On August 28, 1922, Emilio Bacardí gave a glimmer of hope. For him and his family, it had been an unfortunate summer, due to the worsening of his heart condition, which had left him bedridden for the last few weeks.

On that Monday morning, he felt that he was regaining strength after overcoming a heart attack three days earlier. He warmly welcomed the visit of some friends, among them the promising Fernando Ortiz, and, in the afternoon, he debated with the past fervor of a tribune about sectarian violence in Ireland, concluding that the problem lay in the fanaticism and intolerance of that society. He did not know it yet, but he would not live another day to tell the tale.

His heart stopped a couple of hours later, around six in the evening, just as the sunset began to cast its streamers of shadow around the mansion of eclectic architecture and prominent grace. Like in a scene from an anthology. It was up to Dr. Antonio Guernica to seal the death certificate with leaden handwriting and, with the scribble of death, the specter of mourning was born.

“Emilio Bacardí’s life declined peacefully and majestically, like that of a biblical patriarch, and he had, at the time of his death, the luminous melancholy of the setting sun. I still seem to see his noble and artistic bust, crowned over the bed, with all the appearances of a peaceful and happy dream. There, at the very edge of that bed, his most worthy consort, Elvira Cape de Bacardí, living and sympathetic harmony of heart and intelligence, watched over the final sleep of the great patriot and benefactor, and with silent tears, not profaned or disturbed by cries or gestures, serene and faithful like a Niobe, she paid the memory of her beloved husband the best homage of well-felt pain,” testified the journalist and friend of the family Joaquín Navarro Riera, the popular Ducazcal, in an evocation chronicle published in El Mundo on August 27, 1925.

He died in Villa Elvira, a picturesque estate on the outskirts of Santiago de Cuba whose doors were always open to those who, attracted by the charisma and magnetism of his fame, wisdom and benevolence, came to greet or meet the lofty politician, writer, patron and businessman. That was how virtuous Emilio Bacardí was.

In that part of the eastern geography, the well-known family took root, was happy and elevated its best hopes to the wind. Until they themselves took flight. Never again, with the triumph of the Revolution, was it used as a family home. After the exodus of its owners, it would have numerous uses, generally linked to the service of various groups of people. And as if the wake of the twilight that marked the autumn of the patriarch were becoming eternal — Gabo would say —, gray patches fell on the house and its history slipped away among the fallen leaves.

Simple name changes?

It all began with a love story, when Don Emilio — as a gift for his beloved wife — had the strange idea of baptizing with the name of Elvira the regal villa that was enclosed between the second intersection of Cuabitas, where the central train passed, mango-tree lined avenues and a hill of emerald greenery. Or did it all begin a little earlier, with a tragedy? Let’s recap.

By September 1904, in his mayoral efforts to expand educational institutions in the city, Bacardí gave up his old country house so Katherine Tingley could set up a headquarters of the Raja Yoga Academy she had founded in Point Loma, a community near San Diego, California.

At the end of the afternoon of June 27, 1907, someone at the school dropped an oil lamp and the explosion on the floor unleashed a fire that spread within minutes to the entire premises, which were then made of only wood. There were no deaths, but the material damage was considerable and the building was charred. Madame Tingley had no choice but to take her theosophy elsewhere and return the land to her sponsor.

