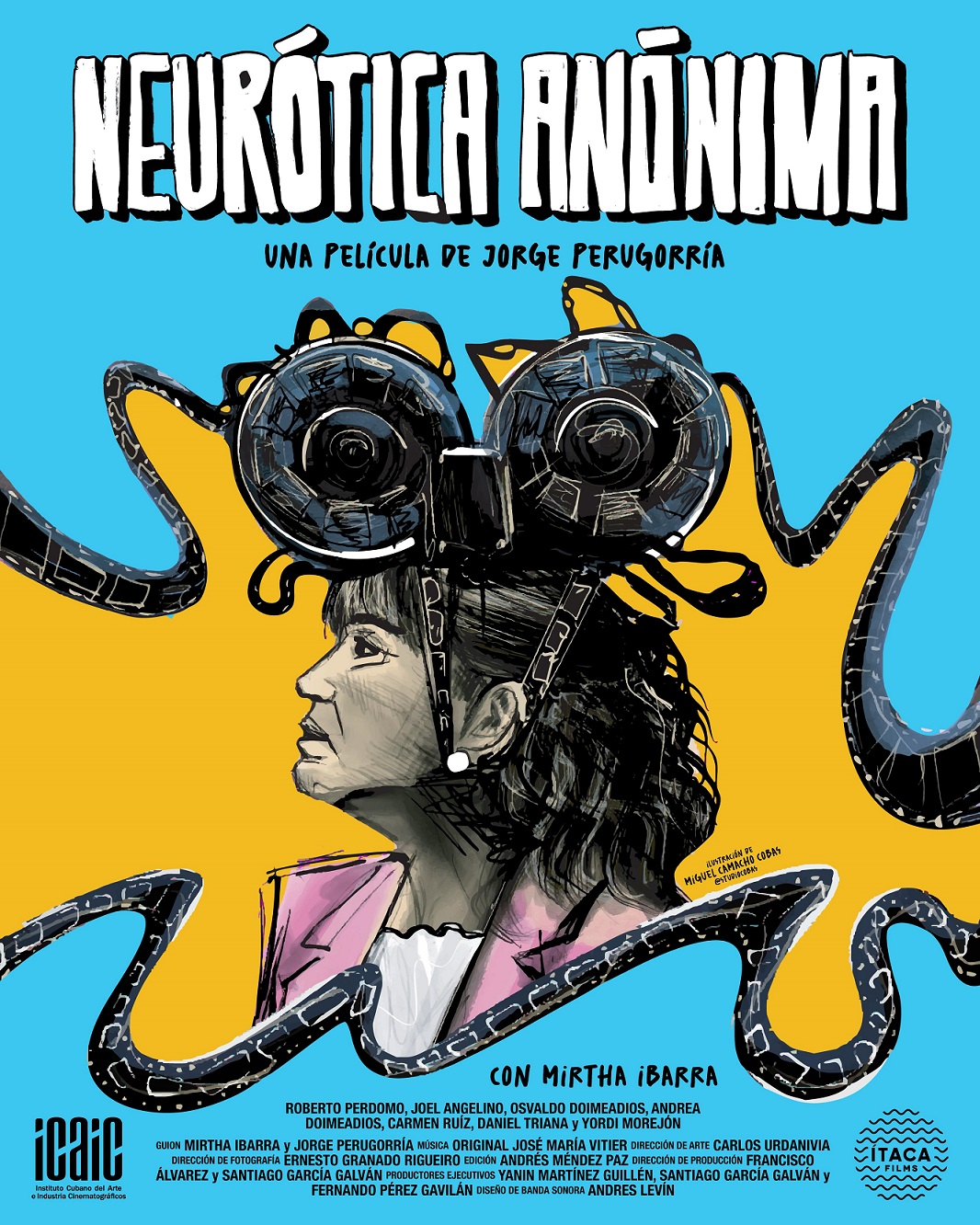

If there was a crowd favorite at the 46th edition of the New Latin American Film Festival, it was Neurótica anónima, the film by Jorge Perugorría starring Mirta Ibarra and Roberto Perdomo. During the three screenings the film had at the festival, attendees filled the theaters and showed enthusiastic approval. They applauded lines of dialogue, images, and even the brief appearance of Mario Limonta in a tiny role.

