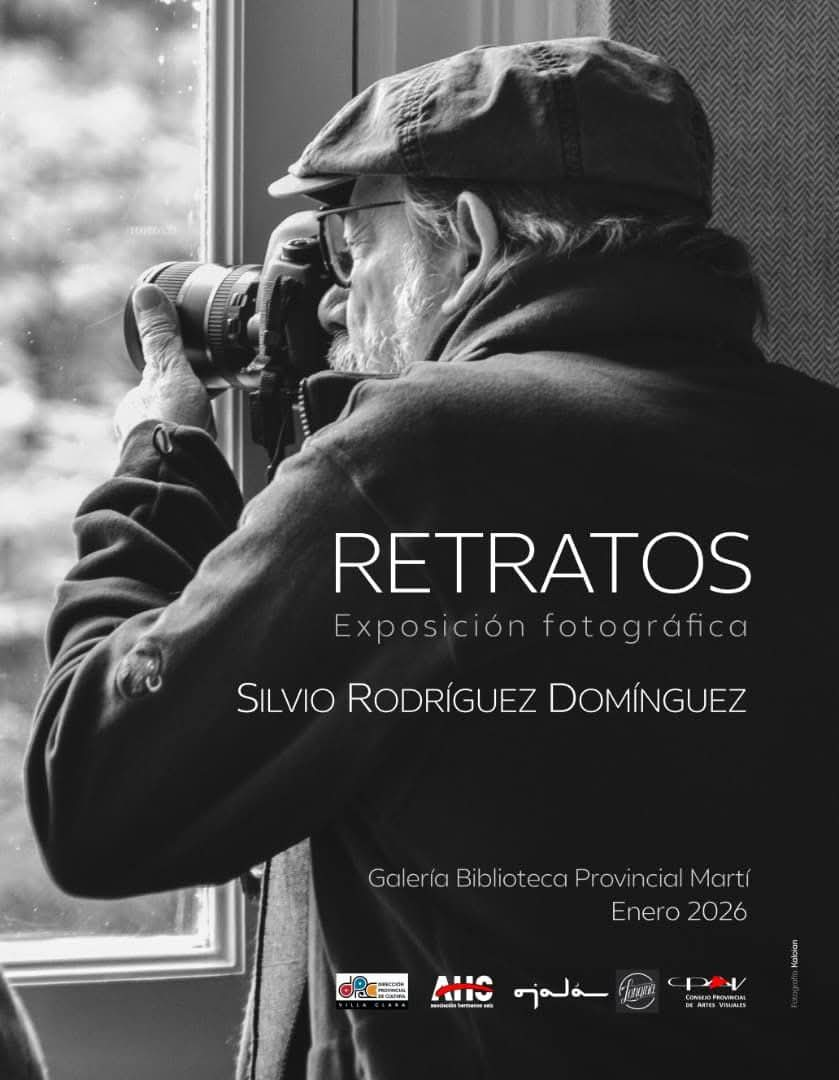

The Longina Trova Festival, held in Santa Clara, dedicated its 30th edition just a couple of weeks ago to Silvio Rodríguez. The tribute unfolded on several levels: a conversation with the singer-songwriter, a special chapter — in concert format — of the television program Entre manos, where he shared the stage and songs with fellow musicians from different generations, and the inauguration of Retratos (Portraits), a photographic exhibition that reveals a less well-known but constant facet of his career: that of Silvio the photographer.

I heard somewhere that photography, for Silvio, was his violon d’ingres, that French expression that refers to a secondary hobby practiced with devotion, beyond a person’s main activity. I understand the reasoning: his profession and his public recognition are undeniably associated with the creation of songs — the songs. However, I disagree. I don’t think that photography is secondary for Silvio. Quite the opposite: I suspect that, throughout his life, a camera has accompanied him even longer than a guitar.