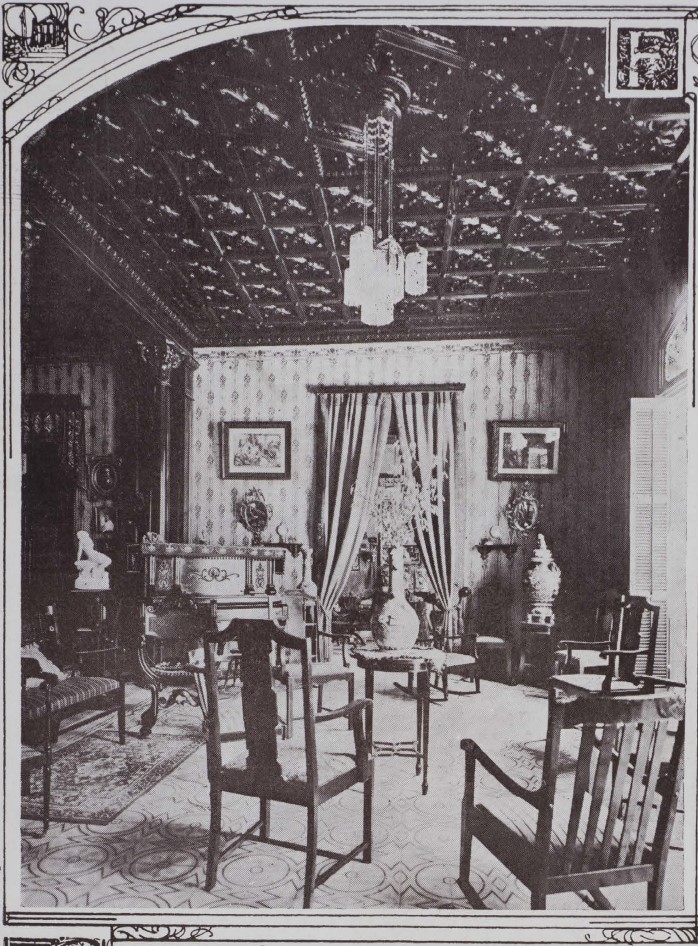

Where there were ashes, the capricious Emilio arranged to build the solid one-story house with a tower at the back that can be seen today; much larger, more comfortable and ornate than the previous one. It was accessed by a wide marble staircase, at the foot of which flower plants perfumed and gave greater prestige to a portal of Greek columns. The profusion of large windows with careful ironwork, chandeliers, fine furniture, works of art, among other baroque and decorative additions, rounded out the palatial profile. In addition to garages and service quarters. Thus Villa Elvira was born, as a revived love nest.

We could even go further back in the passages of time. I do not know exactly when the illustrious man from Santiago acquired the property. However, from archive photographs and references in the nineteenth-century press it is easy to know that it initially belonged to his ancestors on his father’s side.

Towards April 1893, the Diario de la Marina reported in three lines the death “on his Los Cocos estate” — which was what it was called at that time, although other sources mention El Cocal — of the merchant José Bacardí Masó. Of Catalan origin, he was the brother of Don Facundo, and together they had founded the rum industry that quickly achieved fame. So José was Emilio’s paternal uncle, and as if that were not enough, as he had no recognized descendants he ended up naming his nephew as his executor. It is presumed that it came to him by way of inheritance, although there is no notarial proof.

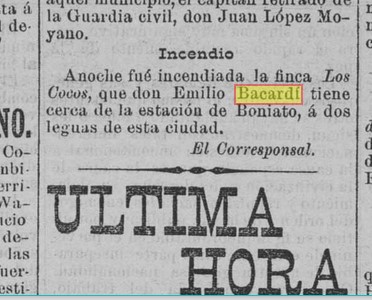

At the beginning of July 1895, the estate went up in flames. The chroniclers suggest that it was a case of sabotage by some Spanish guerrilla group in retaliation for the conspiratorial work of the Bacardí family, in particular of Emilio, who under the pseudonym Phoción was the head of an efficient clandestine network that guaranteed the sending of soldiers and resources to the insurgent army. These activities cost him his arrest in the summer of 1896 and a year of exile on the Chafarinas Islands, off the coast of Morocco. During this period, the estate must have been registered under the partnership of Enrique Schueg and Pedro Ramos, surely in the role of frontmen to protect it from a legal point of view from a possible expropriation by the authorities.

On May 12, 1900, this alliance was dissolved and the house returned to being under the Bacardí seal. This is confirmed by his first will, written on the early date of January 25, 1902, when he suffered dizziness that made him fear a fatal congestion: “I therefore arrange as follows.… The Arroyo Viajaca estate, on state land, was purchased as the right of possession for my daughter Marina, so put it in her name.” This was another way of identifying the property within the family, alluding to the stream that crossed nearby.

