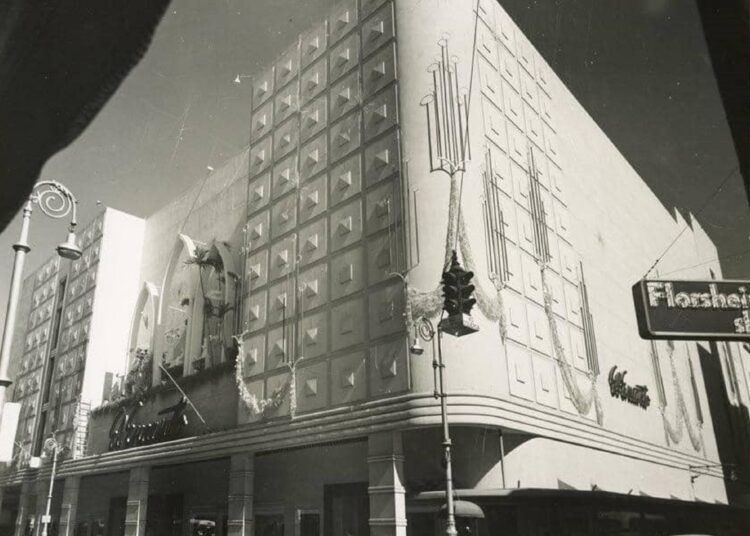

El Encanto! Never did any establishment have a better or more fitting name. At least that’s what El Libro de Cuba and the testimonies of former employees and customers who frequented that place claim. Its architectural design, magnificent as a palace, distinguished it among the city’s emblems; its majesty instilled in those who beheld it the same awe as an ant frozen before a sugar castle.

Proclaimed in advertisements as “more than a store, a national institution,” El Encanto (meaning The Enchantment in English) was the jewel in the crown of Galiano Street, an avenue where more than one entrepreneurial dream flourished.

However, the splendors of yesteryear vanished suddenly, leaving only an echo of melancholy, photographs and memories that contrast sharply with the harsh reality.

That building, which before being engulfed in flames stood impressively, as a symbol of modernity, and which for decades served as the world’s fashion stock exchange, was replaced by a park where people wander or sit, their eyes fixed on their belongings. It’s a metaphor for the transformations that have marked the island: where once there were charm and hope, today there are tales of suffering and disillusionment, repressed by the mists of time.

