I’m in Panna Maria, Karnes County, Texas, a small Polish settlement located 46 miles from Seguin on Texas Hwy 123 N. It is a warm and clear Sunday. It seems as if not even the tiniest particle of dust was floating in the air. Chance has brought me here, very close to a small rural complex named Cestohowa, exactly the same name of the city where my nephews live in Poland, near the Warta River: Czestochowa, in Polish; Cestohowa, in English; Chestojova, in Spanish.

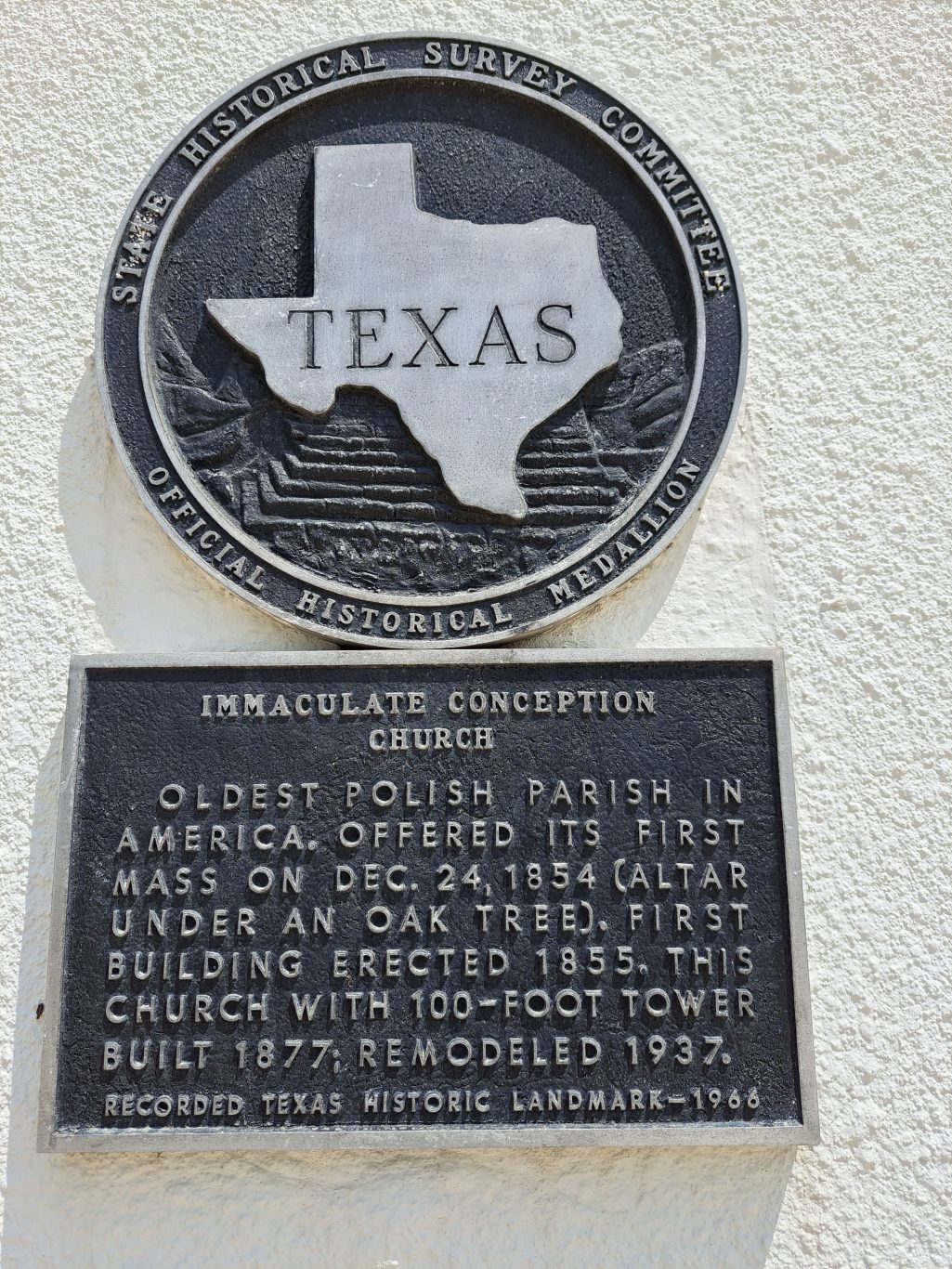

In the small office where local history is preserved, I learn that the town was founded by emigrants who arrived from Poland on December 24, 1854, and that the congregation’s first mass was celebrated precisely on that Christmas morning. So Panna Maria (Virgin Mary) is the oldest Polish colony in the United States, home to the first Polish church — of the same name — and Catholic school. Today, the descendants of Polish Texans claim to be around a quarter of a million, of the ten million descendants of people from that nation who, I’m told, live throughout the United States.

I go to the church, a Gothic-style building that rises, slightly, in the middle of the intense green of the manicured lawn. It is the evolution of the church founded in 1873, remodeled in the 1930s and with some touches from the present.

There are few parishioners. The altar is profusely decorated with natural flowers. I think it may be dressed up for a wedding. Someone clarifies to me that in a few hours there will be a wake. A couple catches my attention: she has Asian features, he looks Latino. They are sitting close together, four benches in front of me. I take photos discreetly; it is difficult to disturb the peace that is breathed there. The man turns around and looks at me as if disapproving of my use of the camera. With a gesture I tell him not to worry, that I’m not photographing them. He doesn’t seem very convinced.

II

Now it’s Tuesday. I’m still in deep Texas, I travel through small cities or towns that repeat the layout of the train station, the modest markets, fast food restaurants, family businesses, the post office, the gas station, the barbershop, the churches — several, of different denominations — the bar. and bank branches. In this tiny city, whose name I cannot record, the German imprint is noticeable, another of the strong emigrations that this state in the southwestern center of the country has received in various waves.

