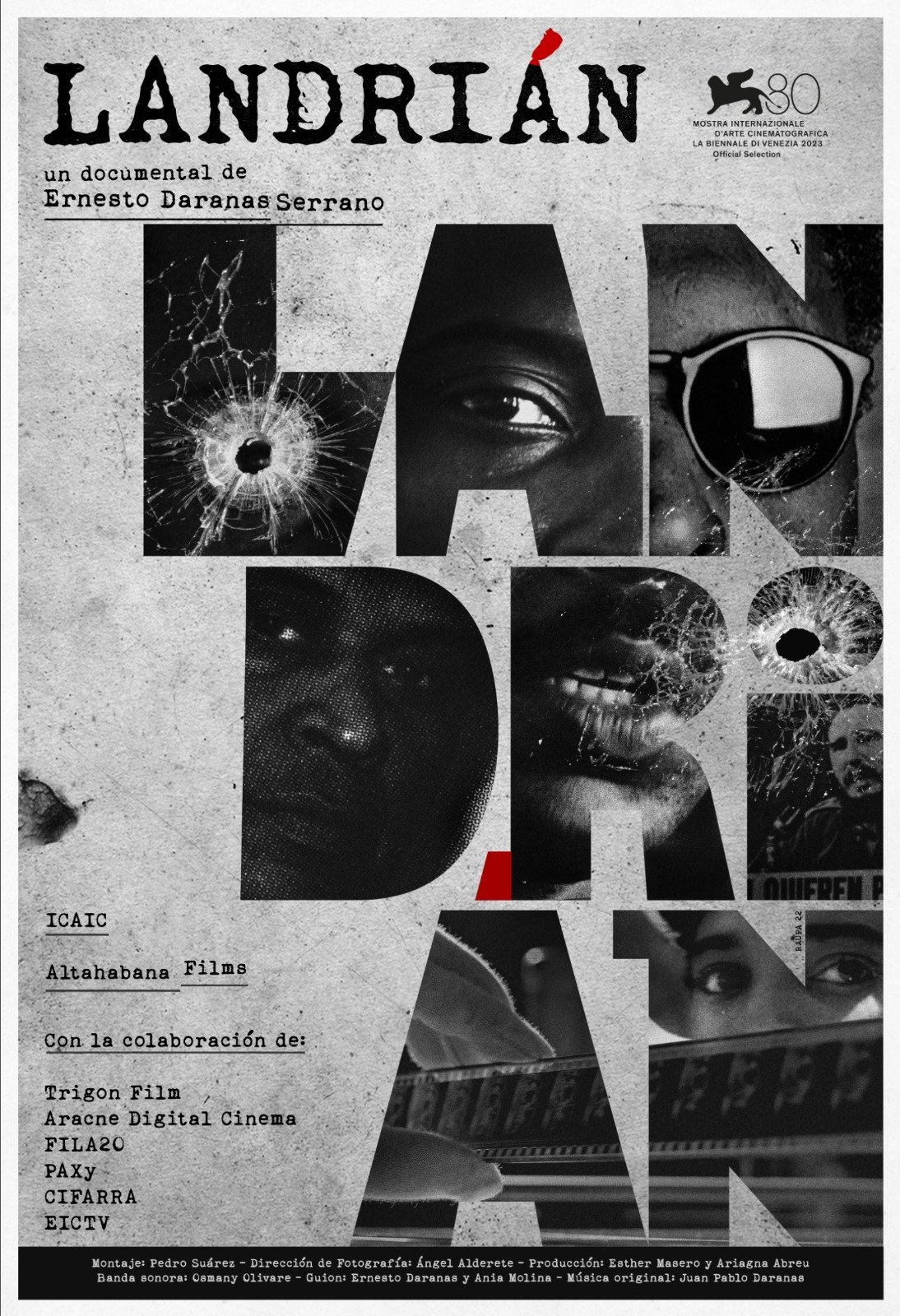

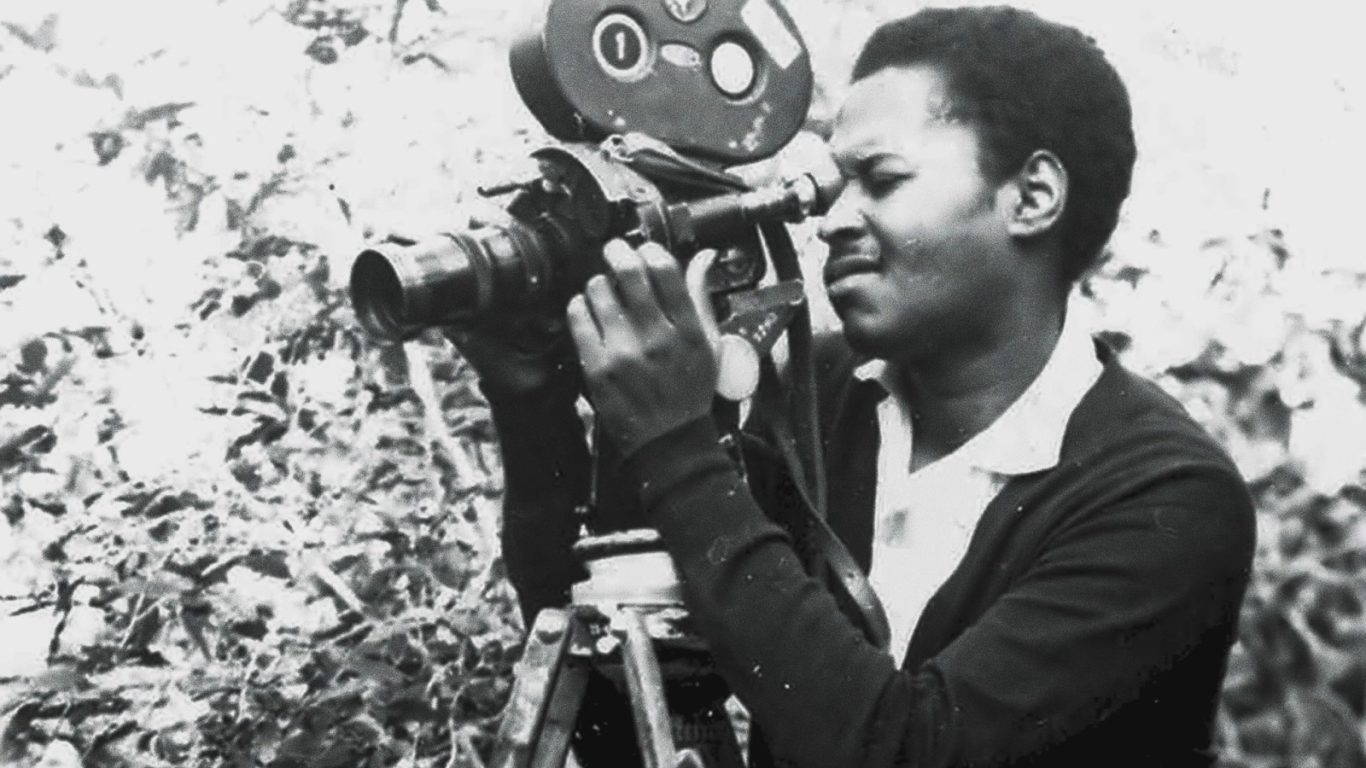

One of the most significant events of this 44th edition of the International New Latin American Film Festival is the premiere of Landrián, a documentary by Ernesto Daranas that aims to bring to the present the life and work of Nicolás Guillén Landrián (Camagüey, 1938-Miami, 2003), the legendary director of Ociel del Toa and Coffea arábiga and one of the pioneers of Cuban cinema of the revolutionary era who, despite his immense creativity and talent, was subjected to censorship, ostracism, prison, and exile.

Until Daranas’ piece was made, little was known about and less had been seen by Landrián. Now, thanks to the dedicated rescue work in the ICAIC film archives, in the year of the twentieth anniversary of his death, a handful of works have managed to be saved that will surely soon be the subject of exhibitions inside and outside Cuba, as well as academic studies.

In the presentation words for Landrián, Daranas dedicated the film to the Assembly of Cuban Filmmakers, stressed that what happened to this director is not even remotely a thing of the past, and reaffirmed “the certainty that a film can change the world, even if it is for 90 minutes.” Referring to the harmful role of censorship and exclusion, he said that “the real problem has never been in our films, but in the reality to which they are due.”

The large audience that gathered this Sunday at the 23 y 12 movie theater rewarded the filmmaking team with a long ovation. Among those attending was Gretel Alfonso, widow of Nicolás Guillén Landrián.