Casa de las Cinco Palmas

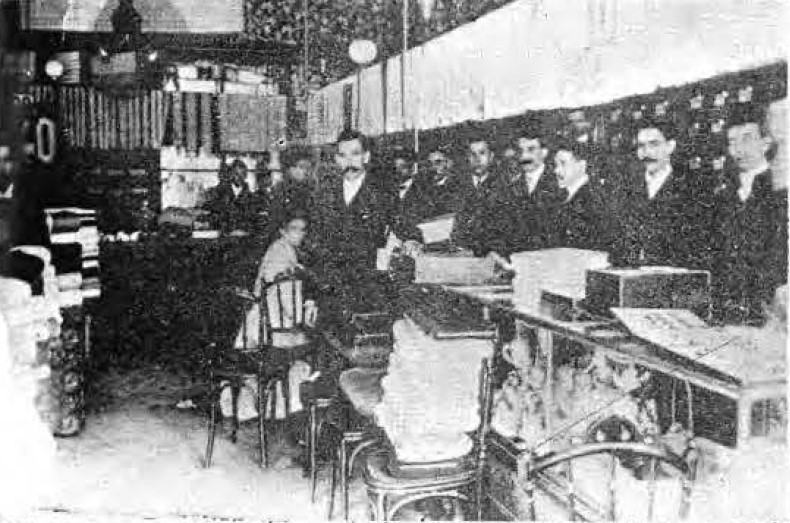

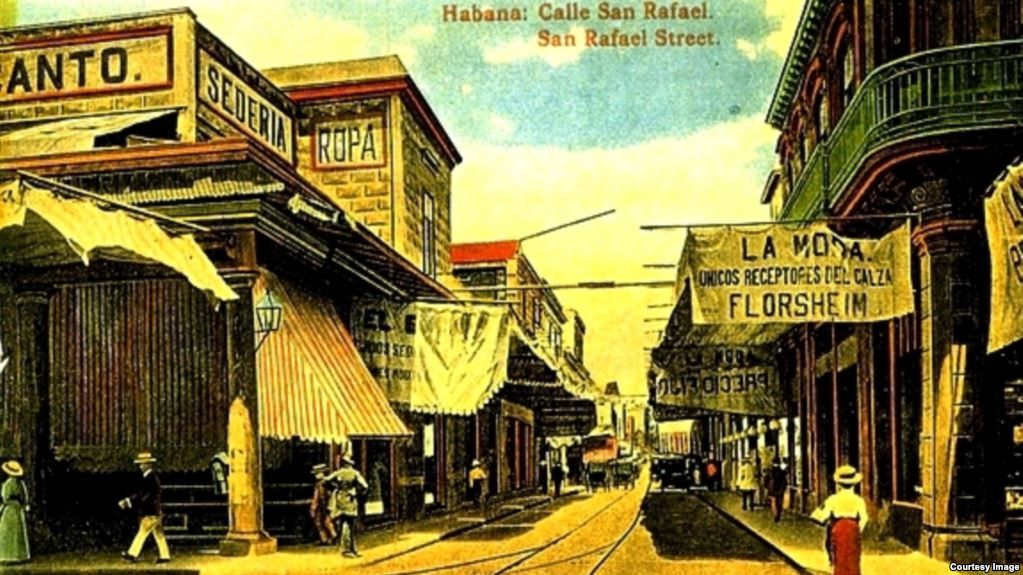

It was 1888 when José Solís García, from Asturias, fueled by nostalgia and the desire to build his fortune, opened a small store called El Encanto at number 85 Galiano Street, on the corner of San Rafael. The small shop sold fabrics, shoes and household goods. By the time the Spaniard planted his flag in Havana’s commercial epicenter, the Galiano arcades had railings, horse-drawn streetcars climbed San Rafael towards Cerro and Jesús del Monte, the clamor and stench imposed their grotesque authority, and the sidewalk bore the sign favored by the “ineffable women” who lingered there with their razor-sharp smiles.

Preceded by his distinctive pointed mustache, José Solís arrived in Havana in 1885 and established his first clothing store in the town of Guanabacoa. He soon brought his younger brother, Bernardo, into the venture, and another countryman completed the equation. Aquilino Entrialgo, whom the Solís brothers hired as a clerk, showed a knack for business and experienced a meteoric rise until he had the opportunity to participate fully in the business. It has been said repeatedly that the three of them created the firm “Solís, Entrialgo y Cia.” in 1900. In the February 3, 1916 edition of the Diario de la Marina, it is clearly stated that the company was established — retroactively — in September 1915, after the dissolution of the commercial company “Solís, Hno. y Cía.”

Under the motto “El Encanto has to be enchanting,” the mustachioed Don Pepe and his team implemented a business policy based on internal promotions for results, motivating salaries and a constant pursuit of quality customer service. A great business must be — the founding partners emphasized — an agent for the consumer in relation to production and market centers; a service that the public pays for and that, therefore, must be imbued with the public’s expectations and trust. This ideal allowed El Encanto to etch its brand into the collective consciousness of families and see its sales volume multiply.

As its influence spread like wildfire, El Encanto continued to build its prestige and acquire more land, which in practical terms translated into unstoppable expansion through the acquisition of neighboring plots and residences until it dominated almost an entire city block.

The original silk store, occupying 300 square meters on “the corner of sin,” would transform into a cosmopolitan corporation.

In short, this is the legend, with its share of both accuracy and inaccuracies, that has been circulating about the origins of El Encanto. However, a delving into primary sources brings to light other interesting and omitted facts, such as that the store was curiously founded in April (the same month in which it would meet its tragic end), that due to the leisurely pace of life in the 19th century, there wasn’t much demand, which limited its progress in its early stages, and that, lacking large over-the-counter sales, they were pioneers in home delivery.