In short, the film tells the story of Iluminada, a woman who wanted to be an actress and ended up as an usher at the Cuba movie theater, which, due to its dilapidated condition, has been slated for demolition.

Iluminada cannot imagine her life without movies. The hundreds she has seen have alleviated the darkness of her fundamentally frustrated existence. And she is determined not to allow the Cuba theater to be closed.

Amidst all this, she develops a neurotic condition that requires specialized attention. She is treated at an institution where, among other things, they prepare neurotic patients to say goodbye. In a country with such a high rate of emigration as ours, this detail is by no means insignificant.

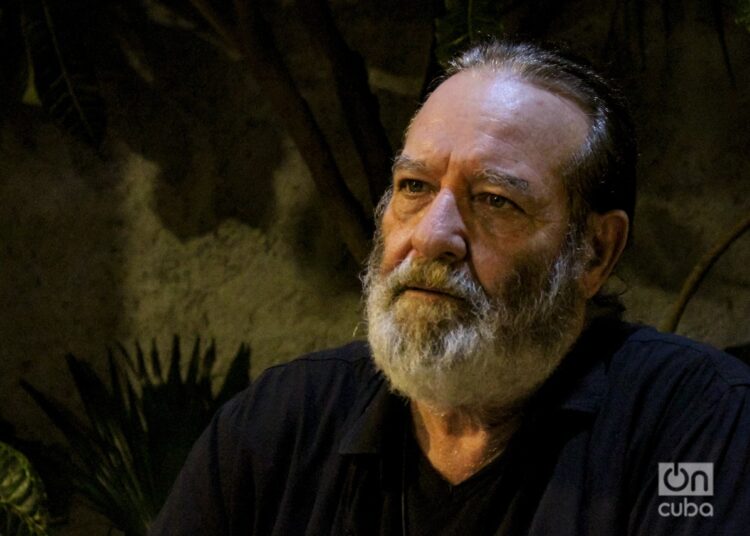

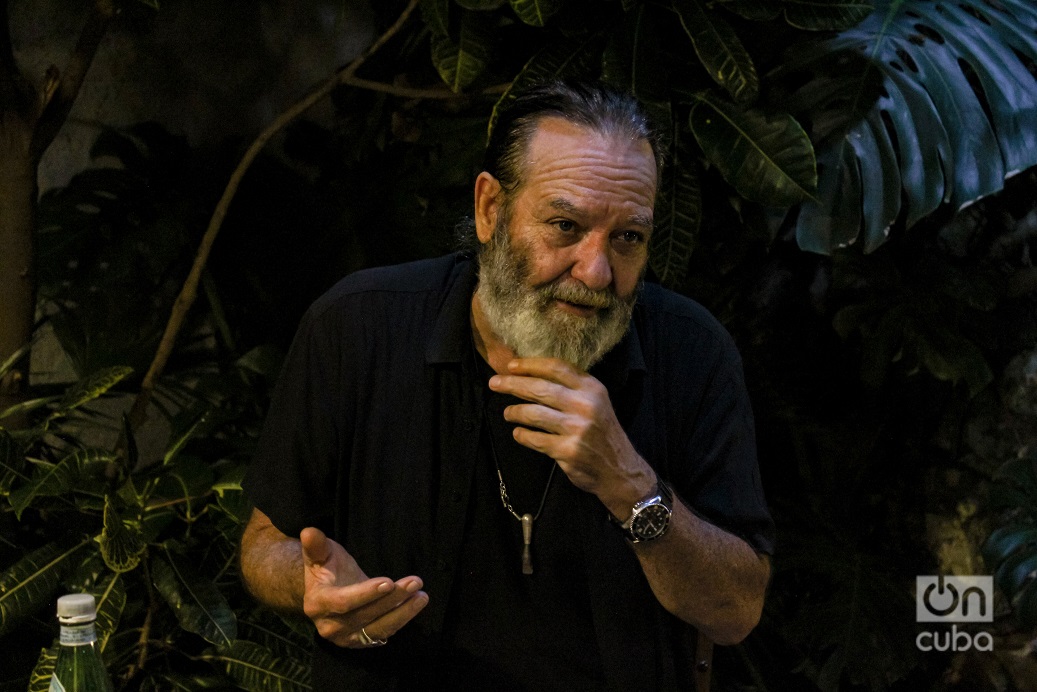

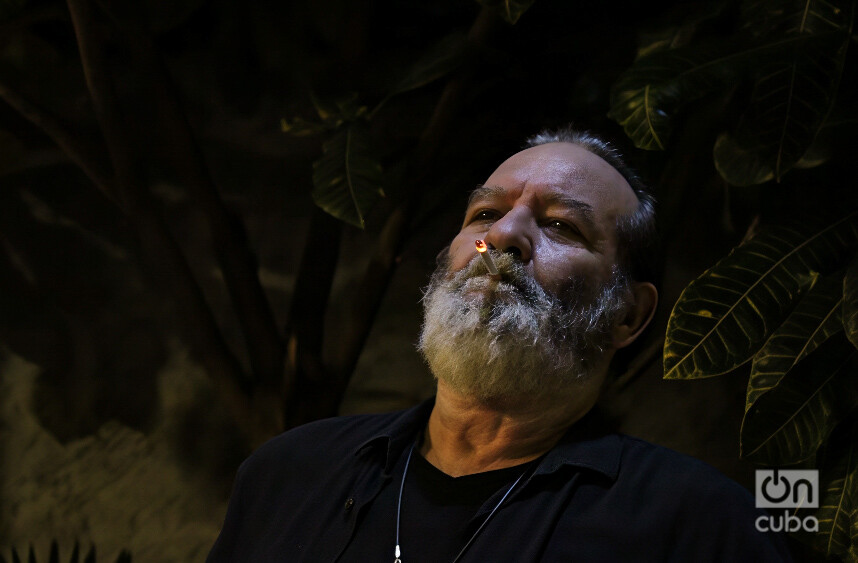

After the Sunday afternoon screening, Perugorría granted OnCuba this exclusive interview. He opened the door of his house to us, where we found a quiet corner perfect for a conversation.

As the reader will recall, Pichi, as his friends call him, has starred in important Cuban films such as Strawberry and Chocolate and Guantanamera. Currently, he is the Cuban actor residing in the country with the greatest international recognition and an impressive list of achievements. Today we will focus solely on his role as a director.

Here is the transcript of our conversation.

All of your work as a director has the country’s current situation as its central theme. Has this happened spontaneously, or are period films more expensive, or perhaps there is a personal connection you have to the here and now as a man and an artist?

That was determined by the same process that led me to get behind the camera, which has been quite organic. I didn’t study to be a director; I never saw myself as a director. It was the circumstances themselves that led me to start making documentaries.

It all started with Habana Abierta. I already knew the group from Spain. They were coming to Cuba, and I thought it would be good to leave a record, to film their reunion with their natural audience. Since I had no experience as a director, I invited Arturo Sotto to participate. We made the documentary and in 2003 we won the Coral Award for Best Documentary at the International New Latin American Film Festival.

From then on, I continued making documentaries, motivated by friends. I liked the ideas, and I filmed again with the same team: Ernesto Granado on photography, Panchito as producer, among others who have accompanied me in the transition to fiction.

