After playing the blackout Russian roulette in a claustrophobically innocent elevator that whisked us up to the tenth floor, Maestro Guido López-Gavilán del Rosario (Matanzas, 1944) agrees, without obvious enthusiasm, to a photo shoot as a prelude.

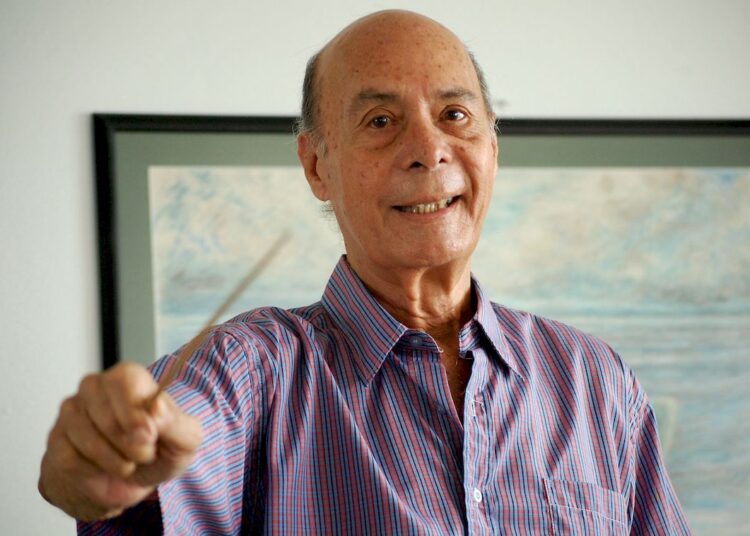

“The faster, the better,” he says calmly once in his apartment, in one of the Vedado towers overlooking the sea. No ships are seen entering or leaving the port—only poachers on their truck tire inner tubes, floating donuts that bring the monotonous seascape to life. Having a picture taken is not in the artist’s comfort zone. Still, his gentlemanly manner drowns out any hint of discomfort, and even a request to fetch a baton for an obliging pose is honored by the octogenarian composer with the alacrity of the solicitous.