This Monday, Landrián had its second showing within the Festival, this time at noon at the La Rampa movie theater.

Here we collect the statements that Ernesto Daranas gave to OnCuba exclusively.

Nicolás Guillén Landrián is one of the myths of Cuban cinema. The uniqueness of his work, almost all of which has disappeared, and his fast-paced personality, of overflowing creativity, have contributed to this; attractive to some and intolerable to others. In your opinion, what is the weight of Nicolasito in the history of Cuban cinema? Do you think that the interest that the most recent generations of filmmakers now feel will continue to grow?

Landrián is most likely the filmmaker with the greatest influence on Cuban cinema of the 21st century. And it is not just about that morbid fascination that censorship always generates, but about the singularity of his view, between a cinema fundamentally marked by realism and the maelstrom of the first years of the Revolution when several of our most important filmmakers were consecrated. During the fieldwork to prepare the restoration of his films, Enrique Pineda Barnet told me: “In the middle of a stampede towards the future, Landrián was the filmmaker who stopped to think. That’s why they crushed him.” And so it was, at a time when we were not allowed the hint of a doubt, Landrián asked himself: “Where are we going?” Today the answer is visible. That explains part of his validity and why his work continues to be censored.

Will films like En un barrio viejo (1963), Ociel del Toa (1965) and Coffea arábiga (1968) become considered classics of our cinema?

