More than a week has passed since the Central Bank of Cuba (BCC) announced a group of actions to promote bankarization and the use of electronic channels on the island. As well as the publication of the controversial Resolution 111/2023 that, among other novelties, sets the maximum limit for cash operations of all economic actors, both state and private, at 5,000 CUP.

The new measures, established in the midst of skyrocketing inflation and a deep economic crisis in which the Cuban currency depreciates daily against the dollar and other currencies, have left no one indifferent. It has provoked endless opinions and questions.

While the BCC and the Cuban government defend the (“gradual”) implementation of bankarization as a necessary step and assure that it will benefit “the majority of the population,” economists, academics and businesspeople have warned of the negative effects of the measures on the Cuban economic framework.

Reduction in the supply of goods, greater depreciation of the Cuban peso, more informality in the monetary sector, contraction in the activity of the new economic actors and effects on state enterprises linked to the private sector, are some of the foreseeable consequences warned by them.

It would be necessary to add the impact that the above would have on Cubans, who since long before the new measures have been dealing with precariousness and uncertainty in the midst of the chronic crisis that the island is dragging. Crisis accentuated by the pandemic, U.S. sanctions, the war in Ukraine, and the failure of previous policies implemented by the government, which have had a direct impact on their pockets.

It is not surprising that, in line with what has been pointed out by experts or with their own reasons, many on the Cuban streets do not hide their concern and distrust of the recently announced package. And even without fully understanding the content and scope of the measures in their daily lives.

***

“Honestly, I don’t understand much about the matter,” confesses Ana María, a retiree who I meet in line at an ATM in Old Havana. “Enough with the fact that I learned to cash the checkbook around here. Even though in the end it’s not enough….”

For her, as for others who are waiting for their turn at the ATM, “electronic money sounds very nice; but leave me with the cash, with the hard cash. A bird in the hand is better than two in the bush…,” she affirms.

