From mid-May to August 26, the Visual Arts Development Center (CDAV,) in Old Havana, is hosting a unique exhibition. It is Marcas Registradas (Registered Trademarks), a graphic work by Arnulfo Espinosa (Havana, 1977) that moves in a hybrid territory between design and art. The exhibitor bases his work on universally recognized trademarks to reinterpret them, resignifying them, with large doses of Cuban wit, resorting to the norm of a common language among the inhabitants of the archipelago, their history, desires and daily frustrations. An exercise in lucid sharpness and, on occasions, warm empathy that uses the absurd, parody, sarcasm and irony to build a bridge between today’s Cubans and their circumstances. It is a work, let’s say it from the beginning, that appeals to the intelligence of both the sender and the receiver.

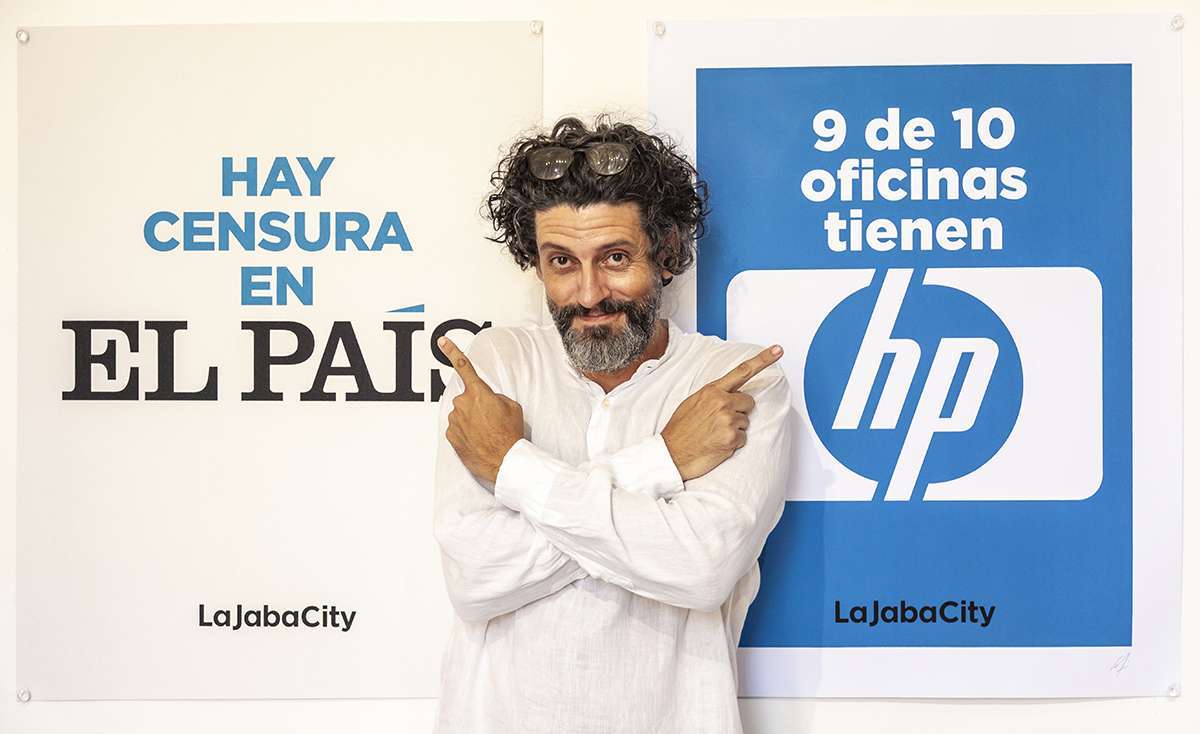

Arnulfo is a Graduate of Informational Design from the Higher Institute of Design (ISDI), promotion of 2001. On a professional level, he has specialized in the “development of graphic brands and visual identification systems,” he has taught at university level and ventured into fashion, conceptual art and jewelry design. In addition, he is the co-author of several titles on logos and brand typologies. But, above all, he has been known since 2016 for being the creator of LaJabaCity (TheBagCity), a kind of alter ego, a virtual site where they go to give their ingenuity, considered as memes by some, and quasi-conceptual works of art, by others.

