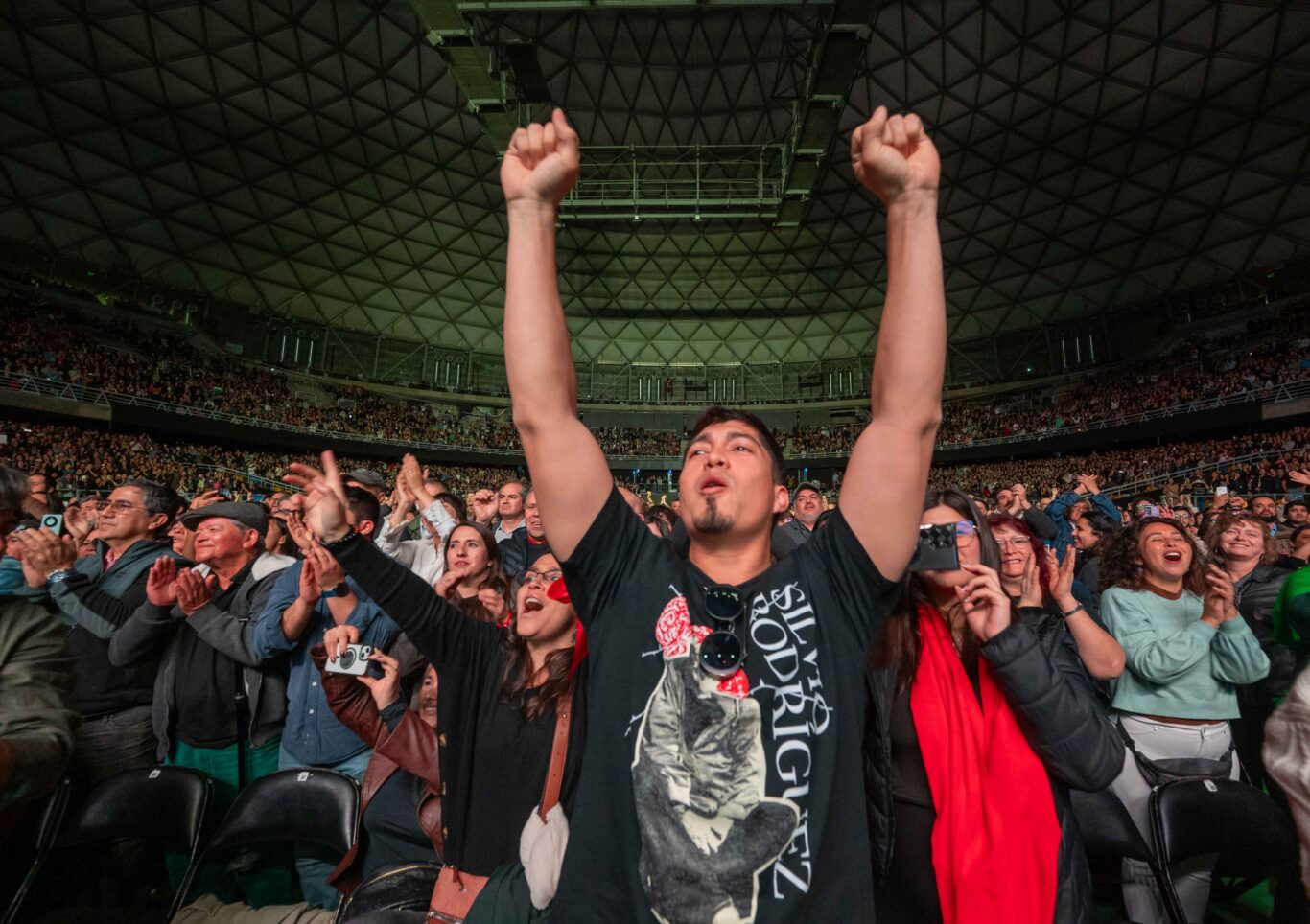

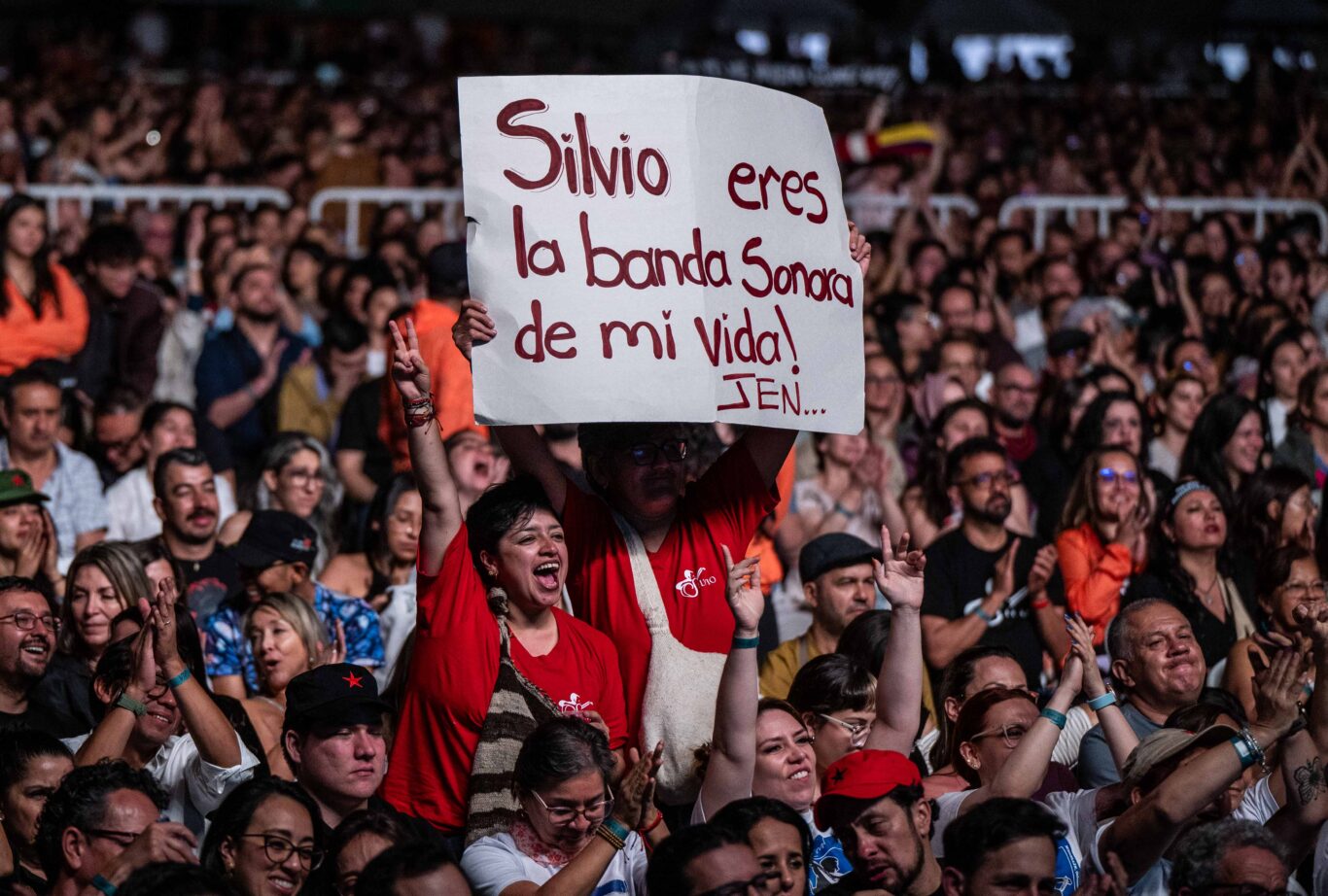

I spend a good part of the time, at the concerts on this Latin American tour with Silvio, scrutinizing the audience through the viewfinder: the fixed gazes, the shining eyes, the lips that move before he does, the hands that rise as if marking an intimate rhythm. It moves me to see how a handful of verses and a progression of chords activate memories, grief, joy and life-changing decisions. In that sea of thousands, personal stories multiply, interwoven with songs born in the intimacy of a man that, as they took flight, became collective feelings.

The tour — that has gone from Havana, Santiago, Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Lima, and will continue in Medellín and Cali — has traced, more than an itinerary, a map of memory.

Reinaldo Pineda, a 57-year-old Costa Rican, has already covered several kilometers of this route: “I was in Havana, at the first one in Chile, the first two in Buenos Aires, the two in Montevideo and in Lima. And I’ll be in Medellín and Cali to close it out.” In each city, he says, he felt variations of the same heartbeat: “I’ve experienced it with different intensity, because of the people I shared it with. In all of them, the emotion was raw.”

