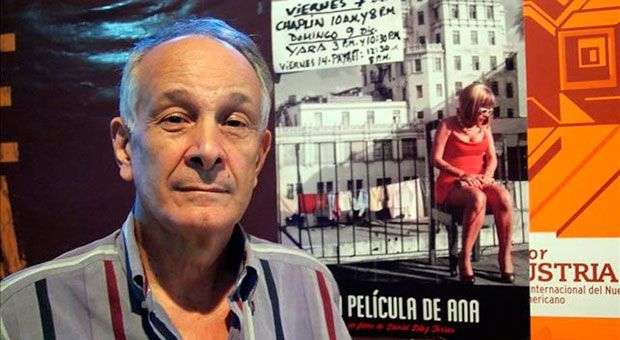

Now that ICAIC’s Young Sample (ICAIC: Cuban film Institute by its acronym in Spanish) imposes its presence, at least for all those related to the Cuban cinema as a whole, this is also the time for recalling, as every year, all that at some point was considered a contribution or a renovation. The Sample dedicates several spaces for remembering the imprint left by recently deceased Daniel Díaz Torres, one of the filmmakers most linked to the work of the youngest, while maintaining a critical spirit, always alert, smart and unprejudiced.

The sharp critical style, backed in satire, emerged when Daniel was working under the command of Santiago Alvarez, in the production of 21 editions of ICAIC’s Latin American News Bulletin, during the last five years of the 60’s. When he was interviewed about it, Daniel enjoyed highlighting three editions of the News Bulletin he was in charge of: one called La ventana, which was about a warehouse that stood out for its inefficiency and lack of order; and another two editions about some cafeterias called Los Conejitos, which were characterized by indolence, disrespect and mistreatment.He was mainly interested, as well as in several of his subsequent films, in satiricallydenouncing disorder, conformism, routine, waste, double standards, and the lack of concern by certain leaders.With the support of Santiago Alvarez, Daniel humorously illustrated the negative images taken directly from reality. In the interview in El Noticiero ICAIC y sus voces, by Mayra Alvarez, the producer states:

Sometimes humor is annoying, but I always defend it because it is a key quality of intelligence. I’m frightened by people with no sense of humor; I feel there is something missing in the mechanisms of approaching reality and connecting with others. When I talk about humor I don’t refer to mockery or hurtful jokes, it should not be identified with shallowness. Humor makes people reflect in many ways; it makes them hesitate about things they had for facts which many times are not absolute and allows finding other perspectives to deal with a certain issue.

Looking for different perspectives to approach a subject, and yet linked to the News Bulletin, Daniel produced his first four documentaries, curiously far apart from the sharp criticism that was starting to characterize him. After this five-year long training in journalism, he assumed a documentary style rather closer to depiction and chronicle, than report. Los dueños del río (1980), Madera (1980), Vaquero de montañas (1982) and Jíbaro (1982) made farmers and the rural context more visible with characters and topics that seemed to be limited to periphery.

He never drifted away from documentaries. Even in his fiction films, one can observe his need to talk about real characters, mostly contemporary, common people going through extraordinary conflicts. Magnetized by a genre that at that moment was really interesting for him, those action and violence films made by Sam Peckimpah or Don Siegel, the documentary Jibaro had notable success with the press and the audience, but its version in a full length fiction film was not that successful because it was a failed attempt to recycle the western genre through Cuban farmers.

In his second full length fiction film, Otra mujer (1986), Daniel came closer once again to a subject tackled in many occasions in the Cuban cinema: the full involvement of women in society. Otra mujer, in addition to portraying chauvinism in the unconscious mind of men, even the most revolutionary men, aims at leaving in the audience an optimistic touch in terms of realization as social being, in the character interpreted by Mirta Ibarra. In the 60’s, and due to the difficulties of men and women to cope with a tiresome and mean daily life, the main character asks the demanding official who tries to manipulate her to solve the problems in the community: “What else do you want from me? What else am I suppose to give you?”.

