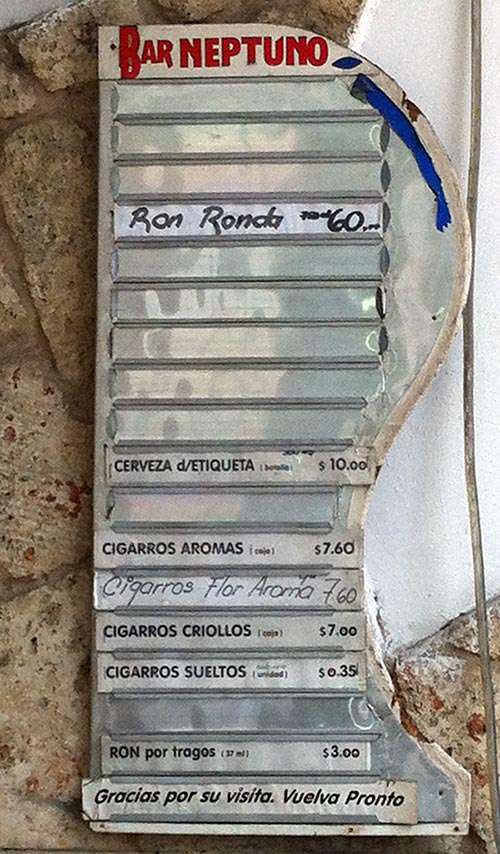

Whoever invented the phrase probably went through a state cafes on Neptuno Street, perhaps by the Neptuno Bar in Central Havana, on the corner of Marqués Gonzalez and, after looking at the dumpy tablet which also read Ronda Rum, Aromas and Criollos cigarettes, said: “Give me a croquette and bread”, and paid one peso and fifty cents.

A few minutes after buying it I ate it, at the risk of what could happen. The stomach of Cubans born with the Special Period is tough, I thought. And to know how it was I had to try it.

The taste of a croquette (and its cousins, the fried one, hamburger and others) of a State café in Neptuno Street is semiacid. Unable to determine if they have this flavor since fried, or acquire it after they have spent eight hours in an uncovered box, less than two feet from the street, gathering dust, saliva from the clerks, and getting stiff to the smoke old cars let loose by the exhaust, when they are going on Neptuno.

The bread that came with the croquette in a state cafeteria can sometimes have small black dots in the form of freckles. The flavor is not as acidic as the coquette itself, but is not far behind.

The ingredients of these fried foods are still a mystery. None of the interviewed clerks in the more than 10 state cafes in Neptuno makes the croquettes they are selling. For the twentieth century cafe, on the corner of Belascoain, one of the clerks responds like this the following questions:

– What are the croquettes made of?

– Chicken.

– Do you make them? How?

– No. I do not know about that. The manager takes them out already made and we fry them, and sell them.

– And how do you know that are made of chicken?

– He says they are chicken.

In state dining establishments of Neptuno there is something common, besides flies, dirty counters and clerks that clean the sweat with the back of their hands and then give you the croquette with that same hand: No clerk or manager of a state cafeteria in Neptuno likes their picture taken in their premise.

The manager of the Neptuno Bar says sometimes they prohibit photographs because many journalists wanted to do “bad things” with the pictures later.

– What’s here that you do not want to be seen in the press? I wonder.

– Nothing, nothing, he responds.

Ultimately, neither the manager nor the clerks should primarily feel responsible for the state of their business, since it is not in the hands of any of them to change these conditions. Then, as the fault is not theirs, none of their acid croquettes or hambergue and breads will be on the cover of the national media.

The culture of ordinary croquette and acidic breads is not new in Cuban gastronomy. Back in the 70s, the Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas described the famous “croquettes from heaven” in the cafeterias of the State, that stuck to the roof of the mouth and you could swallow them only after unstuck them with your fingers.

However, in Neptuno, crowded street with many fruit stalls, vendors, state and private dining and small markets with sales in CUC also arise new forms of gastronomy now under the Self-Employment modality. The differences are enormous, as you can see just looking at the pictures of the menues, for example, the Neptuno Bar (state) and private business Pa’ Comer.

It would be good to see these new businesses move out slowly the dirty state business in which menus offers with bad hygiene and vulgar service little more than rum, cigarettes and beer.