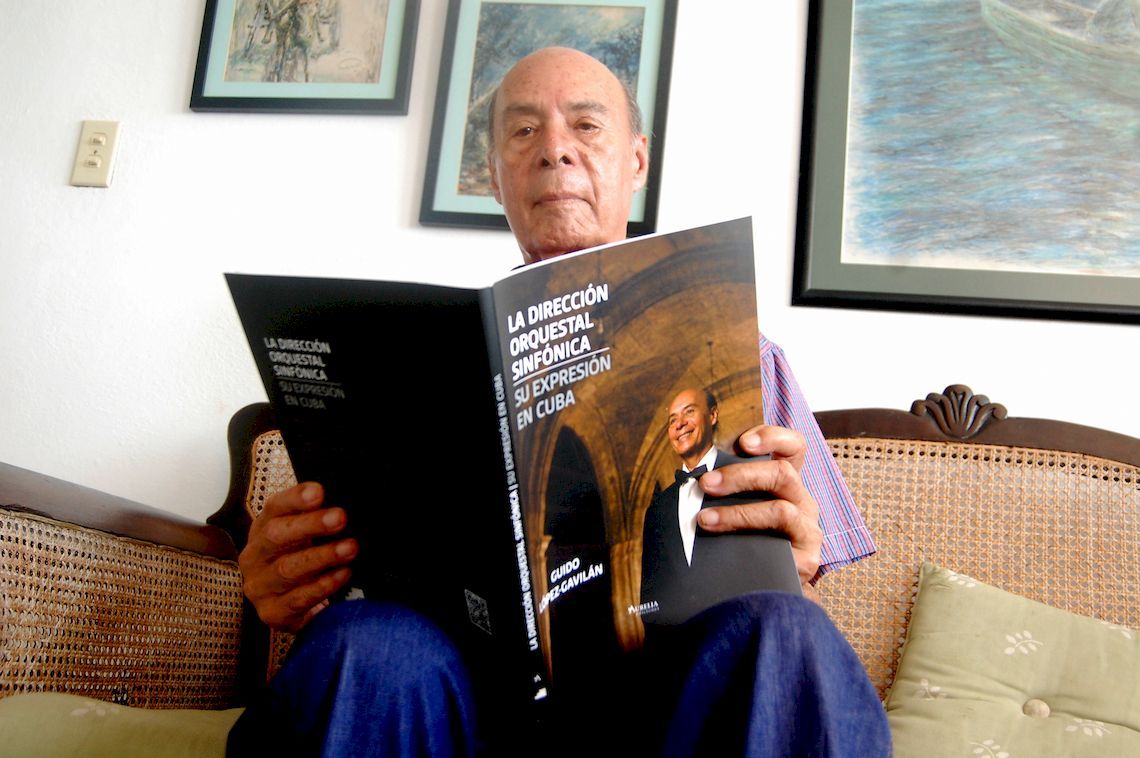

I break the ice. I ask if it’s overwhelming to be the patriarch of a musical dynasty. “No, it’s a great pleasure to see that the seed we sowed continues in the art of music. The family grows, and that makes me very happy,” he replies, then stares fixedly into the camera, sprawled on the colonial-style sofa.

Behind him hang his watercolors and figurative crayons; his Ingres violin when he’s not writing music on the computer.

He’s dedicated this summer to finishing Sueños de sirenas, inspired by Sirènes, the third movement of Claude Debussy’s symphonic triptych Nocturnes. The piece is written for female choir and strings, in the style of the French composer, and is scheduled to premiere in November at Casa de las Américas.

A musical Noah’s Ark

The dynastic aspect is not an exaggeration. Even less so is the patriarchal aspect. The family network begins with Evelio López-Gavilán, founder and director of a Cuban and Latin American music ensemble in Havana. His wife, Nela del Rosario, a television host and graduate of the Municipal Conservatory of Havana, provides a musical and cultural foundation for the lineage.

From that marriage were born two brothers: Evelio, known as Buby to his close friends. A hydraulic engineer, he was a music lover, but “didn’t like making music.” He died in the prime of life: 29 years old. And Guido, musician, composer, and conductor, winner of the 2015 National Music Prize.

He studied at the Amadeo Roldán Conservatory in Havana and the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow. He founded the University of the Arts of Cuba (ISA) and directed its conducting department for more than two decades.

The composer of the symphony Post-Neo-Retro (2020) is a leading figure in the genealogical galaxy, both for the weight of his oeuvre, as vast as it is diverse, and for his teaching work, having trained generations of musicians.

Guido married pianist and pedagogue Teresita Junco (1946-2009), daughter of clarinetist and pedagogue Juan Jorge Junco. From this union were born two musician sons: Ilmar López-Gavilán, a violinist par excellence who emigrated and developed an international career that included conducting the Harlem Quartet and winning a Grammy in 2012; and Aldo López-Gavilán, a pianist and composer renowned for his virtuosity and versatility in classical and jazz music, who studied at conservatories in Havana and the London Academy of Music. Aldo has composed orchestral works and has developed a unique career in Cuba and abroad.

Aldo, in turn, married the conductor and teacher Daiana García, a distinguished student of Guido’s. The couple has twin daughters, Adriana and Andrea López-Gavilán García, who study various instruments (piano, guitar, flute, electric bass, and saxophone), continuing the family tradition.

Ilmar is married to cellist Seoying Yang, with whom he has two children, Leah (pianist) and Ian (violist).

The family also extends to the García branch, with Josué García (Daiana’s brother), a music producer, married to singer Rochy Ameneiro. Their son, Rodrigo García Ameneiro, a pianist and student of Aldo’s, is married to violinist Tania Hasse; together they form the Espiral Duo.

Furthermore, clarinetist and saxophonist Alejandro Calzadilla García, a student of Teresita’s brother, Arnoldo Junco, and Daiana’s nephew, married dancer Yuyú Vega, whose eldest son, Ronny Yunior, is studying piano.

If another flood were to come, the fruits of this family tree would be enough to save music from extinction, cradled in a family Noah’s Ark.

Memories

What was the first instrument you picked up?

