The day before singing in a packed micro-stadium — two performances, Friday and Saturday, at Montevideo’s Antel Arena, with seats sold out for months — Silvio Rodríguez chose the dirt road to Rincón del Cerro.

Thirteen years after his last visit to Uruguay, before reuniting with thousands of people every night, the singer-songwriter wanted to knock on another door: that of the humble farm of José “Pepe” Mujica and his partner in life and struggle, Lucía Topolansky. He wanted to go see her.

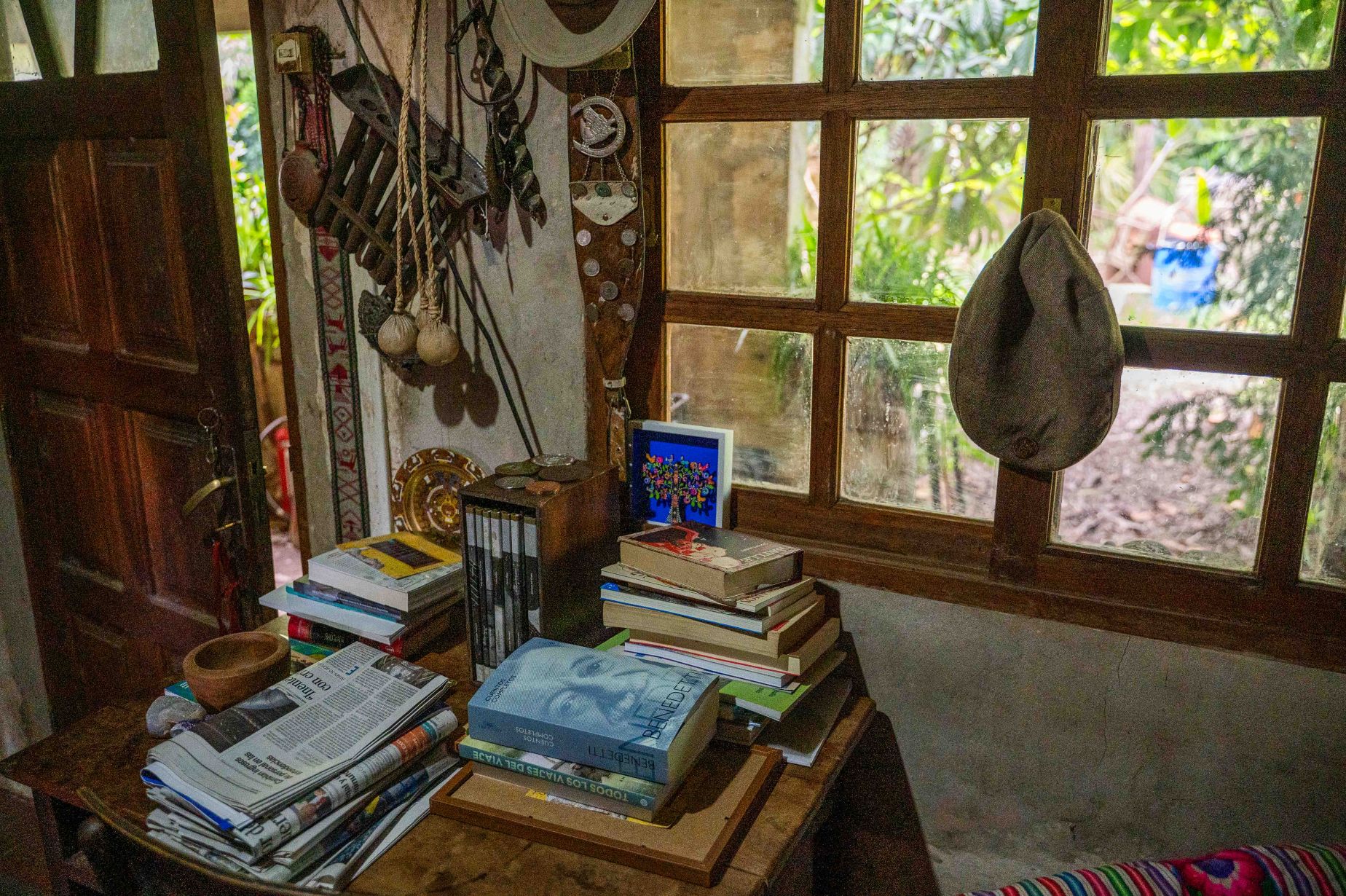

The house, famous for all that was denied to an ostentatious life, still retains the breath of its occupant. Newspaper headlines and newscasts often presented Mujica as “the poorest president in the world,” although he rejected that label. He said he was a “sober” president, who needed little to live.

“I live the way I lived long before I was president,” he explained in a 2014 interview. “I still live in the same neighborhood, in the same way. I am a republican president. I live the way most of my people live.” It wasn’t posturing or marketing: it was his way of inhabiting the world.

The former Uruguayan president, who spent thirteen years in prison between 1972 and 1985, bought his farm as soon as he was released. A fourteen-hectare estate on the outskirts of the Uruguayan capital, surrounded by nature, animals and love.

There, alongside Lucía, he tilled the land and cultivated a simple philosophy: sobriety as a life choice. “Sobriety,” he said, “to have more time to live according to what motivates you.”

In that house, which was both home and refuge, Pepe welcomed presidents and neighbors, farmers and onlookers, always with the same mate, the same patience and the same tenderness. Silvio arrived there, barely able to remove the dust from his journey, accompanied by his wife, flutist Niurka González, and his daughter, pianist Malva Rodríguez.

Lucía awaited them with her usual poise: sadness and laughter without compromise, the lucidity of someone who has loved and fought, the serenity of someone who knows that life goes on. She welcomed them into her small kitchen-dining room — the diminutive, in this case, is not a flirtatious term, but an exact description.