Much less known is that it was then called the Casa de las Cinco Palmas. The Diario de la Marina of March 1, 1890, invited “those interested in good footwear without spending a lot of money” to buy shoes and boots imported from Menorca at a new shoe store “which bears the name El Encanto, perhaps because its owner has the magic touch to enchant his customers.” Regarding the nickname, the newspaper explained: “There are five beautiful palm trees on the property, their green crowns reaching a great height. The continuous rustling of these palms is a delight to those who frequent the store. Perhaps, readers, El Encanto owes its name to this.”

In its October 8, 1893 edition, the newspaper itself reported on the commercial bait of offering “good and cheap” items, and returned to the symbolic palm fronds: “After careful consideration, the owner of the El Encanto shoe store — located on San Rafael near Galiano — has decided to extend until the end of this October the sale of shoes and boots of different styles and types for ladies, gentlemen and children, which are sold there at extremely low prices, with the laudable purpose of providing a benefit to the inhabitants of Havana, who are suffering under the weight of the economic crisis that is squeezing everyone’s pockets. El Encanto, the establishment that beats it all when it comes to palm trees, as it has five in its historic courtyard, has also established fashion days: Mondays, Wednesdays and Saturdays, on which it will offer its patrons real and effective, legitimate and authentic ‘bargains’.”

A store of enchantments

By 1930, not a single brick remained of the original building. El Encanto was a grand department store in the style of Le Bon Marché in Paris, considered not only the most prestigious store in Cuba but also the first establishment to implement the department store model. It was the starting point, the nucleus from which provincial branches began to branch out over time. Camagüey, Santiago de Cuba, Varadero, Cienfuegos, Holguín and Santa Clara, among other cities — more than a dozen in total — had their own Encantos.

In 1948, a renovation of the flagship store began, culminating the following year with the inauguration of what would be its final venue. The atmosphere of the brand-new building was luxurious: air-conditioned with a fragrance, sophisticated elevators, escalators, uniformed sales staff who spoke English and adhered to strict codes of conduct in their service, and doormen at the entrance who opened the doors for eager shoppers.

The exteriors were no less impressive: they laid the sidewalks in white granite with wavy stripes of green granite, and on special occasions they adorned the facades with extraordinary fanfare at Christmas. Another undeniable success of the El Encanto department store was having its own industrial division to supply itself with clothing, which included a workshop next to the building and a factory in the Ayestarán neighborhood.

But if anything seemed sensational to locals and tourists alike, it was the splendid window displays, where mannequins showcased form-fitting dresses and all kinds of practical and dazzling garments under spotlights. They seemed to come to life spectacularly, like in the Nutcracker ballet. In fact, there was a department dedicated solely to maintaining them and changing the decorations every Friday.

Some families turned their Sunday outings into a parade past those enchanting shop windows, where even the poor would stand lost in thought, pressing their noses against the glass, until the stern guard touched their shoulder and signaled them to move on. Because our world has always been — and always will be — divided between the opulent and the “vulnerable”; just as, in the end, a pane of glass separates us from life and death.

The shopping center had five floors and 65 departments, each with its own distinct character. The ground floor housed the men’s department, men’s shoe store, jewelry, perfumery, cosmetics, books and the photography studio. The second floor housed the gifts and decorations section, considered one of the most beautiful for its exquisitely crafted glassware, Baccarat bottles, silver cutlery, hand-carved tableware, and Murano exquisite glass. It also included departments for tailoring, hats, record players, the English Salon and fabrics. The third floor focused on women’s fashion, featuring the Teen Age section and the renowned French Salon. The fourth floor was also among the most popular, housing toys, children’s footwear and Club 21 (for young men). The fifth floor contained offices, a mattress department, appliances and furniture.

With representatives and purchasing offices in New York, London, Paris, Barcelona, Madrid, Vienna and Naples, the store windows were overflowing with a diverse assortment of goods from all corners of the world, catering to the most refined tastes. Italian papier-mâché dolls with moving eyes and real hair, electric trains, Cadillac toy cars with pedals and a horn, Naturalizer shoes, Kayser stockings, Portrait of Dorothy Gray cosmetics, Chanel perfumes, Japanese parasols.… In short, one could purchase an unimaginable array of imported items without needing a passport. Moreover, the store was among the first to accept credit cards and offer rewards to loyal customers.