The first instrument was the guitar, and also the piano, because my parents were musicians. My mother was a piano teacher and television host, and my father was a musician, playing the guitar from a young age.

From a very young age, I remember my father rehearsing at home with trios and quartets. My mother studied piano, and both of them encouraged me to play. I liked music and started studying the guitar with my father.

How old were you when you started playing?

I don’t remember exactly, but I must have been around 7 or 8.

Was it in Matanzas or already in Havana?

In Havana. I was born in Matanzas because my family is from there, but we were already living in Havana when I was born. My mother went to Matanzas to be with my grandmother during the birth.

I’ve lived in Havana the whole time, but I’ve always had a close connection to Matanzas because the rest of my family remained there. We went there every weekend, and I spent the holidays at my grandmother’s house. Later, I conducted the Matanzas Symphony Orchestra for a few years, sharing the same time with Havana.

Matanzas is a city very dear to me, as is Havana.

The violin

What was your initial musical training like?

I began studying music at home with my parents. Then, as a young man, I entered the Amadeo Roldán Conservatory to study violin.

Why did you choose the violin?

I liked the instrument, its timbre, and the way it sounded. I decided on the violin, although at that time, music wasn’t studied professionally from the beginning as it is now, but rather was more of a vocation.

Although my parents taught me music, they never encouraged me to become a professional musician; they thought I would be an engineer or architect because I liked math and drawing. They rightly thought that music was a very difficult field to break into before the Revolution.

What finally led you to pursue music professionally?

As a young man, I decided I really liked music and, after the Revolution, the possibility of making a living as a musician opened up. That was around 1962, after the literacy campaign. I was in the Sierra Maestra as a volunteer teacher between 1960 and 1962. During that time, I had to abandon my musical studies, but then I fully immersed myself in the world of music.

Choral music and Isaac Nicola

According to your biography, you graduated with a degree in choral conducting at the age of 22. Was it a choice you made, or was it your own doing?

It was a choice. At the Conservatory, there was a choir directed by Manuel Ochoa, which I really liked. From the moment I began singing in a choir, I was drawn to the possibility of performing large collective works and popular songs together. Ochoa started the first choral school in Cuba, where I studied choral conducting and training to become a choral singer.

When the choral school opened, I enrolled in choral conducting, although I continued studying violin (at that time, it was possible to study several subjects at once). Isaac Nicola, director of the Conservatory, was very supportive and helped me organize a special curriculum that included violin, choral conducting, and complementary subjects such as harmony, counterpoint, music history, analysis of musical forms, and orchestration.

How do you remember that time at the Conservatory?

It was a very beautiful time, of which I have fond memories. I made great friends with colleagues like Digna Guerra, Frank Fernández, Teresita Junco (who was my wife), Carmen Collado, Gonzalo Romeu and Ninowska Fernández-Brito.

A very talented generation…

It was a rather special generation, with great potential for musical development. Initiatives for young people were created, such as the Hermanos Saíz Brigade, which allowed us to organize our own activities and encourage the development of young composers and instrumentalists.

“Los Chichirichis”

Did you have your own musical group?

Yes, we had a vocal quartet, although we did it as a hobby. We sang in nightclubs, and it was Teresita, Digna, Frank, and me. We sang newly released songs by [César] Portillo de la Luz, José Antonio Méndez, from the feeling era.

What instruments did you play and what was your role in the quartet?

I played the violin, the piano (as a complementary instrument, although I was never a pianist), the guitar and, in the quartet, I sang and played guitar at times.

And did you go by any name?

We called ourselves “Los Chichirichis,” although it was an informal name [laughs].

From “Los Chichirichis” to Beethoven

Despite being under siege, under political and military stress, in the 1960s, Cuba still retained the inertial bohemian vibe of the 1950s, especially in Havana. While Guido enjoyed the festive atmosphere and seductive nightlife, he expanded his portfolio of choral works.

His famous piece El Guayaboso (1967) is from this period, but a few years earlier, in 1964, he composed the works Si compartimos and Nubes, both for female and children’s choirs. At the same time, his interest in the musicality of García Lorca’s poetry led him to compose Canción cantada and Media Luna, both from 1965, written for voice and piano and premiered in the Cuban capital in 1968.

