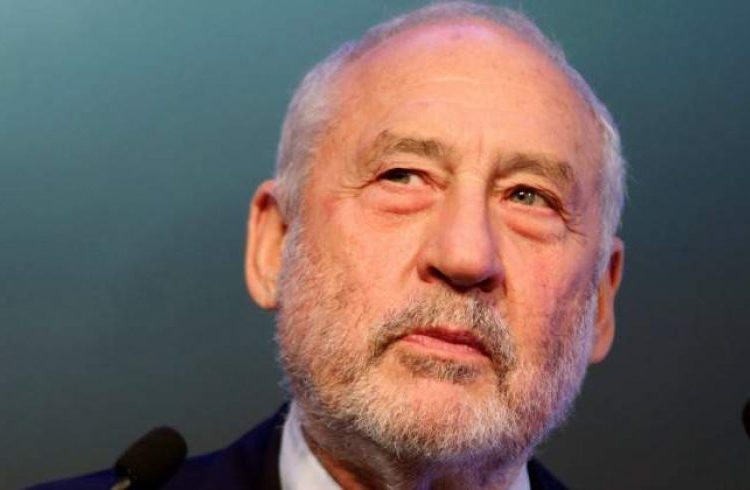

We economists once again had the luck and the privilege of having in Cuba U.S. economist, professor in diverse universities and Nobel Economic Sciences Laureate Joseph Stiglitz.

Fourteen years ago, invited to one of the events on Globalization and Development summoned by the National Association of Economists and Accountants of Cuba, Stiglitz placed emphasis on the inequality of the process of globalization and how the underdeveloped countries, those that were globalized, would be the losers in this new characteristic of the world economy’s development.

For me, his time in the World Bank as chief economist perhaps was the most relevant, especially because it marked new tendencies in that organization and under his direction one of the most notable Development Reports of the 1990s was published, where an in-depth analysis was made of the role of knowledge in development and economic growth. Already by that time – we’re talking of 20 years ago – several Cuban economists had carried out works where the importance of that factor for Cuba’s economic development was demonstrated and also, as a leading factor of those researches, that Cuba had to promote economic policies that would make that advantage really effective.

Again in Cuba, Stiglitz reiterated that that process, understood objectively as the fragmentation of global productive systems and chains, is ineludible and that, compared to what was happening 15 years ago, today it produces negative effects suffered by the poor as well as the rich countries. In short, that globalization’s discontent has also spread to those countries that decades ago seemed to be generators of the process.

But this time he also said that it was possible to find opportunities in that ongoing globalization; that even the small and poor countries could also find winning spaces. He said more, he affirmed: “Cuba is ready for accelerated changes in the global economy” and that’s how it was published by the newspaper Granma.

What are the changes Stiglitz referred to? Actually, in his lecture in the Hotel Nacional, and later in the Aula Magna of the University of Havana he dealt with well-known facts and characteristics of contemporary capitalism, such as:

– The decisive role of the financial economy on the productive economy.

– The change toward an economy where what is decisive is the capacity to learn, or what he called the learning economy.

– The implications of the 4th Industrial Revolution.

– The need for macroeconomic consistency for development and economic growth.

– The existing tradeoff between the way in which the world economy is growing and the growing saving in work posts being triggered by technological development, or what could be called the growing saving in skilled workforce.

– The fact that the work costs have an increasingly lower weight in the strategic decisions of companies.

– The impossibility of repeating the development strategies used decades ago.

– The need to promote the “learning economy” and to develop the services economy that make it possible to create highly-qualified job posts.

– The State will be decisive in the new strategies. But the market cannot be excluded.

– The need to take advantage of the opportunities that the International Financial Institutions can provide while he recognized the fact that they (even the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund) had experienced some favorable changes.

For me – and I believe for some of my Cuban colleagues who for such a long time have dedicated ourselves to studying the problems of the national economy – it is edifying to have so many points of coincidence with Stiglitz, although also as almost always occurs we have our discrepancies with the former Chief Economist of the World Bank. For some years several of our economists have expressed these tendencies and the need to take them into account when thinking about our future development. Dozens of Doctorate Theses and several dozens of articles, as well as books have been written and published about these topics by local authors.

But Stiglitz also spoke of Cuba. He said several things in his three presentations on the island. I will try to synthesize at the risk of forgetting one of them:

– Cuba is prepared to assimilate the accelerated changes in the global economy.

