In search of the source of fortune, feeling like a new tropical conqueror, Oscar Paglieri burst into Havana when one world — the 19th century — was dying out and another — the 20th — was dawning. As soon as he set foot in the city, he was enveloped by a secret feeling of predestiny and as an enterprising and stubborn Italian, he set to work to forge the dream that he had pursued for years: to have his own jewelry and precious metal engraving workshop.

Flirting with his horizon, the Turin native christened the brand-new business La Estrella de Italia. The assumption of the name confirms that despite the Cuban hospitality he had not taken his homeland out of the trunk of memories. From southern Campania, the hills of Tuscany to the coastal landscapes of Liguria and Piedmont, the Paglieri surname is rooted deep in the cultural and regional identity of Italy.

Immersed in his atelier, Paglieri spent hours and hours of pirouettes with tweezers and magnifying glasses developing his inventiveness, his precise pulse to carve surprises and, above all, his dazzling technique. He was seduced by molding gold, silver, precious stones…melting them, amalgamating them, playing with them; aware that they were pieces that couldn’t be resisted by most mortals.

His venture could have been one more lost among the thousand stories that marked the waves of migration from Europe to America, entire generations crossing the ocean in search of a better future. But the story of Paglieri is so immense and little known that it certainly deserves to be told. Today we could consider him one of the fathers of contemporary goldsmithing in Cuba, where the Italian influence — after the Spanish — is a decisive ingredient in what Don Fernando Ortiz called the Cuban “melting pot.”

Born under a lucky star

Officially registered as a silversmith, jewelry and diamond workshop, La Estrella de Italia quickly became a favorite subject of popular gossip, and the name of its founder began to spread as a brand of talent and exclusivity. Private commissions began to pour in from the nobility seeking to satisfy ornamental whims, and the modest house began to gain in competitiveness to compete with La Acacia and Cuervos y Sobrinos, two of the old and accredited entities in the field.

There is documentary evidence that around 1895 the establishment was located at number 107 Calzada de Monte, which for some time was a busy commercial artery due to the line-up of shops, hardware stores, inns and businesses of all kinds with eye-catching signs, decorations and an abundance of offers.

As the Republic progressed, the Havana aristocracy strengthened its obsession with noble attire and jewelry in the best court style, to the point of not giving a reprieve to their clothes, even to fan themselves in the palatial portal on Sundays. By then the industrious Paglieri had already decided to take his business to the next level with industrial-scale production. He formed a team of craftsmen who knew how to make everything, from cufflinks and earrings to the largest and most complex orders. Beyond the usefulness of the machines, for him the skill and artistic sensitivity of his employees were the most important thing.

Thanks to his growing reputation and economic boom, in 1899 he moved La Estrella de Italia to a more suitable space at 46 and 48 Compostela, between Obispo and Obrapía, the heart of Old Havana. It was impossible not to stop in front of the window, splendid and shiny like a silver cup, to praise the beauty of the display. Similar to the admirably linked chains they had on display, each client recommended to their friends the place where they could buy a special gift. Paglieri went from being a simple jewelry seller to a master jeweler, a reference figure. His pioneering manufacture grew more and more and diversified until it became an empire.

On good authority

The Italian’s genius was not only noticed by important people, but reports soon appeared in the newspapers. The Diario de La Marina, for example, went so far as to call him “Benvenuto Cellini of the modern era,” and estimated that, to the honor of Cuba, Paglieri’s house was in a position to compete with the most distinguished foreign jewelry stores.

In its evening edition of September 30, 1903, the aforementioned newspaper invited readers to admire all kinds of notable works in the Compostela workshop, among which two pectorals and two episcopal rings covered with gold and emeralds stood out, “a wonder of art and good taste” — according to the chronicler — destined for the new bishops of Havana and Pinar del Río, Monsignor González Estrada and Monsignor Braulio Orúe, respectively.

“A round of applause, not to the artist who has produced these and many other works of merit and value — such as the solid silver dog, commissioned by a devotee for a miracle, which is displayed in the window case itself — but to the city that has it in its midst and that has nothing to envy of the most advanced in art in what concerns the silverware branch,” the text emphasized.

The same, although in its style, was opined by El Fígaro on March 14, 1909: “It can be said, because it is true, that every work of art executed today in Havana, and even in the interior of the Republic, that has any importance, is unfailingly entrusted to La Estrella de Italia. And so it has to be, since no other house can offer better guarantees of perfect execution and serious compliance than the great Pagliery jewelry store.”