However, if Otra mujer ligltly tackled the issues of inefficiency, opportunism and indolence in the Cuban bureaucracy, Alicia en el pueblo de Maravillas (1991) makes use of resources from absurd comedy and satire open politically to denounce outrages occurred along the process of socialist transformation. This film emerged and brought about endless polemics on the critic function of the arts in the early 90’s, when Cuba no longer had the support of the former Soviet Union and the economic system collapsed. ICAIC came in the 90’s, which were marked by the collapse of the socialist block in Eastern Europe and the “Special period” in Cuba, a time of shortages, conflicts of values and ideological crisis. In that context, Alicia en el pueblo de Maravillas portrayed double standards and the comfort of some leaders, along with the evidence of a permanent state of surveillance and denunciation. In the beginning the film sets the keys of surrealism and absurd, when a young girl throws a man from a high bridge and the body disappears in sulfur smoke. From that moment on we enter in retrospective in the story of a young art instructor that runs away from Maravillas de Novera (anagram in Spanish for the underworld -averno), a dark and feverish town, ruled by injustice and inhabited by people removed from their positions.

Daniel’s way of acting in the Cuban cinema cannot be defined only through the stories conveyed in his films, with their corresponding positive elements and achievements. His biographical sketch would never be complete if there is no mention to the years he devoted to teaching at the International Cinema and Television School, to his work as jury in tens of national and international festivals, and his work as member of the Higher Board of the New Latin American Film Foundation, created by Gabriel García Márquez in 1985. All this matches with ICAIC after Alicia…, ICAIC of the Special Period, which was marked by a decrease in the quality of the work and in the amount of productions. When he decided to produce another film, there was only material and budget for shooting a medium length film, Quiereme y veras, which –along with Madagascar, by Fernando Perez and Melodrama by Rolando Diaz—should have made up the full length film Pronostico del Tiempo, but it never came to conclusion so Quiereme y veras was premiered independently.

By the end of this dark decade of the Cuban cinema, Daniel continued hiding his need to portray contemporariness by means of parodies of detective and spy films, in the line of KleinesTropikana (1997) andHacerse el sueco (2000), which sum up the ideological crisis, the natural enhancement of the foreign, and the lack of illusion (or disorientation) of Cubans during the Special Period. Falsehood and bad behavior acts as omnipresent dramatic devices in Kleines Tropikana and Hacerse el sueco, because both films show the existent crisis of moral values that resulted in moral, filial and psychological breaches, detriment of collective illusions and utopias, individual disorientation, all of which favored opportunism. Just as in Jibaro, or Otra mujer, or in his documentaries from the 80’s, in his latest films it is still palpable his interest in expressing the dynamics of the correlation of forces between coercive inertia and characters outcast for their rebelliousness and inconformity, humble and honest people capable of making stoic efforts. Such dramatic, even tragic, characters are developed in comedies where custom is so caustic that becomes a daily absurd.

Then, Daniel went back to documentaries with a work for the Caminos de Revolucion series and later on he produced for the Spanish television Camino al Edén (2007), which represents the challenge of directing a period melodrama, a genre rather unusual in his filmography. He also took another challenge, in Lisanka (2009), based on the referential or historical plain, in the context of two characters going through extreme situationswhich include jokes, unbridled sex, mockery of the solemn and the most ironic internal review. The movie stands out mostly when it ridicules the clash among different cultures, or when it satirizes schematic and authoritative attitudes in that epoch of initial radicalism. Form delirium, Lisanka dares to mock many of the schemes of the socialist reality, while making fun of conceit, greed and lack of vision by the opportunists, or proposes the chance for the parts involved in the conflict to show good manners with one another and to reconcile.

La película de Ana (2012) was the last film he produced and it became a caustic review of foreigners’ stereotypes on the Cuban people, whereas, between sharp or not so sharp jokes, in a way conveniently exaggerated, it reveals different common places on prostitution, the traffic of personal interests, intellectual honesty, sacrosanct vocations, and the beneficial use of personal talents. Daniel Diaz Torres, from his first to his last movie, was concerned about honesty and the Cuban identity, in order to get away from intransigence and prejudices and thus granting secular jokes a touch of nobility, intelligence and commitment.