It’s one in the afternoon and the sun is beating down. There is little to do and much less to see. I go to the barbershop. I can spend my time there until they come to pick me up to return me to New Braunfels, where my family lives. It’s difficult to tell how I got here. I’m looking for stories for my column. And barbershops are a good place to socialize and find out about extraordinary or curious facts.

The room is empty. The barber flips through, without much interest, an automobile magazine. He notices me and invites me to take the chair. A haircut in Texas, before the pandemic, cost $20; now, depending on the place’s rank, the price can be double. I won’t know until he finishes the job. In any case, it will be a lot for my precarious economy, but I have no option if I want to stop emulating the hairy guy from Mayajigua.

“You’re the one who took photos in the church,” I hear behind me; my English is bad, but it’s enough to understand; his is good, although with a big accent.

“We can speak in Spanish,” I reply, still in amazement. “Cuban?”

He doesn’t affirm. Nor does he deny. I was right. I ask him if he has been in town for a long time. “Quite a bit,” he replies. He starts doing his job. I want to know if he is the man who was with the Chinese woman in the church. “Vietnamese,” he corrects me. He asks if I was photographing them. I tell him all about my Polish family. I was taking photos of the stained-glass windows and statues of saints to show my nephews. I feel like he still doesn’t believe me.

“What are you concerned about?”

“You can’t be photographing people here. For less than that they’ll shoot you.”

“Are you hiding in this hole in the world?”

“Hole is where I came from. And no, I’m not hiding from anyone. Or yes, maybe from myself.”

“I’m a journalist. I would like to know your story, have a conversation with you that could turn into an interview.”

“No. I’m a man of no importance. Nothing that’s happened to me up to this point is of interest.”

“Everyone carries an interesting story; you just have to know how to discover it and tell it.”

“Something like ‘everyone has their bolero’?” he mocks.

“Exactly”.

“No, forget it.”

“Are you afraid that, if I publish our conversation, your family and friends will find out where you are?”

