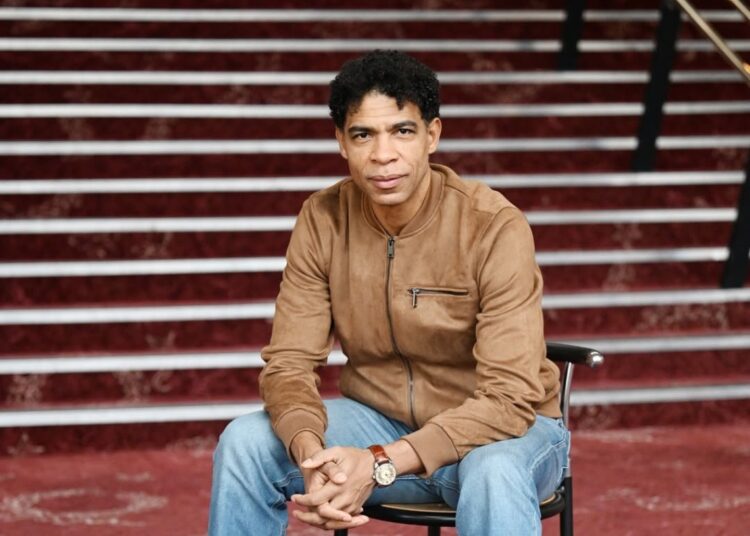

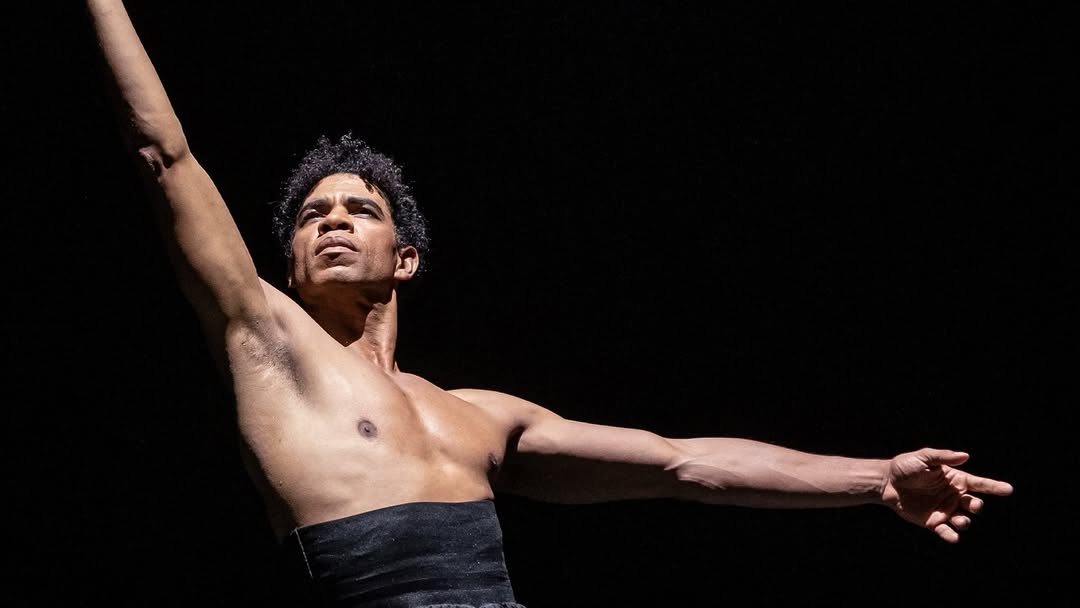

Carlos Acosta is unstoppable. That’s the impression that comes to mind when one considers all the projects the iconic Cuban dancer, at 52, is involved in. Over time, and with the certainty of having left a legacy as a performer in dance, he has demonstrated competence as a creator (Acosta Danza, Birmingham Royal Ballet), talent, vision and sensitivity as a choreographer, and even his acting skills, among other facets. Winner of the National Dance Prize in Cuba (2011) and decorated in 2014 by Queen Elizabeth II of England with the Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) medal, Acosta always manages to move people.

