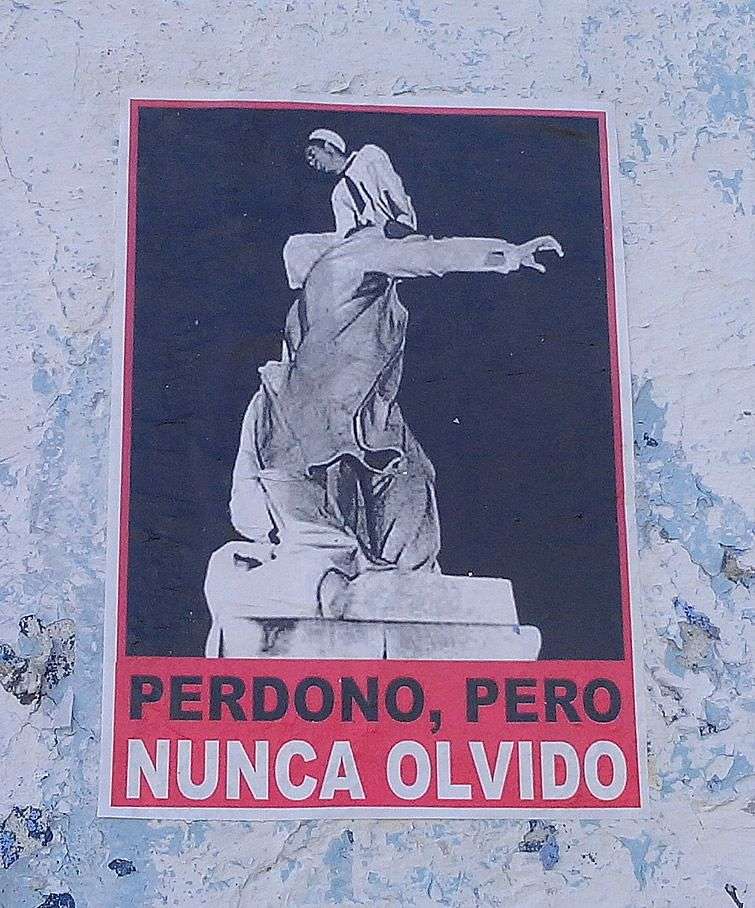

I bumped into this poster while walking along Línea Street:

The image of the photo is unmistakable; it belongs to the country’s collective memory: the act of insulting the monument to Martí in Havana’s Central Park on the night of March 11, 1949. The U.S. marine climbing at the top is Richard Choinsgy. According to history he and his mates – Sergeant Herbert D. White and marine George J. Wagner – were monumentally drunk. They had just come out of Sloppy Joe’s Bar, barely two blocks from the place of the event, and they were furious.

Choinsgy wanted to demonstrate his acrobatic skill by climbing the monument to the Apostle of Cuban Independence, from where he seasoned his feat greeting his colleagues and the growing amount of public gathering around the scene. He was forced to come down because of the bottles and stones people threw at him. A mob attacked them. Only the intervention by the police forces prevented the alleged lynching. The police officers had to whack the violent ones with their billy clubs and shoot into the air to take out the attacked unharmed and take them to the First Station of the National Police.

The national press reported these events on the following day. Fernando Chaviano, an amateur photographer who was passing by the place while the profanation of the monument was taking place, took the only two shots conserved of the event. The images, as always, have an incomparable mobilizing weight: the whole of Cuba boiled during those days, when the condemnation of the U.S. marines, including the peaceful tourists, and even the stoning of the U.S. embassy that occurred the following day in the midst of a spontaneous protest in its vicinity, forced the diplomatic representatives to hurry up an apology.

But, what is this image doing in the Havana of 2016? Why is a slogan like “I forgive, but I’ll never forget” being placed on the fabric of the present and recontextualizing its meaning?

This printed matter is not signed; no one is explicitly responsible for its creation and spread. Moreover, “23rd Street from Paseo to 12 still exhibits a few of them intact, almost always pasted in the back of traffic signs or on street lamp posts. I have dedicated myself to seeking them in other areas and I was barely able to find several of them, almost all of them worn out or covered by signs for reggaetón concerts or house swapping ads, on the Calzada de Infanta, along the way from Zanja to San Lázaro.

