When I arrived in Hialeah, I had the feeling I hadn’t left Cuba. The same Spanish spoken in the streets as in the island’s neighborhoods. There are no English translations on the shop signs; nor are there any travel agencies advertising packages and tickets to Havana in neon letters, nor are there any clothing stores or specialty stores, where the music of Los Van Van or Willy Chirino blares.

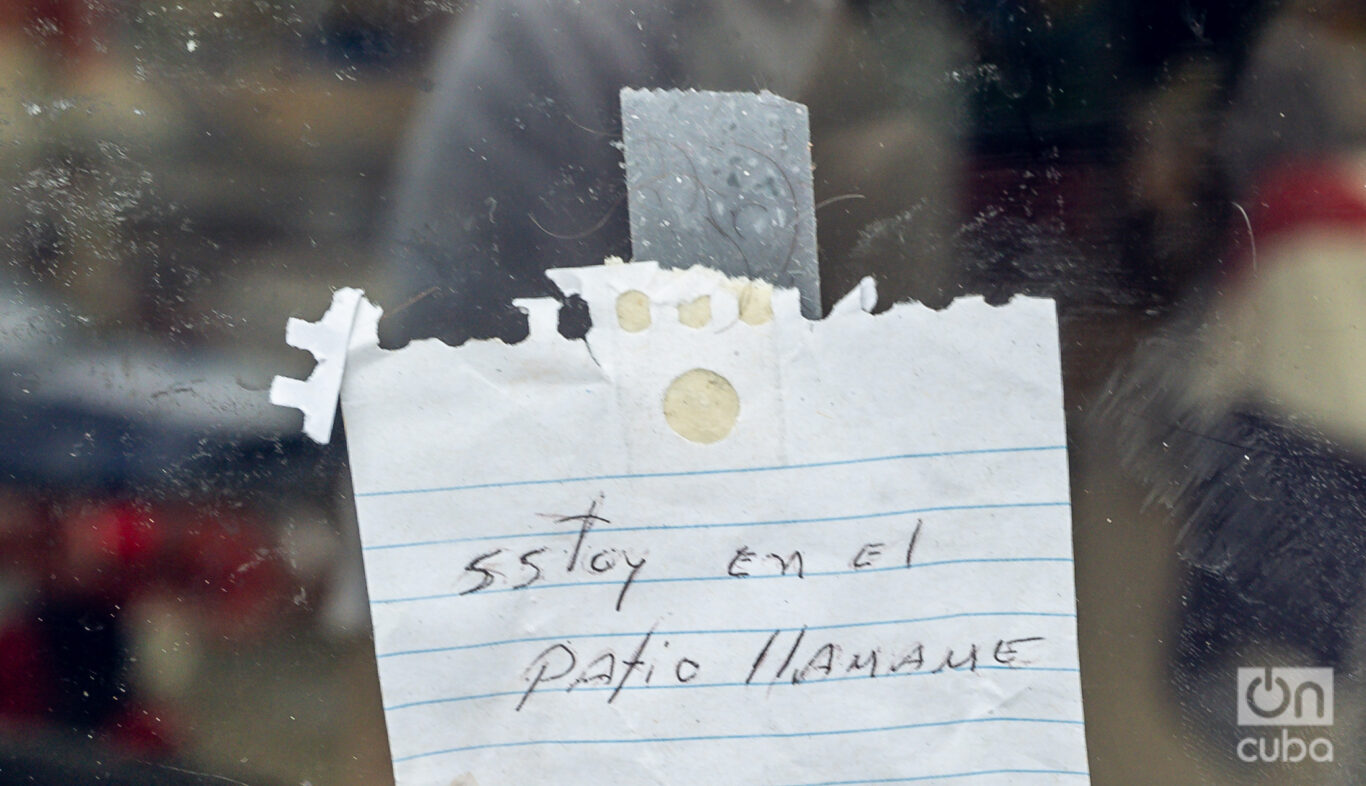

Hialeah must be one of the very few places in the United States where you don’t need to speak English. Unlike other areas of Miami, where they first greet you in English and then, upon recognizing your accent, switch to Spanish, here the entry language is directly our own. English appears only in the occasional stray expression, almost like a compass reminding us we’re in the north.

It happened to me at the famous Palacio de los Jugos, where signs offer mamey, mango and guava smoothies, yuca with mojo sauce, malanga fritters, and chicharrones, as if it were a farmers’ market in Centro Habana. Or at the famous “Ñooo qué barato” store, known as the “Cuban Walmart” because there you can find everything for Cuban families on the other side of the pond. There’s no trace of American sobriety: everything is color, noise, excess, that way of being in the world that we Cubans carry with us even when we cross borders.

To my ear, “Hialeah” was a familiar name before I ever set foot there. As a child in Cuba, I heard it from neighbors, friends or relatives returning from the United States. Many claimed to live there. It was like a word that brought news from across the ocean, laden with dreams of migration.

This is no coincidence. According to the latest census, 96.3% of its inhabitants identify as Hispanic or Latino, and more than 75% are of Cuban origin. That’s why some U.S. media outlets dubbed it “the least diverse city in the country.” The phrase seems contradictory, because what one breathes here is precisely Latin American cultural diversity, but it’s true that Cuban predominates, almost erasing any other trace.

Founded in 1925, Hialeah began with just 1,500 inhabitants and a name of indigenous origin that means “Great Prairie.” This image of open, green lands contrasts with the city today, which has become an industrial and working-class hub with more than 230,000 residents.

History has held moments of singular significance for Hialeah: from the departure of aviator Amelia Earhart in 1937, in her attempt to circumnavigate the world, to the filming of scenes from The Godfather Part II at its racetrack in 1974. Even its flamingos — the city’s symbol — arrived from Cuba in 1934 and eventually became its official emblem.

But what truly transformed Hialeah was the wave of Cuban migration. Beginning in the 1960s, following the triumph of the Revolution, thousands of my compatriots settled in this corner of Florida. Then, in the 1980s, those who arrived with the Mariel boatlift joined them, and in the 1990s, those who arrived during the “rafter crisis.” Many chose Hialeah because they already had family or friends in the area, and because here they could speak, work and survive without giving up their culture or learning English.

That’s why the city adopted the motto “The City That Progresses.” And yes, it progressed, but it did so in its own way: based on the efforts of workers, Latino-controlled textile factories, clothing and mechanics workshops where Cuban and Central American labor sustains the local economy. Hialeah is, at its core, a working-class city.

It’s tempting to describe it as a “little Cuba” in exile. But the city is more than that: it’s a laboratory of identities, a space where what it means to be Cuban, Latino and American at the same time is negotiated every day.

Some see this cultural homogeneity as a limitation; others, a strength. It’s paradoxical: on the one hand, it represents the continuity of Cuba beyond its borders; on the other, it proves that migration is also a way of founding cities, of redefining spaces beyond borders.