There, other Asturians like César Rodríguez, who later opened his own chain of Ultra department stores, and his relatives Pepín Fernández and Ramón Areces, received their training and held various positions. The experience and techniques they acquired there allowed them to found Galerías Preciados and El Corte Inglés upon their return to Spain, department stores that revolutionized commerce in that country.

This is how fashion was sold

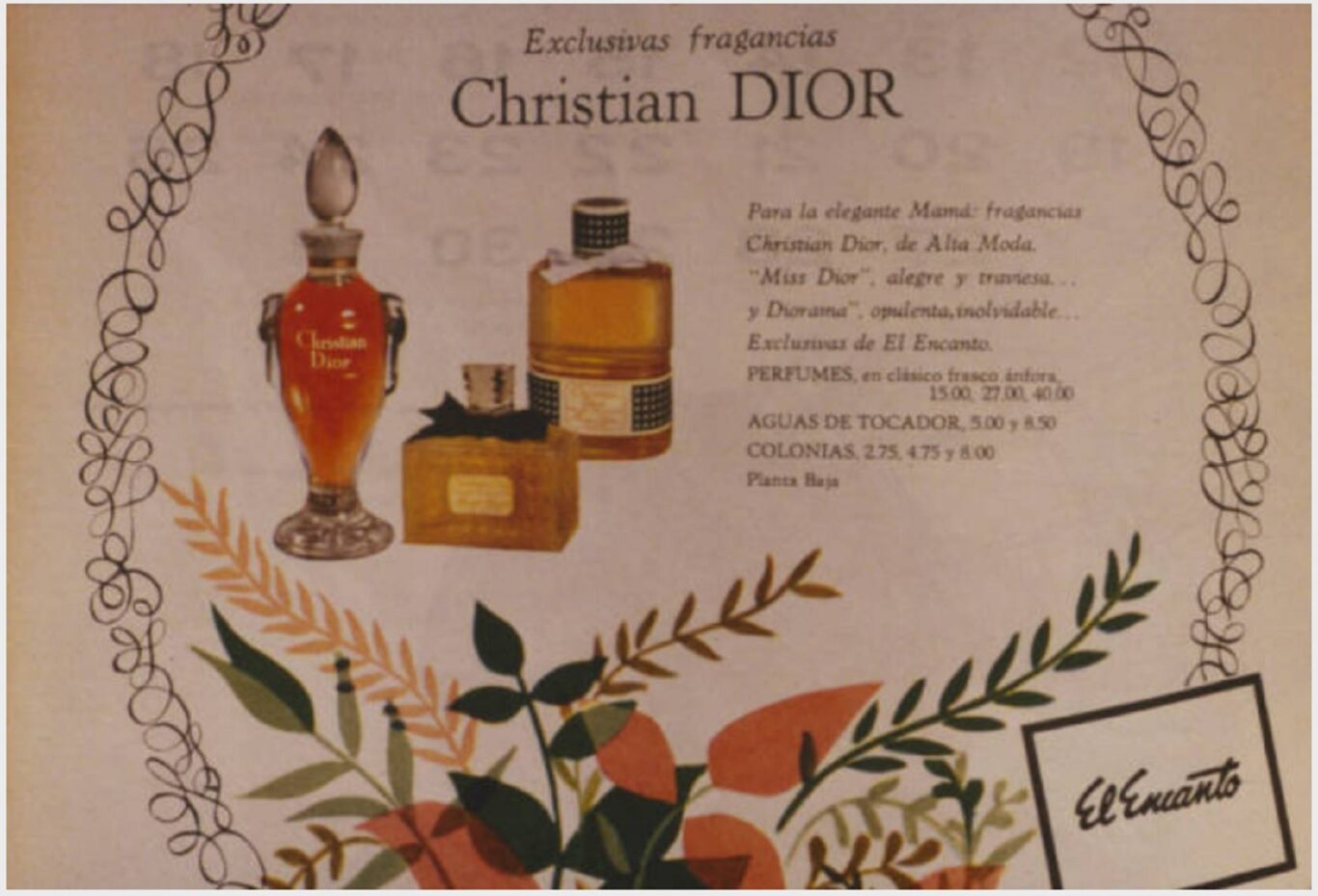

Anyone wishing to wear clothing by Dior and its fragrances in the 1950s could only satisfy their expensive desires in Paris or at El Encanto in Havana. Thanks to its renown, the Cuban establishment obtained a license to sell the brand of the famous Christian Dior.