After Yuli (2019), the film inspired by his life and directed by the Spanish filmmaker Icíar Bollaín, audiences empathized even more with the path forged by Acosta, a path fraught with obstacles. In the world of dance, Carlos rose to become a principal dancer with London’s Royal Ballet and built a 28-year career as a leading figure in international classical dance, until he announced his retirement from the stage in 2016. That same year, he gave the first performances of the company he had founded months earlier, on September 28, 2015.

Acosta Danza was born as a vibrant combination of classical and contemporary styles, fused with elements of Cuban dance. Carlos’s dream took shape in his homeland and took root — the company’s Academy bears witness to this. Ten years later, we celebrate the first decade of existence of one of the most flourishing dance companies on the Cuban stage.

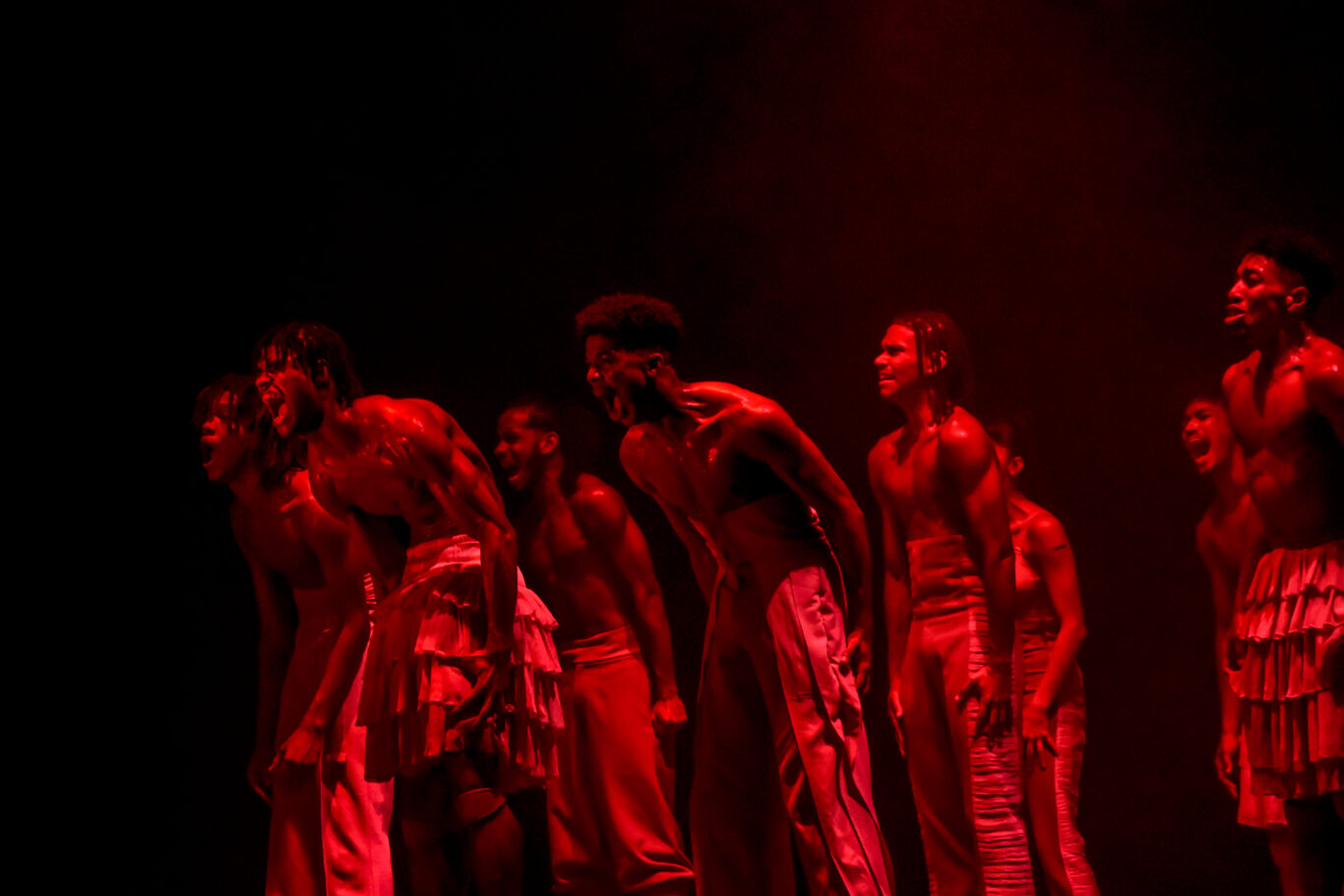

Those who attended the company’s performance season at the Avellaneda Hall of the National Theater of Cuba last September could attest to this. A decade in motion showcased a potent dose of the dance DNA that Acosta Danza has forged over all this time, from the cryptic “La ecuación” by George Céspedes, the nod to Federico García Lorca in “98 días” by Javier de Frutos, the trance-like “LLamada” by Goyo Montero, and the dose of Cuban identity and contemporary relevance in “De punta a cabo,” choreographed by Yaday Ponce based on the original by Alexis Fernández.

Now, when Carlos Acosta speaks with OnCuba about this decade of work, he does so imbued with the responsibility that comes with continuing to reap success and train generations of dancers at his academy.