“They know. I already told you: there’s no intrigue.”

“Aren’t you curious to know who I’m? What I’m doing here?”

“No. We Cubans are everywhere. We do all kinds of things.”

“Are there many in this town?”

“As far as I know, it’s just me. There are Mexicans and Guatemalans, but we don’t mix.”

He finishes giving me a haircut. A simple cut, with scissors, that takes five years off my shoulders.

“How much do I owe you?”

“Nothing. It’s my good deed today. But don’t keep bugging me, okay?”

I thank him, although I don’t promise him anything.

It’s not the first time it’s happened to me. I have found Cubans in other countries who, knowing that I belong to the tribe, have not charged me for their services or the merchandise they sell. This ranges from my eyeglasses in the Canary Islands to an ENT consultation in Houston. In Manila, Philippines, the airline employee’s compatriot passed my luggage without weighing it….

I go out into the inclemency again. It should be at least 40 degrees Celsius in the sun. The train station, about 300 meters away, is empty. It looks like a movie set. People no longer travel on trains, which have only been left for freight transportation. I could lie down on one of the dark wooden benches to let the hours pass; the shadow and silence invite, but I’m afraid I might fall asleep.

I haven’t eaten anything since breakfast. Nearby there is a small Mexican restaurant. It is run by a couple who, in turn, are the owners. At a secluded table, a child does his homework. He himself will take my order in a few minutes, when he puts the notebooks in his backpack. I order tacos: one of tinga, one of lengua and one of pastor. “With everything?” the boy asks me. Yes, I answer, but with little chili; and very cold water to drink.

While I wait, I check my messages. Friends and family are fine, the world still sucks. I dispatch two or three work matters. My editor reminds me that they expect the column at prime time tomorrow. I answer that he shouldn’t worry, that it’s guaranteed. I’m the one who worries, since I have nothing in the pipeline. I’m having a hard time writing. I’ve been many days away from my home in El Vedado. That must be taking its toll on my usual good disposition for work.

I go back to the barbershop. There are people inside. The Cuban doesn’t see me. Now there is another barber, working in the adjacent chair; judging by his reddish hair and his six feet, he is evidently a gringo. I settle into one of the chairs in outside the barbershop. I sleep a little. Then, I listen to music with my headphones: Arcaño, danzones; I get a little excited. With Cubanness it happens like with health: one spends the first half of one’s life trying to lose it, and the second trying to recover it…. The clock strikes 4. In an hour my son will come. He goes out to work and drops me off in any town or city along the route.

The Cuban looks out and is surprised to see me.

“I thought you were already in Havana.”

“How do you know I’m from Havana?”

“Because of the pronunciation. You are one of those who say ‘cacne’ and ‘pacque.’”

I think he’s giving me a chance to resume the dialogue. I ask him which province he’s from. He pretends not to hear. I want to know if he’s finished working. “For today, yes.” I ask if there is a place in town where I can have a good espresso, I invite. “In my home,” he says, smiling amusedly. “But I’m not going to invite you.” I explain to him that I wasn’t expecting him to do so, that I have nowhere to go until they pick me up in a while. He looks at me, hesitating. He says to come with him, the house is close, but that I’m not going to go past the porch. Bingo, I think, I’ll see if I can get him to loosen up a little.

Along the way I find out that he traveled from Havana to Moscow, that he slept clandestinely in the hostels of his old school in Ivanovo, that since he could not travel directly to Yuma ― I respect his terms ― he flew to Stockholm: six years to obtain the Swedish nationality and passport. Then, legal travel to Florida, residency and nationality, a process of six more years, or something like that.

“How did you get here?”

“Driving, three days. The car, which already had its problems, stopped working on the road. It melted down there,” he points to me with his right hand ahead, “where the elevated tanks are.”

“Wasn’t this town your destination?”

“I had no destination. I planned to drive until the fuel ran out. It broke down with the tank almost full.”

