The lights flickered. Celia1 looked up from her laptop. “Did the voltage drop?” she wondered, only just realizing something worse seemed to be happening. A second later, the house went dark. The city, the province, and all of Cuba.

She gathered the company papers scattered on the table and put them away. It would take a couple of hours to realize that it wasn’t just a simple blackout affecting Holguín, but another disconnection from the National Electric Power System (SEN).

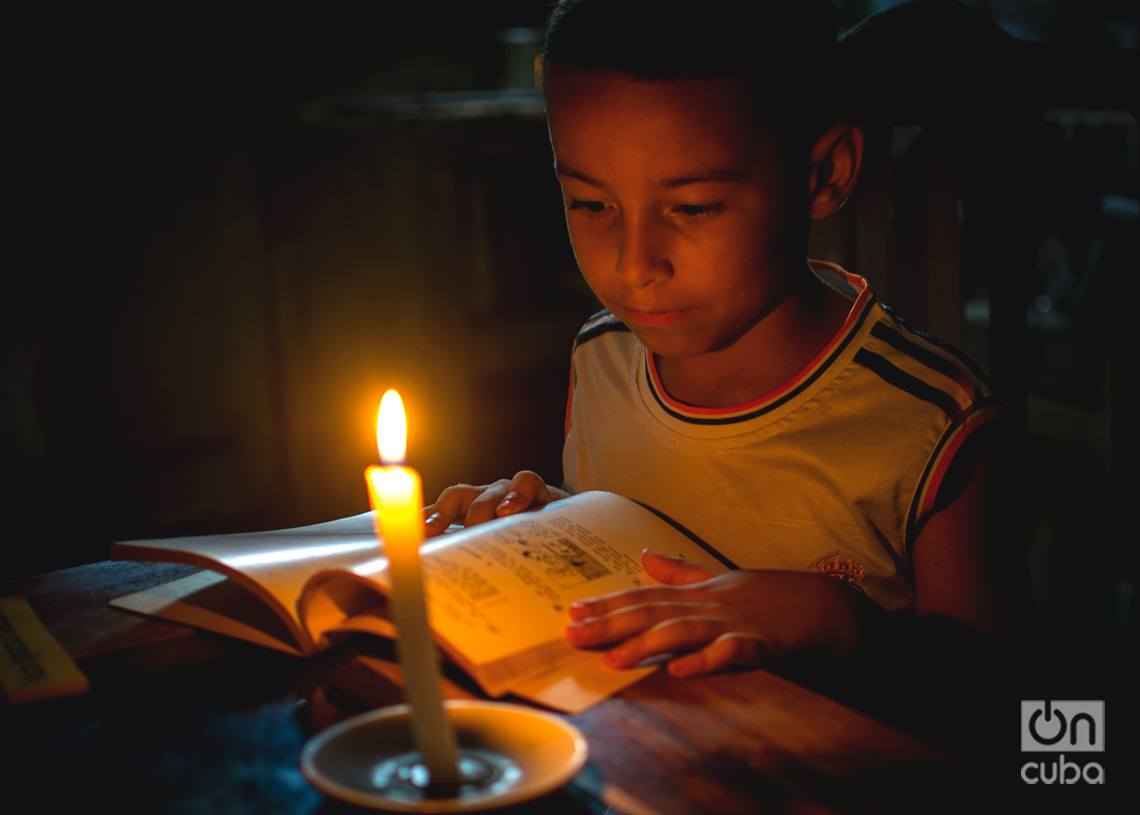

“Mom, the teacher said we have to do our homework, even if we have to use the flashlight on the phone,” her daughter warned as she took her notebooks out of her backpack and occupied the same space on the table that had previously been reserved for her mother’s papers.

Every time the scene repeats itself, Celia thinks a thousand insults, but keeps quiet: she prefers her daughter to study. At least that way, she can occupy herself with something productive. Meanwhile, sometimes at 9 p.m., she’s still black with coal on her hands and clothes, because not only does she have no electricity, but she also doesn’t have cooking gas.

“Dealing well with blackouts is as fictitious as hoping the Felton and the Guiteras2 will one day synchronize together,” she says with some sarcasm. “We supposedly live in a ‘privileged’ province because the blackouts are ‘well-planned,’ with established schedules and divided into blocks. However, the reality is different: I have days with 15 hours of blackouts and others with 9. It’s very complex to deal with a host of issues that are beyond my control: electricity, food, liquefied gas, housework, and quality time for my daughter.”