It is known that the fashion designer was somewhat superstitious and wary of airplanes; even so, he didn’t hesitate to buy a ticket to Havana and in 1956 landed with the hope of seeing in person the store that held the exclusive rights to his creations. The designer was accompanied by some of his models and held a fashion show at the Country Club. The event, organized by El Encanto and the French Embassy in Cuba, was attended by 1,500 guests.

There was no political or business figure, or a fashion and entertainment world celebrity active in the city who couldn’t resist touring the department store. “Being in Havana and not going into El Encanto was like coming to the capital and not having your picture taken on the steps of the Capitol Building,” argues journalist Leonardo Depestre in Cien sucesos memorables en La Habana. The list of visitors is extensive and illustrious. During his fortuitous stopover in December 1930, the genius Albert Einstein bought a “jipijapa” hat there and, at the request of the elder Solís, agreed to have his portrait taken in the studio.

Several Hollywood stars became familiar faces to the employees and staff. John Wayne ordered custom-made shirts from the tailor; Ray Milland stocked up on sportswear; Tyrone Power, Cesar Romero, Pedro Vargas, Errol Flynn and even Cosa Nostra trustee Meyer Lansky visited the men’s department to buy Italian silk shirts and ties. Miroslava Stern, a Czech actress who made a career in Mexican films, insisted that her movie costumes come from El Encanto. María Félix preferred the French Salon, which imitated a room in the Palace of Versailles and offered personalized service to ladies requesting the “unique and unrepeatable” trousseaus of Manet, the in-house designer.

