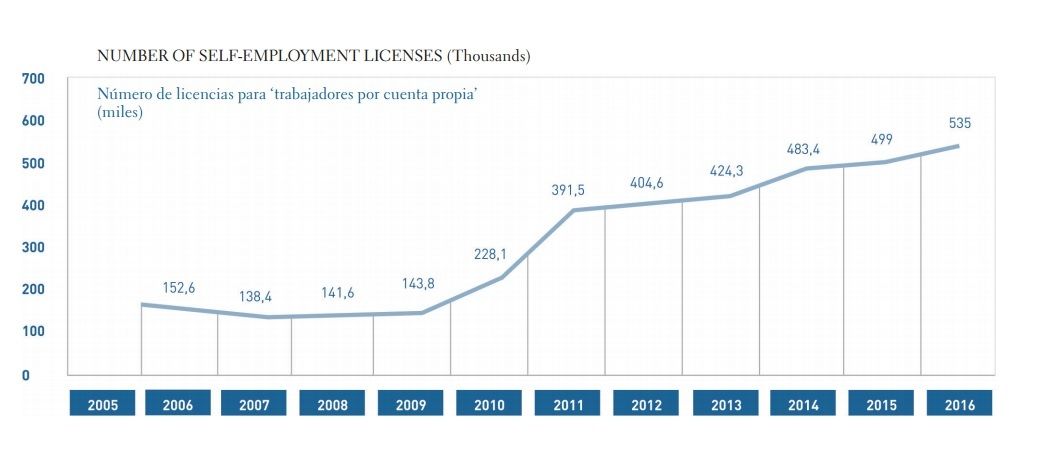

In spite of everything, the expansion of micro and small private enterprises in Cuba has been sustained. In 2010, the year in which the government started giving new licenses for private activities and introduced some flexibility in the markets, the number of businesses grew by 59 percent. In 2011 the increase was even bigger and reached 72 percent. Starting 2012 there was a cooling when the sector approached the potential levels and when they faced a lack of other complementary policies.

Despite the Cuban private sector’s difficulties to have legal access to supplies and the capital it needs, and the extremely restrictive regulatory framework in which they operate, the micro and small enterprises have continued generating employment since 2012 to a rate of 6.4 percent each year, on average. Last year, even with the recession and the financial crisis on the macroeconomic level, the amount of private jobs registered a 7.2 percent increase.

For the time being, the Cuban private sector is mainly concentrated in the microenterprise (the average number of workers per enterprise is around four), although there are some cases in which it is higher, but without even getting to be a medium enterprise.

The private sector, together with the cooperatives, is important for a growing number of families as a source of alternative incomes for the depressed state wages; it provides around 30 percent of the economy’s total employment, helps the competitiveness of the tourist sector and is key to food production. Furthermore, it has been the cornerstone in the official strategy that seeks to reduce the size of the state without affecting the added unemployment figures. Therefore, its sustained growth and resilience is very good news.

However, the news could be better if at some time the Cuban government would change the space it conceives for the private sector in the country’s growth and development model. In fact, a more demanding view of data on the private sector would lead to the conclusion that its recent expansion has occurred to the detriment of economic efficiency.

The weight of the added value of the private and national cooperative sector (adding self-employed workers, cooperatives and farmers) barely moves between 6 percent and 9 percent of the total GDP (remember that it employs 30 percent of the workforce). When the dynamics of the Cuban economy’s productivity (Total Productivity of the Factors) is estimated one can see that it increased between 1996 and 2007 at an average annual rate of 3.5 percent, while between 2008 and 2014, coinciding with the private sector’s greatest expansion, the increase in productivity dropped to 1.1 percent.

Two factors could be identified behind these numbers. The first has to do with the example of the engineer or the doctor we find driving a taxi or waiting in paladares, an example multiplied dozens of thousands of times, and extrapolated to other university professions and workers with an accumulated labor experience, to which they resign to be able to get a minimum of incomes with which to maintain the family. It makes no sense that the country has invested millions of dollars in education for decades and now designs a policy that only guides and limits the private sector towards activities that generally have a very low added value and scarce technological intensity.

Informality predominates in Latin America’s small-scale private sector and it generates many more jobs than added value. But Cuba should do everything in its power for this to not happen. Social conditions and human capital training exist that offer options for this to be different.

The second factor, and not alien to the first, has to do with the topmost policy of “avoiding the concentration of wealth.” This is applied to such a point that all businesses earning more than 2,000 dollars a year are charged a 50 percent tax rate. No matter how you compare it, it is an excessively high rate that does not agree with the international tendency of supporting and promoting the small and medium enterprise, and above all it is an incentive for tax evasion and informality. In this same bag we can put the tax rate in force that increases to the extent that the enterprise generates more employment, and the regulation that limits to only one establishment allowed per each license granted to operate a business.

International experiences increasingly show that the new enterprises, the enterprising spirit, and the growth of small and medium enterprises are a transcendental means for the introduction of innovative ideas and of high productivity in the economies. But for the increase in productivity to be seen on a large scale and for it to contribute to the GDP growth it is indispensable that the innovative enterprises can increase their size so that, through a competitive process of self-selection, the ones with the highest productivity absorb the production factors (capital and work) previously used in less productive activities.

The regulatory and tax framework, and the political rhetoric, should not punish and discourage the growth of the private enterprises that gain in competitiveness and market spaces based on innovation. For the contribution of the private sector to the GDP to be significant, the Cuban government would have to bring down that threshold that restricts the activities of low added value to the private sector and keeps the rest of the economy only for the state enterprises and joint ventures or 100 percent foreign investment enterprises. The government would have to think out productive development policies that integrate all the enterprises, independently of the form of ownership, in order to take advantage of the quality of the available human capital.

In addition to an adequate regulatory and tax framework, the economic policy must guarantee access to financing, something that is complicated if it is to come only from bank credits, given that in many cases it would involve new projects and without tangible collaterals. An option that can be explored to connect the Cuban small and medium enterprise to foreign financing is the risk capital funds. These funds tend to accept innovative ideas as “collateral,” since as a counterpart they demand a future participation in the enterprises’ profits.

For example, the Computer Science University (UCI) has made an important investment in recent years in the formation of capacities in the informatics field, capacities that today are not exploited to their potential maximum. The organization of the private sector in small and medium enterprises geared at the production of software, programming and other related activities, with risk capital funds, could be an option to assess. The self-employed workers, which today operate under the figure of license for “programmer of computer equipment,” could be the embryo for this takeoff.

In the face of the Venezuelan crisis and the recession in which the Cuban economy has fallen since 2016, the Cuban authorities seem to only want to bet on large foreign investment projects, obviating that these large projects do not operate in the void, but rather, to be competitive and financially and operationally viable, they need a dynamic small and medium enterprise sector to which they can interconnect.

The next Cuban government should stop measuring its strength according to the number of state enterprises and to how much monopolistic control it has over the markets. It would be stronger if it were to rest on a vibrant economy, favored by a regulatory framework that promotes competition, entrepreneurial growth and innovation, and thus register greater fiscal incomes through a truly progressive tax system, with which to be able to sustain the universal access to education, public health and a quality social assistance system.