Sculptures should be installed in cities and towns. Not just solemn marble statues of heroes, but also figures from everyday life: people who brought happiness to others through their work; individuals who, without intending to, become popular icons. They should be there, on the sidewalks, in doorways, in parks, as if they still walked among us. In this way, places would tangibly preserve the memory of those who truly gave them soul.

That idea came back to me when I saw on social media the news of the death of Eleuterio Estrada Valdés, the peanut vendor from Holguín. But not just any peanut vendor: “THE” peanut vendor. The man who, with his broad smile, piercing blue eyes and unmistakable calls — “I’ll trade peanuts for money,” “No money, no peanuts,” “Pretty women don’t pay, but they don’t eat either” — became an inseparable part of the soundscape of the city of parks.

The last time I saw him was a couple of years ago. I was walking through Calixto García Park when I heard, behind me, that unmistakable call. More than seeing him, I heard him.

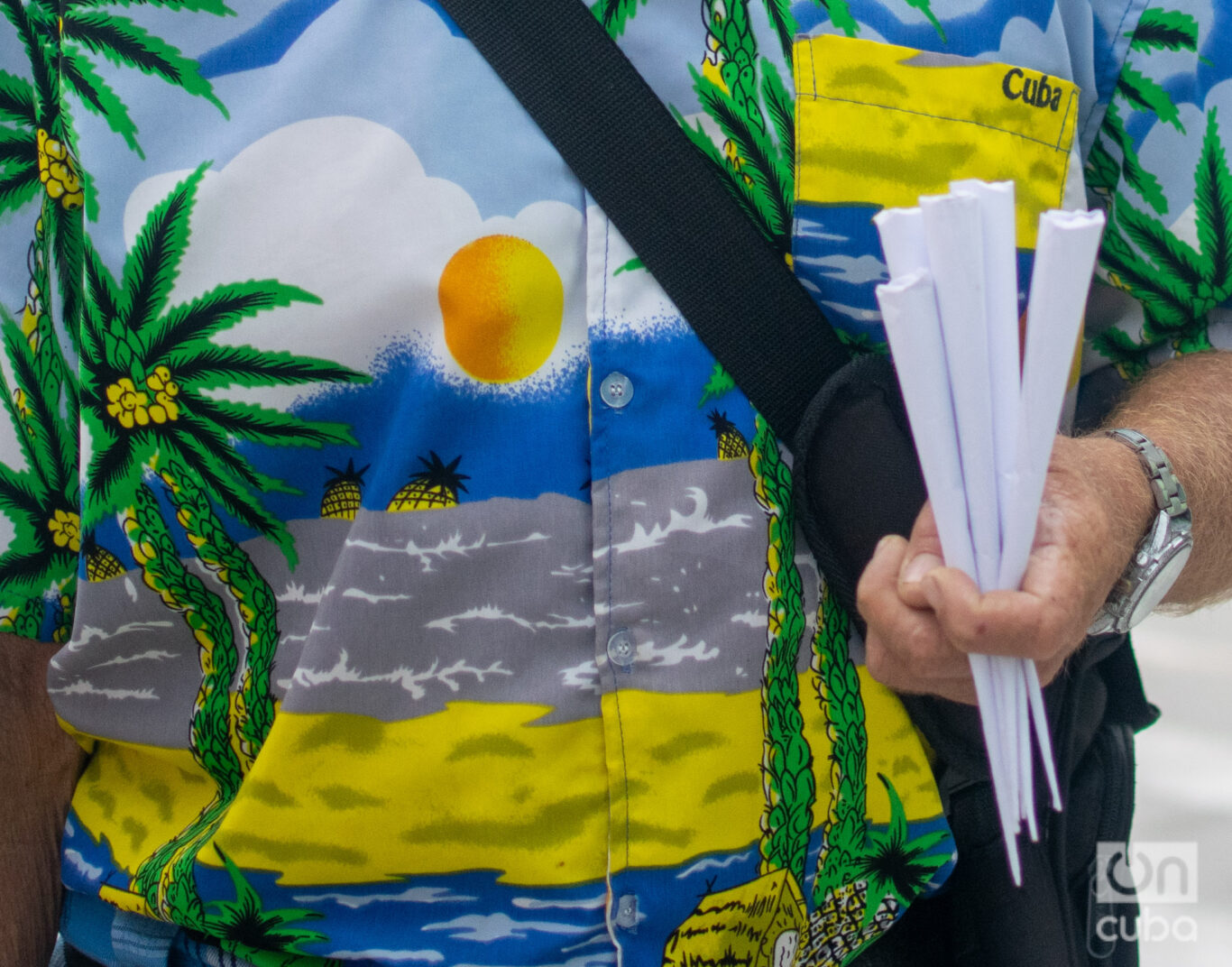

It was a reflex: I turned around, and there he was, dressed in an improbable combination of colors, like something out of a naive painting. Seeing him was, in a way, seeing my own life in Holguín flash before my eyes. His voice — playful, repetitive, almost musical, though raspy — is part of the soundtrack of that city I always return to.

I stopped him, bought some cones of peanuts and asked for a photo. He laughed, with that laugh of his that was also a street vendor’s cry.

“Compay, now with cell phones, people stop me all the time to take pictures. Even those who’ve gone up North ask me for little videos saying ‘No money, no peanuts.’”

We talked for a few minutes. He was affable as always; I was surprised to be talking for the first time with someone I’d seen hundreds of times. And I thought, as we said goodbye, how curious everything is: if it weren’t for the nostalgia I felt listening to him, I wouldn’t have taken his picture or even asked to talk. How many people like him slip through our fingers because of routine.

Eleuterio told me he was born in Bayamo and that, as a young man, he moved with his family to Holguín. For years he was a bricklayer: scaffolding, the scorching morning sun, calloused hands. But then the Special Period arrived and, like so many others, he had to reinvent himself. At a neighbor’s suggestion, he started selling peanuts. A simple job that he turned into a street performance.

I asked him where his unique street cries came from. He always told the story with pride.