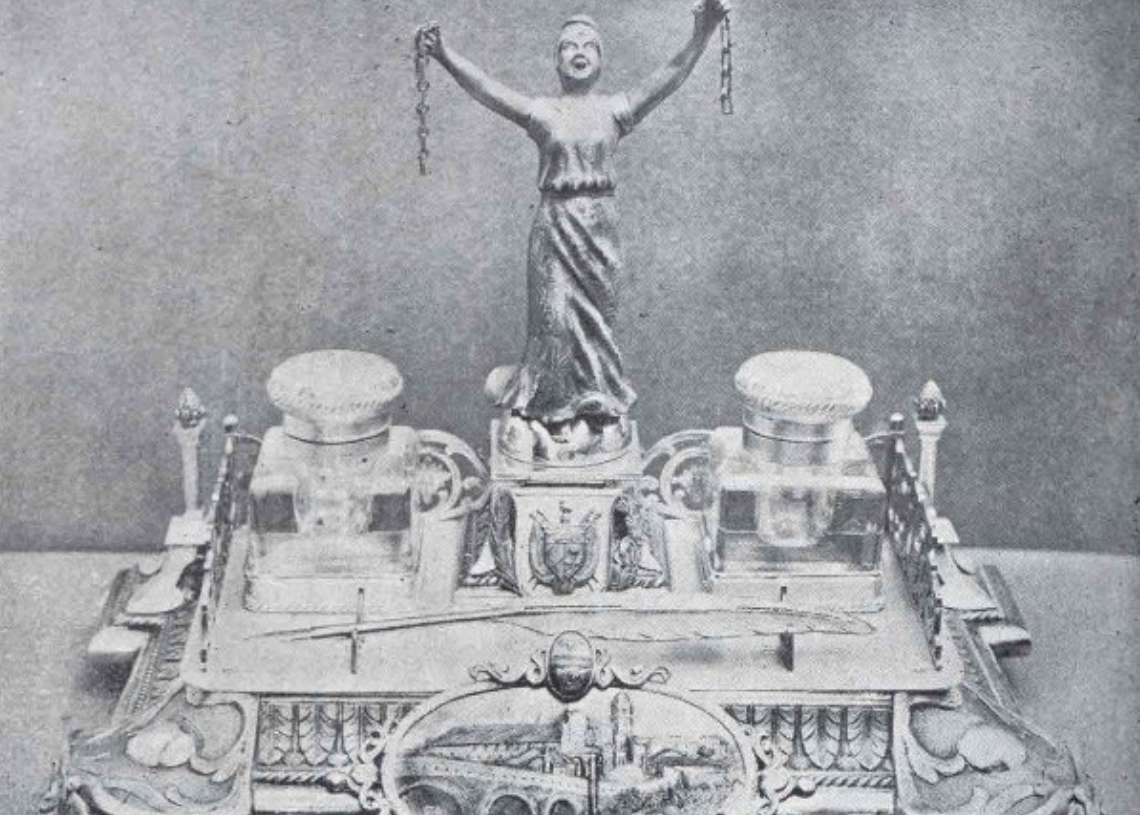

A couple of years later, the magazine Bohemia dedicated on March 19, 1911 two pages to celebrating the company’s recent triumph, having won the Grand Prize in the Arts Section of the National Exhibition, held at the Quinta de los Molinos. A wonderfully executed silver shield of Cuba; the “Almendares” Cup that the magnate Eugenio Jiménez, tenant of Almendares Park, used to give to the champion baseball team; a silver portrait of Miss Carmelina Guzmán; as well as a collection of enameled carvings and dreamlike filigrees made up the jewelry stand inside the pavilion, captivating the public and winning the jury’s reward.

“With intense and proper brilliance, La Estrella de Italia has shone in the firmament of the National Exhibition, standing out with unusual brilliance among those of all magnitudes that have illuminated the contest. The name of Oscar Paglieri is so closely linked to that of La Estrella de Italia that they are often confused when talking about work in jewelry and fine metals in which the chisel plays a major role. Mr Paglieri is a consummate artist; an exquisite architect; an enterprising, cultured and modern spirit,” the article said.

Constellation of works

His pieces were inspired by the most diverse lines and the most exotic models. Crowns, necklaces, charms, statuettes, miniatures, watches, medals, album cover plates, trophies or plaques to place at the foot of sculptures — the list would be endless — were scattered around the rooms of high-class ladies, artists’ dressing rooms, executive offices, sports clubs, institutional headquarters and museums…in short, the work of the notable engraver was linked to everything that signified progress.

To give you an idea: the medal presented to General Máximo Gómez on May 20, 1902 came from La Estrella de Italia. Commissioned by a group of chiefs and officers who fought under his command, the 18-carat gold piece, weighing approximately three ounces, with a pin and case, had the profile of La Cabaña Fortress engraved on the front and an inscription dedicated to the Generalissimo. “We owe the realization of our ideal to his genius and perseverance,” it said. The reverse featured the National Coat of Arms, the date and the dedication of the comrades in arms. It is currently part of the collection of the Numismatic Museum.