The following decade saw the appearance of Sinfonía urbana (1975) for mixed choir, narrator and instrumental ensemble; De cámara traigo un son (1977) for string orchestra, and Tramas (1979), premiered in 1981.

The crowning achievement of that era was the performance, for the first time during the socialist period, of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

“It was quite an event in 1979. I conducted the orchestra and Digna organized the choir, which was mixed, with more than a hundred people, including established choirs and people who wanted to learn. It was a very beautiful social project. And the singing was in German.”

Maestros, Moscow, the snow

The maestros López-Gavilán had seemed to embody the essence of Cuban and Slavic music: José Ardévol, of Spanish origin; Leo Brouwer, Harold Gramatges, Edgardo Martín, Manuel Ochoa and the Bulgarian violinist Radoviev Modaliev, a disciple of Georges Enescu in Paris. All of these names remain etched in the composer’s memory as unique opportunities for knowledge, experiences and mentorship, fleeting but cherished.

From choral conducting, López-Gavilán moved on to orchestral conducting. Here in Cuba, his specialty professor was Daniel Tulin, a Soviet who worked with the National Symphony Orchestra and trained young conductors on the island.

This praxis prepared him for a scholarship to the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, where he studied orchestral conducting with Leo Ginzburg, one of the titans of the Soviet academy who trained a generation of important conductors, including Michail Jurowski, Nikolai Korndorf, Fuat Mansurov, and Vladimir Fedoseyev, as well as the Chinese conductor Cao Peng.

What was your experience in the Soviet Union like?

It was a tremendous experience that marked my life. At the conservatory, I met great artists like Rostropovich and Richter, and distinguished students like Gidon Kremer and Dmitri Kitayenko.

The level was extremely high, and soloists and orchestras from all over the world were constantly touring. I was able to see orchestras from New York, London, Paris, Vienna, and Leipzig, as well as all those from the socialist camp.

It was a very rich musical scene that opened the horizon to work at the highest level.

The Soviet school of the 1970s, although formidable in technical rigor, was reluctant to open up, to assimilate the Western European avant-garde…

In reality, they weren’t very inclined toward the avant-garde. There were countries like Poland or Romania that were more open to experimental music. In the Soviet Union, although it wasn’t prohibited, that type of music wasn’t much promoted.

The music that was composed was more prone to following traditions, with a very high level, but it wasn’t avant-garde like the Polish composer Penderecki. Shostakovich and Prokofiev were first-rate, but not experimental avant-garde.

I’m thinking of the music of Khachaturian, for example, with a rather nationalist bent, right?

Yes, he was nationalistic and conservative in his approach, especially compared to the avant-garde.

However, in other countries of the former socialist bloc, there was a very marked movement for musical renewal.

If I ask you to close your eyes and think of Moscow, what memory comes to mind right now?

Many memories come back, but obviously, the snow.

One very vivid, almost cinematic, memory was the first time I saw Saint Basil’s Cathedral. I was walking with Frank [Fernández] in front of the museum, in front of the Kremlin, and suddenly, between two alleys, the image of the cathedral with its incomparable domes appeared. It was a very special moment for me.

And the snow, which I will never forget.

***

Thus, in Guido López-Gavilán’s story, music is not just sound; it is history, culture, memory and emotion. A sudden journey from Havana to Moscow, in the middle of a scorching summer, from tradition to the frontiers of the possible, narrated with the intensity and color that only a maestro, in a give-and-take between his sensitivity and his memories, can offer.

Formats and creative process

For the author of Cantos de Orishas (2000), working with the widest range of formats seems to be a necessity of his intense curiosity and experimentation, which ranges from symphony orchestras to a single instrument — which can be the guitar, piano, double bass, or harp, among others — to unorthodox instrumental combinations for quartets.

Now, turning to the creative process, you have a vast catalog of different formats and genres. How do you choose the format for each work?