“I went to offer a cone of peanuts to a man sitting in the park. He told me he didn’t have any money. I gave him the peanuts and, in return, he helped me come up with an idea right then and there: ‘I’ll trade peanuts for money.’ Then came ‘No money, no peanuts,’ and later, ‘Pretty women don’t pay, but they don’t eat either.’ And you know how it is…people laughed when they heard me coming. And of course, they bought.”

Eleuterio didn’t need anything more. With a cone of peanuts and a clever phrase, he erected a small monument of popular affection.

The news of his death spread quickly. Holguín groups on social media were filled with messages, memories, photos and recordings of his voice. Local media — and even a couple in Miami — also reported it. Something unusual for a street vendor, but natural for someone who was a symbol of the city.

“Holguín is in mourning,” wrote a community page. “We lost Eleuterio, the peanut vendor. He wasn’t just another vendor: he was an institution. His unique cry became the soundtrack of our daily lives.”

Another message summed up what many felt: “It’s incredible how such a simple and humble person earned so much praise from his community.”

Amid the sadness, one comment brought a smile to more than one face: “Up there he must be selling and calling out peanuts to the saints for money.”

It’s easy to imagine him like that: walking among the clouds, with his can, his cap and that mix of mischief and tenderness in his eyes. He’s surely already made Saint Peter laugh.

Eleuterio won’t have a statue in the park. At least not for now. But his presence — his voice, above all — will continue to resonate in the memories of those of us who grew up listening to him. That’s the invisible sculpture that remains: the one that comes alive every time someone says “money” in his own way, or when a street vendor’s cry stops us in our tracks because it reminds us of him.

Holguín, like so many cities, is also made up of anonymous people who maintain their identity without appearing in any books: vendors, street criers, drivers, singers, women watching the street from their doorways, old men smoking tobacco on a park bench; characters who add color without even knowing it. The city would be different without them.

Perhaps that’s why that street cry threw me off: it was like returning to a fragment of my childhood. Memory isn’t only written with grand events, but also with everyday voices, like the street vendor’s cries that accompany us. Like Eleuterio’s: “I’ll trade peanuts for money.”