was also present. Its founding leaders were Sotero Figueroa, appointed president; Antonio Vélez Alvarado, vice president; Modesto A. Tirado, treasurer; Francisco Gonzalo (Pachín) Marín was the minutes secretary; while Cuban Gonzalo de Quesada was among the members.

As the Puerto Rican exile community grew, the Borinquen Club continued to strengthen. They appointed Ramón Emeterio Betances, based in Paris, as general delegate and designated representatives in several countries, including Eugenio María de Hostos in Chile. A few months later, the group formally affiliated with the party founded by Martí.

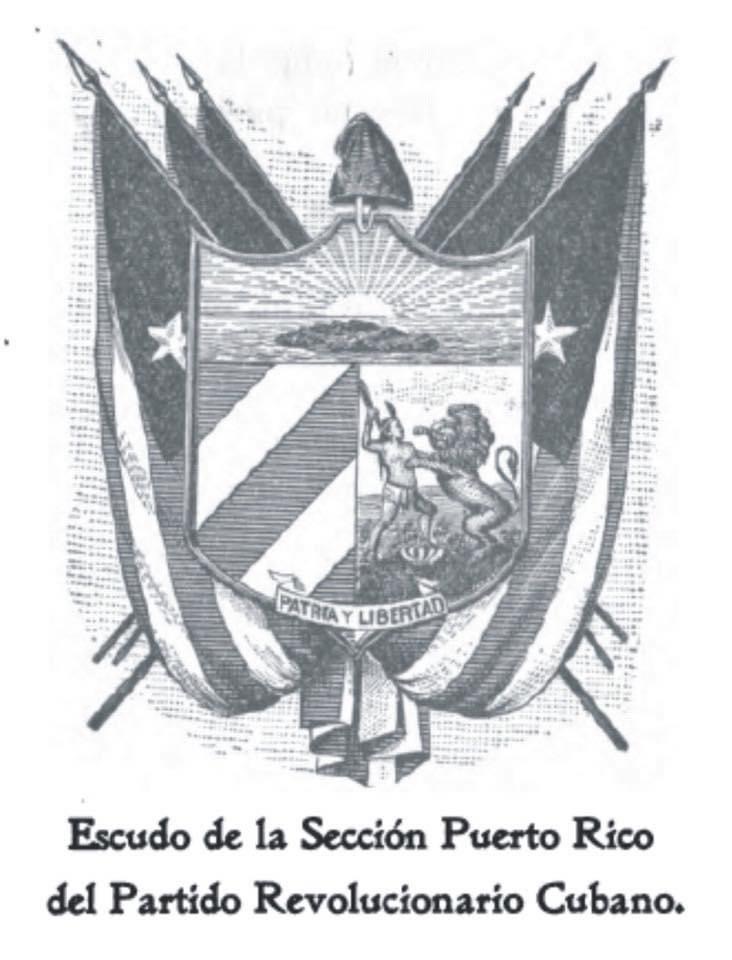

A resurrection of the former Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico, the Borinquen Club was the most important Puerto Rican political organization at the time. Under its auspices, the new national flag was born and it sheltered hundreds of men and women who would continue the fight for Puerto Rico’s right to independence at the beginning of the 20th century, which led to the creation of the Nationalist Party in 1922.

A matter of patriotic importance

Under Betances’ influence — Martí had already died — the Puerto Rican exiles decided to establish their own coordinating structure to channel their homeland’s independence, even though they remained subordinate to the Cuban Revolutionary Party. For this reason, it was agreed to convene a General Assembly in December 1895.

On Saturday the 21st, the following announcement appeared in the newspaper Patria: “To all Puerto Ricans: Tomorrow, Sunday, at two-thirty in the afternoon, Puerto Ricans will meet in the main hall of number 57, west of Fifth Street, at the corner of Sixth Avenue, to discuss matters of patriotic importance. All Puerto Ricans who love Antillean independence are hereby invited.”

At that momentous meeting, held in Chimney Corner Hall, 59 Puerto Ricans agreed to transform the Borinquen Club into the Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party. The approval of the new flag was part of the agenda: “[Juan de Matta] Terreforte, one of the survivors of the Cry of Lares, presented the new flag, which is the same shape as the Cuban flag, with the difference that the colors have been reversed: white stripes and a blue triangle instead of a red one, with the same lone white star in the center.” Those gathered that day elected Ponce physician Julio Henna as president of the Section and ratified the leadership of Betances, with whom they consulted about the flag prototype.

It is worth clarifying that, in this case, the terms “conception” and “adoption” were not simultaneous events. Although December 22, 1895, would go down in Puerto Rican history as Flag Day, as it was the first “public” — let’s say — time that the new tricolor flag was raised as a symbol of the nation, the flag had already been born three years earlier.