Generally, I first think about the general idea of the work and the format I want: chamber music, choral, or symphonic. I make a plan where I save ideas about the type of music I want to hear. Then, I develop those musical ideas, previously on the piano and now on the computer, and the work takes shape from those preconceived ideas.

Do the musical ideas emerge per se, or do you take elements from reality and bring them to the musical level?

It depends. For example, with the famous Guaguancó, I set out to bring a rumba to the level of chamber music, for a string orchestra. I took real elements of the rumba and developed them in that format. In other works, like Cantos de Orishas, I appropriated those songs to create a musical work.

I also have works like the Sinfonía Neo-Post-Retro, which is a tribute to the great 20th-century symphonists, where the ideas are my own, but inspired by that style. I draw heavily on Cuban music and its traditions, although there are also works conceived solely in musical terms and with specific effects.

And how do you handle commissioned music, where there’s a forced lead or someone else’s expectation?

I just finished a string quartet commissioned by the United States. They didn’t ask for a specific type of music, but they suggested something with a Cuban nature. I took musical ideas related to our music — rumba, mambo, son — and brought them to the quartet, creating my own motifs that are coordinated between the instruments. In this way, I fulfill expectations, but based on my own language.

***

The art of composition, believes the author of ¡Qué Rico E’! (mambo, 1996, for mixed choir), is a delicate balance between respect for tradition and the audacity of innovation.

When he addresses Cuban themes imbued with a strong Afro-Cuban or African influence, he acknowledges that the most difficult part is “deciding which elements to retain and which to stylize,” without falling into the trap of overly Westernizing the piece.

For the composer, the great secret lies in wise selection, in maintaining a recognizable identity — as in his work Guaguancó — but also in contributing a personal vision. Sometimes, in this process, he consults his children, although each one moves in a different musical universe; for example, Aldo is more focused on jazz, a parallel world that enriches his own perspective.

Regarding the distance between the conceived musical idea and the final result, he says: “Fortunately, what I imagine usually coincides with what sounds”; therefore, he doesn’t feel betrayed by himself. This correspondence, he believes, is the fruit of talent and accumulated experience, although he admits that there are always unknowns when experimenting with new procedures, but in his case, reality generally faithfully reflects the initial vision.

Empathy, batons and the role of the conductor: leadership or pantomime?

Regarding the technical difficulty of his compositions, he has never felt that his ideas exceed the capabilities of the performers, as he always thinks about the practical execution of the work. As a conductor, he understands the challenge of premiering a piece and strives to make the difficulties manageable, helping to find solutions to make the piece work. He contrasts this attitude with that of other composers who, he says, are less concerned and leave the burden of resolving technical problems to the performer.

López-Gavilán has accumulated sophisticated experience conducting orchestras. Already in his mature years, in 1995, he founded the group he leads to this day, the chamber orchestra Música Eterna.

He admits that the question of whether the conductor truly conducts or if it’s just a pantomime is common in the average audience’s perception. However, he firmly asserts that “the conductor does conduct,” although communication depends greatly on the orchestra’s professional level.

In more experienced groups, the subtlety of gestures translates into the sound, and a pronounced or delicate accent is reflected in the performance. In well-known works, the conductor has greater influence on the final version; in premieres, the musicians are more focused on their scores, which makes handling difficult, but communication is always present.

And regarding the use of the baton? It all depends on the conductor and the music. “The baton helps to specify the rhythm and accentuations, but it’s not essential,” he asserts. For slow, melodic pieces, he prefers to conduct with his hands alone, while for rhythmic or technically complex music, the baton is more useful. He sometimes alternates between the two, depending on the nature of the work.

Accidents and pirouettes: reality as a surprise

In his long career, he has never witnessed a musician faint during a concert, although he has experienced accidents unimaginable in the most unbridled probability.

He recalled an episode in the former Yugoslavian city of Zagreb, now the capital of Croatia, when he was conducting Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and the oboe made a mistake. To prevent the orchestra from becoming disorganized and disrupting orchestral coherence, he made a very pronounced, almost violent, gesture with the baton, which broke and injured his hand. Despite the blood, he managed to maintain control and successfully complete the concert, his tailcoat splattered in red.

