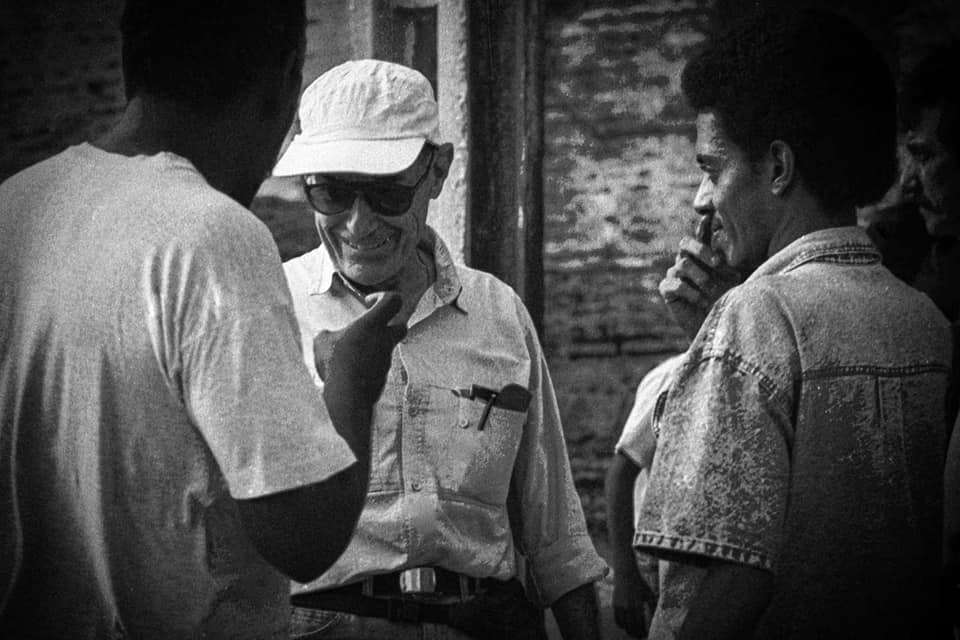

Juan Antonio knows everything about Cuban cinema. Or almost everything: for example, he does not remember the name of each one of the projectionists who have passed through the Yara movie theater since its foundation, nor the price of popcorn in the 1950s, when this imposing installation was called Radiocentro. About everything else, you can ask him.

Between 1993 and 2015 he coordinated the National Workshops on Film Criticism, the most important theoretical event for specialists in the sector. In his curricular synthesis it is stated that the Guía crítica del cine cubano de ficción, of his authorship, “is considered at the moment the most ambitious research on the seventh art on the island, registering for the first time in a volume the silent production, pre-revolutionary and revolutionary talky, including the productions of the creative film clubs, the Film Workshop of the Hermanos Saíz Association, the San Antonio de los Baños International Film School, the Film Studios of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, the Film Studios of Television, among others.” This volume earned him the Literary Critics Award in 2002, an award that he would receive again in 2004 for the book La edad de la herejía; and in 2010, for Otras maneras de pensar el cine cubano.

Juani is a lovable guy, easily accessible and, at the same time, a solid intellectual and a thinker of the national reality. In 2006, the Fundación Carolina de Madrid awarded him one of the prizes it allocates to Latin America to support its research. For his part, the Alejo Carpentier Foundation awarded him the Razón de ser Award for his Tomás Gutiérrez Alea biography project, a text that, perfectionist as he is, he has not finished delivering to the print shop.

Otherwise, Juan Antonio García Borrero (1964) lives and works in Camagüey, his hometown. Between blackouts and lines of many hours, he tries to continue his enormous tasks, convinced that safeguarding the history of Cuban cinema is his mission in life.

What is your professional training?

I have a Law Degree from the University of Camagüey. I graduated in 1987, but I did little practice as a lawyer, since in 1990 I started working at the Provincial Film Center of Camagüey, an institution where I still work. It seems incredible to me that I have remained in the same place for more than thirty years, especially in these times where labor nomadism is becoming more and more natural. Anyway, I have never renounced the career I studied. On the contrary. It has helped me a lot to defend my ideas and what I consider my rights.

How did you discover cinema? How does this become passion, first; and then, field for the exercise of historiography and criticism?