Amor crónico (2012), with Cucu Diamantes, is the first feature film I directed alone. It is the first film in the trilogy that is completed by Se vende (2012) and Neurótica anónima (2025). These are films where the concept of film within film is explored, with many influences from Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Juan Carlos Tabío.

Andrés Levín, with Cucu, wanted to do a tour throughout the island after the success of the concert in the Plaza. They proposed that I document the trip. My counter-proposal was to make a film that blended documentary and fiction. I had traveled extensively throughout the country while working in various Cuban films. I used that experience to create not only a documentary about the singer’s tour, but also to incorporate what could be understood as a journey through Cuban cinema, to which I am grateful, and a commitment to our reality.

With Se vende it was the same. They proposed that I make a short film, which I ended up turning into a feature film, with references to the films of Titón and Tabío, Death of a Bureaucrat and Se permuta. And Neurótica…, which has references to world cinema.

Mirta Ibarra told me that she had written a play, and that from it she had developed a first screenplay for film. There was the possibility of making it with ICAIC, and so I accepted her invitation to direct it. I reworked the script and introduced this game of facing mirrors, which is film within film, with a mixture of fiction and documentary, with our reality as the backdrop.

My predilection for addressing themes of contemporary Cuba comes from the directors I have worked with as an actor: Tabío, Titón, Humberto Solás. Dealing with Cuban reality is a commitment for me. The films I have enjoyed making the most are those that have received the most recognition and gratitude from the Cuban audiences. Our audience is always waiting for these movies, so that very rewarding complicity is established with the Cuban viewer.

We increasingly need to make socially conscious films that question reality. This applies to Cuba, but also to all of Latin America.

During the time I worked at ICAIC, we compiled a dossier on each Cuban film that premiered. It was a study to provide directors, producers and distributors with sufficient information about what had happened in the weeks following the premiere. How the audience had received it, what the critics had said, which age group the film in question had satisfied the most. When asked why they liked Cuban cinema, the respondents answered that it was because they saw themselves reflected on the screen, because they recognized themselves in the films. How much does cinema contribute to the construction of identity?

It’s a fundamental contribution. I was born and raised within this film festival. My vision of the countries of our cultural universe was shaped by the films I saw. I traveled through those countries through film, I learned about their idiosyncrasies, their different landscapes…. In fact, this has ended up shaping my professional commitment to Latin America.

Both documentary and fiction films in Cuba have had a very strong commitment to reality. Fiction directors were basically trained within the documentary genre, directly reflecting the pulse of the country. Then, those characters and events were told from another perspective, with other artistic resources, but without losing the connection to national events.

And all of this led the viewer to forge a relationship of complicity with their cinema. It was common to hear the phrase “I love Cuban cinema,” which didn’t refer to a particular work, but to a characteristic way of filmmaking and a commitment to social criticism. The characters in Cuban films were ordinary people, like those sitting in the audience, with a psychology, a use of language, gestures and humor that were common. Complete identification was achieved.

That, like other things, is now at risk, because we are making less and less films. There is no longer that production — up to eight films a year — that allowed for a wide range of national cinema: comedies, dramas, auteur films, more esoteric films, everything that contributed to the exploration of reality in its particularities and to the creation of its artistic reflection.

Rescuing the film industry in Cuba is a challenge. It’s not about restoring it to what it was. We are in a different time; we have to reinvent ourselves. It’s a struggle to rescue and safeguard our identity.

Several generations of Cubans received their audiovisual education at the 46 editions of the Festival. Islanders after all, behind an iron curtain, we went to the movies to see what others were like and how they lived, with the certainty that what was shown during those feverish days, we would not have another opportunity to see.

That’s how it was. I used to go to the Festival as if looking through a window. We would see four or five films a day. Of course, there were no streaming services or film archives, which gave the screenings a unique and unrepeatable quality.

New technologies have democratized access to cinema. But they have also taken away some of its magic. People used to go to movie theaters as if they were going to a temple: to be in communion, to vibrate with the collective emotion.