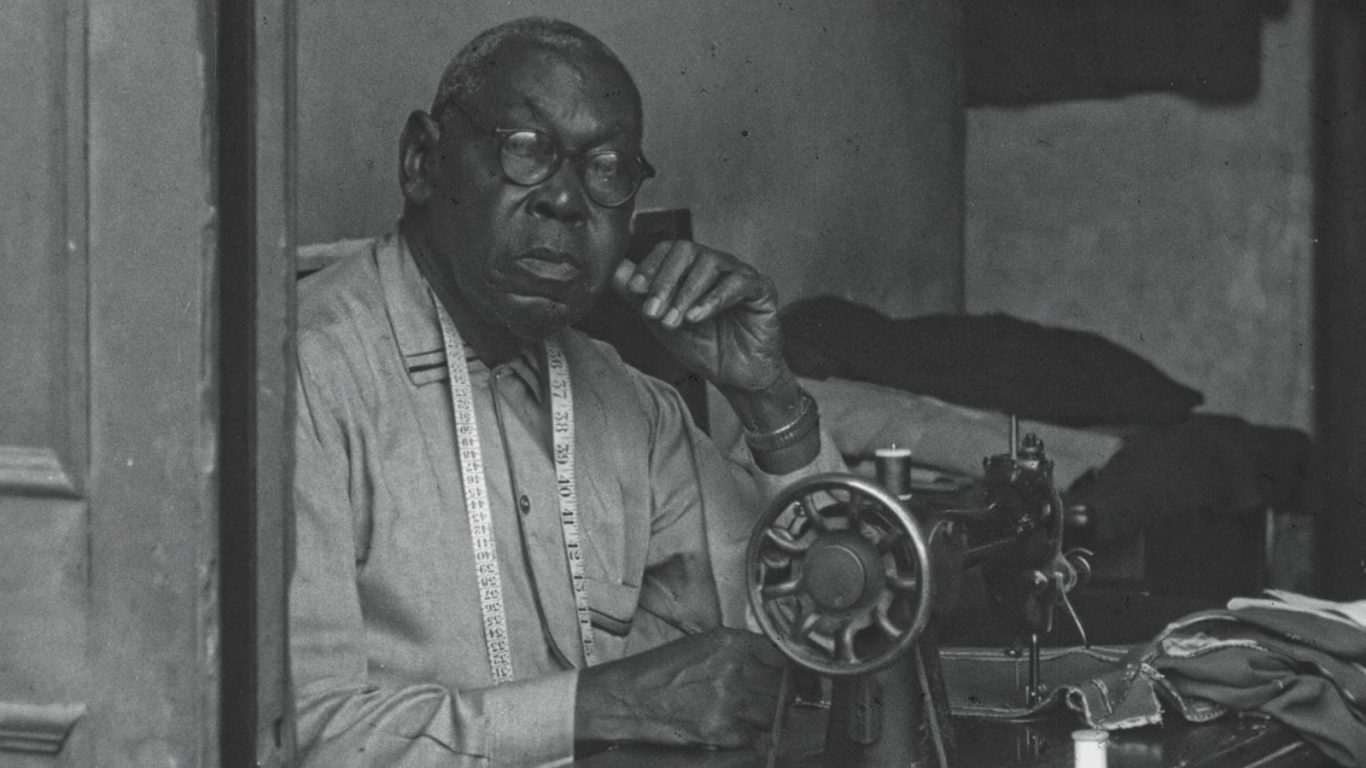

They already are in their own right, and not only for their insight and artistic flight but also for the utmost respect with which [Landrián] knew how to look at us as a people, for the depth with which he scrutinized our gazes, our bewilderment in the face of the turbulence of everything that was happening.

In one way or another, that perspective is present in a good part of the documentary cinema of new generations of filmmakers. That commitment to the individual over the mass, that inquiry into our drama and our self-esteem as a people are some of the identity marks of the new Cuban cinema that dialogue closely with the filmmaker’s legacy.

Is Landrián the result of recent discoveries of this author’s mistreated work or was the effort to rescue what time had not yet devoured in the precarious vaults of the ICAIC a dramaturgical requirement of the documentary’s initial budget?

I wasn’t planning to make this film. My initial objective with the “Landrián Project” was limited to searching and rescuing what I could of his work. It was the loneliness of the pandemic and the very persistence of censorship that moved me to make this documentary. Gretel Alfonso, Landrián’s widow, and Livio Delgado, the photographer of several of his films, were part of that restoration work and it seemed to us that their testimonies had a lot to say not only about the life and work of Landrián, but about Cuban cinema’s present itself in general.

At a time when the Assembly of Cuban Filmmakers is determined to heal its relations with cultural institutions, based on the latter’s abandonment of practices as authoritarian and deep-rooted as censorship, what does it mean to bring Guillén Landrian’s life and work to our days? Do you think it contributes to dialogue between the parties or deepens the rift between them?

I think it helps to understand the futility of censorship. Despite the enormous human and social damage that censorship generates, good art will always prevail against all odds. Although its pretext is almost always political, in reality, censorship is an act of abuse of power, ignorance, and arrogance. As we mentioned in the presentation of the film, history cannot be distorted and rewritten at will. The memory of justice exists and Landrián is the proof.

The Assembly of Filmmakers itself is the expression of the memory of a union. As happens in our people, the Assembly is very diverse, it is made up of filmmakers of all generations, ideologies, and tendencies, regardless of their place of residence. What unites us is a group of common objectives around our cinema that, inevitably, transcend the civic, around that demand for a model of real participation in which leaders and officials are finally understood as the public servants who they truly are. That would be the basis for a truly horizontal dialogue. And, of course, those who understand that such an aspiration is a utopia are not without reason, but we are also not without reason when we assume our right to insist on a form of true participation.

If there was a scale from 1 to 10 to measure emotion, what level did you reach last night when the documentary was shown for the first time before its natural audience, who rewarded it with prolonged applause?

It’s not easy to fill a movie theater with a documentary, and Landrián had a lot to do with that. Of course, I was very happy with the public’s reaction, and I like to think that Landrián felt the same, because to some extent the documentary we made is also a spiritual mass. There are now ten of his films restored that were on the verge of being lost. Many people left the cinema last night wanting to see those movies. That is the most beautiful thing of all, the persistence of art in the face of the futility of censorship.

Was the screening this December 10, at the 23 y 12 movie theater, the world premiere of the work or has it already begun its festival tour? If it is the latter, what impact has it had?

Landrián had its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival. Never before had a documentary of ours been part of the official selection of the oldest film festival in the world. The reaction there was identical to the one you saw last night. Landrián’s vision is absolutely universal and his artistic legacy transcends the impact he has on us.

Although you debuted in cinema as a documentary filmmaker, you are best known for three fiction feature films, in my opinion, of excellent quality: Los dioses rotos (2009), Conducta (2014) and Sergio y Serguei (2016). Do you have more non-fiction projects in the immediate plans? Are you working on a new feature film? Can you tell us something, even if it’s only in the script phase?

I have several fiction projects in progress, but documentaries have once again robbed me of a lot of energy in recent years. It is a genre that I enjoy and that is more feasible in these times of crisis. Among the fiction projects, there is everything from comedies to much more personal and minimalist stories.