We got to his home. Like all the ones in the place, it is made of wood, with sober tones. The grass where it stands is cut, although without the care that Americans put into the task. He offers me a chair in the porch. He goes to make the coffee, he says. The door remains ajar. I exercise my profession as a snoop, I peek in. The living room furniture is modest. On one of the walls, quite well framed, there is what could be a watercolor or a silkscreen by Camejo: the Havana Malecón on a rainy day, passersby with umbrellas, a bicycle leaning against the wall, a man fishing wearing a raincoat. It is a melancholic image of Havana. How did that piece get here? Did he bring it?

He comes with the coffee. Two cups. He brings up a small table and the other armchair that is in the porch. I check the aroma. It is “Cuban” coffee from Miami. I would distinguish it from any other by a mile. He sits back, sips slowly, savors. He says that so many hours standing behind the barber’s chair exhausts him. I’m interested in knowing if he was a barber in Cuba. No, he obtained the title and permit in Saint Petersburg, Florida; it helped him settle here.

The Vietnamese girl arrives, she is wearing a white coat with a monogram that I can’t read. She is younger than him, maybe five years. She kisses him Cuban style, on the lips, without the modesty imposed by the formalities of her culture. She tilts her head at me in greeting. She doesn’t ask anything. She enters the house.

“Is that your wife?”

“Sort of.”

“Did she come with you?”

“She was already here. She saved me from dying of dehydration when the car broke down. She is a nurse. She took me to her house, which is this one, and she took care of me. And so on, one day and another until we discovered that we were a couple.”

“Do you communicate in English?”

“Yes, but we talk little. The essential. Maybe that’s why we don’t fight. We are doing well. I’ve been lucky. I think it’s the same with her. On days off we go hiking, play pickleball, watch a movie. We don’t get bored.”

“You love her?”

He stares at me for a few seconds. Either he wasn’t expecting the question or he doesn’t have the answer. He leans back in the chair.

“A year ago she traveled to Hanoi to attend the funeral of her father. I thought she wasn’t coming back. When I saw her getting out of the taxi with her suitcases one Sunday, I ran to help her. I don’t usually run for anything or anyone. Maybe that answers your question.”

I know I’ve been indiscreet. I also register that my interlocutor is exceeding the limit of tolerance with me. Perhaps the unusual talkativeness is due to the infrequency with which he uses Spanish. The Spanish language pulls his tongue, I think of this cheap joke, but I don’t tell him.

“Are you in contact with Cuba, do you read the news?”

“No. I’m fed up with Cuba to the gonads. Intolerance, aggressiveness, and one-way speech are a very heavy burden. Miami is an extension of Havana. The same dog, but with a sausage collar.”

“The gonads? Did you mean cojones?”

“The gonads.”

“Can I know what your name is?”

“No.”

“And her name?”

“Neither. In Spanish it means girl who sings on the edge of the flowering rice field where buffaloes frolic, frogs croak and swallows swoop down to drink water.”

“You’re joking.”

“Think what you want.”

“Obviously you won’t allow me to take a picture of you either.”

“How did you know?”

“Look, partner, I make a living by telling stories. I’m going to have to describe this encounter. I promise not to name the town. But if I don’t even know your name, you’re going to make it very difficult for me. Can I leave you a card with my phone numbers and email in case you change your mind?”

“There’s no need. I’m not going to call you. I already told you, I’m nobody. Look, maybe there you have the title: ‘Interview with nobody.’”

My cell phone rings. It’s my son, who is arriving. “Nobody” says our conversation has come to and end. Another Cuban and I couldn’t stand it, it would be an overdose. He enters the house and comes out immediately with two well-poured cups of coffee. He puts them on the little table, and he goes back inside.

On the way to New Braunfels, my son asks me how I spent the day, if I met anyone interesting. I met Nobody, I answer.

Four months have passed since this strange encounter. Nobody hasn’t communicated. I can’t wait to publish this, interview? Maybe he will be able to read it.