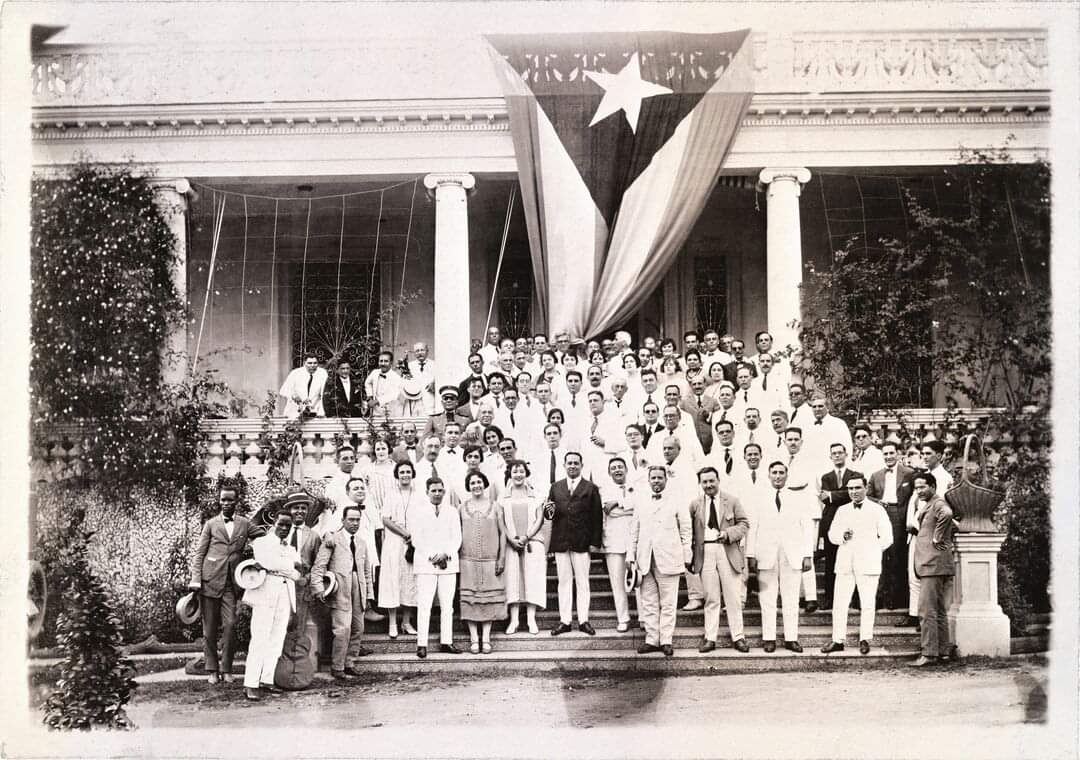

During the following years it would be the country house or recreational home of the family domiciled two blocks from Céspedes Park, in the heart of the city. In the Cuabitas residence they found restful rest and privacy far from the daily business and city bustle. There they organized banquets and family parties, hosted friends, celebrated champagne balls, party meetings and sociocultural events.

An idyllic estate

“Why don’t we stay here forever, enjoying this clear and bucolic environment that leaves the soul in paroxysm?” Don Emilio must have made a similar invitation to his wife — or vice versa — so that the couple decided to move permanently to the rural area of Cuabitas, about six kilometers north of Santiago, between Quintero and Boniato, which became their habitual residence in the last decade of his life, after giving up politics to devote himself entirely to writing and philanthropy.

Although today it seems somewhat bleak, Cuabitas sparkles to the passerby its old “residential neighborhood” appearance. Given its tranquility and dreamlike nature, it was chosen early on by the cream of Santiago society to build their summer houses. Count Duany — millionaire of the 19th century —, the Bravo Correoso, the Berenguer, the Henríquez Ureña lived here; in 1898 Mariano Corona printed El Cubano Libre there and Calixto García set up camp in the so-called Casa Azul; in 1905 the journalist and patriot Desiderio Fajardo Ortiz, El Cautivo, died there. Closer to the present, among the names linked to the town we have the poet and art critic Antonio Desquirón (1946-2014) and Reinaldo Cedeño, champion of Cuban literary and cultural journalism. Cuabitas is a town with history and heritage.