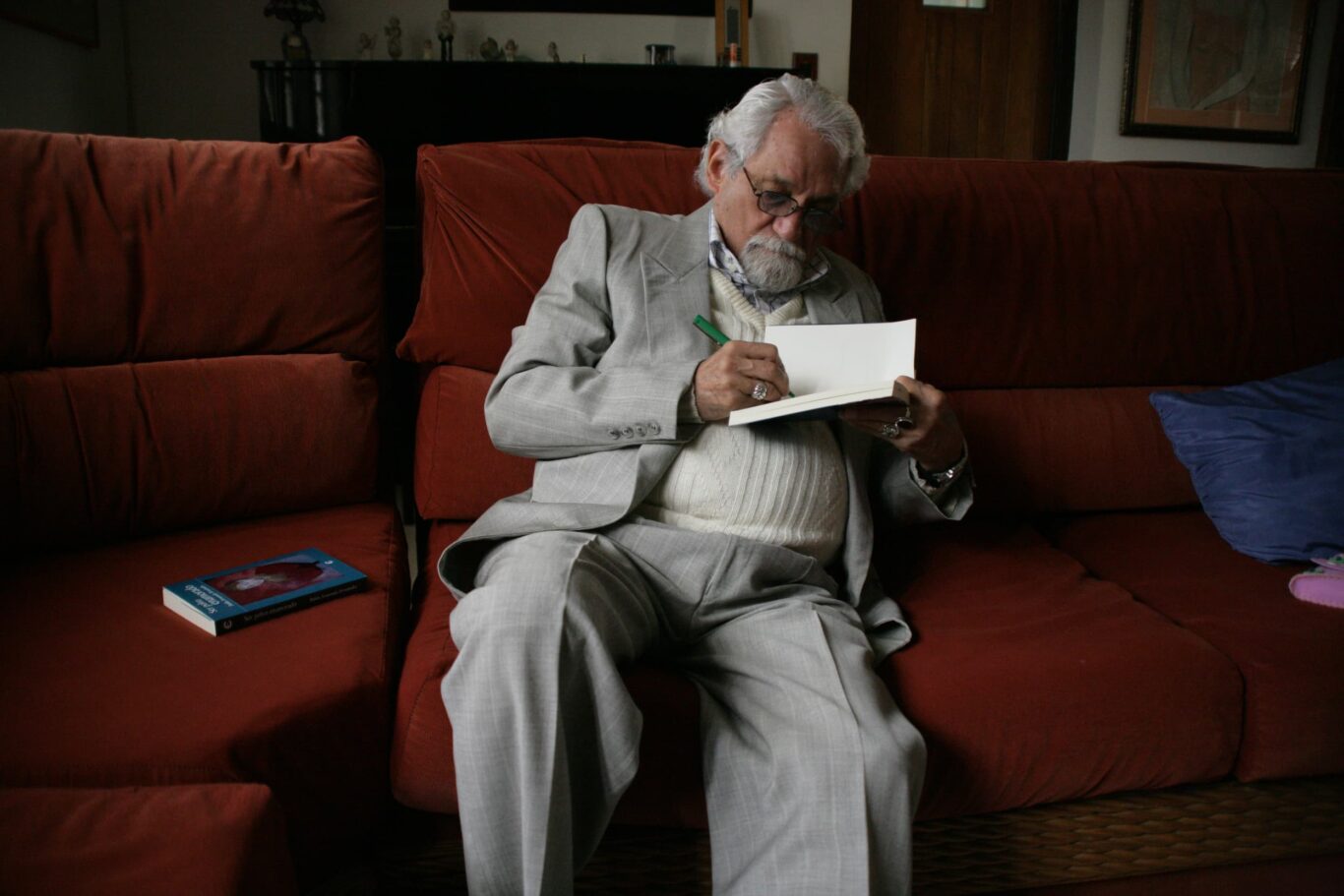

Anyone who has ever crossed paths with him can attest to this. At a concert, at a gathering of friends, as a spectator at any cultural event, walking through his beloved San Antonio de los Baños or driving through Havana in his daily routine — and giving rides to people, as I know he often does — the camera is there. Always. Like a natural extension of his gaze.

I also think about the enormous number of unique images that Silvio has created with verses, and about the camera as another possible tool to draw with light, to bring forth other forms of the visible. In that intersection between word and image there is common ground: the gaze. It is no coincidence that this leads me to think of the Mexican Juan Rulfo, an immense writer and, at the same time, an exceptional photographer. Just looking at his photographs makes you feel like you’re walking through Pedro Páramo: towns frozen in time, dense silences, motionless trains, dust, shadows and light, black and white, faces marked by a history that doesn’t always need words. In Rulfo, as in Silvio, the image doesn’t illustrate the literary work or the song: it dialogues with them from the same sensitive core.