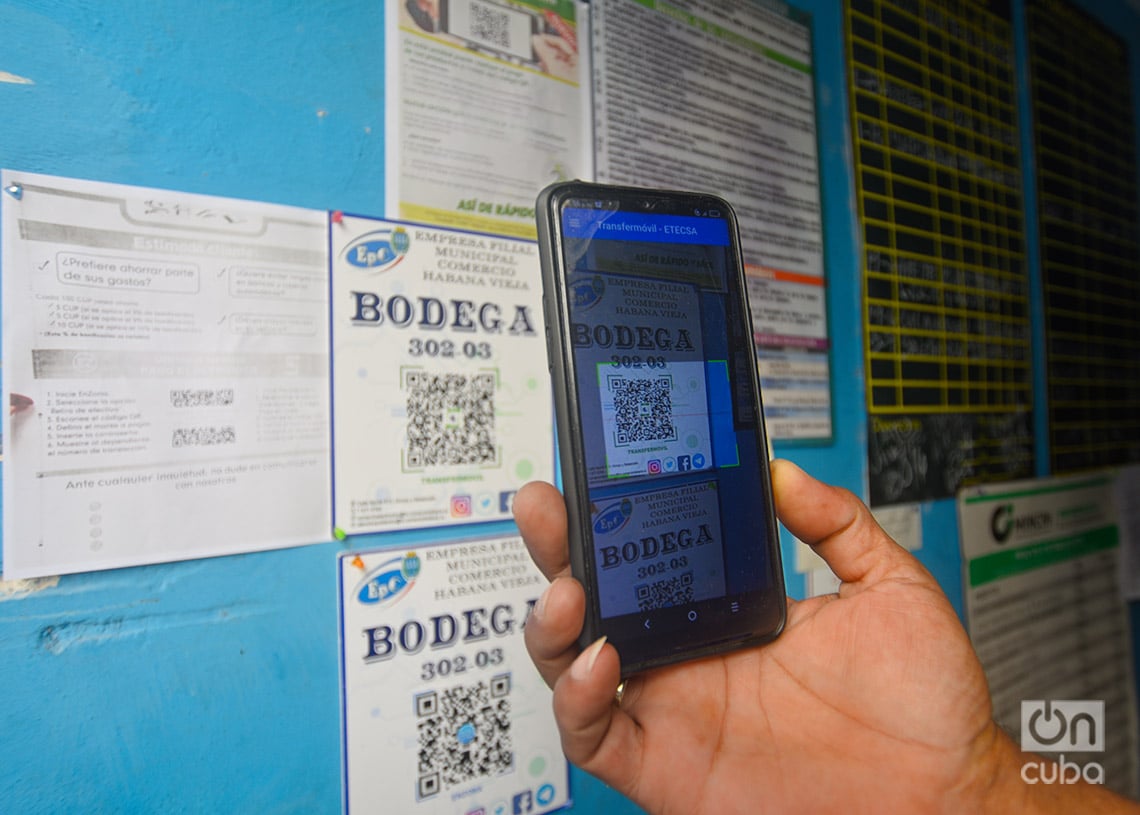

Rolando, a 53-year-old mechanic, agrees; although without ignoring “the advantages” of electronic payments. “I have been paying for electricity and other services by Transfermóvil for some time, and it is true that it is easier. But there are many other things that cannot be paid for out there, the same for avocados to a street vendor or a stretch on an almendrón. That, without talking about the black market, which is what many people use.”

“Right now,” he notes, “after the measures were announced, there are sellers who used to accept transfers and now are no longer doing so. It happened to me with one from whom I bought chicken and hash under the counter, and with a bread vendor. People want to have cash, so how am I going to charge my clients?”

Other repeated concerns on the streets are related to technology. Although the authorities have highlighted that in Cuba there are more than 7.6 million active mobile lines, of which some 6.7 access the Internet, while an electronic payment gateway such as Transfermóvil already has more than 4 million users, a not inconsiderable sector of society today does not have mobile devices or real connectivity.

Many are elderly people with low incomes, in a country where the low birth rate and constant emigration keep population aging on the rise while pushing down the number of working-age Cubans.

“My grandmother doesn’t have a cell phone and she doesn’t understand Transfermóvil or anything like that. I help her with some payments through my cell phone, but there are many older people who have no one. If now they begin to eliminate cash payments, as it was said they were going to do in some places with the electricity bill, or if the problems continue to withdraw money from ATMs and banks, what are these people going to do?” reflects Alejandro.

The 25-year-old young man, a medical graduate, points to another collective concern: the daily technical and connectivity difficulties.

“How are they going to want to do that in Cuba, when any old thing makes the connection not work and you can’t make a payment, or you do it and then it does not appear registered and they want to charge you again, or applications such as the one to buy tickets freeze in the middle of the process?” he says.

“Or that the POS in the stores have no connection and you have to leave without being able to buy or wait for nobody knows how long, as it happened to me. And furthermore, they are stores in freely convertible currency,” Mariana, his girlfriend, who studies at the university, supports him. “As long as those things are not fixed, they should not take a step like this, I think.”

***

The morning progresses and many Havana banks show a similar picture: numerous people waiting to be able to enter to carry out the procedures and operations they want or need to carry out. Queues are also the usual scene at ATMs, where they do work.

Although days have passed since the new provisions for bankarization came into force, the outlook does not seem to be very different from what existed before the announcement. At least not yet. The president of the Central Bank himself acknowledged that, based on what was reported, an increase in operations in branches was expected; but he assured that organizational measures would be taken to organize banking work.

In this sense, in a symptomatic decision, some banks began to work on Sundays to “facilitate” the availability of cash to their customers. The start of a training program for workers in the sector, the population and different economic actors were also reported, to “achieve general awareness about bankarization” and clarify doubts.

In addition, the president of the BCC confirmed that the limit of 5,000 pesos per operation, established in Resolution 111/2023, “does not apply to individuals”; but he clarified that “you have to see the capacities of each branch.” And those capacities, in not a few places, are diminished by the cash deficit.