Meanwhile, the Goldsmith Museum has a commemorative piece in its collection consisting of a gilded silver lion lying on a handful of coins melted by the explosion of the battleship Vizcaya. It has an irregular-looking silver base with bulging legs. The details of the anchor, war objects, ivory, rope and lifebuoy refer to the ill-fated ship of Cervera’s fleet that was sunk in the naval battle off the coast of Santiago in July 1898.

Other memorable pieces were a silver emblem by Eusebio Hernández — a doctor and friend of Antonio Maceo — that symbolized an open scroll with the woman Cuba and a fragment of the doctor’s patriotic letter renouncing his leadership of the Liberal Party and his candidacy for the national government. Likewise, the Coat of Arms of Cuba, all in silver, which adorned the office of President José Miguel Gómez, or the “Habana” Cup, with allegorical ornaments of gold and silver and colored enamel, which was presented by the capital’s City Council as a trophy during the first international automobile race held in Cuba, on February 13, 1905.

But without a doubt the most iconic work for its significance in the nation’s historical, devotional and cultural heritage of those made in La Estrella de Italia was the trousseau that displays the representation of Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre, Cuba’s patron saint, and which was placed there by the delegation of Pope Pius XI in 1936. The crown displays the coat of arms of Cuba on its sides, the Royal Palm in the center and at the base the motto “Ambulavit Mater,” which alludes to the “Mother of Charity who walked on water”; while the halo recreates the sun with its 12 stars and the inscription Ave Maria. Both pieces are made of 18-carat gold and platinum with 1,450 diamonds, rubies, emeralds, pearls, among other precious stones set. The crown of Baby Jesus is also made of gold and platinum, adorned with pearls and diamonds.

Cuba for Italy

Even though he made some of the most expensive or exclusive pieces on the market and rubbed shoulders with the celebrities of the moment, Paglieri never went crazy with superego or cut ties with his country.

A member of the Mediterranean community settled in Havana, in early 1909 he was unanimously elected ― surely due to his efficient and kind spirit ― as president of the Por Sicily and Calabria Italian Committee, created after the earthquake that devastated southern Italy at around five in the morning on December 28, 1908, causing 100,000 deaths; one of the greatest catastrophes that the continent remembers.

As part of this, he put his home at the mercy of the aforementioned committee and, to raise funds, organized an evening in which artists from the Payret, Nacional, Actualidades and Alhambra theaters performed various productions and excerpts from Puccini’s La Boheme and Verdi’s La Traviata. By the time Paglieri concluded his humanitarian mission on April 24, the committee under his auspices had managed to send 43,560 francs to Rome for the survivors of the earthquake, a sum that was not inconsiderable at the time.

He was also among the founders of the Italian Patriotic Society, established on February 1, 1912 by Italians living in Havana for patriotic, unitary and recreational purposes. The Italian minister on the island, Giacomo Mondello, was the honorary president; engineer Stefano Calcavechia was the president and Paglieri was the vice president.

Not all that glitters is gold

Despite his aura and position, he suddenly fell into disgrace. Oscar Paglieri Galleani died in the Cuban capital on December 13, 1912.

A passenger list of the transatlantic liner America places him two months earlier, returning from Turin by sea route Genoa–New York–Havana. He was accompanied by his wife Virginia Paglieri, ten years younger. Had he gone to say goodbye to his beloved land or to recover his energy from the illness that, hidden away, was devouring her entrails?

His body was taken the next morning to Colón Cemetery in a procession led by representatives of the Italian community, Havana commerce and close friends. Paglieri was much loved by his compatriots and Cubans not only for his business prestige as manager of La Estrella de Italia, but also for being considered a champion of goldsmithing and a man of benevolent character.

“Mr. Paglieri was buried in vault number 861 of the administration acquired by Mario Ferrari and exhumed on December 20, 1922, to have his remains transferred to the ossuary owned by Evaristo Iduarte, located in the northeast quarter, block 23 of the common field,” the attentive historian Ricardo Díaz Murgas, a member of the necropolis’ museology team, told OnCuba.

Dr. Enrique Núñez diagnosed stomach cancer when he signed the death certificate in black letters. Although the causes may be multifactorial, modern medical studies suggest that gastric neoplasia would be more likely in people with occupations such as coal, rubber and metal. In this case, the jeweler Oscar had everything to lose. Did the same profession that brought him glory take him to the grave at the age of 49? Perhaps we will never know.

The story of Paglieri, the anointed one of La Estrella de Italia, did not have a happy ending; but it left a lesson on how determination leads to triumph even beyond death.