In both cases, what changes is not the intention, but the tool. Sometimes it’s the verse that condenses a scene and makes it unforgettable; other times, it’s the framing that captures an emotion that defies explanation. The camera and the word function as extensions of the same expressive need: to capture what moves, what questions, what leaves a mark. That’s why photography in Silvio’s work cannot be read as an accessory gesture or as a simple record of what surrounds him. It is, rather, another way of thinking about the world, of ordering it, of questioning it.

In essence, it’s about the same thing: having an instrument that allows you to materialize what emanates from sensitivity. It doesn’t matter so much whether the image is born from a guitar, a notebook or a camera. What is decisive is the gaze that articulates them, that unique way of framing reality and giving it meaning. In the end, what remains is not the means, but the image achieved: the one that, like a good song or a great photograph, stays in the memory and continues to speak long after it has been created.

“Do you know why I started with this photography thing?” Silvio asked me recently, and what followed left me pondering. “It was when I was about 17, ever since I learned that UFOs existed. I’ve been carrying a camera ever since, just in case one crosses my path someday, so it doesn’t get away,” he said and smiled. He was holding his camera in his hands at that moment.

And while that unidentified flying object doesn’t appear, the son of Argelia and Dagoberto continues photographing what he finds along the way: places, people, situations. It’s not limited to the act of documenting; it goes beyond that. Like every photographer, he sees more than he looks at. In that frame, in that piece of reality, he imprints a very particular sensibility.

With Retratos, the exhibition that can be visited during January and February at the José Martí Provincial Library gallery in Villa Clara, something happened to me that only happens with photos that don’t go unnoticed: I stopped in front of them. An image captivates you, holds you for a while, forces you to read it, to appropriate it, even to think — with a mixture of admiration, desire and even (healthy?) envy: “I wish I had taken that photo.” And then you remember it. Amidst the flood of images we consume daily, especially in this era of visual overexposure, you may eventually forget the author, but the photograph remains.

My first encounter with some of the images in this exhibition was by chance, a few years ago, while browsing the internet. They appeared on Flickr, that global platform for hosting images and videos launched in 2004, now almost fallen into disuse.

There, Silvio had opened a profile and uploaded some of his photos without telling anyone. The one that impacted me the most then — and still does today — is the portrait of Alberto Tosca and Xiomara Laugart, when the couple, one of the most powerful duos in Cuban music, was beginning their journey in the 1980s.

The photograph, in black and white, taken with 35mm film, spontaneously and without its subjects noticing, doesn’t show them singing. And yet, it reveals the freshness, beauty and impact of that duo, both in music and in life.

As I looked at the rest of the portraits in the exhibition, I understood that what had happened to me with the image of Tosca and Xiomara was neither a coincidence nor a fluke on the photographer’s part. There is a constant: the ability to reveal the essence of the person portrayed.

There is the immense Marta Valdés in profile, also in black and white, with that characteristic gesture of hers; the naive and tender gaze of Haydée Milanés as a child, captured in a technically precise and conceptually luminous chiaroscuro; the images of artists in neighborhoods, on that endless and profoundly human tour.

There is Frank Fernández, the great concert and popular pianist, in a gesture of fierce communion with the piano during that period in the neighborhoods, while the audience listens in astonishment on the rooftops. On those same rooftops where reggaeton plays today, Mozart and Lecuona emerge, interpreted by one of the most important pianists in the world. Or the intimacy of an improvised dressing room in the classroom of a small school in La Timba, when Silvio stealthily slips away to photograph, minutes before going on stage, the cellist Amparo del Riego, the Argentine guitarist Víctor Pellegrini and the flutist Niurka González: the trio absorbed in their music, the scores on improvised music stands, a stream of light that organizes the scene.