There are constants that run through his experience: “Perhaps the tributes to his contemporaries (Vicente, Noel and Pablo), experienced differently in each place.” And there are moments that break him: “Starting with ‘Ala de colibrí,’ because of the emotion I felt with my companions.… Everywhere, the wait for ‘Aprendiz’’ was long.” He says he is united by a shared certainty: “Feeling Cuba and Silvio very close to my heart, in complicated times on the island.”

From Peru, Jhonatan — a teacher — found a circle to close on this journey: “I’ve been listening to Silvio since I was fifteen. His poetry set to song has been, is and will be my refuge. My daughter’s name is Adriana Mariana: her middle name is for ‘Y Mariana.’ While she was being born, ‘Sólo el amor’ was playing in the delivery room.”

He traveled to Havana and Lima: “I wanted to see him in his homeland and in mine. In Havana, I felt like I was witnessing history; in Lima, that I was living a piece of my own.” “Venga la esperanza” was its guiding thread: “In Havana, it seemed as if the audience was breathing as one, a song that encapsulated dignity and faith. In Lima, it was more of a prayer not to lose the light.” The high point came with “Yolanda,” sung by Silvio and Malva: “It was closing a cycle between Pablo’s absence and Silvio’s continued presence. Art doesn’t die; it transforms, it’s inherited, it outlives us.”

That memory — of people, cities and struggles — is also mentioned by Aida Roa Villar, a Chilean woman who turned 50 at one of these concerts. “I grew up with his songs; I learned them from my mother. They’ve been there for me in my most difficult and happiest moments,” she says. On this tour, she was in Santiago, Chile, Buenos Aires and Lima. Each venue evoked a different emotion: “In Chile, seven years of waiting. Total emotion. In Buenos Aires, I was worried about his health; I admire that he gives so many concerts and pours his heart and soul into every performance. In Lima, on my fiftieth birthday, I cried buckets.”

In Argentina, the generation that knew him in classrooms and at marches also left their mark. Clara Calicchio, 34, speaks from the house where, as a child, she transcribed lyrics and asked questions about words: “Silvio taught more than just music. In 2005, I saw him at the march against the FTAA. My devotion grew.”

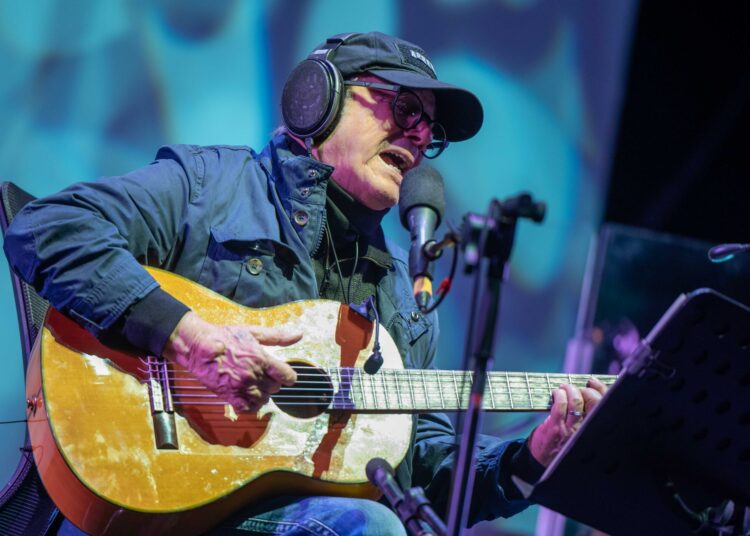

This tour found her at the first Movistar Arena in Chile and at all three in Buenos Aires. “I went to the first one in Argentina with my whole family; there were eight of us.” She is moved by the shared ritual — “when he mentions Che and we applaud, when he says revolution and everyone shouts” — and he focuses on two moments: the “Eva” that in 2018 was sung with green handkerchiefs held high (“more heartfelt in Argentina”) and the Sunday in Buenos Aires, when “Te amaré” became silence: “It was listening to Silvio recite and sing; his desire to give us that song. One of the best memories I take with me.”

Juan Sotelo Navarro, a 60-year-old Chilean, owes his discovery of the singer-songwriter to his wife during their courtship, more than four decades ago. Since then, he says, his work has accompanied him, “even in those years ‘my dog would look for me at his door when I got lost.’” Her emotional response has a title: “I was moved every time I heard ‘La era está pariendo un corazón’. It was one of the first ‘strange’ songs I heard in my youth. I tried to decipher how that infernal guitar could sound like that. I cried every time I heard it.”

