Like that of doctors, the job of some economists is, in essence, to examine a body suffering from certain conditions; identify them, find their causes using experience and sometimes sophisticated analyzes and instruments and then prescribing remedies with a specific method for their administration. Like doctors, economists do not treat illnesses, but rather the sick.

2023 will end shortly. We will soon have information about what this year has been like. However, it is possible to advance some ideas in this regard and look at the way forward.

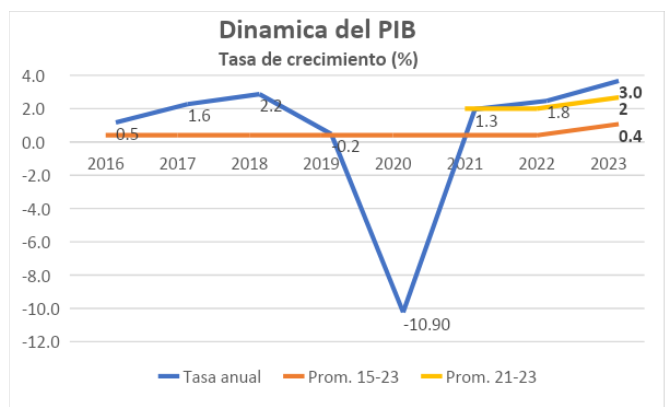

Regarding the GDP growth dynamics, what is most striking is the absence of public information on its quarterly behavior, because in the usual official information behavior, it has been customary that the absence of public official information corresponds with unwanted results. In this case it would translate into growth below what was planned or in results that return the GDP growth rate to red numbers.

What the data show is that in the last two years the recovery has been moderate. What the projection that appears in the graph above says is that, assuming that this year the economy grows at a rate of 3%, the average GDP growth of the last three years would barely reach 2%.

If this average annual rate is maintained, seven years from now, in 2030, a per capita income would be only 14% (697 CUP) higher than this year that ends. It is something that seems sociopolitically unsustainable, especially if we take into account inflation trends.

If we look at the information made public about the different sectors of the economy, the prolonged power outages, the persistence of very strong restrictions, imports and the non-compliance with the tourism growth forecast, it is unlikely that the goal of 3% growth in 2023 will be achieved.

From the macroeconomic perspective, the factors that can theoretically contribute to product growth can be placed in two groups: those that depend on internal resources and those external resources that can be attracted by the country.

Gross capital formation and national investment are those internal sources. The gross capital formation rate (15.8 average between 2019 and 2024) and the investment rate as a proportion of GDP (9.5 annual average between 2017 and 2024) present very discrete behaviors. In both cases they do not reach the levels needed. On the other hand, the sources from which they are nourished: domestic savings, does not seem politically feasible to increase it at the expense of reducing consumption even further.

Income from exports, foreign investment, external credits and remittances. All these external sources are diminished. They depend on external factors on which it seems extremely difficult to act, such as the U.S. blockade, the evolution and trends of world trade and the existence of armed conflicts in various regions of the planet.

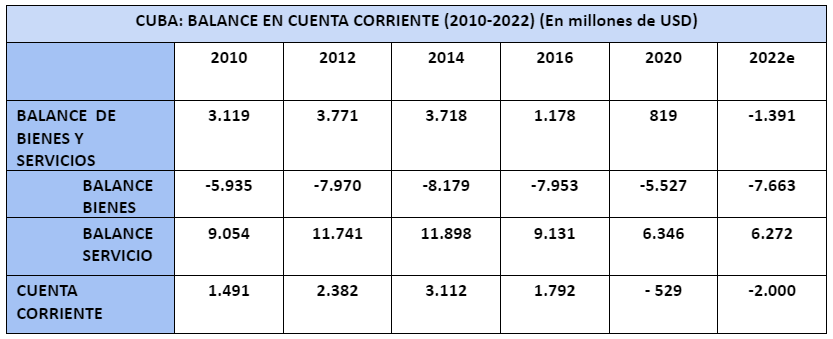

In the case of export income, the balance of goods remains negative and the current account balance in both 2021 and 2022 is estimated to be negative, which substantially reduces financing sources.

The attraction of foreign investments is estimated to have not exceeded 600 million in 2020 and 2021. It is likely that in 2022 the figures for executed foreign investment will have improved, but even doubling them would be very far from the real needs, which today must be greater than those 2.5 billion annually, which years ago was considered necessary to grow at 5%.

The withholding of the dividends of foreign investing companies, as well as macroeconomic distortions and the dynamics of inflation act as a disincentive and add another dissuasive effect on the intentions of new investment proposals, already diminished by the extraterritorial laws of the U.S. government.

Meanwhile, access to external credit is limited by the payment capacity (debt service reaches practically all income from exports of goods) and by the high country risk that Cuba represents.