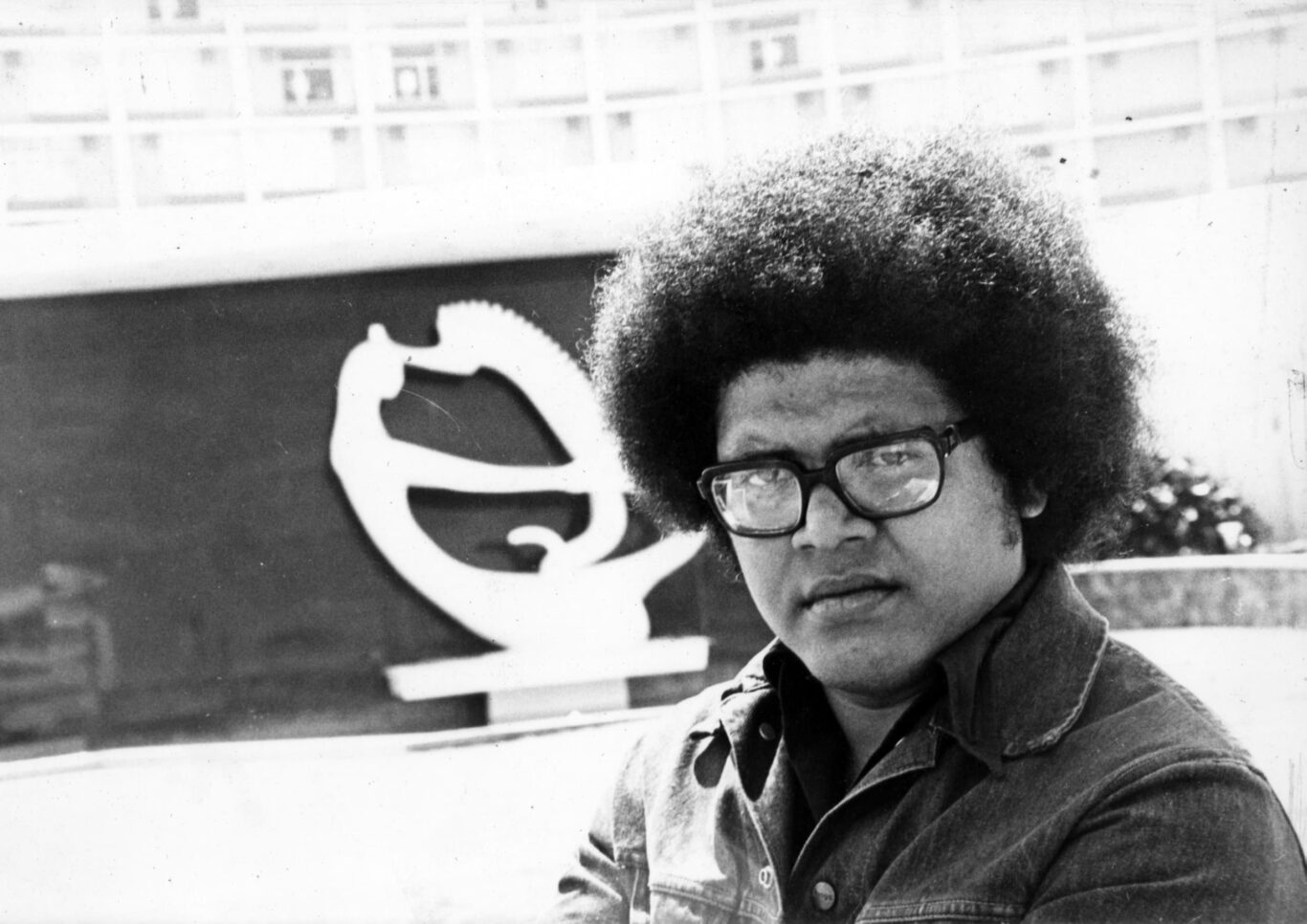

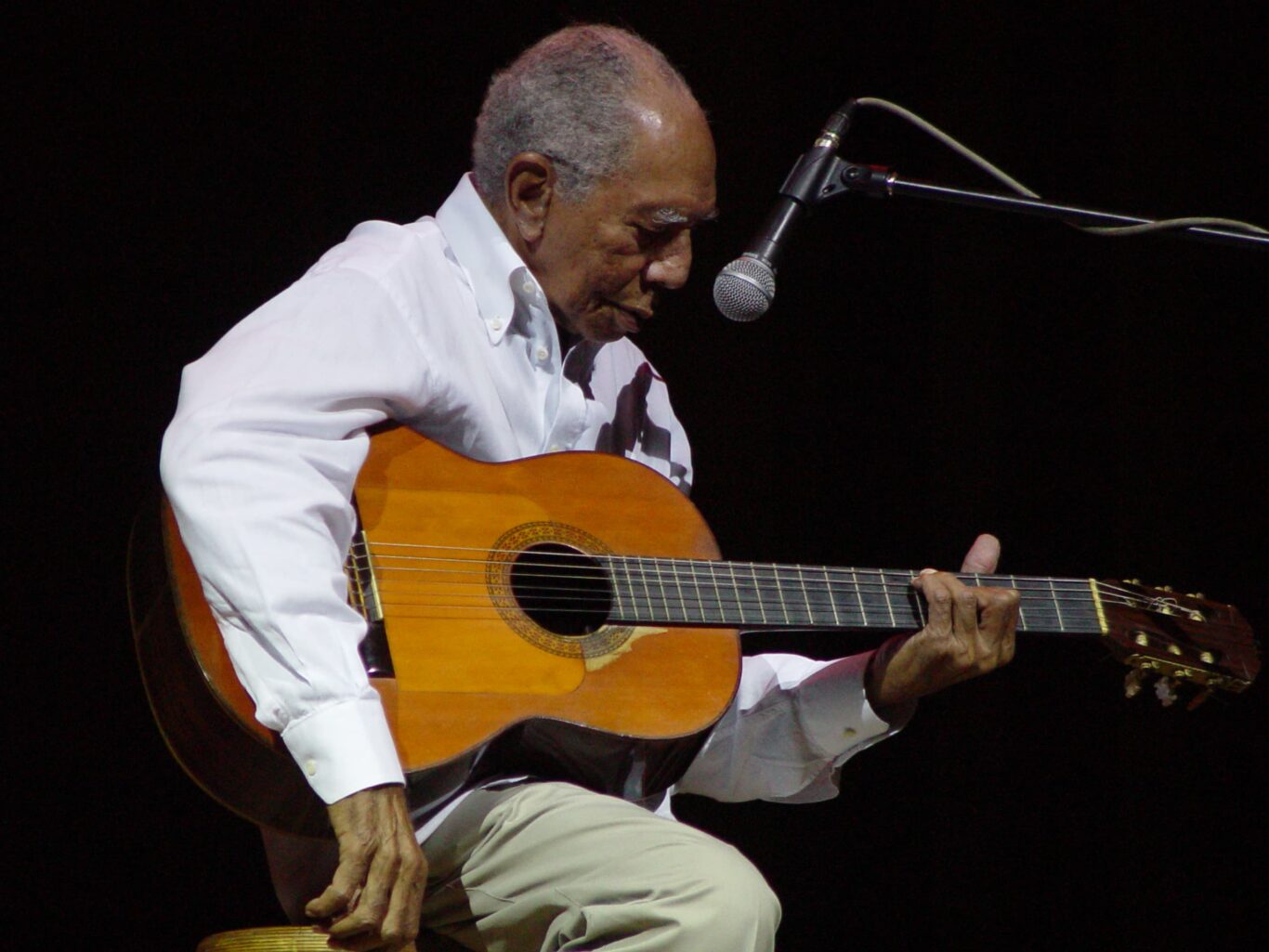

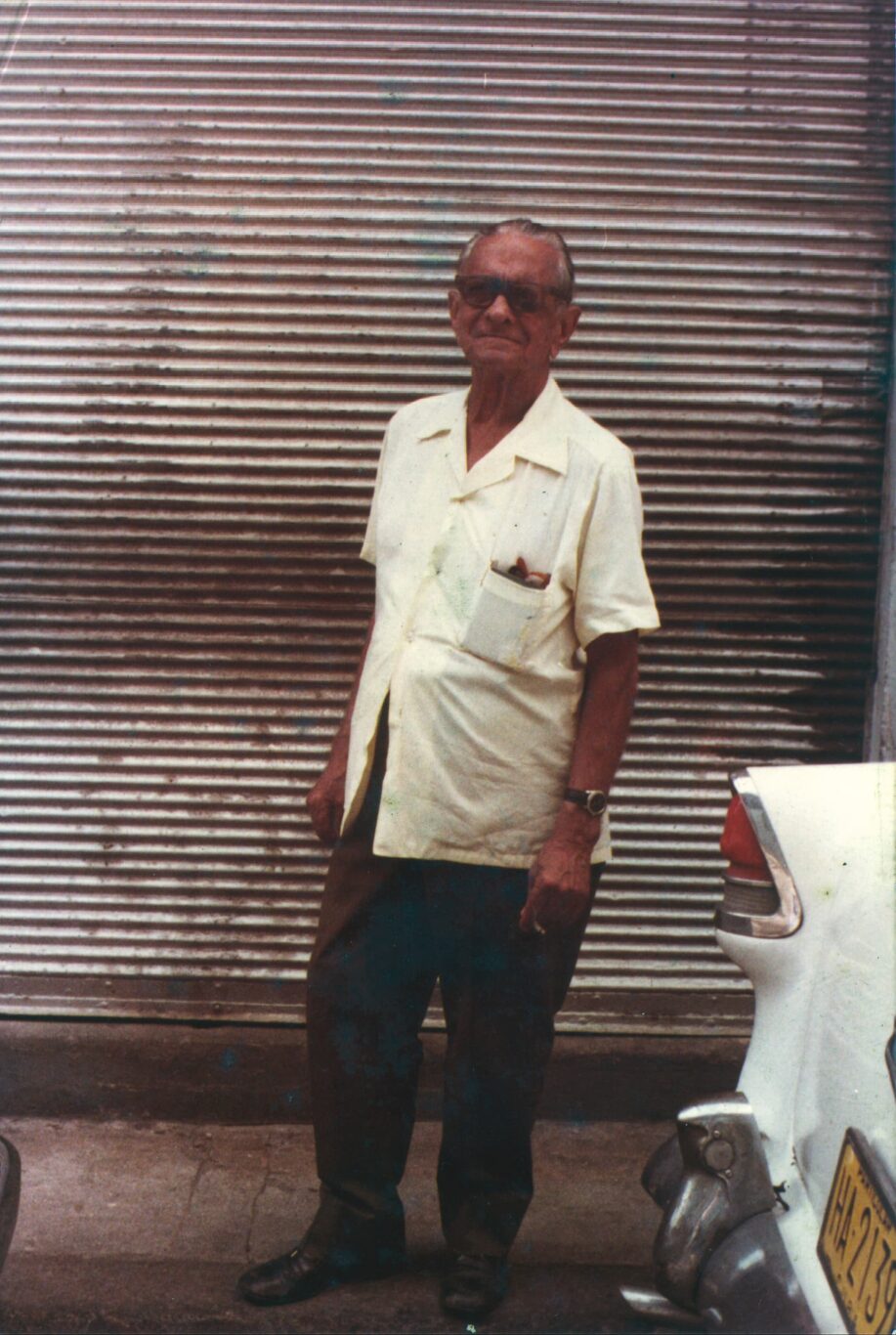

We must also dwell on the legacy of the portraits of illustrious figures of Cuban music: César Portillo de la Luz, Ñico Saquito, Leo Brouwer, Pablo Milanés, Omara Portuondo, Compay Segundo, Ñico Rojas, Miguelito Cuní in the midst of a party, among others. In these images there is no contrived solemnity or bronze rigidity: there is closeness, complicity, admiration and a trust that only exists between peers who share the same profession.

Also appearing are the posed portraits of fellow musicians like Vicente Feliú and Noel Nicola alongside their life partners, Aurora and Liudmila, respectively, where the photograph functions almost as a gesture of extended family, of affective belonging more than historical record.

In a different vein, humor bursts in without warning: Amaury Pérez, with the bull — though not exactly taking it in the conventional sense — reveals that other dimension of the portrait, where irony and playfulness are also part of the identity of both the subject and the photographer.