Cinema as a genre is not at risk. What has changed is the way we appreciate it. The big platforms are buying some production companies, which means that films will now spend less time in theaters because they will be uploaded online almost immediately.

In the scene where Iluminada is in the movie theater listening to lines from Cuban films, the ringing of a bell can be heard. As you say, the movie theater is a temple. In the testimonies I use, there are those who say they prefer to watch movies at home because they don’t have to go out, which is almost impossible given the difficulty of transportation. This is not an exclusively Cuban phenomenon. It happens everywhere.

The vast majority of films we make in Latin America have a festival run. Few are released commercially in the rest of the world, including our own countries. Some, like Strawberry and Chocolate, which is a benchmark, escape this situation. Festivals have become a refuge for cinema. You go to festivals in Europe, for example, and you are amazed that there are still queues to get into the theaters.

Of course, what motivates viewers is precisely the fact that they know there will be no other way to see those films on a big screen, since they will not be shown commercially.

The New Latin American Film Festival was a sui generis event. A tremendous public success. It took place not only in the movie theaters on 23rd Street, but in many other neighborhood theaters, and even spread to the rest of the country.

This is a very difficult time to hold a festival. Some think it constitutes an unnecessary expense in a dilapidated economy. I, who have organized and continue to organize festivals, tell you that a tremendous effort is required to carry out each edition. Everything gets more expensive every year, all the management mechanisms become more complicated with each edition. But people appreciate having festivals. It’s an incentive for their lives. And those of us who make films and festivals cannot give up. If the continuity is interrupted, there is a risk that the event will never be held again. It’s a fire that’s dying out, but it needs to be constantly stoked. If we give up on cultural events, then it would be a total blackout, and I’m not just referring to electricity.

I’m going to give you the right of reply. You’ve surely been aware of the impact that Neurótica… has had in terms of criticism. The most specific points are: the film’s ability to connect with the audience, the profusion of cinematic references and structural problems that limit the understanding of viewers, who sometimes cannot discern when they are facing the real present of the work, when it is a documentary sequence, and when what they see is happening exclusively in Iluminada’s imagination or memory. What do you think of this?

