Looking at the photos of Villalón Park in Vedado, I was reminded of the many times I passed by there during my university years. On one corner, the Amadeo Roldán Theater; on the other, Máximo Gómez’s house.

Every time I’ve returned to Havana, I go back to that place in search of my own ghosts. I wander around the park, drawn by the figure of José Ramón Villalón, longing to see him. I explore its columns, scraping for fragments of his memory to transform him into a literary character. One day I even rang the doorbell of the house where I found out he had lived, across from the park.

What could Eusebio Leal say about those ruins? I once asked him about Villalón and, to my surprise, learned they were relatives. Now only souls wander among the rubble: ladies and gentlemen of yesterday who watch, entranced, the destruction.

A child crosses what must once have been grass; a woman returning from her bread run has already forgotten that the park is named Gonzalo de Quesada y Aróstegui, the patriot friend of Villalón, as a descendant wrote in documents easily found on the internet, among them the one titled El libro de los Wilson.

There’s no forgiveness for memory, and it clings to melancholy. I imagine that for those who grew up around Villalón Park, for those who hold memories linked to every bench or every plant, the destruction, the dumpster, the oblivion must be painful.

Neglect gives way to forgetfulness, and this eats away at the material like saltpeter. The ruin could one day turn to dust, and you can be sure that this dust will end up buried by a modern building, perhaps designed for tourists who may never arrive, or for millionaires already being forged in the shadow of bureaucracy, ideology and the ghosts of history.

But what about José Ramón Villalón? It was a surprise to learn that he was the creator of an artillery piece used during the War of Independence. Perhaps Juan Padrón modeled his character Oliverio, the inventor in the comic strip Elpidio Valdés, on him.

Oliverio surely embodies the many inventors who participated in our independence struggles, among them the engineer José Ramón Villalón. As I immersed myself in his story, connecting the dots and evoking personalities and moments, the real events began to blend, liquefying in my imagination. Thus, I also share with you fragments of what I composed about the life of this man: patriot, founder, lifeblood of our national blood.

An episode: Villalón’s pneumatic cannon

Villalón’s pneumatic cannon was of the Sims-Dudley type. He had made some adaptations, adding three tubes: two allowing the evacuation of compressed gases and one for the expulsion of the projectile. In addition to dynamite, he used nitroglycerin. His creation kept him busy for months in an apartment overlooking a gloomy but cool street entrance, and for testing, he went to Long Island Sound with his assistants, because he was in New York. They activated the cannon along the Hudson River and fired the first shot, but the cannon would prove its effectiveness the next day in the island’s plains, so Villalón had to head to Florida to embark for that test, bound for the Cuban coast.

In addition to the cannon, the steamer Three Friends had a thousand weapons on board: modern rifles, shotguns, Mauser and Winchester rifles, 500,000 rounds and 2,000 pounds of dynamite. The expedition had two commanders: one at sea, General Castillo Duany, and the other on land, Puerto Rican General Juan Rius Rivera, a veteran of the Great War, where he had fought under Calixto García, to whom, incidentally, José Ramón had sent one of his aides with a good team of artillerymen. That man was named Frederick Funston, but that’s another story.

We’re on the high seas, and the expedition members had been divided into four groups. José Ramón, with the rank of captain, commanded eight men: the four assistants who had accompanied him from New York and four soldiers who would be in charge of the mules on which he was to transport the cargo. He wore a straw hat and a cotton shirt. He remained silent and thoughtful most of the time, but at dawn, the Cuban essence of his character escaped through the intricacies of his formality.

Sometimes he met on deck with a young man named Francisco, whose conversations made him appear older than his age. He was the fourth son of Máximo Gómez and had accompanied José Martí on his voyages to Key West, Tampa, New Orleans, Costa Rica, Panama, Jamaica and the Dominican Republic. José Ramón took a great liking to him.

Five days after setting sail from the left bank of the Saint Johns River in Jacksonville, the expedition members discovered the beam of a streetlight in the distance. It was coming from a camp at Cape Corrientes, and they headed in that direction, so the boats carried the group of patriots to a cove on a beach called María la Gorda, where the landing took place.

Their stay on that coast lasted more than a week. The objective was to reach Antonio Maceo’s troops. The path was tortuous; the dog tooth rocks tore through boots and tried to open the belly of one of the mules; then there was the swamp: the sea grape and guano concentrated the glare of the sun. The legendary general was eager to see the effectiveness of the reinforcements and welcomed them with joy.

One day, not too far from that day, the explorers discovered a fort occupied by a Spanish column and organized the action. Maceo was eager to test José Ramón’s cannon. Jose Ramón urged the gunners on. The maneuver made excellent impressions, but the weapon’s true power, augmented by the nitroglycerin bags, had yet to be tested. The roar of the weapon terrified the opposing ranks. A great battle was approaching: Ceja del Negro.

The troops received a cruel onslaught in the rain. Not only did they lose their standard-bearer, but the fire became fierce and men began to fall on the battlefield. José Ramón himself ended up missing half his men. The enemy squadrons managed to ambush the Cubans, who were accompanied by a large number of civilians who, confused by the maneuver, abandoned the river where the enemy was hiding, and children, women and the elderly fell victim to crossfire.