I associate the discovery with my mother, who took me to the Teatro Principal in my city to see the film The Vikings, by Richard Fleischer. I guess there’s a lot of fantasy in that, because before that I had to meet the matinee cartoons at the America movie theater. But the image of my mother accompanying me to see that movie by Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis is recurrent. From then on, I remember everything as if I were living my own life sitting in a movie theater. I remember copying in the notebooks I used in the Máximo Gómez Báez Vocational School the titles of the movies I saw, with the names of the actors and actresses, which I learned by heart. One day I discovered that in the city there was a person named Luciano Castillo, who was in charge of something they called “cinema club,” and who wrote in the newspaper Adelante comments about the films that were projected in the Guerrero movie theater, as part of the cycles programmed by the Cinematheque of Cuba. That was essential for my training, no longer as a cinephile (which I had in my veins), but as someone who is interested in discovering just what is behind what that simple cinephilia does not let us see, because it is just emotion. Every time I have the opportunity I repeat it, because it is my way of showing gratitude: I have had four great teachers in this personal interest in building my own world when approaching the audiovisual phenomenon: Luciano Castillo, who introduced me to the universe of cinema as art; Julio García-Espinosa, who planted in me the vice of rethinking everything based on critical thinking; Ana López, who taught me that, beyond the island, there is a greater Cuba; and Desiderio Navarro, the person who most definitely encouraged me to take seriously the creative use of new technologies for cultural promotion.

What were the movie theaters like in your childhood? Any favorite one?

That question is cruel, because it reminds me that I was born into a world that no longer exists. I could describe what the movie theaters of my childhood were like in the physical order, but “going to the movies” (as my generation did) was much more than sitting in a dark room to enjoy a story. The movies, and this is something studied by the “New Cinema History” and everything that has to do with the “culture of the screen,” were the great pretext for meeting friends and enemies in the same space, and, with the excuse of seeing a movie, fall in love, or show dislike for what we did not like. I feel that we were more “real,” and therefore closer to the real dramas that haunt us as individuals. In Camagüey, at the time I started working at the Provincial Film Center, nine movie theaters were still operating. My favorite was the Guerrero movie theater, because it was where the Cinematheque was programmed and, in general, art and essay cinema. Although going to Casablanca, when a movie was being released, was a real party, especially when the queues reached the other corner, as happened with La Bella del Alhambra, or before with La vida sigue igual, which perhaps is the most box-office film that has been shown in Camagüey.

When did you first participate in the International New Latin American Film Festival? How did you live that experience? Anything in particular that has had a remarkable significance for you?

For those of us who live in the provinces, the International New Latin American Film Festival continues to be something exceptional. Not only because of the films you can see in a unique environment, but also because of the opportunities to exchange with professionals that you would otherwise never be close to. Now I could not specify which was my first festival. Perhaps it coincided with my entry to the Provincial Film Center in Camagüey, as head of the Promotion Department, which allowed me to receive aid for accommodation, transportation, etc. From the beginning the Festival seemed magical to me, but I had not yet had the opportunity to visit other festivals in the world, and discover that with this one in Havana there was something exceptional in terms of public response. A lot of movie theaters where, even with a journalist’s credential, you have to figure out how to get into certain screenings. It was something really extravagant.

You have participated in universities and international congresses with lectures and presentations on Cuban cinema. Is there a real interest in the aesthetic category of our cinema or is the public that attends these events more motivated to learn how life is lived in Cuba?

There is everything. There are people who resort to cinema made by Cubans to get an idea of how life is lived in Cuba. But there is also a remarkable group of scholars who have managed to create a large body of ideas. I remember that at some point I commented that Cuban cinema was much better studied outside Cuba than inside Cuba. In countries like the United States, the United Kingdom and France, for example, you can find a lot of research that, unfortunately, is not yet known or discussed in our country. Today things have changed, and you can already find a vast bibliography within Cuba in which a growing theoretical maturity is revealed, but the debate on the ideas that preceded us remains pending. Above all, the ideas that circulate in the academic circles, which are the ones that originated in these countries that I mentioned to you.

I see that one of your books is titled Cine cubano de los sesenta: mito y realidad. Is it a myth that the 1960s gave rise to some of the most notable films in our history: Las doce sillas (Titón, 1962), Ciclón (Santiago Álvarez, 1963), Hanoi, martes 13 (Santiago Álvarez, 1965), Now (Santiago Álvarez, 1965), Muerte de un burócrata (Titón, 1966), Manuela (Solás, 1966), La hora de los hornos (Santiago Álvarez, 1966), Las Aventuras de Juan Quin Quin (Julio García Espinosa, 1967), Memories of Underdevelopment (Titón, 1968), Lucía (Solás, 1968).… How to explain such a creative explosion in such a short time, when the national cinematography was at the dawn of the industry?

That is precisely one of the paradoxes that I have tried to discuss in that book you mention. The Cuban cinema of the 1960s made by the ICAIC was accompanying one of the political processes that has most impacted the imaginary of that 20th century: the revolution led by Fidel Castro. And it is assumed that when ICAIC was born it had much of an experiment, like the revolution itself. As a result, the documentary school was able to stand out, but not fiction cinema, which only achieved what are still our great classics towards the end of the decade (specifically around 1968): Memories of Underdevelopment, Lucía, Las aventuras de Juan Quin Quin, and La primera carga al machete. Now, insisting on granting the character of a “prodigious decade” to what, by obligation, had to respond to learning, is almost a request for principles where the providential would be explaining the magnitude of what has been achieved. And that does not leave me satisfied, because the approach to cinema is supposed to be multidimensional, and not from idealism and teleology, but from rigorous observation.