From the above it is understood that its creators and those who paste them around wanted to make it very visible, placing them in the capital’s centrally located streets. As is clear the intention of dialoguing with the special circumstances of the new national historic moment. At a time of goodwill and rapprochement, “thawing” they say, with the neighbor to the north, to “bring off a coup” seems like a revanchist attitude.

The comment, by the way, demonstrates the absence of consensus regarding how to assume the new relations with the “historic enemy of the nation.” While a considerable part of society embraced the rapprochement with relief and enthusiasm, another almost immediately issued their suspicions. While the imagination of the popular culture started producing gestures of approval, the city filled with the flags of stars and stripes and a capricious but picaresque mutant was born – again an image -, where two significant opposites joined, baptized as Mickey and Valdés, another area, especially close to the discourse of political power, raised objections and warnings.

Does this image have something to do with a campaign devised to highlight that purpose?

Probably. But more than devoting oneself to establishing in-depth intentions, I prefer to better observe its means of support. The image of the insult to the image of José Martí was profoundly planted in the structure of Cuban nationalism. Because it represents, fast and loose, an attack on the Cuban nation, any Cuban, no matter where they live or how they think, repudiates the act.

But more than half a century after the event, stripped of its contextual meaning, of dates, collection of anecdotes, circumstances, the image remains; an image that is read as the symbol of historic relations between unequals, where the powerful sullies the weak. And nationalism, whether used for the exclusion of the different or to highlight resistance in the face of forces external to the will of a compact social group, in general operates with high proportions of emotion.

When nationalism maneuvers with such images it uses them for its vindications. In Vietnam they have the photo of the naked girl burned by napalm. In Panama, the ruins of the genocide of El Morrillo. In Okinawa, dozens of documented cases of raped girls and women. In Ecuador, a black spot in the middle of the jungle. It’s always about the small one’s demand in the face of the big one. Frequently, it’s about using reasons from the past to seek protection in the face of probable future abuses, sustained in an order of things that justifies the historic suspicion.

“I forgive, but I never forget.” This here is a declaration opposed to amnesty. A serene and powerful rationality – because you have to have a very high human and moral density to forgive so many insults without succumbing to the grudge or vengeful predisposition – indicates that absolving by erasing the past would be irresponsible. The tension in the Cuba of today to forget and forgive or to evoke with emphasis, could never ever relinquish those images, since they remind us of the humiliating situation that led us from one thing to another, and brought us to this point.

Because on March 13, 1949, two days after the scandal of the Central Park, as a measure to avoid other incidents, the flotilla of the U.S. Navy on which the inebriated marines came to Havana weighed anchor. The departure also prevented those who committed the crime from being tried by Cuban courts, as the protests demanded. Days later the sanction against Choinsgy would be known: fifteen days without leaving the minesweeper where he served. That is, two weeks without a pass. And let’s make a fresh start.

But nationalism has unforeseeable aspects. Sometime before I saw this other poster on Línea and 8:

This image doesn’t come with any legend. It just contains a very well-known picture: that of Antonio Guiteras, a strange individual within the Cuban socialist, revolutionary, anti-imperialist tradition. Guiteras is especially known for his post as Secretary of Government, War and Navy during the One-Hundred-Day Government starting September 1933. But in Cuba almost nothing is said about him. He is not celebrated. This exhumation, on the back of the bus stop sign for the P1, P5 and 20, is, to say the least, strange.

Guiteras’ photo has been, as will be seen, modified. A kerchief covers his face, perhaps vindicating his reputation for being rebellious, in favor of a “Jacobin socialism” (as Julio César Guanche describes him), for choosing the violent option more than once. Or because of that radical behavior that led him during his 100 days in government to do more than many people had done in years: he institutionalized the unions, established the minimum wage and the eight-hour workday, workers’ insurance and retirement, as well as repudiating the debt with the Chase National Bank, he nationalized the Cuban Electricity Company and removed U.S. Thomas Chadbourne from the presidency of the National Sugar Exporting Corporation, among other many measures in favor of the Cubans’ interests.

So someone brings back to the present a man among whose legacies, in addition to the deepest nationalist option, is expelling from his office the United States of America envoy and combating in all senses the complex of colonial inferiority of the country’s local people.

These days the city has all types of posters, and from their silence they ask questions.