Carlos isn’t one to sit back and reflect on his achievements. “If that were the case, I wouldn’t have accomplished anything. I always have a goal to achieve; ideas come to me and I try to make them a reality. You have to aspire to the sky to at least be able to get closer to it, and that’s what I do. I’m satisfied with what I’ve achieved, but that’s only part of the journey. Today I’m ensuring what tomorrow will bring. That’s my natural drive, my duty, my mission. My legacy is not yet complete.”

How would you define this decade of Acosta Danza?

I define it as a good start. When I founded the company, I always knew that achieving distinctive work would take a long time, because an identity isn’t created in five years. There’s a lot of trial and error in the beginning. Anyone familiar with the company knows we’ve done it all.

These past ten years have been incredibly intense, and we’ve set ourselves challenges to overcome, in addition to all the difficulties you encounter along the way. Artistically, Acosta Danza has done a lot: we’ve danced everything, we’ve had contemporary seasons and others dedicated entirely to classical ballet; we have works that preserve the tradition of Cuban modern dance technique or Afro-Cuban folklore, all performed by the same dancers.

They had a tough time at first because the company demanded they step outside their comfort zones, but they never said no. That courage fostered a cast always ready to do anything, and that’s how we began to distinguish ourselves. The company became known for having a highly trained and versatile group of dancers, and for offering stylistically diverse shows. We already have an audience that is truly ours, that seeks us out and waits for us. What I thought would take longer started to emerge, and although I don’t think I’ve arrived yet, we already have our own light on the dance scene.