Try as she might, Celia can’t find an effective way to deal with the situation. She finds it difficult to successfully fulfill her role as a woman, mother, and leader of a private enterprise dedicated to caring for older adults and people with disabilities. The accumulated stress overwhelms her. She can’t sleep. The daily grind is so overwhelming that it seems incredible she still hasn’t lost her mind. When the power “comes on” at midnight, she gets up, charges all the equipment, and races against the clock to prepare the essentials for the next day. At 3:00 a.m., the next outage occurs, lasting until 6:00 a.m. It’s not unusual for her to wake up with dark circles under her eyes, exhausted, and in a bad mood.

A 9-year-old girl needs to be listened to, to have her questions answered, to be taken out. Celia constantly questions whether she’s a good mother. She wants to achieve this, but finds it increasingly difficult. She rarely gets to play with her. The little time she manages to spend with her is consumed by checking her homework.

“There are days when I look around and think, ‘Sorry, today is pizza day,’ because my body no longer responds to the need to get going in the kitchen. My life revolves around electricity,” she laments.

On March 14, when the fourth mass blackout in less than six months occurred in Cuba, although she knew something like this could happen at any moment, Celia felt she couldn’t handle it all. The days without electricity returned, the fear that the food she’d gotten at such high prices would go to waste, the nights invaded by mosquitoes, and the added stress of the lack of gas, which left her only the option of cooking with charcoal in her backyard.

“At least I have that alternative,” she notes, with a certain tired resignation in her voice. “I think of those who can’t even cook for their children, and even send them to school without breakfast.”

She says this with regret, adding that the power situation was decisive in her list of sacrifices:

“I would like to have another child, but it’s not possible this way. If by chance I reconsider, I look at my neighbor, 25 years old with a baby barely three months old, and I realize that would be completely crazy: no human being deserves this stress, much less a child.”

“Traumas of this time”

The most recent general blackout was caused by a failure at a substation on the outskirts of Havana, which completely shut down the SEN. The country was without electricity for more than 24 hours. In some areas, the outages extended beyond 48 hours (the shortest blackout period experienced nationwide).

Blackouts are a part of family life across the island, with some differences in areas of economic interest, where outages tend to be less frequent or last less time. The stark inequality among citizens is manifested daily in discontent on social media.

The continuous power outages affect the quality of life of millions of people and naturally impact responsible parenting, with a particular physical and emotional strain on mothers. Iris, a young woman from Granma living in Holguín, experiences this daily. She went to study there, got married, and had a child. While preparing her one-year-old’s milk in complete darkness, she sends me audio clips telling me about her experience:

“Blackouts have been with us since before giving birth. We slept poorly, and it was difficult to do household chores, but now with a baby, everything is different.

“I still have nightmares about those first months of breastfeeding, on demand. Suddenly, I’d find myself thinking: ‘The washing machine finished one load, I have to do another; lunch is half cooked; I have to refill the water tank, and without electricity, the turbine won’t work.’ Who can concentrate on breastfeeding with all that on their mind? The situation didn’t improve when the baby started complementary feeding. In the midst of all this, we went almost three months without being able to buy liquefied gas.”

Iris is cheerful and witty. At 36, she tries to find the fun side of life; however, it hasn’t been easy lately: “I feel like I’ve aged a decade,” she says without hiding her distress.

When her neighborhood has power in the morning, she prepares two days’ worth of food for her son. She also does laundry. In contrast, on the mornings when the power is out, she cleans and organizes the house.

“Those days are hard because we have no power from 6 p.m. until midnight. I have to race to prepare the milk, boil the cloth diapers (I can’t afford disposable ones), have the food ready, and everything else that’s essential in a house.”

She’s lucky to have rechargeable lamps and fans so that, when the electricity goes out, the baby is “comfortable,” if that’s even possible in such a situation. She and her husband work their magic to keep the child from getting stressed.

“Since I haven’t returned to work, I can handle the situation, but then I’ll have to get up early to prepare breakfast, get ahead on tasks, and arrive on time. I don’t know if it will be possible.”

This new mother hasn’t been able to fulfill her goal of keeping her smile; she’s always worried and against the clock.

“No playing on the floor with the baby or unplanned outings, because it makes me late to cook, wash, iron, or use any electrical equipment. I always thought about having more than one child, but forget it. There are traumas from this illogical time that won’t go away. Of all this time, I’m left with my boy’s happiness when I open my fan. I hope that for him all of life’s ups and downs, now imperceptible, are a celebration.”

No quality time

According to Iris, in the city of Holguín, the scheduling of power outages is a limiting factor. There’s always something important to do that requires electricity. On the day they have power from 6 a.m. to noon, the blackout will last until 6 p.m. Then they’ll turn it off again from midnight to 3 a.m. The following day, the blackout will occur at the opposite times.