Let’s start with the dialogue

Define LaJabaCity. Briefly tell us about its genesis, and how it has mutated in intentions, scope and language from 2016 to date.

It began as what it still is: a space for thought, except that I myself was not aware of this at the beginning. It began as the mouthpiece of reflections prior to the moment of creation. There was no intentional synchronization between thought and graphic production, there was no pre-established method for the work. I sat down to have fun graphing with an apparently innocent humor, but full of messages about everything that impacts me. The change, then, did not occur in the essence of that alter ego with a brand name; the change occurred in the method of realization and in the awareness of graphic creation as a process and need for personal expression, especially of what happens around me and moves me to think.

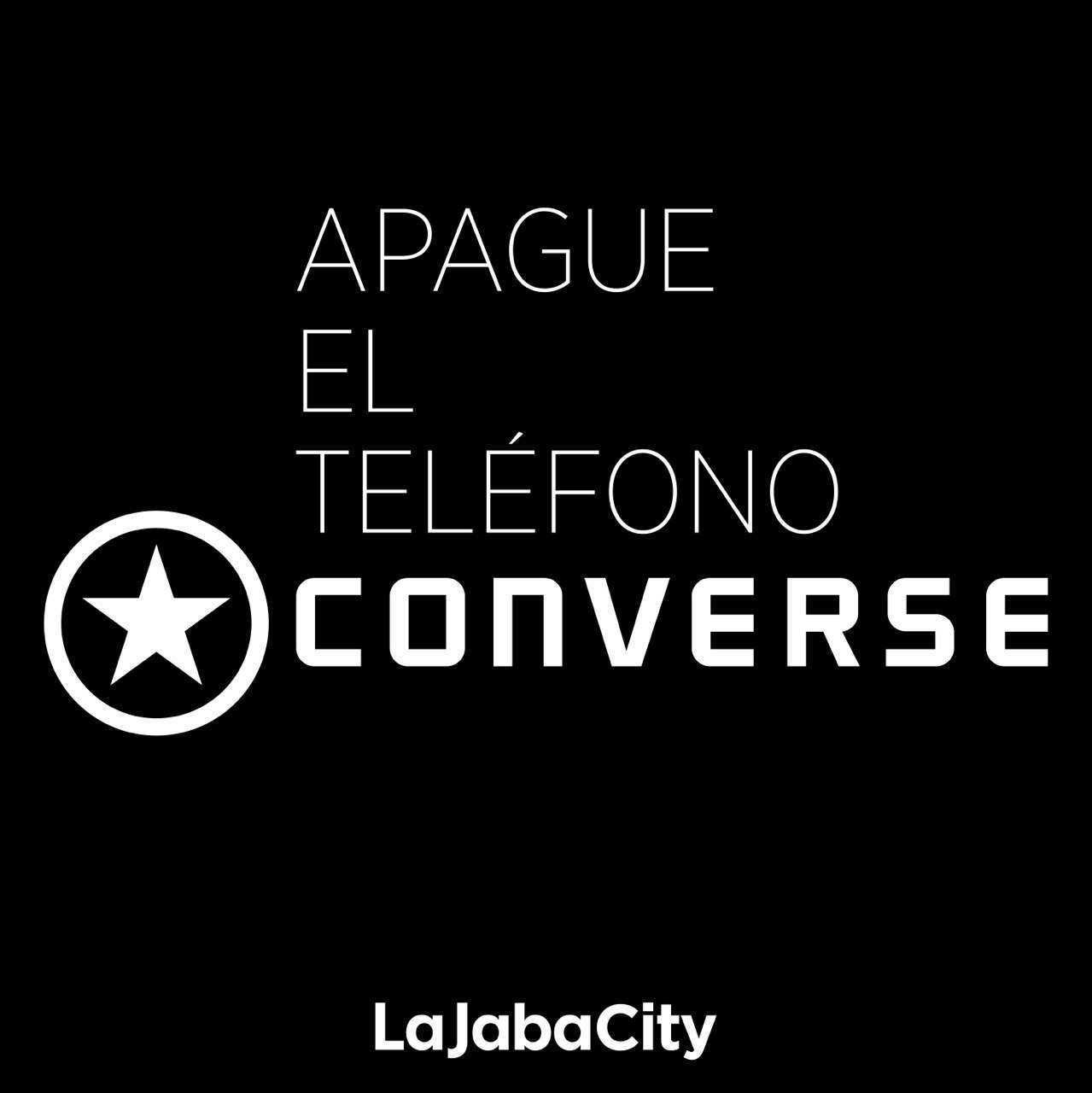

LaJabaCity is the chronicle of the Cuba that I had to live, in the register of the most popular language. It speaks in Cuban street language, in Spanglish, with double meanings, acidity and irony; essential ingredients of the humor that characterizes us as a people.

Your creative work around LaJabaCity is strongly related to the world of memes, which, as an expression of popular culture, is relatively recent. Do you fully register and recognize yourself in that aesthetic or is it, in your case, a mere starting point to achieve results of greater communicational and artistic scope?

It is not a meme site on social media, the meme is just one more aesthetic that has been used to convey its message, as is graphic design with its codes, genres, and tools. Hence, it has also participated in fashion shows printed on garments, that it has been printed in screen-printed poster format, and that it has collaborated with brands that want to be parodied from the conceptual prism of LaJaba (ROX 950, Rothmans, MSK Music, INAF Agroforestry Research Institute, Omaigá and MARABÚ).

As a designer, I have worked extensively on branding projects, or design of identification systems. I have had the opportunity to design brands from all sectors, activities and scales: companies, business groups, ministries, campaigns, events, musical groups, cultural institutions, record labels and publishers… I also had the great opportunity to co-author two books with Norberto Chaves, a veritable international design guru. These experiences constituted schools for me and were thought exercises that provided me with the conceptual elements to fully understand everything related to the brand and, in general, its creation processes based on design, hence the aesthetics of “the branding,” “the designed” — two concepts of popular culture — I find it spontaneous to express myself.