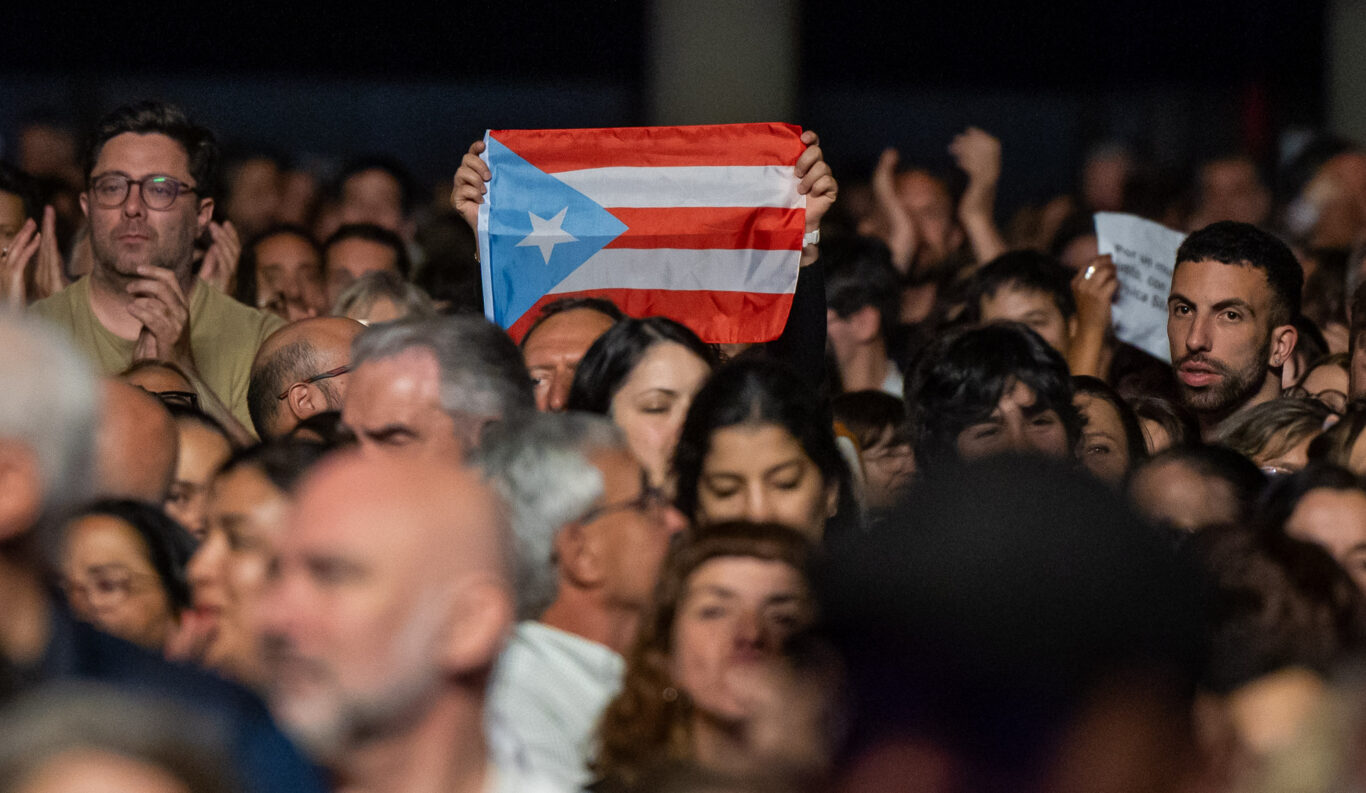

Another perspective, born from both research and affection, came from Puerto Rico. Limarí Rivera Ríos, 42, author of Silvio Rodríguez. Poética del amor revolucionario, traveled to Buenos Aires driven by a constellation of dates: “On October 21st, my husband and I were celebrating twenty years together and the presentation of my book in Argentina was approaching.” At the concert, she confesses, “I broke down, almost cathartically, with ‘Ala de colibrí’.” And she cherishes an image of the silence: “The solemn and perfect reading of the poem ‘Halt!’ encapsulated everyone’s profound respect.”

