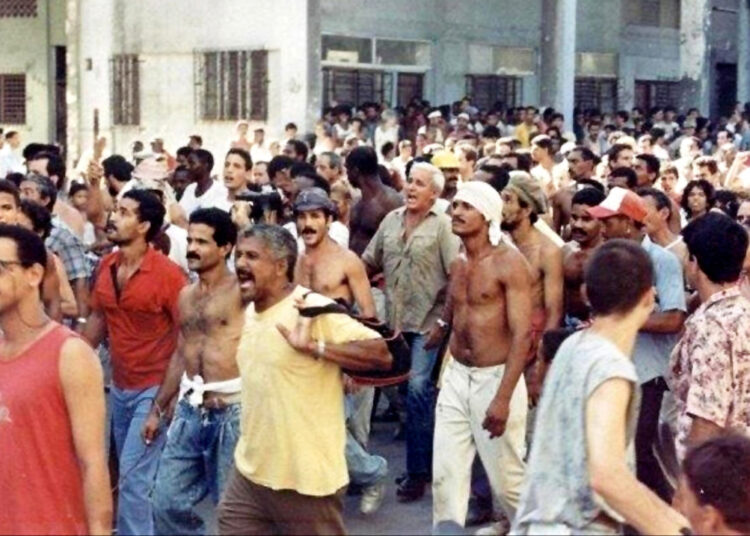

During his vacation in Cuba, Dutch photographer Karel Poort began taking photos of a demonstration outside his hotel without knowing that, sometime later, they would become some of the most iconic images of the protest along the Malecón seafront avenue, the so-called Maleconazo, the first major anti-government protest since 1959, which this Monday will be 30 years old.

In his first interview about these events, Poort recalls the frenzied minutes when he ran out of his room, with his Nikon F301 in hand, after hearing a commotion in the street. It was the afternoon of August 5, 1994, on the central Galiano street.

“I was in the shower and heard people shouting and ringing their bicycle bells in the street. I immediately grabbed my camera, some extra film and ran down the stairs,” says the 78-year-old photographer.

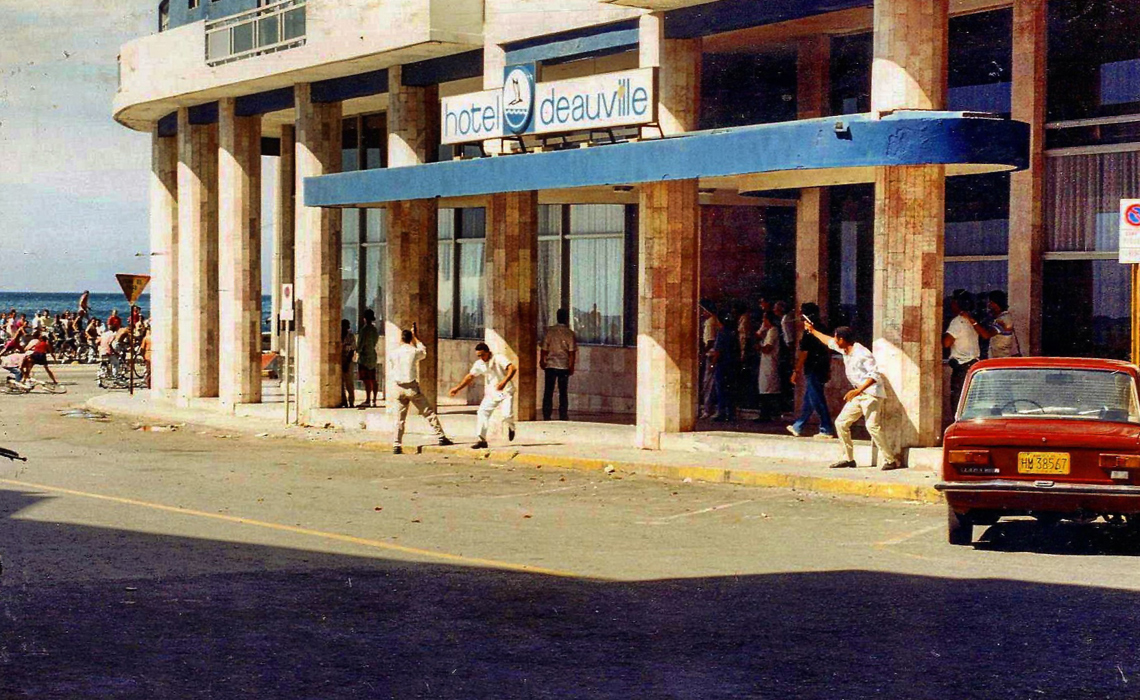

The crowd led him to the Deauville Hotel, about 400 meters from his and right in front of Havana’s Malecón seafront avenue. There, as he recalls, people were shouting at the top of their lungs: “Cuba yes, Castro no!” and “Freedom!”

Island in crisis

Poort, who at the time worked as a freelance photographer and sound engineer for Dutch television, did not know it, but the outbreak of the unrest was the result of weeks of tension.

On July 13, the tugboat ‘13 de marzo’ had sunk after its occupants had stolen it to emigrate to the United States; 37 people died.

The survivors blamed the Coast Guard for ramming them, while the Cuban government claimed it was an accident.

In 1994, the island was in the middle of the Special Period, the economic crisis that hit the country hard after the disappearance of the Soviet Union and the fall of the socialist bloc in Europe.

The rumor of a significant exodus of people to the U.S. coasts led the authorities to establish a maritime blockade in front of the Cuban capital.

Irritated, the islanders demonstrated in numbers that had not been seen since the triumph of Fidel Castro’s revolution.