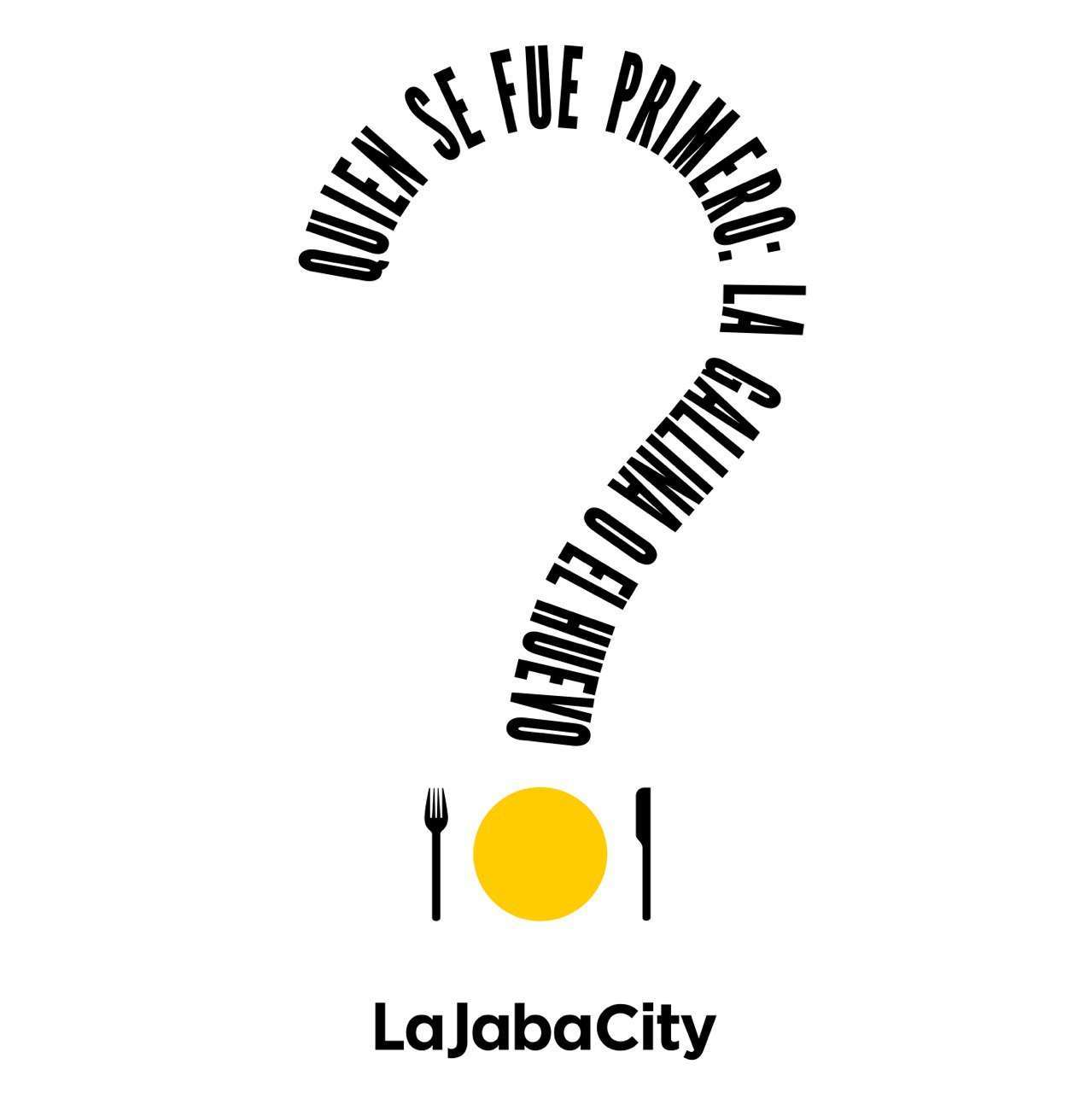

Marcas Registradas is made up of seven series. Namely: “Superpípol” (2017-2023), “Cuba USA LaJabaCity. Cuba abierta al mundo” (2016-2018), “Historieta” (2018-2023), “Marcas líderes cubanas” (2021-2022), “Mi primer Pala-Piña” (2022), “El mundo entre cuatro paredes” (2017-2023), “Preguntas sin respuestas” (2023) and “Coja la Cola” (2023). Can you briefly tell us what are the characteristics of each one?

The Marcas Registradas exhibition is my first personal exhibition dedicated to a work that belongs more to the field of artistic production than to design. Before that, I had also exhibited works from different areas of graphic design at the CDAV in an exhibition called Tipografiando. The current one is divided into 5 series, as you say. Both the sculpture (“Mi primer Pala-Piña”), as well as the super graphics and action (“Coja la Cola”) and the video animation are proof that there are no discursive borders to develop this space of thought. Each one constitutes the beginning of paths that will surely be traveled through new works. The idea of bringing these messages closer to the public is the backbone that articulates all the artistic production of this project. The street, more than the gallery, is its source of inspiration and its final destination.

The Cuban reality, as a thematic field taken up repeatedly, weaves a chronicle that grows over time. In this chronicle, there are realities that are being left behind and others that, on the contrary, widen their footprint and lengthen the validity of the message of the works.