For Don Emilio it was not only a soothing refuge. He found inspiration there and could almost always be found reading in his library, writing novels and articles, exchanging correspondence with family and friends. He took advantage of this to compose some volumes of Crónicas de Santiago de Cuba, his masterpiece. He also welcomed friends and travelers from all over the world who later left enchanted by the Bacardís’ hospitality.

To give you an idea, the long list of personalities welcomed in that home included Ana de Quesada, widow of Céspedes; the former Mambí president Salvador Cisneros Betancourt; General Freyre de Andrade, Secretary of Provincial Government; María Luisa Dolz, Diego Tamayo and participants of the Fifth Conference of Charity and Correction in 1905; and the U.S. military delegation attending the unveiling of monuments in 1906 in the former scenes of the war of 1898.

Bacardí shared the joy of living in an environment of whispering groves and splendid polychromatic gardens in blossom. Ever since his early years he had educated his pupils in the collection of dissimilar landscapes; he had seen the world: America, Europe, Palestine, Egypt.… His enlightenment knew no boundaries. Like a prophet he preached the understanding of human existence in communion with nature. Hence his mania for attributing metaphysical values to each piece of furniture, object, tree. The locals still speak of the Bacardí Stone, a rock placed on the hill at the back of the patio, where he used to climb and sit for hours, immersed in deep meditation. Don Emilio called it the Stone of Energy.

“The patio itself of the house is something worthy of admiration. It simulates a grotto made with all its stalactites and stalagmites. And the flowers that are artistically placed there in valuable pots are beautiful and strange,” detailed Enrique Cazade in a chronicle published by El Fígaro in July 1918.

In his tropical villa, the respectable septuagenarian enjoyed his grandchildren, Sunday barbecues and occasionally bought a lottery ticket to invest in public works whatever chance deemed to grant him. On one side of the house was the sculpture workshop of his daughter Mimí, where the artist’s prodigious hands made fantastic creatures emerge. Distributed throughout the poetic-style gardens and extensive corridors, these pieces gave the villa an exotic touch that amazed visitors. It was an extremely familiar atmosphere. A small oasis of art, nature and emotions.

Early years

During the years following the deaths of Emilio and his widow, the daughter Marina Bacardí Cape and her family remained in Villa Elvira. Following tradition, the Covani Bacardí family kept the house as a center for events for Santiago’s high society until they decided to emigrate in 1959. As occurred in countless similar cases of properties labeled “bourgeois,” the estate ended up occupied and it served successively as a militia school, a pioneer camp, a primary school and, finally, an educational center for children with special needs.

“My mother spent the Revolutionary Instruction School there, in the first years of the Revolution. I visited the place in 1972, when I was six years old. It was a pioneer camp. It still had original furniture, lamps and ornaments; I remember seeing sculptures in the basements, also in the gardens. We both have nice anecdotes from the days we spent there,” recalls Clivia Rodríguez, a Santiago native consulted via WhatsApp by this reporter for the preparation of this text.

Likewise, Rosa Rodríguez, who also has a relationship with the Villa, keeps alive the stories her mother told her about the days she spent there around 1962: “Yes, there were sculptures. As students they had access to the dining area, since most of them were in shelters built in spaces adjacent to the main house, divided for girls and boys. Inside the house some rooms were occupied, and in front, in the entrance hall, there was a tennis table where they could play.” One fine day in 1965, it was decided to move the Mariana Grajales school there, which would later become a boarding school.

Mercedes Guasch, a native of Santiago who studied there and was also interviewed for this article, told us that the children who were, as in her case, in the home for orphans located in Santa Rosa were moved there. For his part, Antonio Radamés spent his primary school life “running through those corridors,” as he told OnCuba. “There were many period things in the main house, a piano, paintings, vases, part of the furniture, but nothing that identified the former owners.”

In those first years of the Revolution, there were tense days, of just transformation for some and justified fear for others, when the eviction of objects and names began. As happened with the Bacardí factory, which became Ron Caney, Villa Elvira was also affected.

The houses, who can doubt it, contain numerous material and symbolic elements that keep the history of their owners. So the aristocratic mansion suffered more than just a name change, as it had changed owners.

