Core elements made their lives extraordinary, and deserve to be told. In dialogue with their existential needs and concerns, the virtues of these women managed to overcome the rigid conventions of their historical times and foreshadowed the performances of a world that would come later.

The girl who broke the march

In the light of the centuries, her life seems taken from a vernacular novel. It was around 1880 — when social norms restricted female freedoms and framed women in “the activities proper to their sex”; that is, sewing or piano lessons, and above all, diligently serving her husband and children — that with successful and talented perseverance this Cuban woman outlined her path of predestiny.

Despite being the daughter of wealthy Spaniards, Laura Martínez Carvajal y del Camino stood out for her modesty and willingness to set herself challenges and face adversity. Her intelligence was always that of a child prodigy who learned to read at the age of four and at nine finished primary school with excellent grades. With these words, La Ilustración Cubana would describe it in September 1885:

“A ten-year-old girl, Laura M. Carvajal, took the lead and broke the march, enrolling to pursue studies with academic validity at the San Francisco de Paula school. She is in her second year: she opts, of course, for senior high school, and then…a Doctorate in Medicine or Law. Mr. D. Vicente M. Carvajal, Laura’s father, had to fight against the torrent of contrary opinions and concerns; but the steps taken were so resolute and effective that she managed to overcome the inconveniences.”

Indeed, with an “outstanding” grade in 20 of 21 mandatory exams and leaving the examining board open-mouthed, Laura opened the lock of university classrooms for the female sex on this island, by enrolling in the degrees in Physical-Mathematical Sciences and Medicine at the then Faculty of Sciences of Havana.

But her student years were not a bed of roses. From the first year she had problems attending practical anatomy classes, because given the “crudeness” of the subject she was prevented from participating in the dissections of naked and bloody corpses. The restriction, which at first seemed insurmountable, was overcome by Laura when she convinced the dean of the faculty to allow her to enter the amphitheater on Saturdays and Sundays; thus she was able to learn the secrets of human physiology. Of course, she had to be accompanied by a family member.

She combined her theoretical and practical period by caring for poor patients at the San Juan de Dios Hospital until, after accumulating a series of uninterrupted successes and an overwhelming record, on July 15, 1889, just before turning 20, she became the first Cuban woman to graduate in medicine, and immediately afterward she began her studies in ophthalmology.

In 1889 she married the ophthalmologist Enrique López Veitía, who initiated medical congresses in Cuba. Together they made a career, published books and founded the medical journal Oftalmología Clínica, expanded their research and set up a private ophthalmology practice, which is why Laura is also known as the first Cuban woman to practice this specialty. Her dedication as a doctor and mother of seven children was combined with knowledge of music, plastic arts, literature and botany. She was fluent in English and French.

Involved in various philanthropic endeavors, she joined the Bando de Piedad and the Sociedad Protectora de los Niños de la Isla de Cuba, an organization that cared for abandoned children. In addition, with one of her daughters she founded a free school for the poor on the El Retiro estate, in the jurisdiction of El Cotorro. There, without stopping working, she ended her fruitful life on January 24, 1941, weakened by tuberculosis that months earlier had taken her husband and daughter to the grave. The press, focused on the course of World War II, barely mentioned her death.

Laura Martínez Carvajal is remembered as a model of female scientists and a paradigm of women’s perseverance in the fight for professional rights. Even overcoming the prejudices and mental barriers of the 19th century, she managed to fulfill her dreams of saving lives and being useful to society.

Evocation of Consuelo

“It is time for us to stop washing dishes,” she seemed to proclaim in every newspaper article or academic speech, as if she were seeking to reverse the narrative that blacks were suffering beings predestined to the hardest work and to live burdened by torments and discrimination of all kinds. Obviously, along the way she had to face racial grievances and misunderstandings for her vindicative spirit, but although in the end she did not obtain all the recognition she deserved, the work and the name of Consuelo Serra Heredia must be remembered for her uniqueness.

Daughter of Rafael Serra Montalvo, patriot, journalist and defender of racial equality who was a great collaborator and friend of José Martí, Consuelo was born in Matanzas on July 13, 1884. She was just a child when she emigrated with her family to the United States.

