When, at the beginning of the 1990s, the US dollar was de-penalized and the Cuban government found its salvation in tourism, few could have imagined that a whole series of informal markets would develop around the inflow of foreign visitors.

The most notable impact of this phenomenon can be seen in Havana, Varadero and Matanzas, though all Cuban provinces – to a greater or lesser extent – have a tourist infrastructure that brings in revenues for the country and for private service providers. No few people have learned to “adapt” to this reality and make some money from visitors, offering transportation, a carwash, fruits, vegetables and other edibles, antiques, entertainment and many other services.

Santa Clara, for instance, is not the tourist destination par excellence. Here, privately operated hostels and restaurants take the lead in a context where State options are few and far between, generating sources of parallel employment as a result of their own, inherent limitations.

Emilia has been running a hostel in the downtown area for 3 years and depends on a minimum of four other people, those who buy the food and supplies for her business and satisfy the “whims” of the guests. From what she tells us, these “whims” can be anything from under-the-table tobacco, other smokeable products and, of course, “entertainment.”

“The next-door neighbors look after the cars at night. If they don’t, they get their tires burst before dawn,” Emilia sarcastically explains. “Another friend washes the cars, so they’re clean in the morning, and that’s all on the house.”

When one inquires about the best lodging options, the most frequent suggestion is to head over to Maritza’s, a 60-year-old woman who is always on the lookout for new tourists. “I help them, see. Because they’re not from here and they don’t know where anything is, where to stay or eat.”

The woman has a very humble appearance to her, even though she claims to make a minimum of 10 CUC (11 USD) a day through the commissions she receives by taking tourists to hostels and restaurants. On some occasions, tourists have invited her to dine with them. In those cases, she has asked for them to take the food to her in a doggy bag, as the restaurant owners aren’t too pleased with such invitations. “It’s not a part of the contract,” they explain.

“How do you manage to communicate with them?” I ask her. “It’s not that difficult. I make gestures and everything else is “good morning, my friend!””

The number of visitors hoping to get to know the socio-cultural peculiarities of the island and understand – if that’s possible – this outlandish bastion of tropical socialism, is increasing.

On Cuba Street, a stone’s throw away from where Maritza works, we run into Pierre at a lineup of people in front of a pizza parlor. This “friend” is a Quebecois who isn’t afraid of the heat. He walks around in shorts and thongs, dances with the first person to ask him and talks with everyone, including me.

“Doesn’t that bother you?” I ask him, pointing out the street corner where the Money Exchange is located and where we left Maritza and her zealous rivals behind. “No, it’s nothing like what happens at El Cobre, in Santiago de Cuba, or Trinidad,” he replies. “Things get really uncomfortable there, people even tug at your clothes.” Handling the hot pizza as best he can, he tells me that there are far more many beggars in other countries.

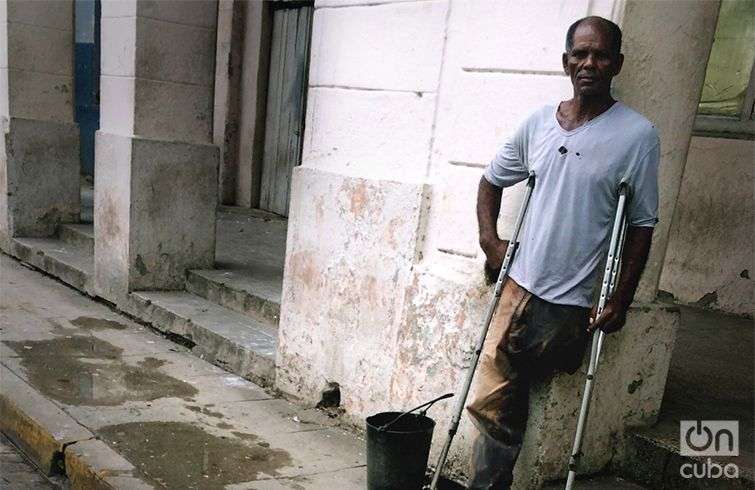

Many of the people who stalk tourists in Cuba, however, are not beggars, as Pierre seems to believe. There are those who are a bit more dispossessed, like Roberto, who lost his left leg and doesn’t work as a car washer for any hostel or business. He waits for a car to arrive and offers this service to the driver. He knows some people say yes out of pity, but he doesn’t care. His is an honest job and it puts food on his table.

At the entrance of the Santa Clara Libre Hotel we run into Muñeco, a kind of entertainer who is very popular in town, who assures us he is not a “music whore,” that he will sing to anyone, both Cubans and music-loving tourists like Pierre. “I don’t ask for anything. If they give me something, I thank them with another song,” he says.

Others, like Juanito, look for and sell books, pamphlets and three-peso bills (which are all the more valuable if they have Che Guevara’s signature on them). He is a sort of antiques dealer who travels from town to town collecting what he later sells to tourists.

“I don’t bother them, I do things in a more spontaneous fashion. I’ve had my best days just sitting here, at a park bench, after talking about politics, economics or baseball. They like that. Then you take something out and offer it to them, as though it weren’t that important,” he explains.

More and more are the locals who wait for a tourist bus to arrive and stalk the first foreigner they run into to offer them their services. The drivers and guides do not appear to be bothered by this and become involved in the transaction on occasion.

Some see these efforts as an unavoidable consequence of the need to survive, others look upon it as stains on the island’s landscape, at a time when the Cuba is becoming one of the most attractive destinations in the world.