– The changes in recent years have been far-reaching and “we have to rethink the economy,” he added, “but Cuba is well positioned. Its economic development will depend on this.”

– Cuba could develop sectors like agriculture and solar energy. “Cuba, because of its geographical position, has a very rich supply of sunshine.”

– The abundant skilled workforce is an advantage for Cuba.

– The private sector, conveniently regulated, must be a positive factor in development.

– It is possible to take advantage of relations with the IMF, as long as one does not depend on its [the IMF’s] money.

It is true that Cuba has some natural conditions – those that we economists call comparative advantages – to insert itself successfully in these new development tendencies; but above all it has non-natural conditions – those others that we economists call acquired advantages – which, combined with the former would allow for our advantageous insertion.

In fact, the “strategic cores” defined in the documents being discussed today in Cuba are defined based on this: combining those two types of advantages and the world tendencies. It is clear that passing from the word to deeds is more troublesome. Defining what to do is very important, but knowing and putting into practice how to do it is decisive.

Let’s give a simple example: the issuing of knowledge and its structure is really an undeniable advantage acquired based on major educational programs at all levels, throughout the country.

Educational level of the economically active population

2015 Thousands of persons {bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de}

Total 4,979,500 100{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de}

Primary 244,200 4.9{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de}

Secondary 1,131,100 22.72{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de}

Higher intermediate 2,513,500 50.48{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de}

Higher 1,090,700 21.9{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de}

Source: ONEI. 2015 Cuban Statistical Yearbook

However, the per capita GDP is far from corresponding to the quality of that workforce.

It is also true that we must look at the future and try to avert what it seems are already established tendencies that can be – and already are – costly for the future of the country. Cuba has been experiencing a 13 percent reduction of its teaching staff in the last five years. The amount of teachers in classrooms has decreased in Technical and Professional Education from 28,368 to 18,708 teachers, of which those who are university professors have gone down from 20,096 to 15,528 since the 2010-2011 to the 2015-2016 school years.

If we want a concrete case, in tune with what Stiglitz said, let’s take a look at the issuing of knowledge in the Cuban agricultural and livestock sector (measured in amount of intermediate technicians, agronomic and livestock engineers, Research-Development and Innovation Centers). Unfortunately, our Statistical Yearbook no longer gives us information about the quality of jobs in each one of our sectors – very necessary if we want to walk toward that learning economy. However, it is possible to affirm that that issuing of knowledge in Cuban agriculture is perhaps the highest in Latin America and can probably successfully compare to some developed countries. However, the yields per hectare, productivity per man/woman and the levels of production are incomparably lower than in those countries.

It’s true that we have to increasingly create more highly-qualified job posts, but our wage policies do not incentivize the permanence in those posts, on the contrary: they become negative incentives that boost labor emigration toward less qualified and better paid job posts or emigration abroad. And what can be done, if today in Cuba there are more budgeted units than productive enterprises? What can be done, if today 40 percent of employment is still in the budgeted sector and depend on what they produce?

The number of persons employed in what is called sanitation, social and personal services is today 1,948,300 – something like 40 percent of the total economically active population. Today’s entire teaching staff represents 275,242 persons, in health 262,764. Our yearbook doesn’t say if they are considered as part of that sector of sanitation, social and personal services; if it were so and understanding that those two sectors guarantee the present and the future of our development, then the remaining figure would be 30 percent of employed persons in sectors with very low or no productivity. We must change that employment structure if we want to walk toward the learning economy.*

It’s always easier to say it than to do it, but the truth is that all these years of efforts have already achieved certain changes, although not sufficient. A country that grows little and accumulates and invests little can generate very few job posts, that’s why it is important to take advantage of the opportunities, to be more flexible with the national productive sector, with the state-run enterprise – which is still very tied to practices and regulations that limit it -, be more proactive with Foreign Direct Investment, be more dynamic in the promotion of the national small and medium industry…. To promote that all the economic agents feel incentivized to invest in those businesses that are alienated with the country’s development strategic cores. Let all of them be part of this, not just some and others not.

It’s good to listen to Stiglitz, let’s hope we can personally listen to others. It always encourages thinking about our economy and our economists.

* All figures come from ONEI, 2015 Cuban Statistical Yearbook.