At Micaela’s house

What apparently wasn’t made clear at that historic gathering was the name of the flag’s designer. Otherwise, the debate that dragged on for years, like a heavy tail, would not have arisen. Three names have been indiscriminately cited as the “true” authors, amid controversy and certainty.

Roberto H. Todd, one of the founders of the Puerto Rico Section, attributed the authorship to Manuel Besosa, also a member of that board. Todd maintained in his version that María Manuela (Mima) Besosa told him that her father had asked her to sew a Puerto Rican flag. However, Mima Besosa never said that her father created it, only that she sewed it. For his part, Terreforte attributed the invention to the poet and combatant Pachín Marín, who, while in Jamaica, “wandering and about to leave for New York,” had written to him suggesting the idea of inverting the colors of the Cuban flag.

The documentary evidence captured in the book La Historia de la Bandera de Puerto Rico. Del conflicto a la certeza, following recent research by historian Joseph Harrison, dispels any doubt and centers the authorship of the Puerto Rican flag on the figure of Antonio Vélez Alvarado.

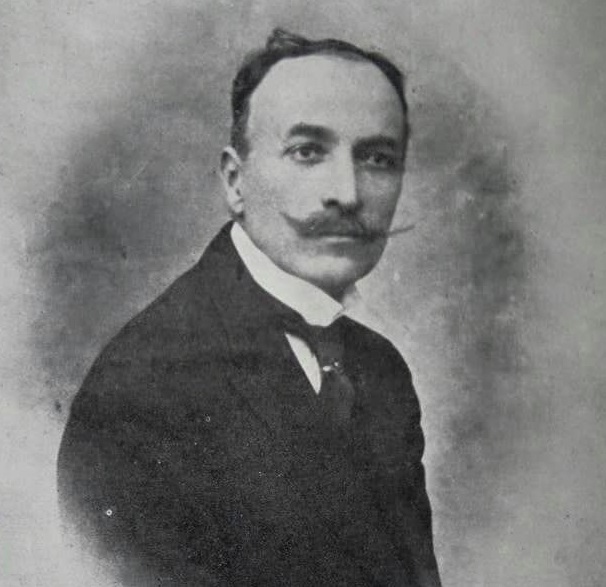

Born on June 12, 1864, in Manatí, Puerto Rico, Antonio began writing articles with progressive ideas at a young age — under the pseudonym Yuri. He was a typographer and correspondent for several newspapers and founded his own, El Rebenque and El Espectador Matinal. At 17, his father sent him to New York, where he founded the Revista Popular and the Gaceta del Pueblo. A sympathizer of the Cuban libertarian movement, he joined the Borinquen Club and befriended the Cuban Apostle Martí. In fact, he made his printing press — located on the seventh floor of The New York World building — available to him to publish the first issues of Patria.

As he advanced in years, in an interview with the local newspaper El Mundo (May 18, 1941), Vélez Alvarado testified that on June 11, 1892, around three in the afternoon, while working in his Manhattan office, he felt the need to rest his eyes and spent a minute gazing, absorbed, at a small Cuban flag hanging on the wall. When he looked away, he noticed that, as if suffering from a strange instant color blindness, the colors were suddenly inverted: red seemed blue to him, and blue seemed red. Right then and there, he thought: “If Cubans and Puerto Ricans are going to fight together as brothers, nothing could be more just than the flags also being sisters.”

Possessed by the optical illusion that had taken hold in his pupils, the young man ran to his fellow countryman Domingo Peraza’s pharmacy to buy papers in all three colors. Back at the office, he cut out and outlined what would become the pioneering model of his “twin” Cuban flag, with the slight color inversion. He then took the design to his neighbor, Mrs. Micaela Dalmau, a Puerto Rican whom Martí frequented to hear her play La Borinqueña on the piano. The woman embraced the idea with equal enthusiasm and went out to buy silk to make the flag. When it was ready, they invited Martí and other friends — including Pachín Marín — to a gathering at Micaela’s house to present their creation.

The brand-new flag was acclaimed by those present and enjoyed the approval of Martí, who published on July 2, 1892, in the social section “En Casa” of the newspaper Patria: “Yesterday, a few days ago, Don Antonio Vélez Alvarado fed us under the two flags. We lived for a few hours, which is saying a lot in these exiles. What heartfelt songs, those of Francisco Marín…! What a union in those affections of the Cuban décima and the Puerto Rican Christmas carol! And to bid us farewell, the seventy-year-old woman, dressed in white and with white hair, sat at the piano to play for us the country’s anthem.”