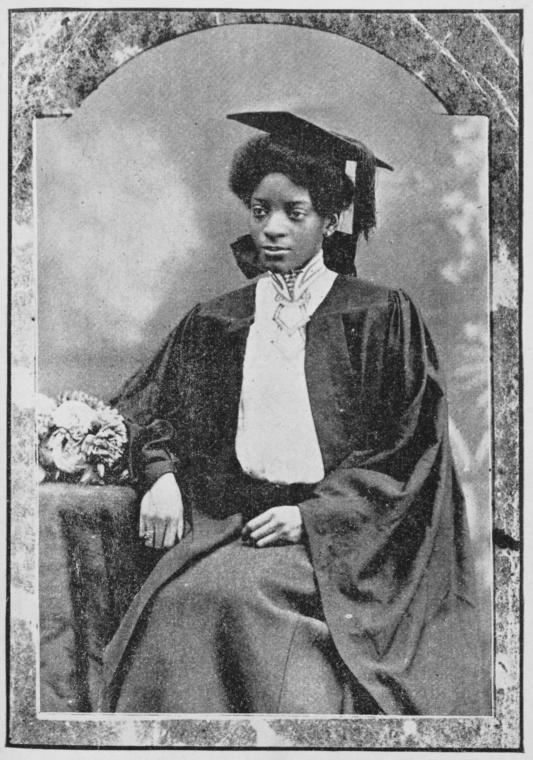

She studied teaching for five years at the New York Normal College — now Hunter College —, graduating in June 1905 with a PhD in Pedagogy.

Back in Havana, she founded a private school in October 1912 and taught English at the Normal School for Teachers in 1921. Her experience there inspired her book libro Para mis alumnas de la escuela Normal de Maestros. At the same time, she enrolled at the University of Havana with the aim of validating the academic degrees she had obtained in the United States and also earning a PhD in Philosophy and Letters.

The school she founded was located on the outskirts of Havana, in Arroyo Naranjo. While the pedagogical panorama of the Republican era was based on pre-established molds, she noticed with her extraordinary wit that the study plans led to the formation of fragmented brains. Under her guidance and managing to bring together an excellent group of teachers, rather than comprehensive instruction in science, arts and moral values, they offered warmth of home to their disciples.

In a letter written in 1937, one of her former students assessed: “The work carried out by this educator near us here in Cuba, we understand that it is of the same quality as that carried out in her country [the United States] by the illustrious educator Booker T. Washington, in that both, in very unfavorable circumstances, proposed the great task of teaching the race a more effective way of approaching present civilization and life. And in that endeavor, Dr. Serra has sacrificed her youth, her intelligence, her wealth, everything.”

The Consuelo Serra Home School ceased to exist in 1961, when the country’s private academic institutions were nationalized. A few years later it collapsed, according to a magnificent text by Josefina de Diego, also a former student of the school.

Consuelo Serra collaborated with different press organs of her time. She wrote the sections “Pedagógicas” in the magazine Adelante (1936-1939) and “Ideales de una Raza” in the Diario de la Marina. In reference to the virtues of black people and the need for respect and unity among all, she maintained:

“We must spread our values, since, fortunately, we do not have to create them (as we can be legitimately proud to say) as they have always existed in the minds and hearts of our elders. A dignity for which we feel the legitimate pride of being Cubans and of being black, because we black Cubans have done many good and respectable things in all stages of life, and not always in a mediocre way, but in a distinguished and outstanding way. Our elders have left us these virtues, these ethical values. It is up to us to collect them and place them on high, so that everyone can see them and so that peace and unity can be achieved among all Cubans.”

As a child, Consuelo Serra met Martí. He kissed her forehead, gave her La Edad de Oro, and in the book, little Consuelo understood that “girls should know the same as boys, so they can talk to them as friends when they grow up.”