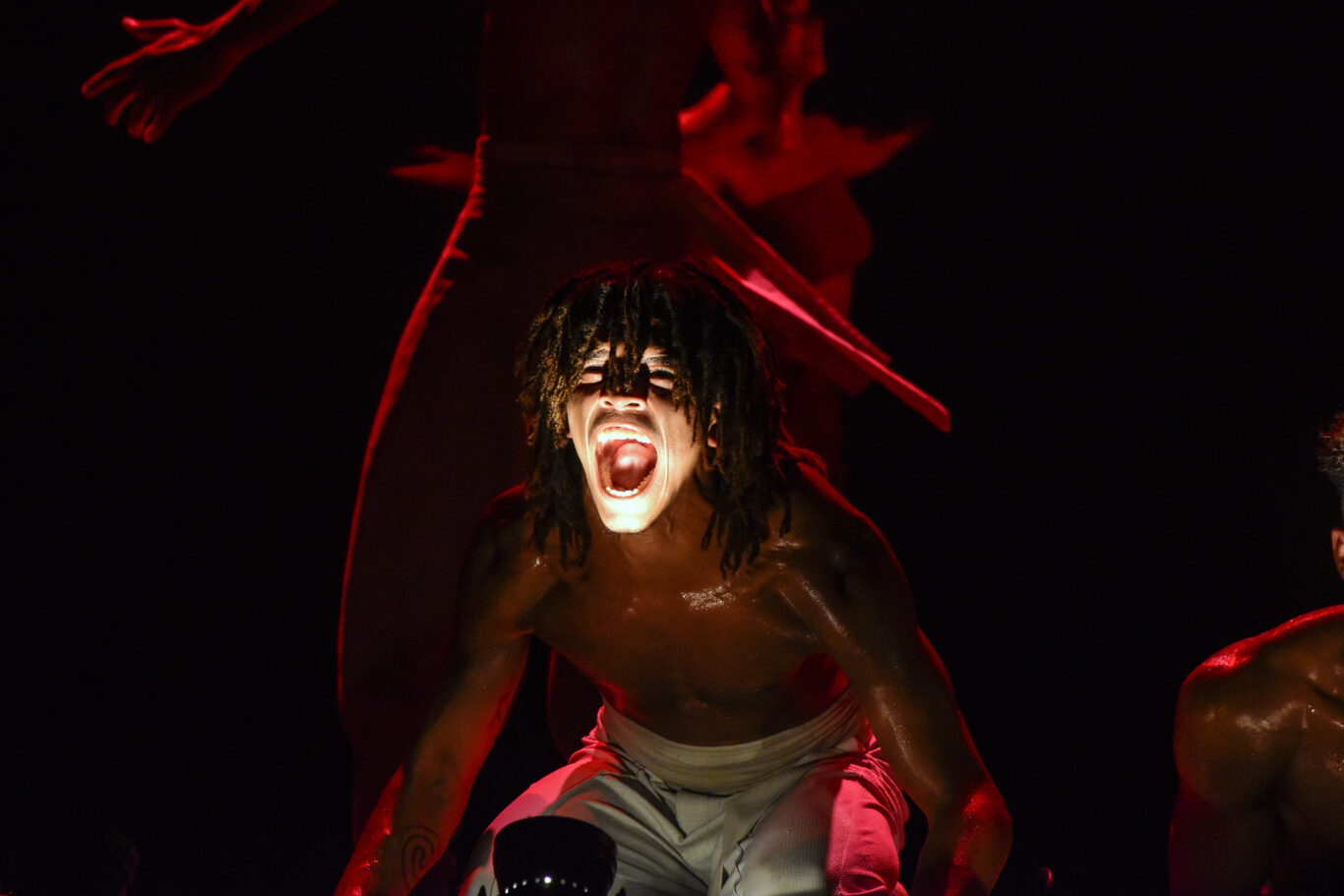

You presented a revamped cast in the recent season celebrating Acosta Danza’s 10th anniversary, young performers graduating from the company’s academy. What do you ask of your dancers when they embrace dance and work with your company? What does it take to be a performer with Acosta Danza?

They must be versatile artists, with well-trained bodies, capable of dancing any choreographic style without sacrificing quality. And I always tell them they have to work hard every day. This profession is very difficult because you’re constantly going against nature.

The body may resist, but you have to think, “I can do it,” and that mental message is transmitted to the body, which is activated and keeps going. This is a mind-body training that you have to do as a professional if you want to advance, and it guarantees everything else. Hard work can’t be hidden: you always know when a dancer is hardworking and when a company is well-trained.

I don’t like anyone to go on stage unprepared, because you have to respect the audience, and the company can’t stop. That’s why we have to work and be ready, in body and mind, for what’s coming, which in our case could be something completely unexpected.

Ten years ago you came to plant a seed in Cuba. To what extent do you think you’ve been able to reap all the desired fruits?

I think that in that sense everything has gone well. The company has developed, we’ve built a reputation. We have an audience that follows us and waits for us. There are many young people who dream of being part of Acosta Danza and we have an academy that trains the dancers we need. Some of those students have also gone on to join other companies, so, in a way, we’ve collaborated with the work of other national groups. Now we have other projects that will contribute to the development of the country’s cultural life.

How much has Carlos Acosta’s dream of making dance in Cuba changed in this decade?

That dream hasn’t changed. It’s true that ten years ago the country’s situation was very different: the economic conditions were different and the winds were very favorable for creating new things. Right now, we are living through difficult times that are testing us. Even in other parts of the world, after the pandemic, many people’s views on the need to invest in the arts have unfortunately changed.

We are experiencing a complicated landscape, and not only for artists. But we are still here, planning for the future, thinking about what we can do to develop.

It’s true that our performances in Cuba are not as frequent as they were six years ago because the current circumstances force us to schedule our work differently in order to continue existing. But Cuba is our base of operations: we plan everything here, our roots, our school and our future are here. Cuban culture is the lifeblood that defines us, and we strive to ensure that the Cuban audience is the first to see our work.