Tell us briefly about the Digital Encyclopedia of the Cuban Audiovisual (ENDAC). Its gestation, its ups and downs, its current state. Do you think it could become your life’s work?

The Enciclopedia Digital del Audiovisual Cubano (Digital Encyclopedia of the Cuban Audiovisual), as a platform, is in a good moment. It’s wrong for me to say it, but I think it’s the only place where you can find the same information about silent movies in Cuba, the pre-revolutionary films, the ones made after 1959, inside or outside the island, or information about the movie theaters, publications, the technologies used, socialization spaces such as film clubs or festivals. What is making the difference in terms of ENDAC is the proposal that it makes of what I call “the nation’s audiovisual body,” which would be much more than those stories of “national cinema” that have dominated and continue to dominate up to now. in our studies on the Cuban audiovisual. For me, the “audiovisual body of the nation” is a kind of Borgean Aleph that allows us to bring together, and at the same time radiate, all that infinite diversity of practices associated with the production and consumption of moving pictures linked to Cuba. Personally, it has been a kind of Copernican revolution, insofar as it has allowed me to appreciate this production (with all its modalities) through the transnational approach, articulating the diverse in a single platform that, however, could not be more flexible. While in other places iron borders are being established (ICAIC, Young Cinema, Diaspora Cinema, etc.), here what we want is to abolish that feeling that, to go from one place to another, you have to go through customs, with the cultural police asking for the documentation that identifies you (that is, labels you). On the other hand, the most interesting thing about the ENDAC is that it will always be under permanent construction. I think that more than a database it is a knowledge base. Sure, it will work better to the extent that others contribute to its growth; but, unfortunately, our relationship with the Digital Humanities is still precarious. This is a project that is online thanks to the support of Alex Halkin, director of the Americas Media Initiative, who one day decided to support it, because here in Cuba I never found institutional support, and today I continue to update it independently from Los Coquitos, a community away from the urban center of Camagüey. I wish I could find at some point the support that allows me to dedicate all my strength to it, because, obviously, a project of this type cannot be sustained with good intentions alone.

How does cinema participate in the construction of identity? What is stable and what is mutating in the construction of identity? Can Cuban cinema be compared with Mexican or Argentine cinema, which in the last century contributed to creating national stereotypes that are still used today?

Here I could return to some of the issues that I mentioned in the previous answer. For me, identity is something that is constantly under construction, because there are Cubans who, in the midst of the snow, continue to assume that they belong to that imagined community that we call Cuba. For me, El Super (1979), by León Ichaso and Orlando Jiménez Leal, is as Cuban as Memories of Underdevelopment. And although these filmmakers have had to insert themselves into a foreign context, deal with a language that they do not master at the beginning, and with cultural practices that have nothing to do with their own, they continue to build that Cubanness that I prefer to associate with mystery, instead of offering definitions that impoverish or imprison it conceptually.

Has the Cuban public lost its predilection for its cinema?

I prefer to be cautious when answering that. I would lack scientific tools to prove one thing or the other, but if I let myself be carried away by impressionism, I think not. Although something is real: now the Cuban public does not have greater autonomy to access the cinema they want, and obviously, the audiovisual that Cubans make has very few resources compared to those used by the dominant cinema when it comes to promoting itself.

Are you still working on the biography of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea? Obstacles? Incitements?

I finished a first version that is 800 pages long, but I’m still not satisfied. I never wanted it to be used as a biography, but rather an intellectual biography that allows us to examine the time that Titón lived through, from the most diverse angles. I have published a first part thanks to Oriente publishers, and some fragments on my social networks. But I still haven’t decided to deliver what’s ready.

In the future, will it be possible to fully understand how we Cubans were in these last six decades without dusting off the audiovisual archives produced in the country?

But I would not speak only of six decades. The entire history of that cinema made by Cubans since the cinematographer arrived on the island at the hands of Gabriel Veyre, has been describing how we have been, or how we have wanted to be. Sometimes even by default. It is then necessary to preserve all that set of images and encourage critical thinking that examines them in depth.

How do you imagine yourself ten years from now?

Well, I’ve always considered myself a tragic optimist. That means that every day I wake up with the feeling that I woke up alive by a pure miracle, and immediately, grateful, I start working on what I like, which is writing, especially about Cuban cinema. So, if I get there, I’ll probably be surprised at the same thing: writing. I don’t know where, but what I can’t imagine is doing something else. Of course, there is that old proverb that I like so much: “God laughs at us when he sees us think.”