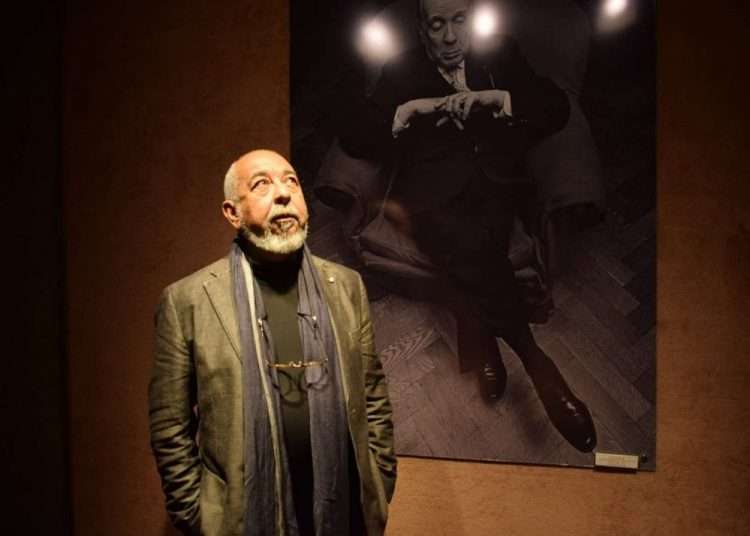

After having signed the books held by dozens of people in a long line, Leonardo Padura (Mantilla, 1955) agreed to take some photos next to a painting of Borges at the entrance to the room that bears his name in the Argentine National Library. The idea came from photographer Dante Cosenza, from the newspaper La Nación, but I took the opportunity to take a snapshot and, in the meantime, thank the writer in person for the interview he had given me via email two years ago.

Padura is a poor reader of poetry and avid for narrative, he says. I could have asked him about his relationship with the literature of this country and his relationship with the country he comes from. He had said interesting phrases, such as that “the future of Cuba has to go through a conciliation between Cubans,” after referring to what he called “air of conciliation between the two shores,” relative to the time of opening between the United States and Cuba, fostered during the Obama presidency. But the conversation was elementary. He was in a hurry and had given thousands of interviews these days. “Send me an email,” he said.

I could say something else about what was expressed during the presentation of his latest novel Personas decentes (Tusquets publishers), a story in which the author of books such as The Man Who Loved Dogs and The Novel of My Life took some pleasure, to say it someway. One was to murder a cultural censor from the 1960s, baptized as Reinaldo Quevedo, “the abominable.” Many Cuban censors are embodied in him.

Photo: Lez.

“I said, I’m going to take revenge for all the sons of bitches who persecuted, sullied and humiliated Cuban intellectuals. I’m going to tell you only two names of intellectuals who suffered through that stage: José Lezama Lima and Virgilio Piñera. Imagine from there on down how many writers, artists, musicians, professors were marginalized.”

It is the “complement” or the “definitive resolution” of a conflict already planned in his novel Máscaras, where he reflects that period of persecution and marginalization of Cuban intellectuals; dramatic, traumatic years, which did not completely cease. “I had written it from the point of view of the victims, but I told myself: I’m going to write it from the point of view of the perpetrators.”

The other pleasure was to make up a character that he had already dealt with as a journalist and whose story has haunted him for many years: the life of the pimp Alberto Yarini y Ponce de León. “He has been the most famous pimp in the history of Cuba. I began to grope that story in 1987, when I worked for a newspaper in Havana and published a feature.”

During this conversation with journalist and writer Hinde Pomeraniec, Padura recounted details such as how “Personas decentes” was the fourth title, that he had previously thought of “Huracanes tropicales,” “Delirio habanero” and “Epifanía habanera”; that decency is an “ethical judgement” and that “any society is the sum of many individuals, and if many individuals behave decently, in the end they will have a more decent society.” Also, that he wanted to return to the detective genre, because his last Mario Conde books (now in Personas decentes a guard in a friend’s restaurant) had been increasingly “more social, more existential, more philosophical.”

Regarding the alternate story: “Yarini is a very curious character, because he is a pimp, but he had, for example, the most populous burial in the first half of the 20th century. He had political participation, a political discourse. He lived off of women, but at the same time he protected certain women. He was a friend of the blacks of the port.… A man who comes from an aristocratic family. His father was the most important dentist in Cuba. So much so that the University of Havana School of Dentistry is still called Cirilo Yarini.”

Unlike other times, there were no direct references to contemporary Cuba. There were no rounds of questions either, just the conversation between Padura and Pomeraniec. Some phrases that could point to reality are said by his character Mario Conde in the novel. “It’s not fair that we live with more fear than we should,” is one of the phrases in the book that, although in the mouth of his character, Padura has used this time. And arguing about the 1970s and the meaning of a system that conditions people to the point of turning them into informers, he pointed out: “we can be afraid of pain, afraid of death, afraid of lions, afraid of frogs, but not other fears that society provokes in us, and I believe that many people moved and continue to move out of fear.”

“Fortunately, there is a slight change in policy in the 1980s and my generation benefitted from that. In the 1990s something happens, and it is that a distance is created between the creators and the institutions in Cuba; a distance that has been maintained and that we have taken advantage of as a space of freedom. Because institutions stop responding to the possibility of concretizing the work of writers and artists, and that created a space of freedom. And it has been maintained and has grown, fortunately.”

Topics that, in some way, this book deals with and were commented on:

1: decency and happiness.

2: the politically correct: “I get along very badly with the politically correct; I don’t know here, but in Spain you have to specify gender when speaking, because you have to seek equality for women in language; but a woman in Spain earns less money than a man for the same job.” “Imagine, it is being commented that in the editions of Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain, the word nigger disappears and is changed to Afro-American. It looks very nice, but that is terribly dangerous.”

3: The Rolling Stones in Cuba: the fact of seeing them live after years in which a generation was prohibited from listening to that and other music. The forbidden and its repercussions for an individual. The novel begins with a sentence, he read: “Too late.”

4: the rapprochement of Cuba and the United States: It was a “special time in the recent history of Cuba. There was a moment of euphoria. It seemed that things could change. People opened small restaurants, hostels…there were academic, religious, sports exchanges and that society was moving. It was, in the end, a parenthesis. Then Trump came and changed Obama’s policies, who changed his policies towards Cuba not because he was especially good with Cuba, but because he realized that with a change in policy, he could change things in Cuba. I believe that, effectively, it could have changed things. With Trump, the usual entrenchment returned, the cold war language, sanctions, an increased blockade, which is real, because there are many people who say that the blockade is a pretext of the Cuban government. It may be used as a pretext, but it is real.”

Leonardo Padura, who has won the Princess of Asturias Award and the National Literature Award in Cuba, turned 67 on the plane that brought him to Buenos Aires, the city he first arrived in, he said, in 1994. For a book fair, he proposed one of his works to the director of the Planeta publishing house, the conglomerate to which his publishing house belongs today. He replied: “Cuban detective novels, no.”

He also says that the same book (Pasado perfecto) had been published in Mexico and not in Cuba, as a writer with his due authorization was then entitled, which is why “an Argentine man who lived in Cuba and who had an official bureaucratic position, who was like a kind of de facto representative of all Cuban writers, told him: you know you can’t do that. This time we’ll forgive you, but don’t do it again.”

Leonardo Padura considers himself to be very generational, he believes that his generation is the best the island has ever had. Padura has a friend who, when he meets him, always blurts out the same phrase: “Damn it, what an ending we’ve had.”