I discovered steam locomotives at a very young age thanks to my friend Wildy, a photographer who loves these enormous machines. Wildy, in addition to helping me — along with many others — take my first steps in photography, introduced me to the subject of trains, about which he is passionate. As far as I know, he is even a meticulous model builder.

Since then, without becoming a fanatic or a scholar, in my wanderings through life, whenever I can, I photograph one of these enormous artifacts, extinct colossi like dinosaurs. Meeting a group of retired Germans, former railway workers, on a photography assignment some time ago and experiencing their passion for steam locomotives up close, helped me appreciate them a little more.

Thanks to the sensitivity of the late City Historian, Saint Eusebio of Havana, as I like to call him, at the beginning of the century it was decided to rescue steam locomotives throughout the country, mainly those belonging to sugar mills. Many of them, over 100 years old, continued to transport sugar cane during the milling season.

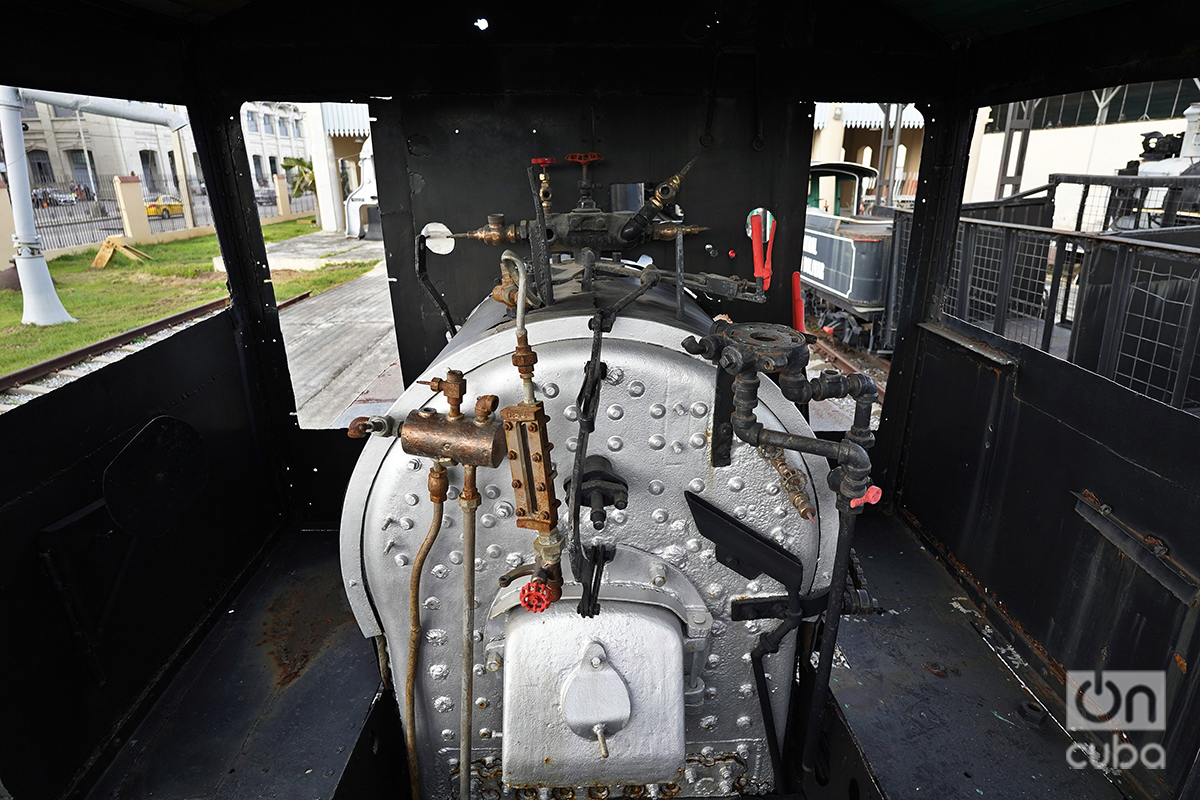

Today many of these machines are on display at Cuba’s Railway Museum. A few restored ones are on display inside the building, and most are out in the open, on rails and in the weeds, proudly displaying a sheet of rust, twisted metal, worm-eaten wood and leaky boilers. Traces of the many years that they were a vital part of the once powerful Cuban sugar industry.

Located in the former Cristina railway station, very close to the Cuatro Caminos Market in Havana, the Cuba’s Railway Museum was opened in 2000 to display surviving equipment from the golden age of trains and railways, from times when these machines were part of something so great that it gave rise to the phrase “without sugar there is no country.”

The jewel in the museum’s crown is, without a doubt, “La Junta de Fomento,” popularly known as “La Junta,” declared a National Monument in 1998. Built in 1842 in New Jersey, it is the oldest preserved locomotive in the country. As far back as 1843, it was already traveling through the Cuban countryside. Today, at 181 years old and out of service, it still has many of its original parts.

Cuba’s Railway Museum was restored in 2019 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the founding of Havana. The saving hand is evident. Inside the once neat and painted station, several recently restored locomotives are on display to the public, among which, as soon as you enter, “La Junta” stands out.

But the human absence is striking. I was there for more than two hours, during which only a guard who was dozing at the entrance, bored to death, and I were present. When I asked him, he told me that it was like that every day, that very few people came to the museum.

For me, the most valuable thing in the museum — and what I photographed the most — is in the courtyard, exposed to the fury of the elements. In this sort of train cemetery, most of the rescued heritage, not yet restored, is displayed. Gigantic steam locomotives that refuse to die and await the arrival of better times to rise like a Phoenix from rust and oblivion; old warriors that barely survive, without witnesses.