The deficit, undoubtedly a catalyst for the new measures, had already been generating — along with endless queues — growing discontent and criticism among the population. And still continues to generate them. In the banks, some Havanans tell me, they only allow you to withdraw up to 2,000 pesos, if they have money. Or one customer must wait for another to make a deposit before they can withdraw that same cash. And in the ATMs there are often only low denomination bills.

“At the moment, I don’t see any change. I even think there are more queues at the banks. And at ATMs things are more or less the same,” says Camilo, a 37-year-old computer scientist. “I know that a short time has passed since they announced the bankarization, but I don’t have much hope of improvement,” he adds skeptically.

“Banks in this country have been working poorly for some time, like so many other things. And, until now, the government has not hit the nail on the head with any new measure. If anything, it’s been for the worse,” he reasons. “Look at what happened with the Reorganization, which rather came to disorganize things even more. Or with measures to boost agriculture. Why is it going to be different this time?”

“Do you know about Murphy’s Law, journalist?” Javier asks me, introducing himself as a musician, artisan and cultural promoter. “Well, the government seems not to,” he answers himself. “If something can go wrong, it will go wrong,” he recites it from memory. “And it seems to me that this measure can backfire again.”

“I sincerely hope I’m wrong, but just reading what various economists have said, with clarity and arguments, the matter does not look good,” explains the young man. “What I don’t understand is how those who take these measures don’t realize these things; how they don’t anticipate the consequences before deciding something like that, and, furthermore, they hope that nobody criticizes them.”

***

Along with concerns and questions, caution and expectation are perceived in the streets. Not a few prefer not to talk about the subject “just in case” or argue that they still don’t understand enough to give an opinion. Others bet on giving “a margin” to bankarization and granting the government an umpteenth vote of confidence, at least for the moment.

“You have to give it some time to see if things are rearranging themselves,” considers Ofelia, 48, a lawyer by profession. “Perhaps this was not the best time to do something like this, due to the crisis and other situations that should have been seen first; but the reality is that there are serious problems with cash and the government had to do something. Now you have to give it a margin of time,” she insists.

For his part, Felipe, retired from the Ministry of Industry, confirms that he also prefers to collect and pay in cash, but that “you have to understand that times change. Cuba has to adapt to how things are today in the world, and do what we can with the little we have, because the country is not going to stop either, is it?”

“What happens,” he points out, “is that there are people complaining because there is going to be greater bank control over cash and many things are going to have to be done electronically. But, if an enterprise or an individual cannot, or does not want to operate under these conditions, it has to be called to chapter. Maybe he’s been doing something he shouldn’t and now he’s going to have to go straight.”

Camilo, on the other hand, is less optimistic: “They can try to control whatever they want, but the one with the money will not let go and the most affected, once again, will be the people. I don’t know how they don’t realize that. There are already people charging for giving cash in exchange for transfers and also inventing a thousand other complications. And look at where the exchange rates for the dollar and the euro are, which have already broken Sotomayor’s record.”

“For me, it’s convenient that the dollar rises, because that way I get more money from what my family sends me,” says Dunia, a 45-year-old laboratory technician. “But, on the other hand, if the prices of everything else also go up, it’s not like I’m going to gain much either. As things are, money disappears like a magic trick and let’s not talk about wages. What is clear to me is that, just in case, I want the dollars that they pay me in cash.”

“Those who buy and sell currencies will continue to do so, and move cash out of banks. And the dollar and the euro are going to continue to go up because they are needed to buy outside of Cuba and what the government sells is nothing more than a trickle,” reflects Javier, who regrets that the authorities have not said “not even a word.”

“And prices must go up,” he concludes, “because if SMEs can’t buy a lot of dollars, neither legally nor illegally, they won’t be able to import much either. That is elementary. Unless the government goes crazy and starts selling them wholesale dollars; but I don’t think it’s going to happen, because it doesn’t have that kind of money for that. If it had enough dollars, we wouldn’t be where we are. But it seems that there are no Cuban pesos anymore…”

Eric is completelly right . as are most of the people , this is an attempt to control cash . then the actual value of the peso no longer matters .. Bert

Sounds like Cuba needs more intelligent leadership.