The first series is now called Cuba USA LaJabaCity. It speaks of the encounter of international brands with our popular culture in the thaw era. It was a parody of the cultural phenomenon that was on the horizon. Historieta began with the COVID, the return to tensions between Cuba and the USA and the economic crisis that ensued. In it, a change in mood is noted, the humor becomes more caustic and reaches its peak in the series Marcas líderes cubanas. In the latter, our most aired expressions “become” brands of our register and find a top place in the sculpture Mi primer Pala-Piña, a wooden toy that ironizes about cultural formation through language and how through continued use the most risqué expressions are integrated into everyday language. Súper pípol is a tribute to the people, to Cubans taken to the scale of a superhero as they daily face problems that surpass them. El mundo entre cuatro paredes puts our own reality in perspective with that in which the world lives. The universal problem of the human being who lives in societies in crisis and their interaction with the different instances of power.

Caridad Blanco

During the development of this article, Arnulfo kept insisting that I not miss talking to Caridad Blanco de la Cruz, who is the curator of Marcas Registradas. And that is what I did.

Caridad, without a doubt the work of Arnulfo Espinosa has a strong satirical and parodic component. Not a few people believe that the so-called “high culture” cannot allow itself this “lightness.” What would you say to those who think like this?

In the first place, it would be necessary to distinguish that this is based on a prejudiced belief. Then, it is necessary to emphasize that humor is not synonymous with lightness. Humor is a cognitive and emotional capacity to perceive reality, which has, in addition to a social dimension, a critical perspective. It is even considered an aesthetic category and, specifically, it is expressed in different ways; forms that in many cases are juxtaposed or converge: irony, absurd, satire, farce, parody, sarcasm, simulation, cynicism, obscenity, grotesque and pastiche. Travestying can also be understood as a tool at its service, and its role in the complexity of carnival can also be appreciated.

It would be inconsistent to label light masterpieces such as: the series of engravings Los Caprichos, by Francisco de Goya; El jardín de las delicias, by El Bosco, or the novels Don Quixote de la Mancha, by Miguel de Cervantes, and Las cartas persas, by Montesquieu, due to the presence and prominence of humor in them.

Likewise, it would be untenable to do so with respect to Cuban art, in the face of characters like El Bobo by Abela, Salomón, the philosophical comic strip of Santiago Armada (Chago); the novel Tres tristes tigres, by Cabrera Infante, or films such as La muerte de un burócrata, by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and La vida es silbar, by Fernando Pérez. A judgment like the one that gave rise to your question breaks down when examining the tradition, the ancestry and value enhancement of humor in the visual arts, and much more so when faced with the discourses of a group of paradigmatic artists since the 1960s, and to this day, who have expanded the presence of humor, which is part of a cultural phenomenon of great wealth, impossible to cover here.

Believing that humor weakens or makes art inconsistent is discriminatory and a sign of ignorance of its true essence, which, according to Bakhtin, is a reflection and understanding of the permanent “imperfection” of the world. A world that humor dissects with its own logic of “explorer of the unexpected,” a metaphorical expression with which N. Dimitrieva defined it at the end of her essay El papel heurístico del humor.

Again with Arnulfo

You are trained as a designer, which is an activity that combines technical prowess with artistic skills. At this point in your work, do you consider yourself more of an artist than a designer? Can both activities be separated in you? Where is your work going?

As a designer, I have had a practically non-stop job since I started my professional life. LaJabaCity, however, arose spontaneously and without intending to, it became the beginning of my work as my own work, as a space for self-expression. Both are areas that are not excluded or canceled out since they feed on each other. LaJabaCity’s work develops a particular path that explores formats and new means of expression, and over time solidifies its poetics. My work as a designer enriches it with graphic experiences while incorporating much of LaJaba’s creative freedom and humor, as long as it is related to the design project at hand. Let’s say that it promotes in me “that state of play” that the renowned designer Paula Scher speaks of.