When the Dutchman arrived at the hotel in front of the Malecón, a Cuban approached him and said: “Keep taking photos and show in your country the disaster that there is here.”

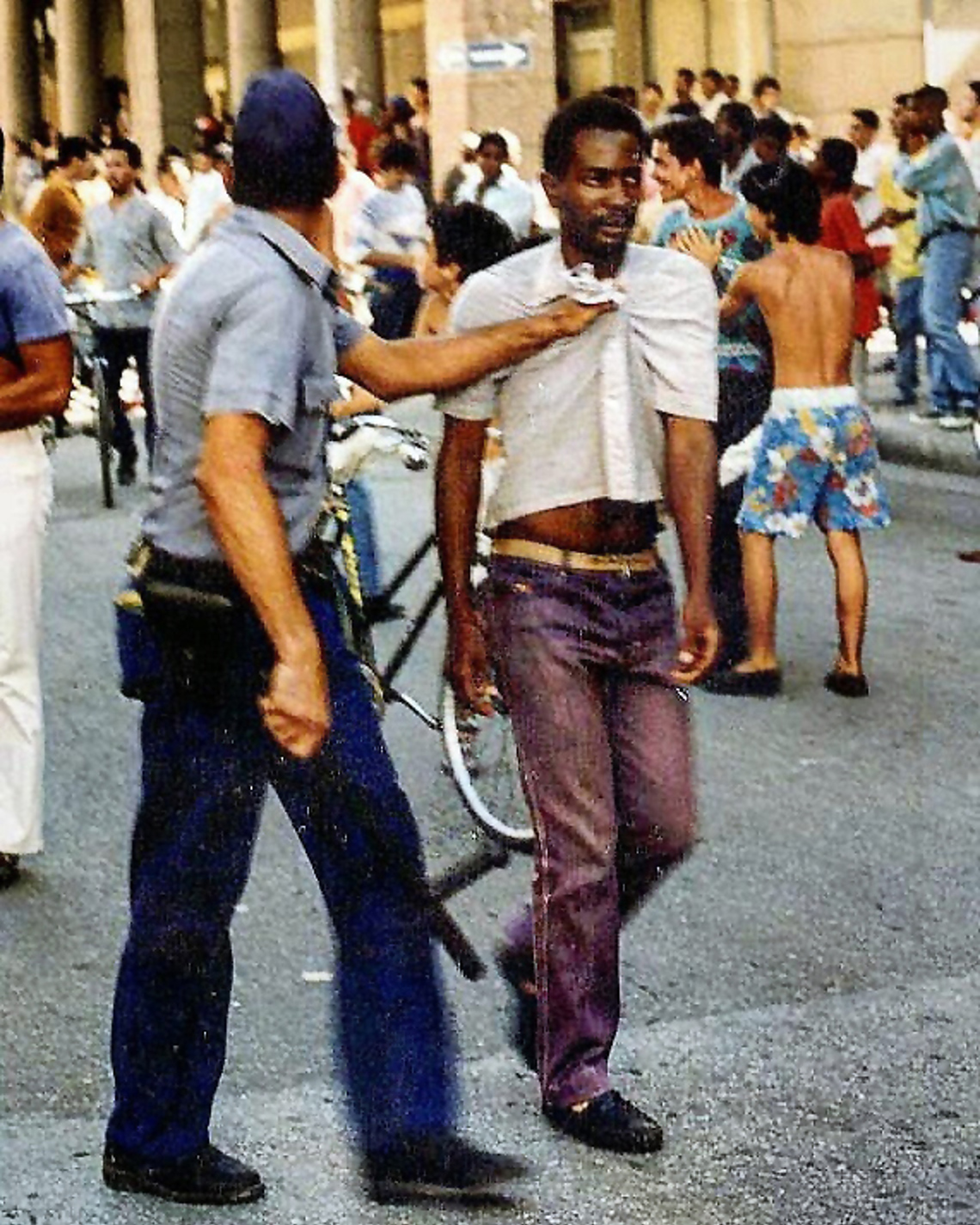

“While that was happening, a group of plainclothes police arrived at the Deauville and started shooting wildly,” he recalls.

Among the thirty photos that Poort gave to EFE, several can be seen of a man, wearing dark glasses, a white shirt and khaki pants, with a short firearm in his hand.

In one of them, he is in front of the hotel, pointing upwards; in another, he is pointing directly at Poort and in others he is seen running towards where the protesters were.

Half an hour after those events, a patrol car stopped behind the photographer: “Three police officers ordered me to hand over the rolls of film and the camera. They grabbed me and, miraculously, I managed to get away and ran as fast as I could to my hotel…I was able to take more photos from the window of my room,” he adds.

The next day, he picked up a piece of paper with the words “Long Live Free Cuba” on the pavement of the half-empty street.

A week later, then-President Fidel Castro ordered that Cubans be allowed to leave by sea. This led to the so-called rafters’ crisis: more than 30,000 left in improvised boats for the United States.

A historical memory

Accustomed to protests in the West, the Dutchman was not aware of the magnitude of what he saw until he heard a Cuban’s explanation.

When the demonstrations broke out, Poort was in the second week of his first vacation in Cuba. He visited the island nine more times until 2002.

Years later, he shared some of his photos on social networks. He does not have them printed in a special place in his house. He prefers to remember what happened as the anecdote of a historic moment that, by chance, he was able to capture even before many international media outlets that were on the island.

“I was the only one there. There were no cell phones back then. That is why those photos are so special,” he says.

Juan Carlos Espinosa.