Cultural exchange between Cuba and the United States has been one of the Trump administration’s first targets regarding the island.

In August 2024, the U.S. Embassy in Havana reactivated the possibility of processing work and exchange visas, including those for international cultural exchange programs. In February of this year, a month after Trump took office, his administration returned dozens of passports without a visa because they had been processed by Cuban government agencies.

At the time, Cuban Deputy Foreign Minister Carlos Fernández de Cossío told the AP that with this gesture, the U.S. government “announced that it is suspending the application process for a group of visa categories used for government officials and their agencies,” asserting that the decision “directly affected bilateral exchanges that were taking place in areas of mutual interest and benefit to the peoples of Cuba and the United States, such as culture, health, education, science, and sports.”

This measure not only compromises the ability of Cubans to visit the United States for activities in these areas. Two weeks ago, the federal government canceled a trip to the island for a jazz band from a Vancouver, Washington, school. The Office of Foreign Assets Control informed them in a letter they received as they were preparing for their flight that their trip “would be incompatible with the policy of the United States government.”

In this context, the fact that Pacific Standard Time, the main jazz choir of the Bob Cole Conservatory of Music at California State University, Long Beach, has managed to reach Cuba and carry out a program of performances and exchanges with Cuban artists and music students, has been something of an oasis in the desert.

Making the visit a reality was in the hands of Royce Smith, Dean of the College of Arts at the university, for whom cultural exchanges have become a life goal for more than a decade.

“I think my interest began with the ban. When someone tells you that you don’t have the right to go somewhere, it sparks interest; it has the opposite effect on the soul of a creative and curious person,” Smith told OnCuba.

A week to change perspectives

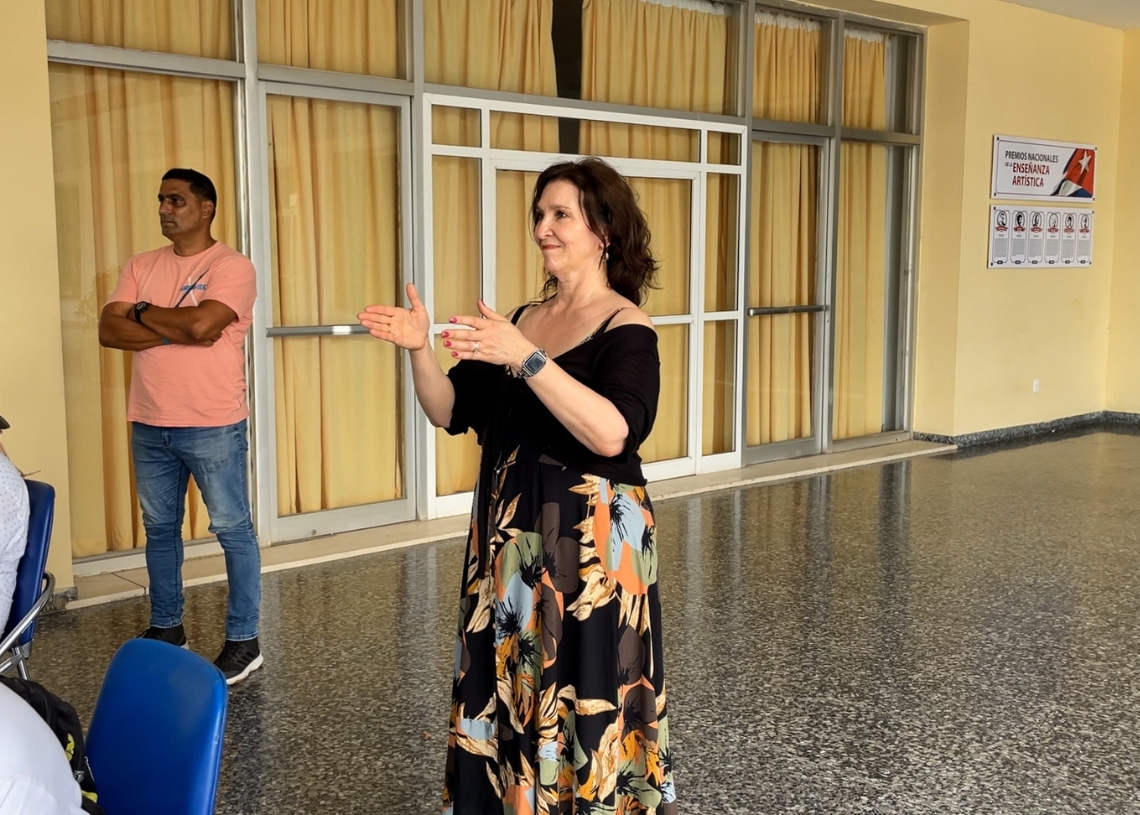

“I really feel like my perspective on life has changed,” sums up her experience Maggie Robertson, one of the singers of Pacific Standard Time, made up of 13 voices, a musical base with bass, piano, and drums, and directed by maestro Christine Guter.