On the table, among books, bread, mate and notes, there was memory. A lot of memory. At that table, Lucía and Pepe spent long hours discussing politics, reading poems, listening to music or laughing. They also — as she herself says — had harsh disagreements. Like life itself.

It was a close and warm conversation between Lucía and her Cuban guests, a long after-dinner conversation, with Pepe still wandering around the house in the form of an anecdote, an idea, a refrain.

Silvio, Niurka, Malva and the three or four other people present listened to her without blinking. They spoke of Pepe’s legacy, of the need for new generations to “take up the flag” of the Latin American integration he dreamed of beyond governments.

Lucía recounted that until his last day, Pepe fulfilled his rituals. “Until the last day he could, he would ride the tractor,” she recalled. “Even if it was only for half an hour, he would go out and come back happy.” When he could no longer, he rode an electric tricycle; later, in a wheelchair. And yet, he continued teaching.

“He gave classes to the custodians — who were his colleagues, first and foremost — so they could learn how to hook up tools, drive the tractor, and care for the land. He would say: ‘If I leave, you can’t lose your jobs. We have to create jobs for you.’ Always sow, you understand? Sow.”

And during those difficult days, a song from Silvio arrived for Pepe and Lucía.

“Oh, did he get to listen to it?” Silvio asked, astonished.

Lucía nodded with a gentle smile. “Yes, he did. And he saw the video you sent.”

It was the Argentine singer-songwriter León Gieco who suggested that artists from around the world send messages to Pepe when it became known that his health was deteriorating. The farm was then flooded with music and affection, with voices and messages from the most remote corners — even Mongolia, Lucía says with a laugh. Among them was Silvio’s song: “Más porvenir” (More Future).

Before singing it in the video, the singer-songwriter said:

“Dear Pepe, this is my greeting from Cuba to you and Lucía. I began these verses in 2009, when I heard you say some things, and I finished them a few days ago, motivated by the call of our beloved León Gieco. A big hug.”