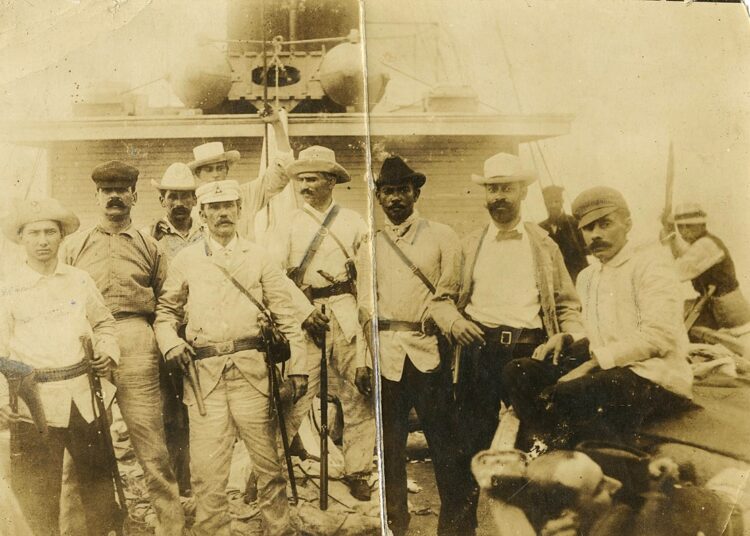

Standing, left: José Ramón Villalón, in the United States, 1898. Also, Calixto García, José Miguel Gómez, José A. González Lanuza and Manuel Sanguily. Photo: Author’s archive.

General Pedro Vargas urgently called José Ramón. “We must do something with that artillery,” he shouted. He pointed to a rise where the enemy seemed impregnable, but the artillerymen had to arrive, and they did. The shots from the pneumatic cannon made the ground shake; it wasn’t enough to force Weyler’s troops to retreat. The power of the attack provoked confusion. Terror. Maceo ordered a machete charge. The rain had stopped. Blood was running through the stream. The smoke from the gunpowder mixed with the mist, diluting the bloody scene.

José Ramón received orders to increase his artillery firepower; he must take advantage of the time and produce ammunition. Maceo sensed a new offensive, and time was running out. The days are turning dizzying for him, who has been promoted to commander and must leave with the Lieutenant and his artillery team. The famous pneumatic cannon has the town of Artemisa, his other major action, in check. Once again the dynamite; the fire causes panic; once again, the Mambí fighters surprise with their bombardment.

Maceo receives orders and crosses the Mariel to Majana path in a boat with a small group of collaborators. It was December 1896 when a bullet hit his body that had so often been riddled with shrapnel. The Mambí leader fell in San Pedro before the eyes of a detachment, and when Francisco, the young man with whom José Ramón had spoken so often, found out, he ran to the body. The opposing troops are lurking and that’s when the boy takes a piece of paper out of his pocket on which he writes: “Goodbye, my loved ones, I will love you as much in another life as in this one, your Panchito Gómez Toro, friend or enemy, please send this note from a dead person.”

José Ramón feels something collapsing in his soul. He is consumed by grief and the feeling that the war is brutal and unjust prevails. The Republic itself seems broken, strained by intrigues that alienate generals and entangle hearts like a thorny creeper advancing through the darkness, only to one day reveal the flash of an explosion: the Maine bursts like a firecracker in Havana Bay.

And since José Ramón had been elected to the Assembly, he was appointed as one of the five members of the commission that would negotiate the disbandment of the Liberation Army in Washington, its recognition. He was thirty-four years old when he returned to New York, and was engaged in efforts that seemed to be bearing fruit with his four companions, when fate struck again: Calixto García, the most veteran of the independence leaders, the central figure of the group to which he belonged, died, leaving the commission devastated and causing José Ramón to reproach himself, once again, for the fate of his compatriots and his own.

“What’s the point of a revolution?” he sometimes asked himself. “What was the point of the war?” As secretary of the group, he had too many responsibilities and couldn’t get lost in disquisitions. Life waits for nothing, and those still fortunate enough to have it must hurry up to live up to it.

***

José Ramón Villalón Sánchez was born on September 8, 1864, in Santiago de Cuba. He lived in Barcelona and Colombia, where he worked on the railroads. He studied at Lehigh University in the United States and trained as a civil engineer. He was a professor of calculus at the University of Havana and Secretary of Public Works during the first U.S. interventionist government, a position he held again during Mario García Menocal’s first administration. He died in 1938.

Hola Leandro Estupiñan –

Me llamo José Ramón Villalon y Capmany. A los 69 años de edad, mi visabuelo fue el protagonista de tu último artículo On Cuba News de Sep 2025. Felicitaciones, lo compartiré con mi familia extendía.

Me encantaría correspondíar contigo. Reconozco que ese verbo no existe en este lenguaje pero quizás debería.

Resido en Miami después de vivir la mayoría de mi vida adulta en Ecuador, México, Islas Virgenes y Ámsterdam como biólogo marino.

Por Favor comunícate conmigo si te antoja a mi correo electrónico.

Saludos,

-jose