While this situation represents an extraordinary effort for mothers in the city of Holguín, those who live in other municipalities complain that the situation is worse.

“I never know when the power will go out or what time it will come back on. When it comes on, I don’t think about resting, but rather making the most of it, almost always to prepare meals,” says Yisel, a mother of two school-age children.

They live in Levisa, a small town in the municipality of Mayarí, about 100 kilometers from Holguín. Yisel says they also have a system for scheduling electrical outages; they know the schedules in advance, but they aren’t followed.

“This creates enormous stress. If the blackout catches me at work, I’m constantly thinking that, when I get back, I’ll have to light a charcoal stove to cook the children’s food. When I know the power will be cut off at 6 a.m., I get up at 4 a.m. to get ahead on lunch. I try to do everything, but I don’t accomplish anything with the quality it deserves: not caring for the children, not work, not life itself,” she complains.

Yisel rarely wakes up in a good mood. Sometimes she accidentally shouts or urges her children to eat breakfast quickly. If they don’t hurry, they’ll have to brush their teeth and get dressed without electricity. Weekends aren’t any better either. When the power is turned on, she has to take advantage of the time to do laundry, especially school uniforms. Often, half the clothes are left wet in the washing machine, and she has to finish the work herself, scrubbing and rinsing by hand.

“I can’t give my children the attention they deserve. I don’t have time to read them stories, hug them, or spend time with them as a family. I don’t feel like I’m fully fulfilling my role as a mother either. I’m forced to tell them, ‘Do your homework before the power goes out,’ even if they’ve just gotten home from school. They complain about having to study nonstop, but they know there will be no electricity later. Sometimes we spend up to three days sleeping without power, and understandably, they wake up tired because they didn’t sleep well.”

As much as Yisel tries to organize herself so her children get to school early, so they have a regular meal and bedtime schedule, and to spend time with them talking, she rarely succeeds.

In addition to the scheduled blackouts, there are days when she is surprised by “extra plans,” that is, power outages due to low generation, a lack of fuel, or a breakdown.

Sometimes, the desire to finish chores quickly and spend quality time with her children makes her ask for permission from work to leave early and take advantage of the electricity at home, but when she arrives, she discovers that it has been cut off without warning. Despondency and hopelessness overcome her.

“It’s not fair that my children can’t even watch a movie on TV. I refuse to believe this is the only way to live here,” she laments.

Beyond the numbers

In March 2024, Holguín faced a 70 MW deficit during normal hours, with peaks of 120 MW during critical hours. According to the Electricity Union, under the block rotation scheme, “only 25% of affected customers complied with the plan; for the rest, it was impossible to plan and meet schedules.”

A year later, during the last month, the deficit ranged between 10 MW and 152 MW, with municipalities such as Moa, Banes, and Gibara reporting recurring outages.

The province’s electricity union constantly updates the affected blocks (1, 2, 3, and 4) through its Telegram channel, which demonstrates the instability of generation.

According to the Electricity Union (UNE), the national deficit reached 1,870 MW last February, the worst of the year. This situation is linked to breakdowns at thermoelectric plants and dependence on imported fuels.

The lack of foreign currency to import fuel and spare parts has made blackouts a daily reality. Among the short-term solutions, the government has insisted on highlighting is solar generation, although for now it is insufficient to resolve the crisis.

Blackouts in Cuba, especially in provinces like Holguín, are not only a technical or economic problem, but also have a profound impact on the daily lives of families, particularly mothers.

The stories of Celia, Iris, and Yisel illustrate how these power outages affect people’s quality of life and mental and emotional health.

In a context where planning is essential for family well-being, unpredictable and prolonged blackouts generate constant stress and a sense of uncertainty.

Furthermore, the lack of access to basic services such as liquefied gas increases the risk of accidents and respiratory illnesses due to the use of alternative methods, such as coal or kerosene, for cooking both inside homes and in backyards or the basements of multi-family buildings.

The experiences of these three Holguín mothers attest to the fact that, beyond the numbers and power deficits, some lives and families deserve attention and effective solutions.

________________________________________

Notes:

1 Pseudonyms and one real name have been used.

2 Refers to the Antonio Guiteras thermoelectric plant in Matanzas and the Lidio Ramón Pérez (Felton) plant in Holguín. Both plants are fundamental to the Cuban electric power system. Breakdowns at these plants, especially Felton, have been a significant factor in the regional and national electricity shortage.