While considering the GDP at the rate of one Cuban peso equivalent to one dollar, Cuba’s debt levels (debt/GDP) do not seem alarming, if the exchange rate adopted with the Reorganization Task is used, which would deflate the product, the results would be drastically different. In any case, what we are dealing with is the country’s very limited payment capacity and the delay in causing structural changes that avoid continually falling into debt cycles.

Remittances, a traditional source of growth, have been reduced and are now estimated at less than US$1.5 billion.1 The structure of destinations has changed from its almost absolute concentration in demand for final goods towards small investments in the non-state sector.

The weak flows of external capital and the difficulties in accessing external credit indicate that for the short and medium term the internal effort is decisive. This compromises the future, as it reduces the possibilities of growth via modernization of the Cuban business system.

The state enterprise, responsible for 80% of the GDP, and more than 70% of exports, faces often disproportionate challenges and a decisive part of the wealth it produces is continually extracted.

If the contribution from the investment and the payment of taxes is taken into consideration, 73% of income between taxes and contribution from the return on investment is extracted from this actor, the decisive one according to all discourses, even when at times the corresponding assets for which you must “contribute” are more than depreciated and amortized.

This means that state enterprises only have about 27% of their income left, of which half must be distributed among their workers; while any investment, modernization, research and innovation efforts must be financed with the remaining 13%. It is another reason that explains the deterioration of the state business system. The scarce and poorly regulated competition between state enterprises is another factor that would explain these results.

From the microeconomic perspective, issues such as efficiency and productivity of the state business system reappear as factors that negatively influence growth aspirations. For example, only 56 enterprises (2.3% of the total state enterprises) concentrate 80% of the profits and 587 enterprises (24.5% of the total) are in losses or with profitability below two centavos.2

According to the 2022 Statistical Yearbook of Cuba, the contribution of state enterprises to budget income rose from 21,782,700 in 2021 (13.4% of non-tax income) to 27,231,100 in 2022. (21.9% of non-tax income); this means an increase from one year to the next of 25%.

However, the contribution of enterprises only amounted to 10.7% of total gross income. Compared to the fiscal deficit, the contribution covers 38.6% for it. Extracting 10% more from state enterprises would raise that coverage to 42.5% of the deficit; that is, about 4 percentage points more. Although short-term emergencies seem to push towards this decision, it is necessary to ask whether impoverishing state enterprises even further is convenient from the perspective of economic growth.

Extractive institutions are, without a doubt, one of the causes of the impoverishment of countries. In Cuba this has been a totally “natural” practice, due to a combination of tradition and necessity. The “rentism” that these institutions reinforce does not resolve the situation and always compromises the ability to grow. Both constitute negative incentives for the intention to invest and consolidate the culture of inefficiency that makes those enterprises that are efficient and productive pay high costs, and reward those that are not.

On the one hand, a relatively small tax base that forces the tax burden on taxpayers to increase and reduces available income, part of which should be invested; on the other hand, the need for the State to assume an important, although decreasing, fraction of the satisfaction of the needs of citizens, who are not able to meet an increasingly growing part of their needs with their personal income. All of this makes budget management an exercise in “miraculous statics.”

Without a doubt, increasing tax revenues should be part of a macroeconomic stabilization program, but it becomes procyclical if this increase occurs via an increase in the tax burden on those who produce wealth.

On the other hand, reducing spending becomes a kind of political engineering exercise that involves eliminating subsidies for certain products and enterprises, something that would seem too politically costly.

However, the economic history of our reform process demonstrates that failing to do so will be more costly in terms of economic growth, especially if we look at the levels of efficiency and productivity that are achieved both in the state business system of the economy, as well as the excess of people (bureaucracy that often becomes one of the main causes of “destructive resistance”) and the poor use of the work day in the budgeted sector.

If we look at the structure of the entities, today there are more entities in the budgeted sector than in the state business sector and more employees in that sector that does not produce marketable goods or services than in the one that produces said goods and services.

The need to keep alive those activities that have constituted the pillars of our process, fundamentally education and health and free access to these services, is not discussed at all. On the contrary, it is about improving the allocation of resources and increasing the efficiency of their use by eliminating pockets of hidden and explicit inefficiency.

The very structure of state enterprises, where those dedicated to commerce predominate (between commerce, business and real estate services and restaurants and hotels, 40% of the 2,388 state enterprises existing in June 2023 are concentrated), demonstrates the need for that the reform to produce qualitative changes that should not delay much more.

But the reform, including the stabilization program, requires resources in monetary terms. Resource flows, internal and external, require a business environment that generates trust. Among the measures that could be evaluated, some require a specific sequence, a pre-established order, but some of them can also be executed in parallel.

Without attempting to outline any type of program, below I’m listing some of those that many Cuban economists have been recommending for more than ten years; measures that would generate confidence, improve the business environment and contribute to growth and macroeconomic stability:

- Negotiate and pay the debt (including dividends withheld from foreign investors) using, among others, national assets in different types of options.

