The official name is Castillo de los Tres Reyes del Morro or Morro Castle, a broad term, with biblical and colonial echoes, that reflects the symbolic and military power of the Spanish crown in the Caribbean.

It was built in the late 16th century according to the plans of the Italian military engineer Battista Antonelli, with the mission of protecting the Township of San Cristóbal de La Habana from attacks by corsairs, pirates and imperial enemies.

Its construction began in 1589 and lasted for decades, with successive renovations over the centuries. Stone blocks extracted from the coastline and a combination of European techniques adapted to the tropics were used to build it.

But the Morro is much more than a stone fortress. It’s an emblem, a witness that has accompanied us for centuries and generations. For Cubans, it’s simply El Morro, a lighthouse and silent companion, overlooking a sea that sometimes separates and sometimes unites. From its tower, a story can be told that goes beyond military strategy: the history of a city that grew up watched over by its light.

It’s almost always seen from the city, sitting on the Malecón while sorrows and dreams pile up amidst the routines of everyday life. From there, the Morro seems trapped in a photograph. Motionless, silhouetted against the sky, oblivious to the bustle of the street and the ups and downs of the present.

I rarely visited it, perhaps because of this feeling of having it so close at hand. In fact, on one occasion, I was struck by the question of how we see the city from that side, through the veins of the Morro.

And there I went. To photograph its interior, walk through its cold corridors, touch the thick walls of centuries-old stones.

The experience translates into enjoying a Havana that takes on a different character. The city is drawn calmly, without sound. The pace definitely slows down from this perspective.

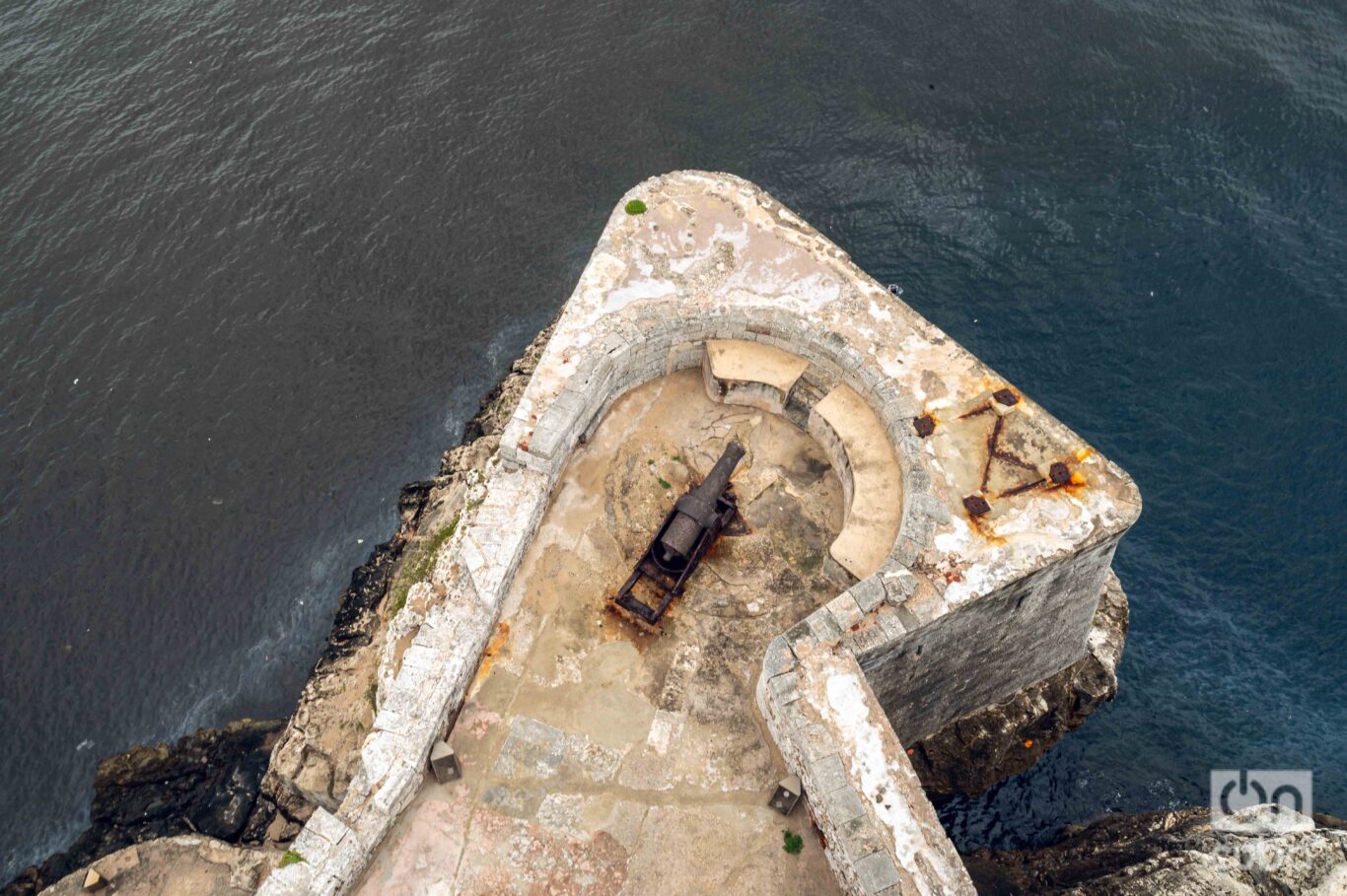

The stones retain signs of the past: impacts, inscriptions, marks of humidity. There is something beautiful in their deterioration: a sober, unadorned aesthetics that conveys weight and permanence. Where gunpowder flashes once lit and defensive strategies were honed, today you can barely hear footsteps, the laughter of a few tourists, or the voices of guides who convey the past.

Contrasts also emerge. The Morro was designed for defense and war, but today it’s part of the tourist circuit: it’s visited by students, travelers and families. Its lighthouse, built in 1845 on the site of the old watchtower and still in operation, has become a symbol of the city. It rises 25 meters above its stone base, and its light — located 44 meters high — is what guides, watches and resists from high above, marking the threshold of the bay. It used to guide sailing ships; today it is a serene lookout point from which one can contemplate Havana far from its hustle and bustle.

The sea doesn’t look like the sea. From above, it transforms into an immense blanket, a dark blue carpet that stretches out as far as sight goes. It no longer separates: it reflects. It reflects the light, the sky, as if holding within its still surface everything that once departed: rafts, boats, letters, promises.

The Malecón is also different, seen from here. From up there, it is possible to define the broken line that follows the coastal contour. You can see the neighborhoods, the worn-out buildings and how, despite everything, the city continues on its course.

Morro Castle is a symbol I always want to appear in my photos of Havana. Because, although the joke has been circulating in Cuba for years that the last one to leave will put out the Morro lighthouse, the truth is that we venerate that light, stubbornly lit, in the hope that one day it will guide us back home.