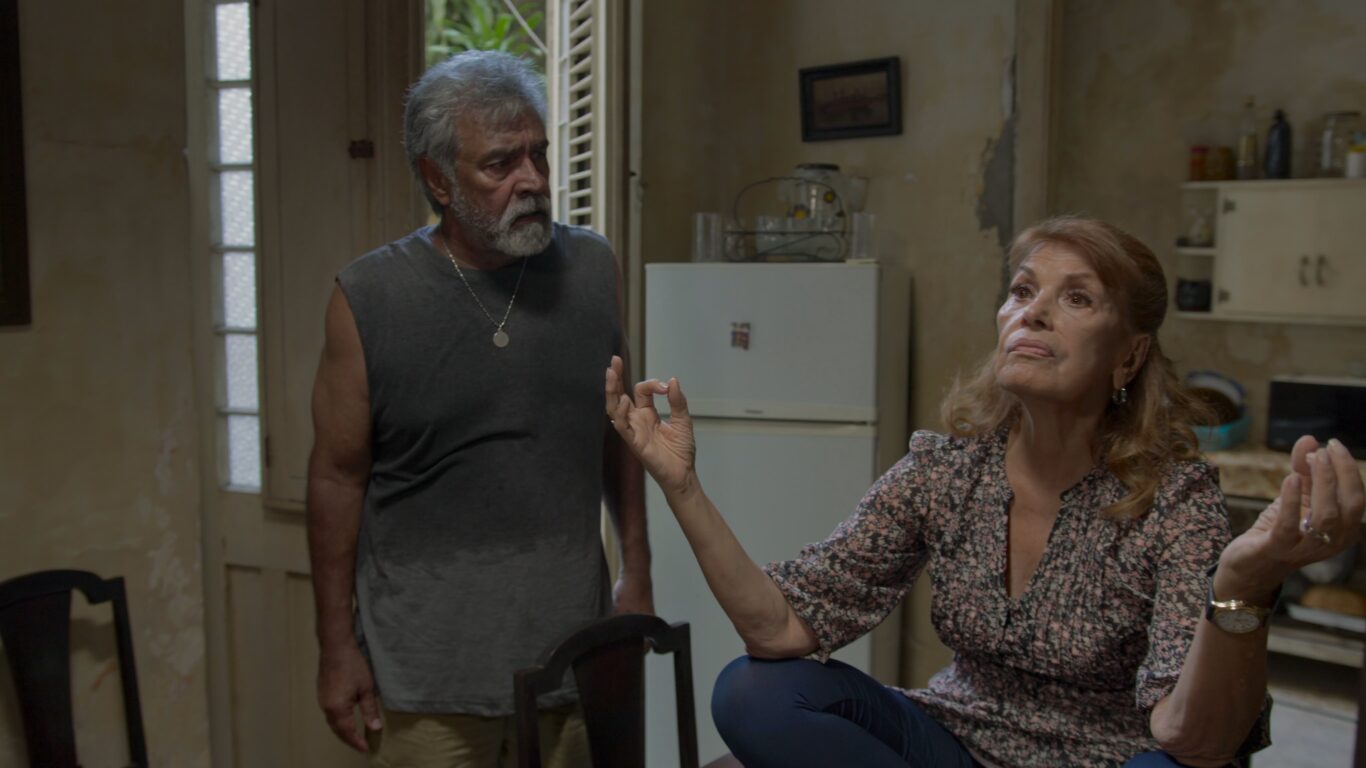

We play extensively with references. Some are more “legible” than others, more obvious. They are part of the neurosis of the character, who has spent a large segment of her life as an usher in a movie theater, and she has seen so much. She cannot live without the movie theater, because it gives her the possibility of escaping her immediate reality, marked by a failed marriage. To make matters worse, there is the threat of the demolition of the Cuba movie theater or, at the very least, that it will be propped up and permanently closed.

There are many ways for Iluminada to connect with films. Sometimes, in front of the television screen, but other times this happens only in her head. When she decides to leave her house, her husband shouts at her to come back, but instead of her name, she hears “Stella, Stella!” which is a very well-known moment from the film A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), by Elia Kazan.

And what if the viewer doesn’t catch the reference?

Nothing happens. Ultimately, it’s an element of estrangement.

Among the films you mention, excluding those in which you participated and which constituted a turning point in your life and work, if indeed the two can be separated, which ones were the most meaningful to you?

I’ll start with Fellini’s Amarcord. Italian Neorealism is precisely a source of inspiration for new Cuban cinema. In the construction of the character played by Mirtha, I looked for iconic moments from film, but I twisted them around to empower her as a woman. In Fellini’s film, there’s a moment when a character shouts “I want a woman!” but Mirtha remembers herself as a young woman, climbing a tree, shouting “I want a man!”

In the film El lado oscuro del corazón (1992), by Eliseo Subiela, the character who jumps into the pit is a woman, but here we throw Iluminada’s alcoholic husband, the character played by Roberto Perdomo, into it.

What the critics are saying is that you went overboard with the references.

I had a lot of fun. I also make films to enjoy myself. Let me give you an example: the scene that mimics the shower scene in Psycho (1960), by Alfred Hitchcock. The shower in Psycho is torrential, we hear the water cascading, but in Old Havana there’s a decades-long drought. In Neurótica… we hear the drops falling. But it’s not just a joke; that scene serves us to talk about machismo, about gender-based violence. Iluminada thinks her husband is going to murder her, but since she’s a woman who lives in and through movies, she imagines the scene like the one in Psycho.

We know that the viewer won’t always understand and appreciate the game. But we hope it works for them as part of the narrative, without necessarily knowing where it comes from.