He also recalls an anecdote from a Cuban province with violinist Alfredo Muñoz, whose bow caught on the baton and flew off, but Muñoz masterfully caught it, turning the incident into a kind of improvised choreographic act between the two.

A symphonic reggaeton?

When I asked him if he would compose a symphonic reggaeton, López-Gavilán, smiling, honestly replied that it would be impossible for him, although he acknowledges that others could do it.

Regarding the prominence of the instruments in a work, he explains that it is determined by the music and the score. The prominence shifts from one instrument to another depending on the melody and the desired effect, and although the conductor may emphasize certain instrumental families, it essentially all depends on the composer.

Sacred or secular music?

Regarding his favorite composers in choral music, he confesses that he doesn’t have one in particular; he prefers to immerse himself in the expressive world of each composer he performs. He recognizes the greatness of universal figures such as Beethoven, Brahms, and Stravinsky, but his focus is always on the present, the work at hand. Regarding genres, he values both sacred and secular music, each with its own historical function and beauty.

At the same time, he shows no preference for specific contemporary composers in choral music, as his listening is broad and general.

Bossa nova, Mercedes Sosa, Villena’s poetry, La Pietà

In his free time, Guido López-Gavilán often listens to music related to his immediate work, but he also enjoys Brazilian popular music, especially bossa nova and traditional Latin American music, highlighting the Argentinean Mercedes Sosa as an exceptional singer.

Regarding the influence of literature or film on his music, he admits that it hasn’t been very frequent. However, he mentions that he has worked on pieces based on literary texts, such as Sinfonía urbana, inspired by a poem by Rubén Martínez Villena, where the music should evoke poetic images. He was also struck by seeing Michelangelo’s sculpture La Pietà in the Vatican, which he attempted to translate into sound, although such inspirations are rare in his work.

His vocation for teaching, which was born at a very young age, when he was one of the first volunteer teachers in the literacy campaign in the Sierra Maestra, remains intact. Since then, teaching has been a constant in his life, and he plans to continue teaching as long as he can, because he considers education a duty and a valuable contribution to society. His students and alumni adore him.

Free zone

Tea or coffee?

Coffee.

Do you see yourself in the mirror of Capricorn, responsible and hardworking?

I think those are valid traditions to the extent that one believes them.

Do you believe in the music of the ancient spheres?

Not exactly. Music exists everywhere and will always exist as long as there is humanity, emerging from the entire universe.

Do you prefer fried plantain or plantain chips?

Both.

Do you have an alter ego in music?

Not that I know of.

Rum or beer?

Both.

The Amadeo Roldán Auditorium…

An irreplaceable loss.

Bach or Mozart?

Both.

How would you briefly describe Maestro Electo Silva?

Unique and original. Electo, his name says it all.

Do you remember the last book you were reading?

I’m rereading El Imperio de La Habana: la mafia en Cuba by Cirules.

Beethoven or Tchaikovsky?

Both.

Baton in hand… Karajan or Dudamel?

I can’t choose.

Albert Einstein said that if he weren’t a physicist, he would have been a musician. If you weren’t a musician, what would you have been?

I would have liked to be a painter.

What technique do you use in your paintings?

Crayon and watercolors. Watercolors are difficult because water isn’t easy to control.

Leaving aside any possible religious affiliation, atheism, or agnosticism, which of these statements do you prefer? God existed, God doesn’t exist, God will exist.

God will exist. Humanity needs to believe in something that supports it. The gods will exist as long as humanity exists.

How would you like to be remembered in the future?

Being remembered is enough.

Thinking about the blackouts, how many steps are there from the entrance to your tenth-floor apartment?

More than I’d like.

Is music a mystery or a mathematical equation?

A mysterious equation.

If you were on a desert island and could send a message in a bottle, what would you write?

“Be happy, because I’m already gone.” [Laughs]

Who do you owe more to: Cervantes or Saumell?

Equally to both.

Have you thought of an epitaph?

Not at all.

Finally, an exercise in verbal economy and emotional spontaneity. How would you describe Cuba with a four-letter word?

Love… Yes, love.