- Facilitate businesses with foreign capital and national capital:

- Reduce approval times.

- Adopt the practice that prolonged silence in response automatically becomes approval of the business.

- Substantially reduce the “power” of ministries in the approval processes of new businesses between state and non-state enterprises, whether national or foreign.

- Allow local governments to approve businesses with foreign and national capital up to a certain amount, based on new regulations that guarantee their public nature and transparency.

- Promote the establishment in the country of investment funds and non-banking financial institutions and of a national agricultural and industrial development bank with national and foreign participation.

- Promote the creation of Special Development Zones in several provinces with the same tax and tariff advantages as those that the Mariel Special Development Zone has today, under the jurisdiction of the provincial governments and directly subordinated to the Council of State.

- Adopt as soon as possible an exchange rate regimen that restores confidence in the CUP and in the national banking system that facilitates, in the short term, the acquisition of essential inputs to increase the production and supply of food products.

- Further reduce the list of activities prohibited for the non-state sector.

- Allow the performance of professional activities as long as the provision, by suppliers, of those services in the public sector is guaranteed.

- Reintroduce the year of tax exemption for new ventures, whether MSMEs, cooperatives or local development projects.

- Eliminate the “orientation” of the limitation of the social objects of MSMEs.

- Grant local development projects the status of “legal entity.”

- Grant tax, tariff and exchange incentives to those enterprises (state, non-state and foreign) that are dedicated to food production, especially those that promote direct productive chains with the Cuban agricultural sector.

- Allow/encourage that international cooperation resources and associated projects can be developed under direct relations between the cooperative and private sectors without intermediation of state agricultural enterprises.

- Expropriate enterprises from the ministries.

- Subject the subsystem of state agricultural enterprises to a profound process of resizing their functions and size.

- Extend the time of the granting of land in usufruct and the legal guarantees for succession.

- Apply high and progressive penalties to those who maintain uncultivated lands

- Return a part of the ownership of the land to those who really work it, the small Cuban farmers.

- Encourage short supply chains and marketing of agricultural products.

- Merge ministries and reduce ministerial apparatus (assets and people) to what is strictly necessary and subject them to a strong budget restriction, which must be reviewed every year.

- Reduce the bureaucratic apparatus of the budgeted sector (assets and people)

- Radically change the allocation of investments that the State finances towards the sectors and enterprises (state and non-state) that produce food.

- Generate projects and programs (investment funds, for example) that make it possible to enhance the impact of at least a part of the remittances in the productive sector, in fundamental services (such as the care economy) and in the improvement of the housing fund of the country.3

- Accelerate the transition from the generalized food subsidy to the subsidy of people, with priority for pensioners4 without filial protection.

The lack of comprehensiveness, coherence, consistency and adequate sequencing have been repeated weaknesses of this reform/updating/modernization/transformation process that we have been in since 1993, or perhaps even a little before. It would be useful to learn from these last thirty years.

Saying what to do is much easier than finding out how to do it; it is an irrefutable truth. But waiting for everything to be “guaranteed” in a world full of uncertainties in the short and medium term does not seem like a good option.

It is true that we are in the worst of times; it is true that the siege that the U.S. administrations have cast is well cast; it is true that not all the resources needed, neither material nor human, exist; it is true that political sensitivity today is very high; it is true that some of what needs to be done has no proven guarantee that it will have all the success that is needed. The path is made moving forward, the poet once said.

It is also true that subordinating what needs to be done to the whims of the U.S. administrations does not seem like the best option. Refraining from doing what is needed for fear of the political cost will only increase that cost in the immediate future, even when the risk involved is high while success is not assured.

The inertia is worse. Conditioning the depth of the reform to sectoral or personal interests, using archaic and extemporaneous concepts to justify conservative attitudes that have led in a direction diametrically opposed to the prosperity that we all strive to achieve and that is a decisive component of the country vision.

It is possible, it has always been possible. Let’s start moving.

________________________________________

Notes:

1 Romero G.: “Coyuntura económica internacional y el sector externo en Cuba.” Presentation at the Annual Seminar of the Center for Studies on the Cuban Economy, Nov. 21 and 22, 2023.

2 Blanco H. “Una mirada al sistema empresarial estatal.” Annual Seminar of the Center for Studies on the Cuban Economy 2023. November 21 and 22, 2023.

3 “37% of the housing fund in fair or poor condition. Housing Plan started in 2019 with 12% compliance.” Odriozola S. “Panorama social, más allá de la coyuntura.” Annual Seminar of the Center for Studies on the Cuban Economy, November 21 and 22, 2023.

4 “44% of pensioners receive a minimum pension (1,528 CUP).” Odriozola S. “Panorama social, más allá de la coyuntura.” Annual Seminar of the Center for Studies on the Cuban Economy, November 21 and 22, 2023.

This is very nice! It gives me so much information about Cuba’s economy thank you. 🙂