There were times when the surname Bacardí became unpronounceable; he stopped being a patriot to become the mere owner of the rum company; his birthplace is not identified nor are other houses he occupied in the city preserved; for a time the bronze mask was removed from the monument erected in his memory by the magazine Acción Ciudadana in the 1950s, turning that faceless Jaimanita stone into an “innkeeper” for drivers of the nearby provincial People’s Power. Let us not forget the triumphalist attempt to erase the name from the Bacardí museum; only the infinite zeal and rectitude of the prominent intellectual and painter from Santiago, Miguel Ángel Botalín Pampín (1932-2013) prevented such a debacle. “My father told me about it firsthand. He had to explain to the high official in charge of the mission that that would be a serious mistake. Luckily they didn’t change it,” Miguel Ángel Botalín Aguiló, the son, confirmed to me.

The new school

In 2008 I had the good fortune to set foot in Villa Elvira for the first time. I went there with the help of the tireless Sara Inés Fernández, founder and coordinator of the project “De la ciudad, las calles y sus nombres” (Of the city, the streets and their names), which brings together researchers and popular chroniclers. Created on the initiative of Sara Inés in May 1999 in Santiago, and lacking an institution to support it, the project attempts — marked by the intermittency and voluntarism of its promoter, now retired — to exhume the forgotten episodes and characters of local history to restore them in neighborhood tributes.

Sara Inés, a profound connoisseur of the imprint of Emilio Bacardí and who worked for 13 years as a specialist in the homonymous museum, “deserves an ode,” as the journalist Reinaldo Cedeño brilliantly said. At the time of my visit, the place was undergoing construction work and looked dirty and chaotic.

In the outside areas, sturdy walls that had collapsed, mutilated bushes, fountains and destroyed benches were in plain sight. To make matters worse, Mimí Bacardí’s eye-catching statues, or what was left of them, lay headless, dismembered and covered by weeds in what was once the romantic garden, now unrecognizable. The residence itself also had a façade in a deplorable state, although it retained its stately aura. Inside, there were hollowed-out ceilings, peeling walls, stained floors and the spacious rooms turned into a vulgar “flea market” of construction materials.

I, a callow youth with the orphanhood of a first-timer, did not have the good sense or the courage, I confess, to speak the truth and draw attention to that atrocious attack on what was supposed to be a site of heritage value. Based on the reflection that the years bring, I understand today that those workers did not act like that out of premeditation or vileness, but because of the lack of culture that kills people, according to Martí.

We returned in 2010, to a tribute to the Favorite Son, as Bacardí is known, with hundreds of pioneers from the Mariana Grajales semi-boarding school. The remodeling work had finished and I have to admit that the house showed a somewhat more attractive face. Some original objects — almost nothing: a rickety long-case clock, a Louis XVI style dresser and a mahogany-colored kitchen shelf — were in scattered corners inside the house. I was able to save them in photos, at least. I don’t know if they are still there. I did not return.

With great fanfare on April 23, 2019, a brand-new center was inaugurated on those premises, under the new name of “Cuba-Vietnam Friendship,” aimed at providing specialized care to 120 students — from preschool to ninth grade — with physical-motor disabilities, belonging to the eastern region of the island. In order to be converted into that center, a capital investment was made that returned sumptuous graces to the place. But there is not — there never has been — a plaque from the monument commission with the legend that a hero of the country lived and died on that site. The people of Santiago remain indebted to their Quixote.

“The house is in very good condition and has a history room with photographs and articles by Don Emilio Bacardí and Elvira Cape,” the cameraman colleague from the Santiago TV channel, Andrián Fernández, tells me from a distance in a digital message. If his words are true, then a minimal work of justice has been done; and besides, it gives a hopeful light.

Five years later, the educational institution, the third of its kind in the country, is a reference in the development and social integration of young people with special needs. The old Villa Elvira is today a place full of life and humanism. A work that the Bacardí-Cape couple would approve of.

No matter how much dirt you throw or how many layers of paint you apply to the walls, there are traces that never fade. The house retains its soul. As if Bacardí had never left.