From those conversations with Pepe and Lucía — and from so many others he heard — emerged the song that Silvio performs today at every concert on his Latin American tour.

At one point, the conversation naturally turned to culture as a powerful tool for transformation. Lucía spoke of the “murgas” — “the sung resistance, year after year” — of Galeano, Benedetti, Zitarrosa and Daniel Viglietti.

She recalled when her grandmother took her as a child to the Solís Theater, back in the 1940s, to see a very young Alicia Alonso dance Swan Lake with the New York Ballet Theatre: “She told us: ‘Look closely, she’s the best in the world.’ I’ve never forgotten it.”

She also evoked a nurse from Pinar del Río who cared for her other grandmother and spoke to them about Cuba and Martí during the long nights on call. And she declared herself an admirer of Alejo Carpentier: “He brings out the Spanish language like few others.”

The singer-songwriter reciprocated with gifts: a book and his latest albums. “If you don’t listen to that music, give it to whoever you want.” Lucía laughed: “Of course not! I’ve always listened to you. First I listened to Carlos Puebla; then, to you, the New Song Movement. You’ve always made it here.”

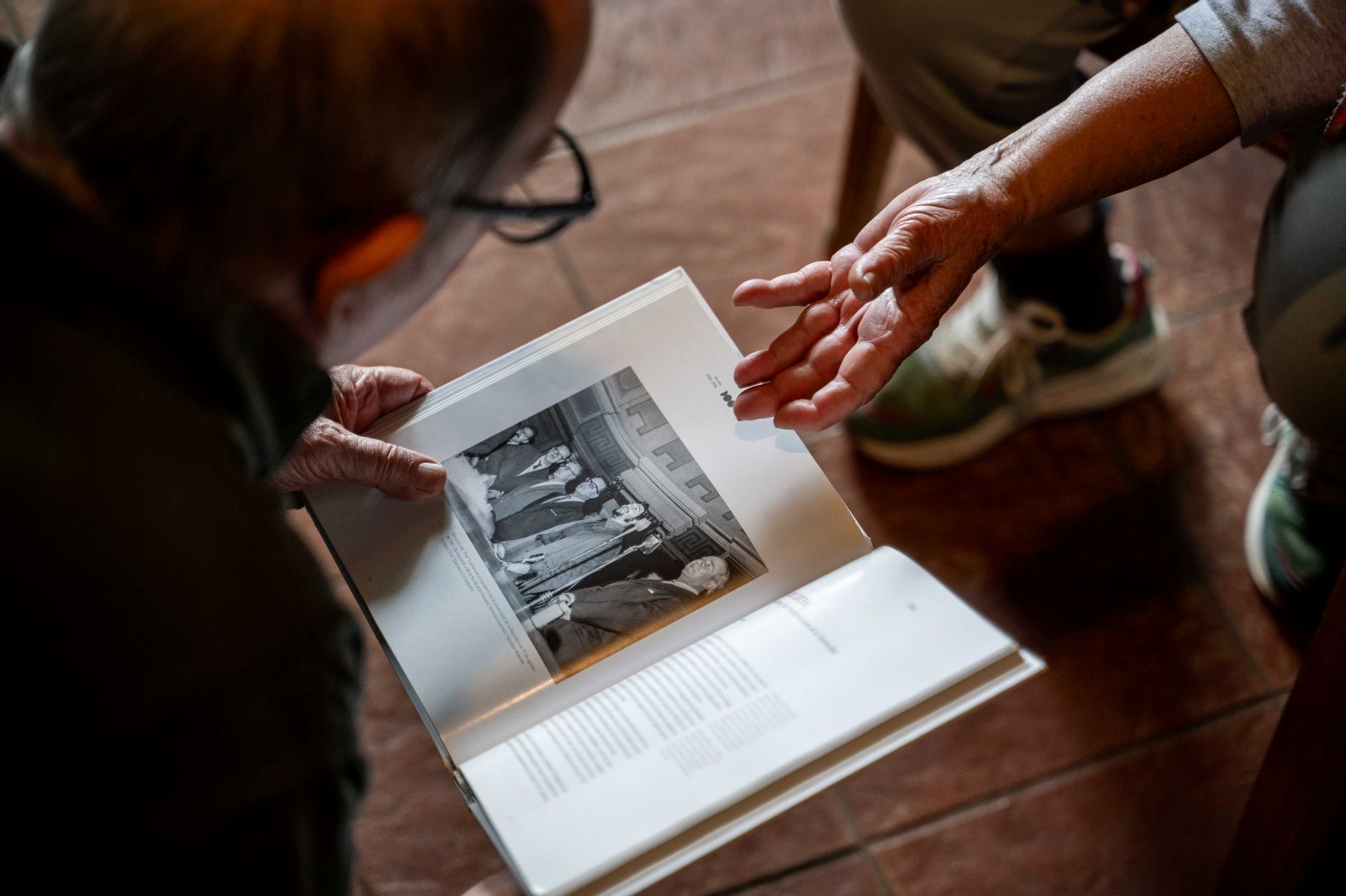

There was also a shared geography. Lucía showed a little-known photo: Che in the University Auditorium, in 1961, presented by a then-Chilean senator named Salvador Allende. Stories intersect and today seem written in indelible ink.