As one more mystery of childhood, she was fascinated by that man with an apostolic halo, who plotted tirelessly and enamored everyone in favor of the independence of Cuba. “Whether I am here or there, act as if I were always watching you. Do not tire of defending, or loving. Do not tire of loving. A kiss to Consuelo,” Martí said goodbye to Rafael Serra and his family on January 30, 1895. He was leaving for the battlefield, to preach with his death. Simple and austere, Consuelo Serra lived an apostolic life in her own way.

Cielito lindo

At 18, Berta Moraleda had already put her name in the heavens. She would remember it many years later, when she brought her memories to life in a nostalgic interview with a Bohemia reporter (see issue of January 24, 1975). Similar to the pirouettes of a drifting airplane, hers was a life marked by strange zigzagging paths.

It all began on May 23, 1930, when, following in the footsteps of Raymonde de Laroche — a former Parisian theater actress who was the first licensed female pilot in the world — young Berta received her pilot-aviator title in Havana. In this way, she received the honor of being the first Cuban woman authorized to fly an airplane. Although it is valid to clarify that the first lady to conquer the skies of the island would be the also French Madeleine Herveux, who in 1921 flew from the airstrip at the Columbia military camp.

“One must imagine the kind of intrepidness this woman had to fly one of those devices, the Curtiss Fledgling, a conventional U.S.-made biplane, initially designed for the navy and later used as an air taxi and training aircraft during the 1930s,” notes the master of photojournalism Jorge Oller in his article “Alas femeninas.”

“Based on the Curtiss aviation school,” the author continues, “which was located in Rancho Boyeros, on the outskirts of Havana, the Cuban Berta Moraleda was trained by the French aviator France Harrel, one of the few women who had a pilot’s license in the world at that time. She then made her first solo flight without an instructor and was accredited after 53 hours of training. She went on to perform aerial acrobatics and accumulated more than 200 hours of flight throughout her career. She was undoubtedly a bold pioneer who demonstrated, just like our contemporaries, that for women there are no limits, not even when flying through the skies.”

The curious thing is that before reaching glory she was a simple telephone operator for Panamerican Airways. The change came as a result of influence peddling and a company official demanded that the girl be fired to give the job to a U.S. friend. But faced with the crossroads where others saw a defeat, Berta found the opportunity of a lifetime. This is how she told it to Alcides Iznaga, the Bohemia journalist:

“I was the breadwinner of the house. My father, Guillermo Moraleda, was a typographer, a Marxist, and a friend of Alfredo López, with whom he was imprisoned and held incommunicado.… My dismissal was a rude blow for me…. And I thought about flying, about the possibility of dedicating myself to that activity, where I would not have to fear for my job, once I had it. At that time, the Curtiss Aviation Company established a school at the Rancho Boyeros airport, and I decided to enroll in its first course. I faced two obstacles: my father’s refusal and the financial problem — I didn’t have a cent —, the course cost 2,500 pesos!”

When there was only one hour left before the scholarship deadline, the stubborn Berta managed to obtain the consent of the suspicious father. She then ran to the office of Alfredo Hornedo, the main owner of the Excelsior and El País newspapers and a shareholder in El Crisol, and proposed that if he paid for the course, she could later pay him back by working for his newspaper or by airlifting the matrices that were printed in Santa Clara; not to mention the lucrative benefits of having the first Cuban female aviator at home. The magnate, who was no fool when it came to business, found the promise interesting and put his checkbook on the table.

She was brave in the air as she was on the ground. With the same recklessness and determination, she faced challenges and accidents inherent to the profession: “I once experienced a minor forced landing,” she would confess. “When I heard a strange noise from the engine, I began to fly over a sugarcane field; then, when I was about to end the flight in a dangerous manner, I remembered that my instructor recommended that we avoid emergency descents as much as possible and, quickly, I started the plane again…with great effort I was able to land!” The winds did not always blow in her favor and in the end the dream fell into a nosedive.

“Aviation was always an important part of my life. It is a pity that it lasted so little,” she lamented. However, when Alcides Iznaga discovered her, wrinkled and forgotten in her old house, she still remembered with pride that every time she taxied down the runway towards the clouds she began to hum her flight melody, anthem of identity: Ay, ay, ay, ay… canta y no llores. Porque cantando se alegran, cielito lindo, los corazones.