Another thing the critics object to, as I said, is that the viewer might confuse the different temporal planes. When in the presence of the here and now of the story, when they’re seeing hallucinations or memories of the character, when Iluminada is watching filmed material, when the fiction break away to give way to the documentary….

For me, what you’re listing are forms of expression. The documentary is distinguished by the difference in the treatment of sound and image, in the camera’s movement, which is imperfect.

An allusion to Julio García Espinosa’s theory of imperfect cinema?

Exactly. They are workers who suddenly decide to make a documentary, with no training other than their experiences as viewers.

The film tells its own story. It’s a small film, made with very few resources, in a short time. But that doesn’t justify anything. We wanted to tap into the viewer’s emotional memory. And for them to recover the commitment on our part that they would see themselves reflected on the screen.

What does Benicio del Toro’s cameo mean?

It’s a film made by actors. Mirtha started with the play. I participated in the script and directed it. It’s a strategy to try to save movies, not just the Cuba theater. Some actors have characters, but others don’t, and their mere appearance contributes to our goals. Benicio’s appearance can be seen as a break, something that distances you, that brings you back to the awareness that you are watching a film.

Brechtian alienation?

Yes, that. Filtered through Tabío.

Dolly Back.

Of course.

Do you recognize any point of contact between Neurótica… and The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), by Woody Allen?

I avoided that. It was the first thing we watched when we were doing the pre-production work, to have it as a reference, but, at the same time, to distance ourselves as much as possible from the way that film deals with the game of film within film.

Can it be said that Cuban cinema today is extraterritorial? Is Cuban cinema exclusively that which is made in Cuba, or that which addresses a national theme, or also that which is made by Cubans wherever they are?

Every film that we Cubans make is Cuban. Cuban cinema is being made outside of Cuba. There are more and more Cuban directors, actors and technicians living outside the island. These are people who, of course, want to continue making films.

Cuban cinema needs to open up and embrace this production as its own.

Is it Cuban cinema that needs to open up, or the officials who shape the country’s cultural policy?

Yes, of course. It’s the cultural policy that needs to broaden its perspective. Look at what happened with the centenary of Celia Cruz! It was outrageous! Can anyone in their right mind deny that an important aspect of our national identity is expressed through popular music, and that for decades Celia was the ambassador of Cuban culture throughout the world?

Do you think that capital from Cuban emigrants and capital from Cubans residing on the island could ever be invested in our cinema?

Filmmakers living abroad will continue to fight, more and more, to raise funds for productions that allow them to continue their work.

Ideally, the conditions would be created so that these investments are secure, and that beyond nostalgia or a feeling of belonging to a culture, they can also see participation in our cinema as a business.

The films made in Cuba are generally subsidized. It’s difficult to recoup the investment within the country. You have to think about selling the film abroad.

A cultural phenomenon is occurring. The big orchestras, the singer-songwriters, Van Van, Kelvis, Carlos Varela, have toured Europe to sold-out venues. That could also happen with films. There is a Cuban audience, a Cuban market. If 300,000 Cubans see the film and pay for a ticket, the investment is recouped.

Cuban art has a life outside of Cuba. Also for Cubans.

If a Cuban film in which resources from nationals living in other countries have been invested turns out well, it can be sold to Netflix. The percentage of the profits that corresponds to ICAIC (Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry) is given to them, and the rest goes to the investors. There shouldn’t be any difficulty with that.

In general, is making films complicated?

Filmmaking — directing it, acting in it — in our context, is complicated. In our environment, even more so. As the saying goes, “you suffer but you enjoy it.” We love cinema, and when we’re working, we unleash a beautiful energy, an ecstasy, something that must be very similar to happiness. We do it against all obstacles, against all difficulties; we work twelve, fourteen hours, whatever it takes to move the project forward. That’s the attitude of the entire team that works with me. We are colleagues, but more than that: friends, accomplices.

When we finish, we already want to start again.

Withdrawal symptoms?

Also postpartum depression.