For Carlos Alberto Maldonado Espinaza, a Chilean almost 53, the first spark came at age 12 with “Debo partirme en dos”: “It was like a blow to the head, and from then on the journey hasn’t stopped.” He followed the tour from Havana, the four concerts in Santiago, Lima, and he already has tickets for Medellín and Cali. He’s surprised by the nuances of the audience: “Some sing along more, others shout more. Everywhere there were people of all ages, and I love seeing so much youth.” There’s one moment that always resonates with him: the reading of the poem “Halt,” by Luis Rogelio Nogueras. “What I felt differently was what has been happening to me with the poem.” What unites the audiences, he believes, is that “they see Silvio as a balm for these atrocious times.”

Even in Buenos Aires, when his voice gave out one night, the scene was telling. Pilar Faccio, from Argentina, remembers it as a tacit pact: “When it seemed he couldn’t give any more, he sang ‘Ojalá’. During each pause, there was a heavy silence, as if everyone were holding their breath. When the audience started singing along, the verses sounded as if from a single body.”

“Eva” resonates deeply with Pilar, different each time depending on who she sings it with — her mother, a friend, a stranger: “The struggle isn’t the same for everyone, but there’s a voice that speaks to us all.” For her, being at a Silvio Rodríguez concert “is belonging to something bigger than yourself.”

The intimate epic of this tour is also expressed in trips that overflow the schedule. Angie Beatriz Morales Jorquera, from Chile, traces its origins to a university cassette tape, during the dictatorship: “My second mother made me listen to ‘Imagínate’. Since then, not a single day has gone by without his music.” Each concert, she says, stirs her emotions: “Even though we know the lineup, each performance has its own magic. All my emotions just flow, often to the point of tears.” In Lima, she experienced a powerful outpouring: “It was an outpouring of friendship, hugs and tears because so many of my dearest friends were there together.”

Colombia perhaps provided the most vivid adventure on the emotional map. Sergio Giovanny Flórez and María Alejandra Palacio, both 32, decided to turn their fear of not getting tickets into a continental journey: Havana, Santiago, Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Lima.

“Let’s secure the tickets, even if it’s in some random country,” they told each other. They ended up putting together a budget trip, selling scarves in each city to finance lodging and meals. The music, they say, narrated the present of each place: Palestine, Pepe Mujica, Chilean history, the problems of each country. “The same songs have a different social and emotional charge in each square,” Sergio explains.

Their personal anthems were “Te amaré”, which played at their wedding, and “El necio”: “That’s where our scarf ‘Yo me muero como viví’ comes from. That dignity to take on challenges without hurting anyone.” Three scenes sealed the journey: a scarf given to Silvio in Havana; another autographed and returned in Uruguay; and, in Lima, the van stopped by Silvio, Malva and Niurka to thank them: “You’ve seen us at every concert,” they told them. “That the artist recognizes the effort shows Silvio’s humanity and passion,” says María.

At this point, the inventory of songs — “La era está pariendo un corazón”, “Ala de colibrí”, “El necio”, “Te amaré”, “Eva”, “Te recuerdo Amanda”, “Santiago de Chile”, “Yolanda,” “Ojalá”, “Escaramujo”, “Venga la esperanza” — tells as much as the map. They are titles, yes, but above all they are keys that each person uses to open their own door. So is “Halt!”, a poem read by Silvio with a pause that the audience respects as if it were a prayer. And there are the tributes to Pablo Milanés, Vicente Feliú, Noel Nicola; names that, though absent, remain present.

What did I learn by looking at the audience as much as, or even more than at the stage? That the tour doesn’t just reunite a singer-songwriter with his people: it reunites people with themselves. That each stop and each country adds a layer — Chilean history, Cuban faith, Argentine memory, Uruguayan gratitude, Peruvian emotion, the Colombian heartbeat — and yet, the common denominator appears naturally and fluidly: respect, hope, community. Also, that concert after concert, networks of affection, so necessary today, are woven.

At the end of each night, when the ovation stretches out and he takes his bow with that mixture of modesty and tenderness, something lingers, vibrating beyond the last chord and verse. Perhaps it’s what each person in the audience expresses in different words: the certainty that his poetry, set to music, has accompanied us as we grew, loved and endured; that it remains essential. In noisy times, beauty — that beauty that summons us without distance — can still unite us.

The tour continues. People will keep arriving with scarves, with inherited cassettes, with daughters named for songs, with the memory of their first listening still fresh even decades later. And I, behind the viewfinder, will once again seek those gazes.