There are images that I particularly love because of the setting, like the one of the singer-songwriter Lázaro García. The cheerful expression on his face, captured in a domestic and profoundly Cuban context — a clothesline on the porch of a house, a little dog becoming a silent ally in the scene — condenses a poetics of the everyday. Nothing is superfluous, nothing is emphasized: the photograph sings without raising its voice, as if the scene had been waiting, all along, to be seen in this way.

And then there’s that improbable and deeply symbolic encounter between Gabriel García Márquez and Alejandro Robaina, the legendary tobacco grower from Vuelta Abajo. Surrounded by the giant leaves of a tobacco field, the image transcends the individual portrait to become a visual metaphor: literature and the land, the word and its origin, the Nobel laureate and the wise farmer, placed on the same plane of dignity. There, once again, the camera not only records; it interprets, connects worlds and suggests meanings.

The curation of this exhibition by Silvio was handled by photographer Andrés Castellanos, who had to choose the 30 final snapshots from among fifty images. It was no small task. Castellanos framed his interpretation based on “the power of emotions, the power of a gaze when it is sincere, of putting eye, heart and brain in sync while looking through the viewfinder. Photographing another human being is an act of love, and we already know that love is always transformative,” he stated during the opening.

To learn a little more about Silvio the photographer, I’ll close with an excerpt from an interview I sent him a few years ago, in an exchange from one photographer to another.

How did Silvio Rodríguez come to the world of photography?

My interest in photography is quite common: when I was a child, very few people owned a camera. The first time I saw one was in the studio of the photographer from San Antonio, Carlos Núñez, who would later become a prominent photojournalist. In my adolescence, I was fortunate enough to work for different publications and to meet many photographers. At the weekly newspaper Mella, I worked alongside Ernesto Fernández and Peroga; at the magazine Venceremos with Andrés Vallín and Ovidio Camejo; at Verde Olivo with Perfecto Romero, Sergio Canales, Eutimio Guerra and Juan Luis Aguilera. I was a neighbor of Mario García Joya and Marucha for 18 years. And for a long time, I was friends with Alberto Korda. The truth is, I’ve had the luck to know some very good photographers. From each and every one of them, I learned to love and be interested in photography and, of course, in cameras.

In photography, what are your precise moments, worthy of being captured in a photo?

They say that you can write about anything, that the problem is finding the right way. In photography, finding the right way might be when one — or several — of the values that make a photo good come together. There are times when you have to wait for a precise situation to occur, certain lighting conditions, which forces you to take many shots to find what you’re looking for. Other times, it’s enough to simply be there with any device that can record what’s happening.

What points of contact exist between songs and photography?

In a song, there can be an analogy when you talk about everyday life or an extreme situation, like war or a major human event. In any artistic expression, the exceptional has its personality. But although you can take a photo or write a song about anything, the problem will always be whether it’s worth showing.

How do you, a public figure, manage to go unnoticed to take a photo?

There are many places and situations where a singer-songwriter goes unnoticed, especially when he’s not carrying his guitar. And since it’s not uncommon these days for many people to carry cameras, all the better. In any case, when you become a very famous photographer, I recommend the zoom lens.

During the voyage on the boat Playa Girón, you experienced impressive moments. You witnessed a parade of sperm whales, a scene perhaps better suited for photography than for songs. What made you bring, in addition to your guitar, a tape recorder and books, a camera?

Since I was a teenager, I’ve been carrying cameras, usually borrowed ones. For the boat trip, I took a Kiev, which was the Soviet imitation of the classic Leica; a camera with a very good mechanism, still with a coupled rangefinder. My photographer friends at ICAIC (Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry) loaded the film cartridges for me with 400 ASA film. I took about 20 rolls. A couple of them were developed at Mar y Pesca (a Cuban magazine), because when I returned I was interviewed and asked for photos to illustrate the article. I gave the rest of the rolls to a photographer friend who later died, and I never found out what happened to the developed photos. The story about the hundreds of sperm whales was true. We were adrift for a whole day in the middle of the Atlantic, waiting for the procession to pass. That day I shot three or four rolls, but I never saw the pictures.