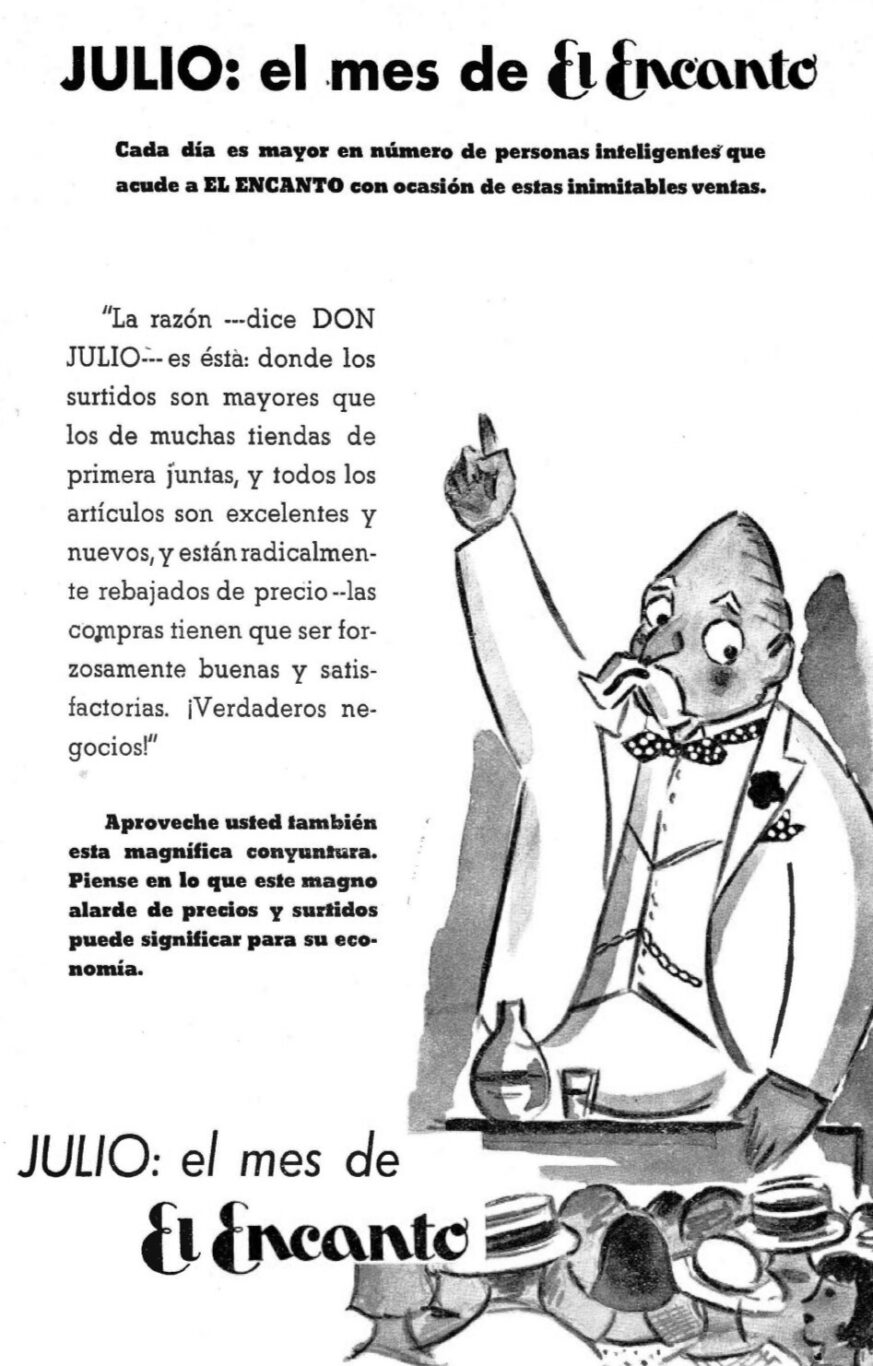

The “superstore” image was backed by an enviable organizational structure and a groundbreaking communication system. El Encanto was a pioneer in business intelligence, inventory control, marketing and advertising investment in newspapers and magazines, including international publications like Vogue. We can still verify in those archive pages that their expert advertisers “enchanted” customers based on the philosophy of the “unique” product, with messages saturated with hyperbole and focusing their arguments on the exclusivity, components and benefits of their items.

But El Encanto didn’t limit itself to the chic retail model; the management expanded its charitable activities and its integration into the sociocultural landscape. Exhibitions, concerts and conferences were held in the upstairs Green Room.

Starting in 1934, they championed the alliance between private businesses and intellectuals by establishing the Justo de Lara Annual Award, consisting of a diploma and one thousand pesos for the best opinion piece published in the national press. The first recipient was Jorge Mañach, with “El estilo de la Revolución” — in which he highlighted the need for Cuba’s complete renewal — and until its expiration in 1957, the initiative honored 24 gems of Cuban journalism.

Since El Encanto burned down.…

On the night of April 13, 1961, the department store — by then nationalized by the Revolution — closed, as usual, around seven o’clock. Shortly after, two bombs treacherously hidden in the clothing section exploded. Like a living dragon, the fire crawled through the five floors, devouring one ddepartment after another, until it reduced the colossal building to a crater of rubble and ash. The terrorist act left one fatality, Fe del Valle, and 18 wounded; three thousand people lost their jobs that dark day.

“Ever since El Encanto burned down, Havana feels like a provincial town. To think they used to call it the Paris of the Caribbean; at least that’s what the tourists and the prostitutes said. Havana is more like a Tegucigalpa of the Caribbean, not only because they destroyed El Encanto and there are few good things in the stores, but also because of the people,” the protagonist’s alter ego in Memories of Underdevelopment states categorically; while a danzón plays in the background and Sergio’s telescope focuses on Martí’s aphorism about the dilemma of accepting our bitter (wine) destiny.

The almost legendary building, a temple to elegance and an emblem of scrupulous service, has joined the infamous list of architectural losses and to the detriment of real estate in a city with a canopy of wonder, but which has progressed to the point of irreversibility; to the point of seeming condemned to never rise from its miseries and incapable of salvaging its shattered vanity. The site where the proud spirit of the royal palm once took root, at the foot of whose trunk dynamic Spaniards raised to the sky an offering of fervor for the future, never again had the same enchantment.