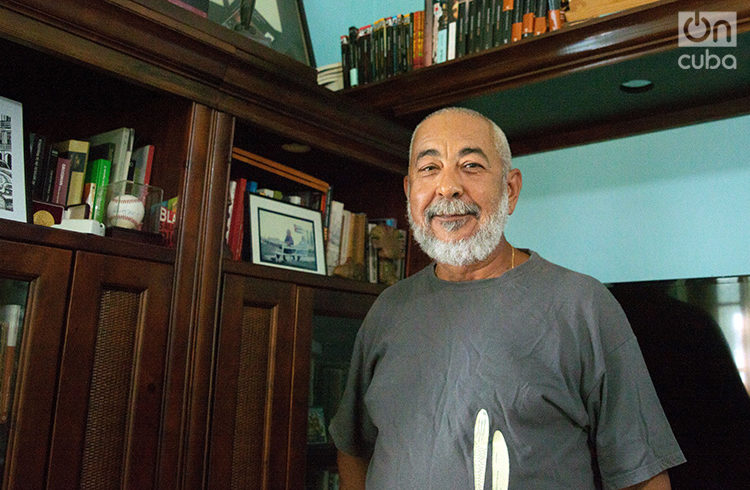

Leonardo Padura Fuentes, probably the contemporary Cuban novelist most read outside Cuba, 2012 National Prize for Literature and Princess of Asturias Letters Award in 2015, recommends those places where not only has he lived his life, but also from where his novel’s characters come from.

Leonardo Padura prepares coffee in a small expresso coffee pot, sweetens it later in a large cup and directly drinks from it. He is standing, in the kitchen in his home. He watches the street through the window over the sink, the former Camino Real del Sur. The street of his entire life.

Leonardo Padura is the journalist, the writer, the one who gave life to Mario Conde, that character that grows and matures with him. But right now he is also someone who has never changed where he lives. He says to me, sitting and resting a bit his wrists on the kitchen table: “Of all the places in Havana, my point of departure, of return, of perspective, of creation, of dreams, of my own personality…is here in Mantilla.”

Alicia Fuentes was 15 years old in 1943. At the time Mantilla was a town between Arroyo Apolo (what today is La Palma) and El Calvario, 12 kilometers to the south of Havana. The Fuentes family came from Cienfuegos and they sent Alicia to stay with her older sister, who lived with her husband in a wooden house by the San Rafael de Arcángel church.

In front of the church was the grocery store where Leonardo Padura father had his small business. Alicia and Leonardo fell in love. They got married five years after their engagement. In 1954, the young couple would build their house. The same one in which we are now talking.

“When I was born, this was a normal barrio. It could have almost all the necessary things: schools, pharmacy, grocery stores, hardware stores, hair-dressing salons, a bus station, two social centers so people could dance…. When you needed something very special you would go to the commercial area of Havana. Here in Mantilla people still say they’re going to Havana when they go to the zone of Monte, Reina, the zone with the large shops.”

There were two principal bus routes that went to the big city: the 4 that went to Havana and the 68 that ended in El Vedado’s Línea Street Tunnel. Both left from the route 4 bus station, a point of reference for the residents of Mantilla.

Leonardo was born one year after the house’s construction. When he turned 10, the Revolution had already triumphed six years before. He was a boy who played baseball in the neighborhood. Every night, at about eight, he would take the canteen with food for his father, who was returning from covering the route as a bus driver. “That bus station was the social and economic center of the barrio’s life. A lot of people from my family worked there.”

He says that in the 1990s the 4 and 68 routes disappeared. One day a big crane came and took down the meter-and-a half high concrete sign that said Route 4, in blue letters. “It’s like the demolition of a memory and a site people felt they belonged to. And those are wounds in the identity, in the sense of belonging of the people.”

There were also the groves. Mantilla was a zone with a great many plots of land dedicated to agriculture, mainly fruits. Mangos, avocados, plums. Padura’s grandfather used to buy the ripe mangoes in the farms and sell them in a small fruit stand or in the only market. It was a very common way of making a living. Until in the name of the famous Havana belt (a failed plan for the cultivation and development of coffee in the 1960s) only a single tree was left to tell the story.

Out of everything that previously existed in Mantilla, the only thing left now is the church. The same one where Padura did his first communion.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the young Padura started expanding his geographical universe. It was the time of the senior high, the Vibora senior high. The time of transition from adolescence to young adulthood.

“It is a place that later became the space for my novels. At some moment I decided that all the cases that Conde received and would resolve would come from his classmates in senior high. In my last novel, La transparencia del tiempo, a senior high classmate goes to see him because someone has stolen his statue of a black Virgin Mary, and from there everything develops.”

For a student, life around the Vibora senior high became very attractive. There was the Alameda movie theater, where premiers were shown and where Padura saw Spartacus, La vida sigue igual and part one of The Godfather. There was the Vibora Coppelita (the small ice cream parlors were called coppelitas after Coppelia, the large ice cream parlor located in the heart of El Vedado); as well as the bookstore.

Padura bought his first books in La Polilla bookstore: Un perro amarillo, La aguja hueca, detective short stories…. Today it is a place dilapidated by time, “impoverished like all Cuban bookstores since the 1990s,” he says.

When the Special Period came, Padura had built a small bachelor’s apartment on top of his parents’ house. His girlfriend Lucía lived in La Palma. But with the ravages that the collapse of the socialist camp had started causing, they understood they couldn’t live apart and they decided to get married.

The apartment became a house in 1998, just as it is today. Even though it is 10 meters from the avenue – the Calzada de Managua – through which the buses, trucks and other vehicles roar, the house maintains a peculiar sound resembling silence. It isn’t absolute silence. Once in a while the plants hanging from the walls, or standing on rails, let certain weak noises drift from outside of Mantilla.

It is the first of the concentric circles of Padura’s universe. Circle and cycle. Where he was born and where he always returns.