During their week on the island, the group gave four concerts in very diverse venues, a program of performances designed to reach diverse audiences: the Hotel Claxon, the University of the Arts, the National Museum of Fine Arts Theater, and the Fábrica de Arte Cubano.

The high quality of their musical proposal is unquestionable and is backed by 14 consecutive years of winning the DownBeat Student Music Awards, the most prestigious awards in jazz education in the United States.

“I like to choose repertoire that is inspiring, uplifting, and healing. It’s important for musicians to also be healers, because the world is so conflicted right now, and we want to contribute something good,” says Christine Guter, who, like the rest, was visiting Cuba for the first time.

The group went to the Manuel Saumell Elementary Music School, exchanged with the Cuban National Choir at its headquarters, attended a concert by Isaac Delgado, and received master classes in popular music and Cuban percussion with musicians from the Los Van Van band and Yaroldy Abreu.

Every minute was made the most of to make this a tour of true appreciation for Cuba and its culture.

“We love Latin music, and Cuban music and jazz are very intertwined. We have a lot to learn about Cuban music and culture. I thought it would be a truly wonderful opportunity to learn from you and to share our music with you. It has been incredible, nothing we could have imagined,” Guter said.

Theirs is a collective approach that manifests itself in diverse ways, as each member takes home a personal experience.

For Ace Homami, one of the voices of PST, what impressed him most was “the people, the music, the art in general, which is not only within the art scene itself, but throughout Cuba. There have been so many moments where I’ve looked around and thought how incredibly lucky I am to be here to experience this culture, this atmosphere.”

“Being in Cuba has been one of the most enriching experiences of my life. It’s been crazy how many things have happened that are so different not only from what happens in the United States, but from what I thought they could be. And it wasn’t just enriching musically, which it was, but enriching for my soul, for my personality, for me socially,” Robertson explains regarding the aforementioned change of perspective.

Perhaps one of the strongest feelings was experienced by Max Smith, the grandson of Cubans who emigrated to the United States in the 1960s. He is the first in his family to travel to Cuba since then. His story was shared on every stage where he performed.

“It’s incredible to be here, to experience this, and to connect with my roots and the culture I’d never been in contact with before. The people here are very generous and have made that connection possible for me; they’ve made me feel welcome,” Max told OnCuba.

Perhaps the most meaningful thing for him is the vision of the island in which he landed here and what he has to say upon his return.

“It’s very different from what I’ve been told about Cuba; I think it’s very different from what it was like in the 1960s. I’ve been able to learn a lot about the people, the food, and the music. I’ll tell them to come and see for themselves.”

Giving and receiving

In 2011, Royce Smith arrived in Cuba with a group of students to visit the Havana Biennial. Since then, he has included contact with the island in his career as a teacher and curator.

He is currently the Dean of the College of Arts at California State University and has also held this position in the College of Arts and Architecture at Montana State University-Bozeman. He is a professor of art history, and his work as a curator has included him in important biennials, such as the one in Asunción, Paraguay, the one in Curitiba, Brazil, and the one in Havana.

“I started speaking Spanish when I was 12, and my parents taught me that there are many more people who have the right to call themselves Americans, who live in other parts of the Americas, that it is plural. And from that moment on, an interest in exploring that world was born, and Cuba as well,” Smith says.

“I spoke with my students, and we discovered that, using the connection of music and the visual arts, we always had the right to move from the United States to Cuba. The arts have always been the bridge between the two countries. And using that, we have tried, through collaborations with Cubans and Cuban institutions, to create more ties, more opportunities for exchanges,” he says.

As a professor and dean, he does his best to allow his students to have experiences like this.

“A university is a space dedicated to developing the wisdom of various disciplines, because artists have to be masters of their own techniques. But the question is how they translate that wisdom to a completely different cultural context, one with its charms, its history, its specific practices and customs.

“And the students learn flexibility, they adapt to the Cuban rhythm. That’s super important, because they have to find, discover another part of their artistic soul to be successful. There’s something that’s been awakened, which I see in their faces, in their way of presenting themselves, of expressing themselves. And that’s truly the gift that Cuba has given them.”

But it’s an exchange; it’s about giving and receiving.

“I always want to dedicate myself to creating a world where we can collaborate. We are neighbors. We share stories, experiences, oppressions, successes, goals, visions, and it’s been that way for hundreds of years. We have to respect each other, be honest, open, listen, and have patience.

“My goal is that through the arts we can soften that relationship a little. We have a responsibility to be leaders in peace, in conversation and dialogue. And I’m committed to doing that with my students, with my own professional practices. And that’s why I love Cuba,” Smith concludes.