Personally, LaJabaCity is a way to expand my inner world beyond the physical space I occupy. It is a work that raises questions, concerns, longings, outbursts, dilemmas, anguish, joy, shows my demons and angels, and gives me full freedom of creation and expression.

And again, Caridad

It is a Byzantine effort to try to establish the limits of art, what is intrinsic to this human activity and what would not fit in any way under that category. Even so, it occurs to me to ask you if Marcas Registadas can be classified, with all rights, as an exhibition of visual art and not as a simple collection of memes.

First, it must be said that it is possible to make an exhibition of visual arts based on memes, and not just memes, but even many other things, even if these things are not considered art or are not definitely art.

I was aware from the start that the LaJabaCity material could only be perceived as a meme. However, the ideas that Arnulfo Espinosa exposes with the messages of his alter ego go beyond that designation. “Preguntas sin respuestas,” a video work within Marcas Registradas, plays with the question: What is LaJabaCity? and launches other many questions on what it can be (or not) in addition, and leaves to defenselessness those who need to pigeonhole, set limits to creation, to its understanding, to the senses that open up before expressions like this (and even others).

Beyond reiterating that LaJabaCity is that space for thought that I discovered during the pandemic — something that has been maintained and can be corroborated by inventorying and analyzing its abundant “messaging” —, it is not in my interest to try to constrain it, delimit it, or set definitions or ways of interpreting it that enhance it in the eyes of the readers and those who value it. It would be like betraying what Arnulfo and I jointly subscribe to with the video animation Preguntas sin respuestas, and with the exhibition in its entirety, which is also a text to be read; that of the curatorship itself (in the verifiable and in the undiscovered), and that is not reduced to the brief words printed on the brochure that accompanies the exhibition.

In those writings: the one on Arnulfo’s works (posters, sculptural toy, video animation and super graphics) and the undersigned for the staging of LaJabaCity that is Marcas Registradas, there are grounds that make the sample classify within what you call an exhibition of visual art, although there are those who may think otherwise.

What was your biggest challenge as a curator when facing the elaboration of an intelligible and attractive discourse based on the pieces of Arnulfo Espinosa?

Looking back on the entire process, I had several challenges. First, to discern within more than 400 works — the result of 7 years of work by Arnulfo — which were some of the most meritorious regularities that this phenomenon had and was necessary to show. Also, what works deserved to be among the 60 that finally made up the exhibition. On the other hand, building an exhibition that would take LaJabaCity to a higher level, take it out of its comfort zones, at the same time as conceiving an exhibition that would transcend its usual way of discoursing on the social media (Instagram, Facebook) and that would not look like what was previously done around it. This, together with the need to achieve a selection (and a conceptualization) that would show the richness of this type of work, new possibilities of expression that I envisioned for it, and arguments to demonstrate how these messages, born in the field of graphic design with LaJabaCity, expand and enrich our tradition of humor.

In Marcas Registradas multiple stories converge. Braiding the different levels of narrative that exist in it was challenging in more ways than one, but it was undoubtedly an enriching exercise as a whole and also fun, as is the case with humor, which is no less serious, challenging and liberating.

I close with Arnulfo

Humor, that expression that demands, at the same time, mental speed and self-recognition capacity, has been pointed out as one of the identity signs of what is Cuban. The appearance of this resource occurs in you spontaneously or is it a self-imposed communication strategy?

Making jokes, that intrinsically Cuban way of being, is a balance rod in the face of the instability we inhabit. A rod that also serves to measure things. Since it is sharp at the ends, it is also a spear. We talk with humor about serious topics to understand them deeply and, finally, we mark the intellectual discovery with the sign of a complicit smile. When Ochún, a Yoruba deity who syncretizes with Our Lady of Charity, patron saint of Cuba, laughs out loud, it means she is angry.