Between topics, the future loomed like a beacon. “We must connect universities, create regional brigades to deal with fires or earthquakes, share organ banks, coordinate medicine purchases. It can’t be that during the pandemic we haven’t produced vaccines together. That can’t happen again.”

Pepe always said it: don’t stop campaigning, don’t back down, talk to the people. “No one can replace one-on-one,” he repeated. That’s why, together with Lucía, they conceived the neighborhood mate days: unfiltered gatherings to listen and discuss. From there — they both believed — true leadership is born, the kind that ensures projects don’t get cut short.

It was an unparalleled privilege to have witnessed that meeting and listened, for over an hour, to a woman like Lucía: lucid, affectionate, indispensable.

Almost a decade ago, I saw them together in Havana. It was in 2016, on Santa Rosa Street, in the El Pilar neighborhood, during the 71st concert of the “Por los Barrios” tour. Pepe and Lucía arrived, and the neighborhood erupted in applause. Pepe extended his hand to shake, and a bouquet of hands — black, weathered, with worn nail polish, golden nails, hands of all colors — clasped his as if they never wanted to let go.

The next day, on his blog, Silvio wrote that Mujica had said that the concert had been a “perfect closing” to his visit to Cuba. And he recalled that Pepe had then shared with him a lesson from his teacher José Bergamín: “Poetry is telling things with other words, but not just any words.”

Perhaps that’s the key to “Más porvenir”: speaking to Pepe — and Lucía — with the words that belong to them, those of the future and the light in the midst of so much darkness.