How do you envision the next ten years for Acosta Danza?

For now, I see a lot of work ahead. There are things we need to redefine; we have to make decisions to mark this new era and show that we are moving forward, that there is development.

I would like to do more full-night shows, like Nutcracker in Havana. We need to work more on the fusion of different styles to achieve our own.… I have several ideas in mind, but we have to proceed carefully, think each step through.

Since 2020, you have also been the director of the Birmingham Royal Ballet. How would you define that other responsibility?

The Birmingham Royal Ballet has been a great learning experience for me. It is a large, historic company, and working there has given me greater experience as a director to take on other projects. The first major mission was to update the repertoire and thus win over new audiences. I believe that ballet has to keep pace with the times if it wants to survive. You can’t perform Swan Lake the same way you did 30 years ago.

The vocabulary of ballet is rich, allowing for thousands of combinations, and the technique continues to evolve. Today’s dancer performs things that would have been difficult to execute 50 years ago. All of this must be reflected on stage, along with technological advancements, new themes and the best thinking of our time. All of these ideas were discussed at the Birmingham Royal Ballet, and we have succeeded in turning attention to the company. It is a revitalized institution and many are awaiting our next premiere. Our show inspired by the music of Black Sabbath is an example of this.

To what extent have you allowed for feedback between the two companies, Acosta Danza and the Birmingham Royal Ballet?

The feedback happens naturally. Many of the things I learned working at the Birmingham Royal Ballet I have brought to Acosta Danza, and many ideas that I initially brought there I had already tested here. Even dancers from one company have been able to participate in shows by the other. All of that is development, enrichment.

Carlos Acosta celebrates the first anniversary of the Acosta Dance Centre in London, a space that has welcomed thousands of dancers and is establishing itself as a symbol of diversity and unity through dance. Photo: @poetryfilmproduct. Taken from Carlos Acosta’s Instagram profile.

We’ve received very good reference about Nutcracker in Havana. Is it a show you’d like to present in Cuba?

Of course, it will come to Cuba as soon as possible. That’s what we’ve wanted most since the moment we premiered it. I know Cubans will be moved, they’ll laugh and cry with the show, because they’ll see themselves represented with so much grace, color and love. Nowhere in the world will that story be better understood than in Cuba.

The difficulty lies in the fact that the show has performances scheduled for the last and first months of the year, which limits our time to bring it here and then transport all the equipment. Furthermore, the current technical conditions of Havana’s theaters don’t allow for the scale the production demands, and that would significantly increase the cost.

I believe that if we’re going to bring it, we must do it as it is. It wouldn’t be fair to make such a large investment only to ultimately sacrifice part of the show. Cuba deserves to see Nutcracker in Havana in all its splendor. That’s why it’s best to prepare the conditions well so we can present it in the country. I feel that day will be historic for us, a moment of pure joy.

As a choreographer, where do you currently choose to focus your attention? Is there a particular problem or concept that concerns you to the point of wanting to express it in a choreographic composition?

Reality always inspires. There are themes, there are struggles that must now be brought to the stage. Although working with both companies greatly limits my time, I never stop imagining future choreographies. For Acosta Danza, specifically, I’m thinking about another all-night show that, like Nutcracker, will bring together the historical with the contemporary, the national with the universal. We’ll see how it goes.

There is Cuban talent scattered all over the world. How do you see the role of Cuban dancers on the current international dance scene?

I think they continue to contribute the strength that has always defined us and, at the same time, they are learning that international ballet and dance require much more than strength.

How do you see the current state of dance, internationally, both as an art form and as a market?

Let’s just say it’s at an interesting time. Performances continue to be given in theaters, the technological level has risen, the sensibilities of this era are reflected and, at the same time, stage dance has had to refocus on the virtual world. Social media presents new stages we must navigate, and this is reshaping the entire language of theater.

I’m not saying the results will always be positive, but that’s what we’re working on. One of the main challenges is adapting an art form that has always required a live audience to thrive in virtual spaces, survive, and reinvent itself in an era where fewer people attend the theater.

Furthermore, we must consider how to engage young people who are always glued to their phones, in order to create new audiences. Our survival depends on this new struggle.