In February of 2015, when the store and design studio Clandestina opened its doors a few blocks from the Capitolio, Idania del Río and Leire Fernández had set out to create a design boutique right in the middle of Old Havana, with San Sebastian, New York and Paris as references.

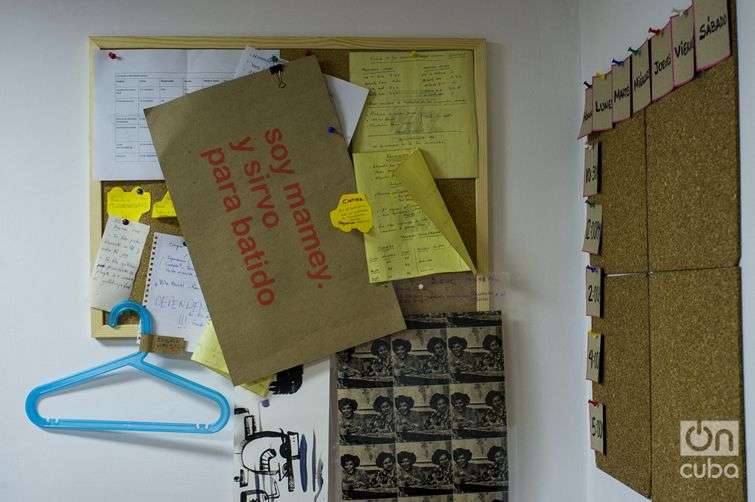

Amid décor that includes pop-art hearts and nods to the unavoidable tradition of revolutionary poster-making, with the epic slogan “On to the sugar cane harvest,” a certain minimalist halo immediately distinguishes this place from the conventional labels framing more popular businesses that spring up all over the city on a daily basis.

It’s not an art gallery or a paladar (private restaurant). These two young women have found a way to prosper in a different enterprise, one that is economically sustainable, and with the fearlessness needed to open up a path of creative flexibility for designers whose desire is to offer a different image of Cuba today. Beyond the recurrent souvenirs that dominate the market and legitimize symbols of identity, their concern is for customers to find a certain touch of sophistication, which is often missing in national products.

The birth of a brand

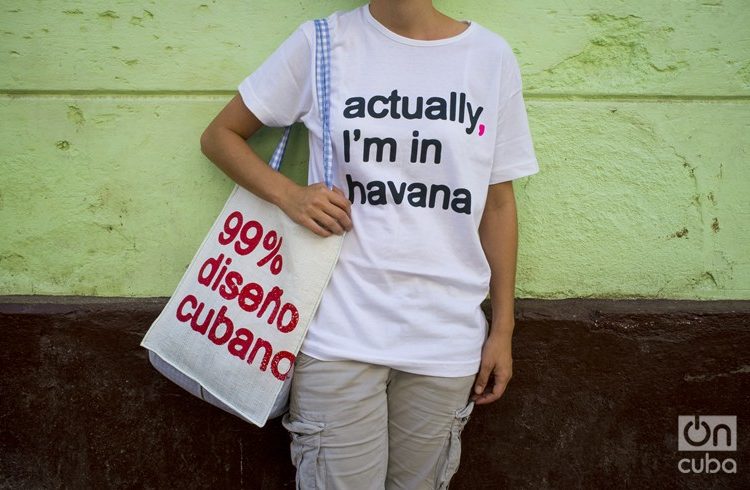

A declaration of principles identifies the T-shirts and purses sold by Clandestina: “99{bb302c39ef77509544c7d3ea992cb94710211e0fa5985a4a3940706d9b0380de} Cuban design.” They started out with tank tops and posters by Del Río, which have attracted attention overseas, leading them to exhibit their work in the United States, Europe and Asia.

Then they incorporated other garments: drinking glasses, pillowcases, hats, toys and items made-to-order. Their most ambitious project to date is making and establishing a Cuban clothing brand, Clandestina and Vintrashe.

“What we offer is a discourse,” says Leire Fernández. “We’re interested in making a totally consumable product, for both local customers and visitors. And we would like for anyone from a reggaeton musician to an office worker to dress in our clothes.”

A very discernable philosophy marks every piece in this store/studio, the idea that the value of their products does not lie merely in the final result, appearance or utility, but also in the daring and inventiveness involved in the whole process of their production. There is little or no similarity between the routines of production here and the artificial and mechanical processes of a capitalist megafactory, or its opposite, a Cuban state enterprise.

Certainly, the recycling of a tank top that is turned into a Vintrashe miniskirt has different meanings for a Cuban and for those who are passing through the city and visit the store. And these young women entrepreneurs admit that it’s the sort of originality that Europeans love.

Ingredients for success

Designers are said to belong to a race of humans who spend their lives trying to understand the grace of how and why certain objects look better than others. But, how to transcend that mental and material state of being resulting from a context where a utilitarian sense, necessity, and a shortage of raw materials constrain the elegance of form?

This first year, Del Río and Fernández have contributed lessons that perhaps they were able to understand only from the whole of the creative process itself: it is only possible to be successful in a business here when it flows in the same logic of ideas and production used by Cubans to “resolve” things in their lives.

Every obstacle is met with a more criolla (native-born) solution, and the most unexpected situation is met with playfulness. When it is almost impossible to import cotton, at Clandestina, they opt to recycle garments from used clothing stores, or transform the ones that customers are wearing for a reasonable price. If there aren’t many potatoes on the market, they find some, color them, and put them for sale in a shop window. And last August, when U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry visited Havana for the opening of the U.S. Embassy, they made a series of commemorative “Welcome Kerry” fans.

There is a well-known principle that a designer’s ingenuity is measured by his or her capacity for dealing with change, for bringing about the metamorphosis of something ordinary into an ordinary object. Idania del Río, a 2004 graduate of Cuba’s Institute of Design, ISDI, sums up the philosophy that has guided her project to success: “In Cuba, that’s how things are, and we love doing it this way.”