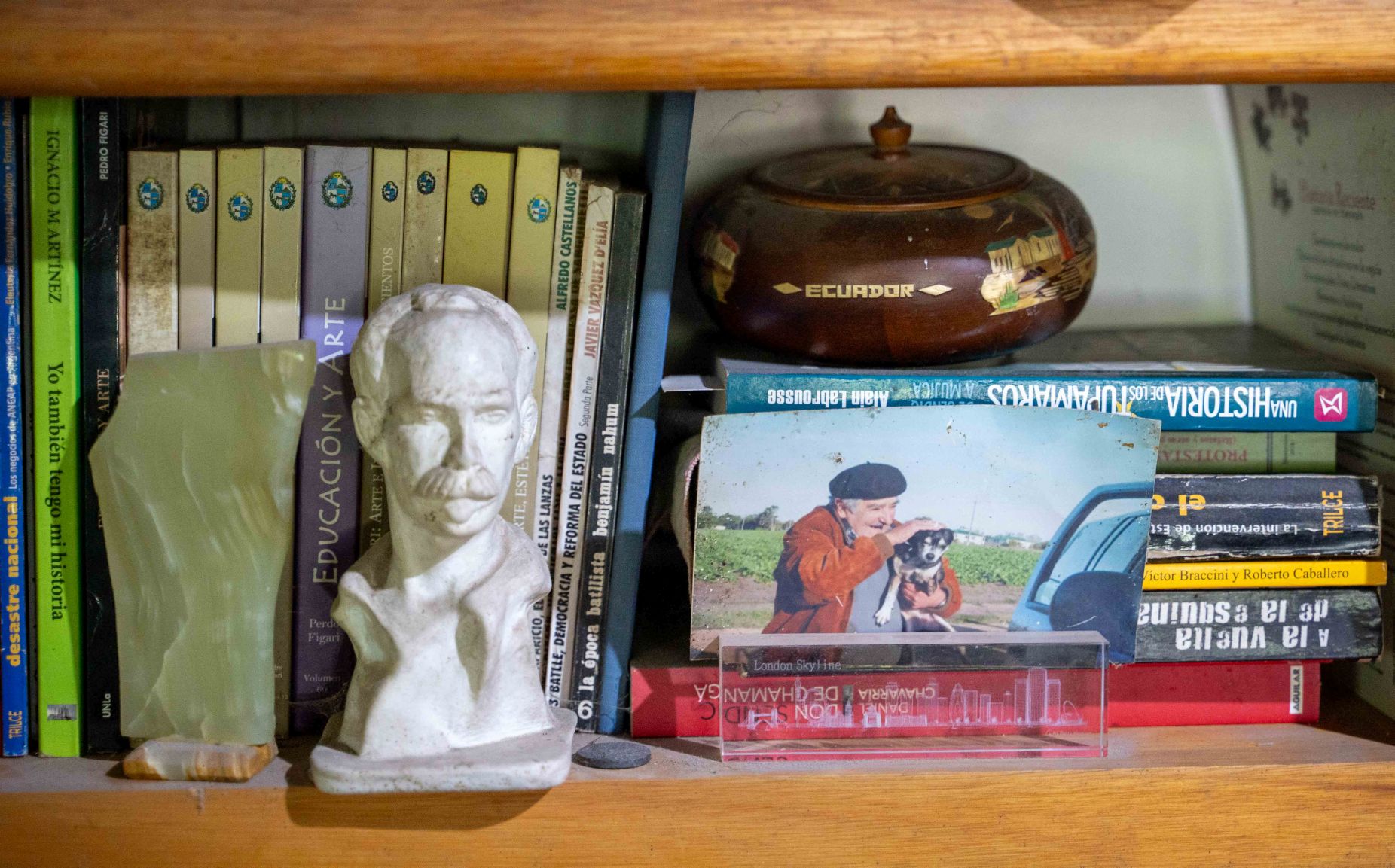

They said goodbye outside the house, under the clear sky of the outskirts. Lucía accompanied the visitors almost to the gate. Before that, she showed them the sequoia: the tree whose roots hold Pepe’s ashes, along with those of Manuela, his mixed-breed dog who was his shadow for twenty-two years.

“Pepe was a sower,” Silvio had said moments before.

Because Mujica, who lived so close to death from a young age, always thought about leaving everything ready. In 2020, he said it with his usual serenity: “My future destiny is under that sequoia, where Manuela is buried. When I die, they’re going to burn me and bury me there.” And so it was.

In that farm where so much was sown — ideas, affection, vegetables, a future — there remains the certainty that, even in absence, someone continues pushing from the middle of the squad. Because life, as the song says, was past, yes; but, definitely, there is always more future.

English-speaking readers interested in exploring the songs of Silvio Rodríguez can check out 50 of his songs, sung for the first time in English. Here’s the access to all 50 songs in YouTube:

https://cubansongbook.blogspot.com/2022/05/the-amazing-cuban-songbook-songs-by.html